By Sam Noir

December 18, 2013

Toronto

Something significant and radical has occurred in the Georgia Ridley Salon at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Original comics artwork has steadily gained acceptance within the hallowed institutions of mainstream galleries and museums, but never in as bold a curatorial manner as this.

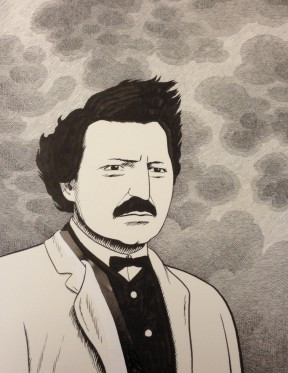

A stark black and white, inked, portrait of Louis Riel sticks out like a sore thumb. Surrounded by stacks of period specific, painted, (colour) artwork, in a setting that recreates the viewing context of a period spanning Canadian Confederation and the First World War.

A portrait of Riel would never have found its way into any English Canada salon of that time. A crusader for Métis rights, and charismatic leader of the 1869-1870 “Red River Rebellion”, Riel was branded a “traitor” by the federal government, and viewed as such in the province of Ontario, and particularly the city Toronto. How fitting then, that he should end up here of all places, today.

This decidedly contemporary juxtaposition provokes conversation, and challenges our traditional narrative as Canadians. The portrait incidentally, is the original cover art for the tenth anniversary edition of Chester Brown’s graphic novel Louis Riel: A Comic Strip Biography.

Riel remains controversial figure, and difficult to place within Canadian history. He’s a powerful symbol of Native and French Canadian rebellion against centralized English-speaking government powers. However, we now live in a society where Multiculturalism is espoused, and Bilingualism is national policy. Chester Brown’s graphic biography is a reflection of this current cultural paradigm, particularly since Riel is now viewed as a “Father of Manitoba”, in spite of his defeats. It is notable that the Canada Council, a government run funding agency for the arts, provided support to Brown in the creation of this work.

Tucked away in a small alcove in a corner of the salon, original artwork from Chester Brown’s Louis Riel graphic novel is displayed, revealing Brown’s process. Each frame showcases what are essentially small individual panels of the same dimensions, on separate small pieces of paper, a half dozen of each which were eventually grouped together to form a “page” of artwork. Imagine each of these panels to be a frame of film. In film editing terms, this allowed Brown the ability to “non linear edit” as he crafts the story… adding or deleting panels and moments from any point in the chosen narrative as he goes along creating the work as a whole.

We also need to note that Brown calls his biography a comic strip. Drawing from a more traditionally populist format, and defining itself away from the more literary pretentious term, graphic novel or even the more common place name of comic book. Both terms which come with a degree of cultural baggage in the current landscape.

During the process of creating this work, Brown adapted a large stylistic influence from cartoonist Harold Gray, the creator of the comic strip Little Orphan Annie. In fact, there are examples out there showing how Brown redrew panels he created earlier in the process to keep this aesthetic choice consistent. The choice of Gray is interesting in that Gray is largely considered a political artist himself during a tumultuous period of American history. Recall that the original Little Orphan Annie cartoon strip was a politically charged reaction to the changing times of the depression-era nineteen thirties – a fact largely forgotten in the shadow of the Broadway musical and cinematic adaptation that has taken popular root in its cultural stead.

Gray could originally be defined as a Republican during the pre-Depression years at the start of Little Orphan Annie (most historians cite the name of his character “Daddy” Warbucks as a suggestion about where the character’s initial fortunes came from), but many argue that the views expressed by his characters in later years were libertarian in nature. Brown became politicized during the creation of Louis Riel, and has run as a candidate for the Libertarian Party of Canada in the riding of Trinity-Spadina since the 2008 federal election.

The spine of Brown’s Louis Riel rests on the side of democratic process, with the elected leadership of the largely mixed francophone/aboriginal Red River Settlement majority (Métis), battling against the tyranny of an oppressive English Canada asserting its agenda and the machinations of The Hudson’s Bay Company, hoping to profit from this transfer of power and land rights. Though Riel’s methods and actions may not always be viewed sympathetically, you can understand his motivations of fairness. Particularly as the elected leader of the provisional government, negotiating its place in the developing country of Canada – and as an member of Canadian Parliament, elected multiple times, but never having sat in the House of Commons for fear of arrest.

Canada’s first Prime Minister John A. Macdonald is not painted in a flattering light, and his decisions shown here have far reaching implications. A political creature, choosing the expediency of arms over the complications of keeping his promises to Riel and the provisional government of Manitoba; a far cry from the Father of Canadian Confederation we learned about in our history books. More devious still were his manipulations around the negotiations with the Métis in Saskatchewan to incite rebellion, and justify the mounting expenses in construction of the Canadian Pacific railroad across Canada, by sending in troops.

Whereas his sympathies undoubtedly lie with Riel and the Métis, in the story he’s chosen to tell, Brown has selected moments that highlight a certain degree of ironic, even dark, humour to Riel’s story. Reminding us that this book is designed to entertain as much as it is to inform. Far from being a comprehensive volume on the life of Riel, Brown’s selection of vignettes within the allotted pages is equally fascinating.

Brown’s exploration of Riel’s years following Red River, institutionalized and gripped by “Divine Madness” is not surprising to those familiar with his earlier autobiographical work. Where his mother’s schizophrenia was not overtly stated, but often a strong subtext in the depiction Brown’s developing years. These visions and religious fervour haunt Riel, and follow him through the Métis uprising in Saskatchewan, leading up to his surrender to the Canadian authorities, and to the end of his life. The closing chapter, leading us to the final moments of Riel’s execution, depicts the courtroom where the question of his sanity is laid before those who knew and encountered him.

In some parts of the chronology, the narrative jumps years at a time, quickly through different characters and settings between panels on the same page. However, when Brown chooses to slow down the pace, utilizing what has commonly become known as “decompressed storytelling”, the quiet results are compelling and moving. Individual “moments” paced out in panels of the same size, six to a page stretching across multiple pages. Similar to Watchmen, which functioned similarly using a nine panel per page grid structure. With no variation in size and placement of panels, the panels become a singular viewing portal… a “window” into the world of Louis Riel.

The final sequence in Part One of the story, depicting Louis Riel alone in Fort Garry, and then leaving the Red River Settlement, stretches across a luxurious four pages. Dwelling on mundane, yet affecting moments of Riel rising from bed and eating a solitary meal, before being warned of the English troops descending upon him. Unlike the end of a traditional American cowboy movie, in this Canadian “Western”, Riel does not head triumphantly into the horizon and the sunset, but towards the reader, who is looking down above him as he walks in the rain.

You can view these particular pages of original art for yourself, showcased in the salon’s alcove at the Art Gallery of Ontario until September 2014.

Honours bestowed on Louis Riel: A Comic Strip Biography include 2 Harvey Awards, and its placement as a semifinalist in CBC’s prestigious Canada Reads program. It was the first Canadian Graphic Novel to become a best-seller, and on its heels has spawned a renaissance in the genre of graphic novel/comic book biography and similar non fiction illustrated work.

During an earlier regeneration, the author of this article found himself living as an academic. He held three degrees from Queen’s University in Fine Art, Art History and Film Studies in a death-like vice grip, describing himself at the time as an Installation Artist, Pop Culture Junkie and Film Maker.

Sam Noir is currently a rabble rouser, and maker of comix and toys. He claims Toronto, Canada–the most culturally diverse city on the whole damn planet–as his home.

Our first set of reading material for the week is a collection of work by comics creator Terry Moore: Strangers in Paradise, Vols I and II; and Rachel Rising.

Our first set of reading material for the week is a collection of work by comics creator Terry Moore: Strangers in Paradise, Vols I and II; and Rachel Rising.