Amobarbital

|

|

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

|

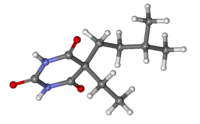

5-ethyl-5-(3-methylbutyl)-1,3-diazinane-2,4,6-trione

|

|

| Clinical data | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

Oral, IM, IV, Rectal |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ? |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Biological half-life | 8–42 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 57-43-2 |

| ATC code | N05CA02 (WHO) |

| PubChem | CID 2164 |

| DrugBank | DB01351 |

| ChemSpider | 2079 |

| UNII | GWH6IJ239E |

| KEGG | D00555 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:2673 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL267894 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C11H18N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 226.272 |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

|

|

|

|

| (verify) | |

Amobarbital (formerly known as amylobarbitone or sodium amytal) is a drug that is a barbiturate derivative. It has sedative-hypnotic properties. It is a white crystalline powder with no odor and a slightly bitter taste. It was first synthesized in Germany in 1923. If amobarbital is taken for extended periods of time, physical and psychological dependence can develop. Amobarbital withdrawal mimics delirium tremens and may be life-threatening.

Contents

Pharmacology[edit]

In an in vitro study in rat thalamic slices amobarbital worked by activating GABAA receptors, which decreased input resistance, depressed burst and tonic firing, especially in ventrobasal and intralaminar neurons, while at the same time increasing burst duration and mean conductance at individual chloride channels; this increased both the amplitude and decay time of inhibitory postsynaptic currents.[1]

Amobarbital has been used in a study to inhibit mitochondrial electron transport in the rat heart.[2]

A 1988 study found that amobarbital increases benzodiazepine receptor binding in vivo with less potency than secobarbital and pentobarbital (in descending order), but greater than phenobarbital and barbital (in descending order).[3] (Secobarbital > pentobarbital > amobarbital > phenobarbital > barbital)

It has an LD50 in mice of 212 mg/kg s.c.[citation needed]

Metabolism[edit]

Amobarbital undergoes both hydroxylation to form 3'-hydroxyamobarbital,[4] and N-glucosidation[5] to form 1-(beta-D-glucopyranosyl)amobarbital.[6]

Indications[edit]

Approved[edit]

Unapproved/off-label[edit]

When given slowly by an intravenous route, sodium amobarbital has a reputation for acting as a so-called truth serum. Under the influence, a person will divulge information that under normal circumstances they would block. As such, the drug was first employed clinically by Dr. William Bleckwenn at the University of Wisconsin to circumvent inhibitions in psychiatric patients.[7] The use of amobarbital as a truth serum has lost credibility due to the discovery that a subject can be coerced into having a "false memory" of the event.[8]

The drug may be used intravenously to interview patients with catatonic mutism, sometimes combined with caffeine to prevent sleep.[9]

It was used by the United States armed forces during World War II in an attempt to treat shell shock and return soldiers to the front-line duties.[10] This use has since been discontinued as the powerful sedation, cognitive impairment, and dis-coordination induced by the drug greatly reduced soldiers' usefulness in the field.

Contraindications[edit]

The following drugs should be avoided when taking amobarbital:

- Antiarrhythmics, such as verapamil and digoxin

- Antiepileptics, such as phenobarbital or carbamazepine

- Antihistamines, such as doxylamine and clemastine

- Antihypertensives, such as atenolol and propranolol

- Alcohol[citation needed]

- Benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, clonazepam or nitrazepam

- Chloramphenicol

- Chlorpromazine

- Cyclophosphamide

- Ciclosporin

- Digitoxin

- Doxorubicin

- Doxycycline

- Methoxyflurane

- Metronidazole

- Narcotic analgesics, such as morphine and oxycodone

- Quinine

- Steroids, such as prednisone and cortisone

- Theophylline

- Warfarin

Interactions[edit]

Amobarbital has been known to decrease the effects of hormonal birth control, sometimes to the point of uselessness.[citation needed] Being chemically related to phenobarbital, it might also do the same thing to digitoxin, a cardiac glycoside.[citation needed]

Overdose[edit]

Some side effects of overdose include confusion (severe); decrease in or loss of reflexes; drowsiness (severe); fever; irritability (continuing); low body temperature; poor judgment; shortness of breath or slow or troubled breathing; slow heartbeat; slurred speech; staggering; trouble in sleeping; unusual movements of the eyes; weakness (severe).

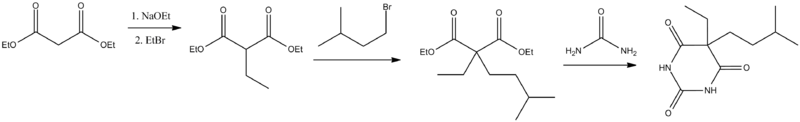

Chemistry[edit]

Amobarbital (5-ethyl-5-isoamylbarbituric acid), like all barbiturates, is synthesized by reacting malonic acid derivatives with urea derivatives. In particular, in order to make amobarbital, α-ethyl-α-isoamylmalonic ester is reacted with urea (in the presence of sodium ethoxide).[11][12]

Society and culture[edit]

It has been used to convict alleged murderers such as Andres English-Howard, who strangled his girlfriend to death but claimed innocence. He was surreptitiously administered the drug by his lawyer, and under the influence of it he revealed why he strangled her and under what circumstances. A year later he confessed on the witness stand and was convicted on the basis of these statements. He later committed suicide in his cell.[13]

On the night of August 28, 1951, Robert Walker's housekeeper found the actor in an emotional state. She called Walker's psychiatrist who arrived and administered amobarbital for sedation. Walker was allegedly drinking prior to his emotional outburst, and it is believed the combination of amobarbital and alcohol resulted in a severe reaction. As a result, he passed out and stopped breathing, and all efforts to resuscitate him failed. Walker died at 32 years old.

Street names for Amobarbital include "blues", "blue angles", "blue birds", and "blue devils".[citation needed]

See also[edit]

References and end notes[edit]

- ^ Kim, H. -S.; Wan, X.; Mathers, D. A.; Puil, E. (2004). "Selective GABA-receptor actions of amobarbital on thalamic neurons". British Journal of Pharmacology. 143 (4): 485–494. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0705974. PMC 1575418

. PMID 15381635.

. PMID 15381635. - ^ Stewart, S.; Lesnefsky, E. J.; Chen, Q. (2009). "Reversible blockade of electron transport with amobarbital at the onset of reperfusion attenuates cardiac injury". Translational Research. 153 (5): 224–231. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2009.02.003. PMID 19375683.

- ^ Miller, L. G.; Deutsch, S. I.; Greenblatt, D. J.; Paul, S. M.; Shader, R. I. (1988). "Acute barbiturate administration increases benzodiazepine receptor binding in vivo". Psychopharmacology. 96 (3): 385–390. doi:10.1007/BF00216067. PMID 2906155.

- ^ Maynert, E. W. (1965). "The alcoholic metabolites of pentobarbital and amobarbital in man". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 150 (1): 118–121. PMID 5855308.

- ^ Tang, B. K.; Kalow, W.; Grey, A. A. (1978). "Amobarbital metabolism in man: N-glucoside formation". Research communications in chemical pathology and pharmacology. 21 (1): 45–53. PMID 684279.

- ^ Soine, P. J.; Soine, W. H. (1987). "High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of the diastereomers of 1-(beta-D-glucopyranosyl)amobarbital in urine". Journal of Chromatography. 422: 309–314. doi:10.1016/0378-4347(87)80468-1. PMID 3437019.

- ^ Bleckwenn, W. J. (1930). "Sodium amytal in certain nervous and mental conditions". Wisconsin Medical Journal. 29: 693–696.

- ^ Stocks, J. T. (1998). "Recovered memory therapy: A dubious practice technique". Social work. 43 (5): 423–436. doi:10.1093/sw/43.5.423. PMID 9739631.

- ^ McCall, W. V. (1992). "The addition of intravenous caffeine during an amobarbital interview". Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience : JPN. 17 (5): 195–197. PMC 1188455

. PMID 1489761.

. PMID 1489761. - ^ "Use of sodium amytal during WWII". Battle of the Bulge - program transcript. PBS.

Ben Kimmelman, Captain, 28th Infantry: The assumptions were that this would have some kind of cathartic effect, the sodium amytal, which the men called blue 88's. You know, the most effective artillery piece of the Germans was the 88 and this was blue 88s, because the sodium amytal was a blue tablet.

- ^ GB patent 191008, Layraud, E., "The manufacture of unsymmetrical c.c.-dialkylbarbituric acids", issued 1923-10-25

- ^ US patent 1856792, Shonle, H. A., "Anhydrous alkali salts of 5,5-di-aliphatic-substituted barbituric acids and processes of producing them", issued 1932-05-03

- ^ Rebecca Leung (February 11, 2009). "Truth Serum: A Possible Weapon". 60 Minutes. CBS News.