The Age of Aquarius: An Urbanist Battle in Brazil

Aquarius, the new film from Brazilian critic-turned-director Kleber Mendonça Filho, sells the battle for redevelopment of an apartment complex in Recife, Brazil as nothing less than a battle for the soul of a nation. To the film’s great credit, even the least interested in urbanism among us will buy it; bravura filmmaking is bravura filmmaking any way you slice it.

The Aquarius, the building that lends its name to the film’s title, is unassuming both inside and out—luxury Northern-Virginia tower block it ain’t—though it isn’t lacking for personality. Since walls can only talk in the figurative sense, we learn about the building’s history from Clara (Sonia Braga), a resident of the Aquarius of more than 30 years. At 65 Clara has experienced the broad sweep of life’s joys and sorrows under the the Aquarius’s roof: she’s celebrated with family both close and far, survived breast cancer, lost her husband to an early death, watched her children grow old and leave the nest, renovated the space into a home for the record collection she’s amassed through the years as a music critic and lover of culture.

Cosmetic changes notwithstanding, Clara’s apartment has held onto a certain character through the years. We see this no more beautifully or succinctly than in an early scene that transitions seamlessly from a 1980s flashback to the present day. With the camera fixed in one all-seeing corner of the room, an elongated cross fade slowly transforms a scene of a jubilant and crowded birthday party into one of Clara enjoying the fruits of solitude in her modestly refurbished 2016 pad, the same record playing on the turntable in one decade as in the next. People and furniture arrangements come and go, but the soulfulness Clara has striven to cultivate in her home persists across time.

All that Clara has labored for over the years is threatened by the arrival at her doorstep of a construction company seeking to demolish the Aquarius. The company, represented by its president and his obsequious grandson Diego (Humberto Carrão), say they’ll keep the memory of the old building alive by naming the new one, blandly, “The New Aquarius” in its honor. Clara makes short work of their insincerity by pointing out that until very recently the new development was to be christened, even more blandly, “The Atlantic Plaza Residence.” The developers sulk back into their corner of the ring for regrouping, and it’s at this point that we realize we’ve been dropped into this boxing match in medias res. Clara has been stubbornly opposing the developers for at least six years, the building’s other tenants having long ago sold their apartments to the company and moved out.

Thus what could have been a treacly paean to preservationism is anything but. Our sympathy for Clara can only extend so far: every year Clara refuses to move out is another year her less-financially-stable former neighbors are kept from the money they’ve been promised for selling their homes. If Clara’s stubbornness were just a product of elderly nostalgia, it would be easier to dismiss her position. Instead, it’s the result of a deep-seated memory of history. The Aquarius is a receptacle for ugly memories as well as beautiful ones, and the former can be just as meaningful to Clara as the latter.

This could have been a point easily and glibly made in on-the-nose dialogue; instead it’s an occasion for Aquarius’s skilled director to play with genre to achieve the same ends. While the film starts, in 1980, as as a dreamily nostalgic period piece, it metamorphoses into a family melodrama, a raunchy bad-neighbor comedy, and, finally and most memorably, a haunted house film. This might leave some viewers reeling with narrative whiplash, but these changes in register nevertheless help us experience, both viscerally and in a condensed timeframe, what Clara has spent her whole life living.

Clara defends her home through thick and thin, not in spite of all the hurt that has transpired there, but because of it. It’s no surprise to find that same sense of commitment missing from all the younger people around her. In one heated debate with her daughter, Clara incisively calls an entire generation out for its dishonest reverence for the past. “When you love something, it’s vintage,” she snipes, “and when you don’t, it’s old.”

Clara’s not just speaking for the Aquarius here. It will escape precisely no one who sees this film that characters like Clara—strong, sexy, complicated, and well over the eligibility age for AARP membership—never get to be the stars of movies anymore. Cinema’s loss is likewise a loss for an entire generation of younger moviegoers. Sonia Braga hasn’t been called upon for a major film role in several decades, and Aquarius is as grand a rebirth from the ashes of cinema’s dustbin as any older actress could hope for. Braga positively lights the screen on fire, at times with the warmth of a candle yet at others with the violence of an erupting volcano. This is what it means to be a movie star, the type we like to sullenly say they don’t make like they used to anymore.

Clara’s conflict with the developers naturally comes to a head with Diego in a classic clash between the old guard and the new. While Clara is fully a product of Brazil, its buildings, and its institutions, Diego’s character formation has been outsourced to the world of elite, coastal business schools in the United States. Diego speaks that perversely charming language of ruthless appeasement and bottom lines. When Diego accuses Clara of lacking manners and asks her to show some respect for her former neighbors, she viciously turns the tables on him. “You have no character,” she erupts at him, “or, you do, but your character is money. It’s the rich, elite people like you who lack manners; you have no human decency.” Her polemic escalates until it threatens to melt right through the screen. When she eventually backs off just enough to let her opponent get a word in edgewise, that word is “meritocracy”. Cue the groaning and eye-rolling.

Diego’s limp appeal to his hard work and dubious life of hardships doesn’t win any converts to his side. Certainly not Clara, who’s ready to go down fighting in this battle-in-microcosm for the soul of Brazil against the forces of corporate greed and government corruption. In its final twenty minutes Aquarius pulls out all the stops, culminating in one of the most riveting conclusions you could hope to see at the movies this or any year. The very final scene, which sees Clara launching a metaphorical grenade right into enemy territory, doesn’t offer the kind of closure we’ve been conditioned to expect from other movies. Then again, most other movies aren’t as aware of the high stakes of their real-life antecedents as this one is.

Tim Markatos is an editorial fellow at The American Conservative.

Why Ballparks Can’t Save Cities

Baseball is a game of inches, but it is also a game of nostalgia. When Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore opened in the 1992 season it set off a wave of retro ballpark construction in the Major Leagues. The multipurpose “cookie-cutter” parks with their huge outfields and artificial turf (so they could be used for football in the offseason), with names like Veterans Stadium and Memorial Stadium, were obsolete and out of fashion overnight. As a result, after Fenway Park (1912) and Wrigley Field (1914), the oldest ballpark in the Major Leagues is Dodger Stadium, which opened in 1962.

The retro parks are built only for baseball, on real grass, and use many of the materials and strange configurations of the old parks, such as exposed brick and jutting corners for weird bounces, like AT&T Park’s “Triples Alley”. The New York Mets’ new home, Citi Field, even recreated part of the facade of long vanished Ebbetts Field for its Jackie Robinson Rotunda.

A traditional ballpark has a personality of its own and, occasionally, its owner. When Bill Veeck owned the Cleveland Indians in the 1940s, he altered Municipal Stadium’s dimensions regularly to favor the Tribe. Braves Field in Boston was built with a huge outfield in order to increase the number of triples hit.

Baseball teams and their parks also end up reflecting their cities—after all, the reason old ballparks like Fenway have their quirks is because they were built to fit in city blocks and Boston has some strange streets. In a similar way, several writers believe that Babe Ruth was sold to the Yankees as much because he couldn’t stomach Boston’s puritanical culture as Red Sox owner Harry Frazee’s money troubles.

Baseball has also brought cities together in a way not often seen in other sports. The 1968 Detroit Tigers were credited with calming the city after the race riot in 1967 and the unrest following the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr and Robert F. Kennedy. The ’77 Yankees and 2013 Red Sox are similarly credited with bringing their cities together at difficult times. The strong emotional bond between a city and a team feed into a city’s sense of place.

Last year Rod Dreher visited Siena and wrote about how within the walls each contrade, or ward, competes with every other one in the annual Palio horse race. They all have their own hymns, yet all are set to the same tune, the same one for the whole city when competing with other cities. A similar thing happens with baseball teams—it becomes the city versus all comers instead of one faction among many. Things might be said to go from “my city” to “Our bleeping city”.

But all is not as it seems.

Baseball stadiums are expensive to build and urban property prices have always been high, especially considering the amount of parking needed to accommodate 40,000 people. As a result, teams want public financing, tax abatements, and all the other ills that crony capitalism promotes. Paid for with higher taxes, increased public indebtedness, and highway improvements, the retro ballparks were sold to city, county, and state governments as a form of economic development and urban regeneration.

None of that has happened. Not even with Oriole Park at Camden Yards, which started the whole thing and cost taxpayers $282 million, according to Field of Schemes. According to Bloomberg in 2013, sports stadiums don’t fulfill development goals because they’re empty much of the time, the jobs they create are low-wage, and they divert spending on food and beverages from other businesses. In Baltimore, says Field of Schemes, the number of employers in the area fell between 1998 and 2013, while crime and unemployment were up.

Tim Chapin, an urban planning professor at Florida State University, told Bloomberg that Camden Yards had not saved downtown Baltimore or improved the poorer neighborhoods near downtown. Former Maryland legislator Julian Lapides said that the whole area was vacant on game days. “It’s a big hole in the center of the City.”

In that respect, stadium deals are no better than ordinary economic development funds. Back in December of 2012, the New York Times found that states and cities spend up to $80 billion a year on economic development incentives with nothing much to show for it in the way of stronger economies or more and better paying jobs.

The area around Camden Yards, however, is still better than some retro parks, such as Citi Field or Philadelphia’s Citizens Bank Park, which are entirely surrounded by parking. The real appeal of old ballparks (like Fenway and Wrigley) and the nostalgia for lost ones (like Ebbetts Field, Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, and others) comes from their history—many former ballparks have the location of home plate marked with a plaque, and Pirates fans still gather at the site of Forbes Field on the anniversary of Bill Mazerowski’s World Series-winning home run against the Yankees—and the way they were part of a neighborhood.

The area around Boston’s Fenway Park has seen a lot of changes come and go, but in addition to the new glass and steel luxury towers going up on Brookline Avenue, there are old warehouses (long-since converted into memorabilia stores and sports bars) and apartment buildings of similar age, their flaking brick facades and sagging wood floors belying their high rents. In Chicago, Wrigley Field gave its name to its neighborhood, Wrigleyville, which is still somewhat affordable and where people in neighboring houses can watch the game from their roofs.

Fenway and Wrigley prove two things: that neighborhoods can develop around ballparks, so long as the neighborhood isn’t torn down for parking and teams don’t need new ballparks every 30 years. But as long as team owners use threats to move a beloved team as emotional blackmail against an entire city—and public officials think can win votes on bad deals—sports franchises will continue to feast on public funds like a slugger on hanging sliders.

In life, like in baseball, sometimes the only thing to do is take the pitch because you can’t do anything useful with it.

Matthew M. Robare is a freelance journalist based in Boston who writes about urbanism and history. This article was supported by a grant from the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Does Small, Local Retail Matter?

Can communities support independent, local retailers while promoting economic development and downtown revitalization?

This was the key question at a panel on “Death by Chains?” in Providence, RI last week. The event was sponsored by the Congress for the New Urbanism New England Chapter, the R Street Institute, and The American Conservative.

One panelist suggested that ensuring a mix of businesses should take a backseat to general placemaking considerations. “My relationship to retail is secondary,” said Cliff Wood, the executive director of the Downtown Providence Parks Conservancy. “Now that we’re experiencing some success the chains are starting to knock on the door. Retail is in service to a larger mission.” According to its website, the DPPC promotes revitalizing downtown Providence with pedestrian-friendly public spaces.

Kip Bergstrom, who has held a variety of positions in economic development in Connecticut, said that the United States was overbuilt for retail, with roughly 10 times the square feet per person than in Europe. However, he said there is a mismatch, because much of the supply is in the form of suburban malls and shopping centers, but the demand is for more traditional venues.

“They’re looking for good urbanism,” Bergstrom said. “It’s not death by chain, it’s the death of the suburban shopping center.”

But retail is part of placemaking.

“Retail is the thing that makes a place interesting,” Bergstrom said. “Without retail you don’t have a place.”

He said that the big challenge in retail was affordability. Not only are there currently not enough good urban spaces, but if all the development suddenly switched to good urbanism, it would still be expensive to build initially. He suggested that new retail developments should use well-paying chain retail to keep rents low for independent, local retail.

Arts consultant Margaret Bodell said that local businesses can, in a way create their own demand.

“One of the things I see is that people want to be part of a community,” she said. “Supporting local businesses is what people want to do.”

Anne Haynes of MassDevelopment, an economic development agency, agreed with this idea. “Each store is a hub of community,” she said. “Most retail provides that.” Haynes works with Massachusetts’ “gateway cities,” places that were once fairly prosperous industrial hubs, but have experienced disinvestment and increases in poverty, unemployment, and crime.

Bodell’s community-building efforts focus on using the arts to enhance business districts with nice store fronts and pop-up stores. The biggest obstacle she faces, she said, is getting landlords to allow experimental approaches.

Jonathan Coppage of the R Street Institute said that Washington has created barriers to the good urbanism Bergstrom spoke about.

“There are significant obstacles for small developers trying to get off the ground because of the mixed-use nature,” he said. “When you have the organic mixture of uses—the federal government is not set up for that.”

Coppage said that there were no federal loans or loan guarantees for mixed-use urban buildings unless they were around six or more stories or the developer could get a customized loan from a local bank—which is not likely. He said that there needed to be more adaptive institutions.

Bergstrom said that R. John Anderson, an architect and urbanist who promotes small-scale, incremental development, had developed a template for a one-story retail building with two 900 square foot stores that’s designed to be affordable from the beginning.

“Why does small retail matter?” asked Coppage.

“I think that the most important thing about retail is the sense of creating your own destiny,” Haynes said. “When you see a chain store, you know that the decisions are not being made locally.”

Bergstrom said that he did a lot of traveling and observed that non-chain stores make neighborhoods more unique. “Upscale neighborhoods all look the same with the same high end chain stores,” he said. “It’s chic, but it’s generic chic.”

“People go to places when they want to be in those places,” said Wood. “There’s a ‘hereness’—people like where they are.”

But the problem is that as neighborhoods get more popular and local retailers are successful, the rents start going up until only the chains can afford them.

Bergstrom described the problem as one of creating control rods for the nuclear reaction of neighborhood space.

“Part of our agreements with cities to figure out how to be sustainable and support activity for the long term,” Haynes said. “It requires a person. We call it community engagement for economic development.”

One of the things the panelists agreed on was the importance of ownership. Bergstrom said that one of the important things about the retail building template was that it was designed to be rent-to-own.

Wood said that there was an artists’ squat in Providence called AS 220 that managed to gain control of their building through sweat equity.

“The clever thing they did was figure out how to be owners,” he said.

John DiGiovanni, a member of the Harvard Square Business Association in Cambridge, Mass., said he wasn’t concerned with chains at all.

“It’s all about place,” he said. “The successful spaces are about place and the businesses behind the door come and go.”

“If you can create you can participate in your community,” Bodell said.

Another issue mentioned was the problem of vacancies. In some cities, businesses will move around but keep an empty location leased. Bergstrom called that practice restraint of trade and said that Rhode Island had created a kind of land value tax to punish landlords who keep properties vacant.

Peter Friedrichs, director of the Central Falls, RI Office of Planning and Economic Development, said that it was called the non-utilization tax and was about three times the typical property tax.

“It’s an absolutely crucial tool,” he said.

“You can’t predict the market,” Haynes said. “The only thing you can depend on is a need for a diverse range of spaces.”

Matthew M. Robare is a freelance journalist based in Boston who writes about urbanism and history. This article was supported by a grant from the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Is Bad City Planning Making Us Lonely?

“Words on the Street” highlights the best writing on urbanism we’ve encountered this week. Post tips at @NewUrbs.

Loneliness, Urban Design, and Form-Based Codes | Steve Price, CNU Public Square

Humans are social, yet this primary fact of life is oddly absent as a core consideration in modern urban development regulations. To ignore the social needs of our species is to lose sight of one of the most positive drivers for shaping sustainable urban form. Providing for the satisfactions of community counters sprawl. Yet conventional land-use zoning disperses people and strips social life from the landscape. This is where form-based codes come in. They are the tool par excellence for guiding development in a socially sensitive way, configuring buildings and streets to enliven social life.

A remarkable and growing body of literature in contemporary social research is telling us that healthy, well functioning communities need face-to-face meeting, interaction, and communication among their members, something that electronic “social media” cannot replace. And it requires high quality physical space.

America’s Hunger for Luxury Housing May Finally Be Satiated | Jeff Spross, The Week

Around 5,100 new apartments will be listed for rent in San Francisco in 2016, which is the biggest annual number in 26 years; Manhattan will feature 5,675 new units. And 2017 will probably blow 2016 out of the water, with projections showing San Francisco gaining around 7,000 more units, and New York getting 14,000 new units. In fact, back in July, 2016 already looked set to meet or break apartment construction records in the major markets across the country. …

Much of this booming construction is in the super high-end market — it’s telling that the “low-end” market in Manhattan is considered to be all housing under $2 million. And it looks like the population that could afford to buy or rent those sorts of luxury units is dwindling: The number of highly paid tech jobs in San Francisco is down from a peak earlier this year, and it’s mid-pay jobs in hospitality and health care that are seeing the biggest gains in New York City.

Top-Down, Bottom-Up Urban Design | Elizabeth Greenspan, New Yorker

“[W]hat we need to do is think of the city as a more open system, which accumulates complexity, and in which those complexities have to be worked with, rather than simplified.” Take school buildings. In many cities, schools might be “built into factories, or into back rooms of housing settlements. And rather than see that there’s something wrong about that—this is what I mean about the break with the spirit of Corbusier—we should be working with making that kind of school better,” he said. [Richard] Sennett and his colleagues argue for city plans defined by flexibility, rather than by right and wrong answers.

An Uncredentialed Woman: The Unlikely Life of Jane Jacobs | Howard Husock, City Journal

Robert Kanigel’s Eyes on the Street is the first full-length biography of Jacobs, a woman without a college degree who became one of the most influential urban thinkers of the twentieth century. Kanigel deftly links Jacobs’s life experiences to the development of her original ideas. Born Jane Butzner in 1916 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Jacobs wrote for a living, and not always for glamorous New York publications. She began her journalism career as an intern at the Scranton Republican and then contributed to Iron Age, a trade publication at which she learned the nuts and bolts of the metals industry. She learned, for instance, that non-ferrous metals were vital to modern life and how the markets for them worked. She worked briefly as a financial writer for Hearst and wrote an extended feature about Manhattan’s fur district for Vogue and another for Harper’s Bazaar about the crabbing culture on Maryland’s Tangier Island. She was, in other words, soaking up the details of how business, culture, and the urban environment worked together when done right—the very combinations she’d go on to celebrate in her breakthrough masterpiece, 1961’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

New York, San Francisco, and the Real Rental Crisis | Jordan Fraade, Washington Post

Economists have traditionally defined “rent-burdened” households as those that pay more than 30 percent of their income in rent. The “severely rent-burdened” pay more than half. In all but two of the 11 largest metro areas in the United States, the share of low-income households that suffer from severe rent burden increased from 2006 to 2014, according to a March report by New York University’s Furman Center. Since 2008, rent burden has also become far more common among middle-class households, the combined result of stagnant incomes and declining rental vacancy. Pundits and demographers often hold up cities like Atlanta, Philadelphia and Chicago as reasonably priced alternatives to pricey coastal hubs. But these “second-tier” cities are hardly immune from their own affordability problems. By 2014, a majority of all renter households in eight of the 11 largest U.S. cities, including all three listed above, qualified as rent-burdened.

This post was supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

What the Rust Belt Can Learn from Rio

The hilariously mordant James Howard Kunstler once wrote a blog post about driving through northwest Indiana, noting the “ghostly remnants of factories” and neighborhoods “foreclosed and shuttered,” “places of such stunning, relentless dreariness that you felt depressed just imagining how depressed the remaining denizens of the endless blocks of run-down shoebox houses must feel…There was a Chernobyl-like grandeur to it, as of the longed-for end of something enormous that hadn’t worked out well.”

My own leafy town of Valparaiso is part of this region of over 700,000 that includes no major urban centers, only small cities and towns, none of them over 80,000. They include such locales as Gary, East Chicago, Hammond, Michigan City, La Porte, Crown Point, Portage and Chesterton. Thinking of the map of Lake Michigan, I sometimes describe our post-industrial landscape as “the bottom of the lake.”

Earlier this month, nearby this gritty spectacle at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Front Porch Republic held its annual meeting. (The name of the group sounds like a breakaway comic-opera kingdom, perhaps a cousin of Groucho Marx’s Fredonia. In fact, FPR is a collection of writers, academics and genial cranks who all emphasize the local over the remote.) In comments at Notre Dame, I wondered what exactly is supposed to be our collective fate here in “the region,” as locals like to call it. Is Creative Class guru Richard Florida correct that our lack of information-economy resources means we’re doomed to just fade away? Should we take Harvard economist Ed Glaeser’s advice and work to become more integrated into the neoliberal Chicago megaregion?

Perhaps what places like northern Indiana need is not innovation, but unnovation—to use a term coined by Boston-based journalist Ben Schreckinger. The idea is to resist the magical thinking that our little towns can ensure meteoric growth by trying to launch tech companies with virtually no resident tech talent. Forget Silicon Valley and Route 128 and the endless glorification of knowledge work (you might think of proto-Porcher Wendell Berry here): in the rustbelt, we need a return to economic roots. Schreckinger argues that non-urban Massachusetts—he might have said most of Indiana as well—should return to its traditional industries of farming and manufacturing, both of which have deep cultural roots (outside the big cities) as well as new technological tools.

Also worth considering is Catherine Tumber’s contrarian vision of the resilient post-industrial cities and towns of the future. She argues that pace the wiseguys like Florida or Glaeser, it is we rust-belters who are well-positioned for the future economy. That’s because our places will be “small, gritty and green” (from her book of the same name).

Here’s what she means. First, smaller cities and towns (under a half million in population) are built on a more sustainable scale and can often achieve consensus more easily. Second, their “grittiness” is their cultural memory of manufacturing and heavier industry, one example of which is Muncie, Indiana’s current national prominence in the wind energy sector, drawing on its history with corporations such as GM and Westinghouse. Finally, the greenness advantage derives from the way smaller cities and towns can benefit from and contribute to a clean energy economy based on land, manufacturing skills, waterways, and concentrated urban energy markets of their own.

Just for fun, I asked the audience at Notre Dame to guess the location of a real place which had the characteristics of low-rise, high density development; a pedestrian orientation; mixed use (homes above shops); organic architecture (evolves according to need); use of collective action; intricate solidarity networks; and vibrant cultural production. Sounds like Tolkien’s Shire, I know.

The place I had in mind, one I visited several years ago, was in fact the Rocinha favela in Rio de Janeiro. The economy of a Brazilian favela, in many instances, can be an example of a kind of anarchist, self-organizing system, still somewhat free from much governmental involvement—one among several ways in which it typically differs from, say, Chicago’s West Side. These are exuberant, street-lively places built with much more social than economic capital, leading to neighborhood sayings such as “there are no beggars in the favela.” Importantly, they have managed to develop and even prosper outside the usual financial and civic systems.

Given the presence of Rod Dreher at the conference, it was natural to ask: does the Benedict Option have an economic dimension? I suggested that it necessarily had one, citing the Economy of Communion network as a kind of model. The EoC was born within the Focolare organization—a Catholic “ecclesial movement” founded just after World War II—and now has some 700 member businesses worldwide. In its grounding in personalist Christian witness and Catholic social teachings, the group is no quaint collection of handicraft vendors but a sophisticated coalition of triple-bottom line companies. I think their vision offers an important way forward.

Elias Crim is a civic entrepreneur in Valparaiso, Indiana. He blogs at The Dorothy Option and Solidarity Hall.

This post was supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Will We Always Have Paris?

“Words on the Street” highlights the best writing on urbanism we’ve encountered this week. Post tips at @NewUrbs.

“We’ll Always Have Paris”? | Mary Campbell Gallagher, Architecture Here and There

When the masked thugs of ISIS swing their sledgehammers through Iraq’s museums and dynamite Palmyra, the world gasps and screams. But what if the vandal is a chic Parisian woman wearing high-heeled boots and talking like a visionary? What if her target is the world’s most beloved and most-visited city? Does the world gasp, or does it not even hear what she is saying? “We’ll always have Paris,” Rick tells Elsa in “Casablanca.” Yet now, Mayor Anne Hidalgo says she will “reinvent” Paris. Without putting it to a vote, she will replace the uniquely harmonious city we know with something “modern” and “contemporary.” She will pierce the low horizon with a dozen skyscrapers, replace classic stone facades with rivers of glass, and bury the famous zinc and slate rooftops under new construction. Mon Dieu! Doesn’t anyone get what Paris is doing to itself?

Why Cathedrals Are Soaring | Simon Jenkins, The Spectator

Something strange is happening in the long decline of Christian Britain. We know that church attendance has plummeted two thirds since the 1960s. Barely half of Britons call themselves Christian and only a tiny group of these go near a church. Just 1.4 per cent regularly worship as Anglicans, and many of those do so for a privileged place in a church school.

Yet one corner of the garden is blooming: the 42 cathedrals. At the end of the last century, cathedrals were faring no better than churches, with attendances falling sometimes by 5 per cent a year. With the new century, everything changed. Worship in almost all 42 Anglican cathedrals began to rise, and it is now up by a third in a decade. This was in addition to visits by tourists, who number more than eight million. There are more visits to cathedrals than to English Heritage properties.

Hartford’s Big Dig | Matthew Hennessey, City Journal

Every large city in Connecticut has at least one arterial highway slashing through its heart. Some have multiple elevated highways meeting in massive steel-and-concrete interchanges. The drive along I-95 from New York to Boston affords commanding views of Stamford, Bridgeport, and New Haven. Spend a little time on the surface streets of these cities, however, and the civic devastation wrought by their highways is hard to miss.

In Connecticut as in the rest of the country, massive interstate construction projects followed President Dwight Eisenhower’s signing of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. Cities like Hartford were then suffering massive traffic congestion problems, as rising postwar incomes spurred a boom in individual car ownership. In 1949, several major insurance companies asked the engineering firm Andrews and Clark to compile an “Arterial Plan for Hartford” under the direction of New Haven native Robert Moses. “Doctors, we are told, bury their mistakes, planners by the same token embalm theirs, and engineers inflict them on their children’s children,” wrote Moses in a cover letter. It was an oddly prophetic warning from a man blamed by many for ruining New York City with his car-dependent infrastructure projects.

The Disposable Post-War Suburb | Johnny Sanphillippo, Granola Shotgun

Back in the 1950’s Colerain Township was the recipient of a wave of respectable prosperous families who were crossing the municipal line out of Cincinnati. They drove through Mount Airy Forest and left behind high taxes, high crime, lower quality public services, old unfashionable buildings, and poor black people. If you couldn’t afford a brand new home and a car… you clearly didn’t belong.

The schools were new. The shopping centers and office parks were new. Tax revenue poured in. Police, teachers, and administrators were hired. Parks were created. Libraries opened. Life was very good.

Fast forward sixty five years. Everything that used to be shiny and new is now aging – not all of it well. There are now decades of accumulated salaries, pensions, and health care obligations for municipal workers, past and present. The roads, water pipes, lift stations, sewerage treatment plant, and public buildings are all in need of expensive maintenance. Tax revenue is in decline. This town like nearly every other town of its vintage is functionally insolvent.

Art Deco Los Angeles | John L. Dorman, New York Times

Several of them have been razed, and a few of the surviving ones are underused or vacant. Tourists gravitate toward the Bank Tower, which has an observation deck, or Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall. But before being literally overshadowed, these Art Deco treasures were once icons of downtown Los Angeles. And they still should be.

Most of the Art Deco buildings are smaller than the modern skyscrapers rising in the area, but they still soar. To explore them is to witness a grandeur that inspires you, unlike many skyscrapers, which merely surprise you. Because they arrived at a moment of economic expansion, they suggest the sense of endless possibility that permeated the city. I set off to get a glimpse of what those architectural dreamers were able to accomplish.

This post was supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Google Maps and What Makes a Neighborhood Interesting

Where are the most interesting streetscapes and popular destinations in your city? Even among your friends and colleagues, there might be some lively disagreement about that question. But recently, search giant Google weighed in on this question when it overhauled Google Maps this summer. Now it has a new feature, an creamsicle orange shading in certain city neighborhoods, that it calls “areas of interest.” But what makes a neighborhood interesting? And do Google’s new peachy orange blobs correspond to anyone’s idea of what constitutes interesting?

The addition was part of a graphic facelift for Google Maps, which was generally applauded in the design community. The new maps are a bit lighter, more prominently include neighborhood names, and highlight notable landmarks. Freeways and major arterials, parks, and the new peachy areas of interest are the outstanding features on these maps.

But not everyone was enamored of the new orange blotches. Writing at CityLab, Laura Bliss detected a bias. Could it be, she asked, that Google was only interested in areas with certain levels of income, ethnic compositions and levels of internet access? Examining data for selected neighborhoods in Washington, Los Angeles, and Boston, she argued that low income neighborhoods of color tended to be less likely to get Google’s peachy designation.

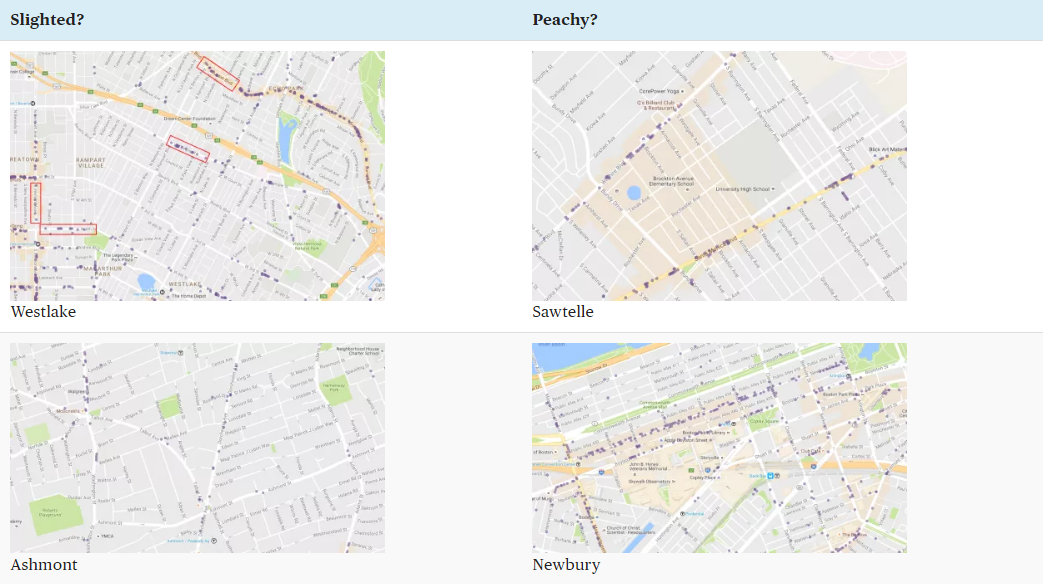

For example, while Westlake, a neighborhood towards the east side of Los Angeles is dense, relatively low-income, predominantly Latino area, with many restaurants, businesses, and schools only a few lots are highlighted in orange. In contrast, the mostly residential, mostly white neighborhood of Sawtelle, on the wealthier, west side of Los Angeles includes Wilshire and Santa Monica boulevards and a wide residential area, but the “nearly the entire area is shaded orange, for no clear reason.”

It’s a fair point to suggest that not everyone will find the same set of destinations “interesting,” and it’s likely given capitalism, demographics and math, that any algorithm-based means of identifying interesting areas will tend to select places that appeal to the masses, the mass market and the majority, and may leave out or fail to detect places that have appeal to subgroups of the population. And the fact that Google–while acknowledging that the presence of commercial activities influences its scoring– has been mostly vague about how it has identified areas of interest can add to the concern.

Earlier this year, at City Observatory, we set about tackling a similar question, using data on the location of customer-facing retail and service businesses to create a Storefront Index. Essentially, we used a business directory database to map the locations of millions of retail and service businesses, in the process identifying places that have strong clusters of these businesses that form the nuclei of walkable areas. The special sauce in the index is the use of a nearest neighbor algorithm that provides that we map a business only if it is within 100 meters of another storefront business.

Because our algorithm is transparent (you can see each dot on the map) and because we’ve made our methodology public (details here), we thought it would be interesting to compare the Storefront Index clusters with Google’s Areas of Interest. And in the process, perhaps we can marshal some evidence that will bear on Laura Bliss’s concern that there’s some latent bias hiding in the Google approach.

We’ve overlaid our storefront index map on Google Maps, so you can see how closely the two concepts align. We haven’t undertaken any kind of statistical analysis, but a casual visual inspection shows that most areas of interest do in fact have high concentrations of storefronts. Our City Observatory colleague, Dillon Mahmoudi has mapped storefronts in the 50 largest US metropolitan areas, and you can use this map to see how storefront clusters correspond to areas of interest. Here’s downtown Los Angeles. (Click on the image to visit City Observatory‘s interactive web page, with maps of other metropolitan areas).

Let’s take a closer look at a couple of the neighborhoods that Laura Bliss felt were slighted by Google Maps. The first row shows two neighborhoods in Los Angeles, the second row two neighborhoods in Boston. The neighborhoods on the left were ones with very few and small areas of interest according to Google (and perhaps under-appreciated, according to Bliss); the ones on the right have relatively large shaded areas of interest. The dots on each map correspond to our measure of storefronts–cluster of customer facing retail and service businesses. Both of the “slighted” neighborhoods do have some clusters of storefront businesses (though their numbers are smaller, and there concentrations less dense than in the corresponding “favored” neighborhoods in the right hand column. While we’ve come up well-short of reverse engineering Google’s algorithm, these data do suggest that storefronts are a key driver of areas of interest.

It’s a fair question to ask as to whose preferences are reflected in any description of an “area of interest.” Given the diversity of the population and the heterogeneity of tastes and interests, what will be interesting to some people will be banal or off-putting to others. Or maybe its a semantic problem: by describing some areas as “interesting,” it seems like Google may be implicitly characterizing other areas as “uninteresting.” Many of these concerns could be assuaged, we think, if Google chose to be a little more transparent about its basis for describing these areas, and if it called them by a different and more narrowly descriptive name, like “most searched” or “most popular.”

Ultimately, the solution to the problem Laura Bliss has identified may be democratization and competition. The more data (including everything geolocated on the web, including Google maps and listings, tweets, user reviews, and traffic data) are widely available to end users, and the more different people are crafting their own maps, the better we may be able to create images that reflect the diversity of interests of map users.

Joe Cortright is President and principal economist of Impresa, a consulting firm specializing in regional economic analysis, innovation and industry clusters. This post originally appeared at CityObservatory.org.

Words on the Street

“Words on the Street” highlights the best writing on urbanism we’ve encountered this week. Post tips at @NewUrbs.

One More Inglorious Pile on the Mall | Edward Rothstein, Wall Street Journal

The news that the Eisenhower family has dropped objections to a modified version of Frank Gehry’s vision for a $150 million proposed memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower on the Mall in Washington means that in a few years we will probably be subjected to something only marginally less kitschy and overblown than Mr. Gehry’s earlier vision: a four-acre extravaganza featuring three statues of Eisenhower—as Kansas farm boy, Supreme Allied Commander and president—with a 477-foot-wide woven-metal tapestry depicting Abilene, Kan., suspended from eight-story-tall limestone columns.

The architect will now alter the tapestry’s subject and may skim off some bloat, but enough of the original idea will surely remain to allow it to fit right in with the many other mediocre monuments that have been crowding the Mall and other public sites during the past 25 years.

Want Affordable Housing? Legalize Main Street | Jonathan Coppage, Washington Post

In a sign that market solutions for the United States’ growing housing affordability crisis are beginning to earn bipartisan support, the White House this week unveiled its “Housing Development Toolkit,” which encourages state and local policymakers to undertake a number of long-overdue reforms.

The tool kit draws on some of the best and most up-to-date research on housing affordability and cites such respected researchers as Harvard University economist Ed Glaeser. But for such reforms to benefit smaller and distressed communities, Washington needs to undo its own role in distorting the housing market. In short, the Federal Housing Administration has to relegalize Main Street.

Lean Streets, Small Blocks: the ‘Good Bones’ of Strong Communities | Robert Steuteville, Public Square

A body without good bones will fall apart. And as many of us have come to realize, streets are the bones of communities. A community that lacks good streets will suffer—in its economy, its social well-being, and its health.

When people who study cities and towns say that a place “has good bones,” they mean that it has a connected network of small blocks and “lean” (not overly wide) streets. The blocks probably hold at least a few fine old buildings, though some of them may have been neglected, since the last half of the 20th Century was often unkind to old places. Urban renewal and parking policies led to the loss of many buildings.

The urban fabric may be tattered. Traffic engineers may have widened the travel lanes, converted many streets to one-way, and cut down trees. Nonetheless, in good bones there is the potential for renaissance. The essential elements—lean streets and small blocks, a characteristic praised by Jane Jacobs—are resilient.

Is There Too Much Parking? | Nate Berg, The Guardian

“As parking regulations were put into zoning codes, most of the downtowns in many cities were just completely decimated,” says Michael Kodransky, global research manager for the Institute of Transportation and Development Policy. “What the cities got, in effect, was great parking. But nobody goes to a city because it has great parking.”

Increasingly, cities are rethinking this approach. As cities across the world begin to prioritise walkable urban development and the type of city living that does not require a car for every trip, city officials are beginning to move away from blanket policies of providing abundant parking. Many are adjusting zoning rules that require certain minimum amounts of parking for specific types of development. Others are tweaking prices to discourage driving as a default when other options are available. Some are even actively preventing new parking spaces from being built.

Urbanism, Texas-Style | Joel Kotkin et. al., City Journal

Of the cities I’ve called home, Austin has the most aspirational culture. People move to Washington, for example, to change the world, and often do so—for the worse. People come to Austin to build something new, earn their success, and have fun. Visit any one of the city’s coffeehouses, and new rounds of funding and pitches are in the air. Drive or bike anywhere on a weekend, and you’ll likely run into a festival that you had no idea was happening. Our zip code has more bars per capita than any other in the nation. Many are indoor-outdoor, which gives Austin a festive, public feel. Voices, music, and faces are all integral to the urban landscape here.

Out of Portland’s Shadow

It used to be easy to avoid the litany of error that inevitably followed “I’m from Vancouver, Washington,”—Canada? D.C.?—by offering the simpler, “I’m from Portland.” No confusion there, it’s true enough—and in its early seasons, the TV show Portlandia gave you something to talk about with strangers. But the changes of the last decade, and even the last few years, have made it harder to elide the state line between Washington and Oregon that is the Columbia River.

Both Portland and Vancouver have grown enormously, with the latter now boasting a population of 172,000—adding nearly 30,000 residents since 2000. One rejected annexation plan from 2006 would have added even more residents, surpassing Tacoma and Spokane to become Washington’s second largest city. Vancouver has also grown a personality beyond just the not-Portland sentiment expressed when “Keep Portland Weird” was answered with “Keep Vancouver Normal.”

My official hometown has been called Vantucky, The Couve—and the chip on Vancouver’s shoulder is perfectly understandable. It is, in fact, the first Vancouver, with the Canadian metropolis to the north only a very, very wealthy knockoff. Historic Fort Vancouver (a national park, actually) was the Pacific headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company until Americans scared the Brits north to Victoria, and it is the Pacific Northwest’s oldest permanent non-native settlement. What’s more, even before all that, Lewis and Clark gave it five stars on Yelp, or would have, calling it “the only desired situation for settlement west of the Rocky Mountains.”

I moved to the Midwest for college and now am attempting to live cheap as a young writer on the Eastern seaboard. But one early hop across the Columbia River was also a hop across state lines, and it’s left me confused about where I’m from ever since.

Before I was from Vancouver, I was born in Portland. My parents and mewling and squalling me shared a tiny apartment down the street from a Moroccan restaurant. Because they were house managers for a domestic violence shelter in the building, they didn’t pay rent, but today similar (though somewhat larger) one-bedroom pads go for $1,585. The apartment contracted when confronted with kid and crib, so in 1995 it was time to move across the river.

In the suburbs of Vancouver, which was then essentially a suburb of Portland—and remains treated as such by my father, who commutes to work in the larger city—my parents bought an 1800 square foot, three-bedroom ranch home on a quarter acre for $129,000. With providential timing, they sold in 2007 for $230,000, right before the market tanked. We had bought a new house, also on quarter acre, in 2004 for $329,000. My dad guesses it is probably worth $375,000 now, but prior to the Great Recession it likely went to $450,000, and receded below $300,000 at the nadir of the housing market.

But while I grew up attending school in church basements throughout Vancouver, and ostensibly lived there, for most of my life a few free hours has meant taking the 20 minute drive over the bridge to Portland. Downtown Vancouver had little to offer growing up, and the city was growing multipolar, its new developments and economic growth mainly happening in East Vancouver, away from the historic district. It was a 20 minute drive east to suburban sprawl—strip malls and McMansions—or the same time south to a real city with real neighborhoods.

The realness of Portland and her neighborhoods is a conversation for another day; it is admittedly the most gentrified city in the country. But that has produced delightful, walkable mixed-use hubs even beyond it’s exhaustively profiled Pearl district. Mississippi Ave., NE MLK, Hawthorne, NW 23rd—Portland is a city of streets that have their own identities even as they share in the oh-so-easily-satirized personality of the city. The culture orients around food, coffee, beer, weed, exercise, and the outdoors. We are happy Epicureans inclined to full-out hedonism.

But can I say “we” anymore? Vancouver isn’t just the weirdly distended, angsty suburb it used to be. The population has boomed and prices are rising on both sides of the river. If you had a baby now and could make the tiny one-bedroom apartment work, maybe you’d stick to that. With traffic as bad as it has become over the desperately-in-need-of-replacement I-5 bridge and Vancouver’s growth, buying your starter house up north and working in Portland isn’t the same calculation it was for my parents.

Meanwhile, Vancouver is finally building along its waterfront, while its downtown is growing and revitalizing. A new central library building’s opening in 2011 marks the turning point in my experience of the city, and I spent a lot of my last visit home on Main Street. (Shoutout to the Thirsty Sasquatch tap house giving Portland shops a real competitor.)

Sure, Portland has Powell’s City of Books, more than 100 breweries in its immediate environs, a seemingly limitless supply of new restaurants and food carts, and great neighborhoods. But it was almost called Boston. Vancouver is Vancouver, the first one. Fort Vancouver stands reconstructed with its wood palisade and towers, and the surrounding parkland, the neighboring airfield, and the barracks above are all roots for the city, a sustaining history. Even when we were completely overshadowed by the younger upstart on the Willamette next door, we could take pride in our past and place.

Micah Meadowcroft is an editorial assistant at The American Conservative.

This post was supported by a grant from the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Death By Chain?

New Urbanism has long been concerned with promoting vibrant Main Streets, corridors with local retail and small businesses that keep jobs and capital in their communities.

The American Conservative is partnering with the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) New England chapter and the R Street Institute to bring together leading voices on this issue. Join us in Providence, RI on October 20, from at 5:00 to 8:00pm at Aurora, 276 Westminster St., Providence, RI. More information is available here.

If you’re in New England and care about strong communities, you don’t want to miss this opportunity to meet:

- Cliff Wood, Executive Director of Downtown Providence Parks Commission

- Kip Bergstrom, former Deputy Commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development

- Margaret Bodell, a Connecticut-based art center consultant with experience repurposing storefronts

- Anne Haynes, Director of the Transformative Development program at MassDevelopment

- The discussion will be moderated by former TAC editor Jonathan Coppage, now visiting scholar at the R Street Institute.

General admission to the event is $20, but The American Conservative has a limited number of free tickets for our readers. If you wish to receive one, please RSVP with your full name and address to [email protected], with the subject line “New Urbs event.”