Donald Trump’s Triumph

The polls and pundits were wrong: Donald Trump not only outpaced expectations, all the way to the White House, but early exit polls suggest he did better with Hispanics and other minorities than Mitt Romney did. The Obama coalition did not turn out for Hillary Clinton. And the media was blindsided by the results because it had spent over a year portraying Trump as an unelectable extremist. The one-sidedness of the prestige media—which featured as conservative and Republican voices on its op-ed pages and TV programs only anti-Trump figures such as Michael Gerson, David Brooks, Bill Kristol, and Stuart Stevens—deluded the elites themselves about the mood of the country.

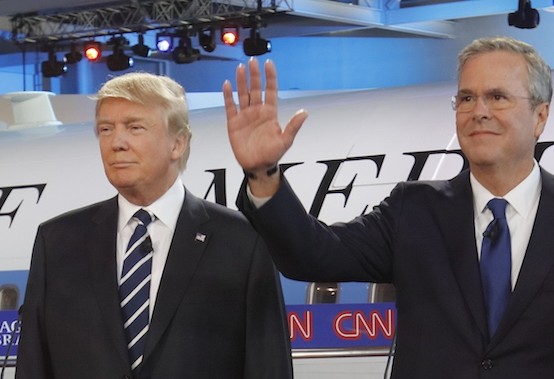

The prospect of a Clinton-Bush race 18 months ago was revolting to the American public, so much so that Republicans humiliated Jeb Bush in the primaries and awarded their nomination instead to the most anti-establishment candidate, Donald Trump. The Democrats, with some skulduggery, gave their nomination to Hillary Clinton, a figure who embodied the political establishment of the last 25-odd years. She had voted for Republican wars as well as ginning up intervention in the Libyan conflict. She was as close to the big banks as any politician in America. And she was not only the inevitable nominee of the Democratic Party, she seemed inevitably to be the next president. But the American people disagreed, and so did Donald Trump.

Trump won on themes of overhauling our foreign policy—America doesn’t win any more, he rightly observed—and renegotiating trade deals that have failed to serve the American workforce. He wants to secure the border and ensure that immigration is lawful and limited. Trump’s words have sometimes been blunt, and his policy proposals have often been eclectic—that’s to be expected; he’s a businessman, not a professional politician or wonk. (That’s exactly what the public was not voting for.) But his broad themes have been themes that readers of The American Conservative have understood as central to the task of preserving our country and upholding the principles of a republic, not a world empire.

The hard work begins once President Trump is sworn in, of course. He’ll have to build a cabinet of other leaders with Trump-like qualities, and complementary traits, assembling a team of advisors and policy-makers who will faithfully implement his vision. Trump faces a challenge similar to the one Ronald Reagan confronted and had only partial success in overcoming: namely, that of finding enough good people to take the reins of government. Without the president discovering better new talent, the usual suspect will quickly return: the ones who gave us the Iraq War and whose economics led to the Great Recession.

As difficult as this task may be, the first step, ridding America of the political dynasties that have ruled it for the better part of two decades, has been accomplished, and now the next battles can be fought—and, if Trump sticks to the themes that got him elected, won. This is an historic hour, and America has possibilities anew—possibilities that would have been forever precluded by an endless succession of Bushes and Clintons.

Daniel McCarthy is the editor of The American Conservative.

After Trump vs. Clinton

The 2016 election presents the starkest choice American voters have faced in at least 40 years. On one side is a nominee unlike any the country has seen before: a billionaire businessman and celebrity without a day’s experience in political office. On the other side is the first woman ever to be a major-party’s nominee: a woman with experience as a U.S. senator and secretary of state and who has already lived in the White House as first lady.

Hillary Clinton represents everything the country’s political elite believes in: the perpetuation and exercise of U.S. global power; trade deals and immigration for the sake of the economy; a privileged position for the big banks; and a culture of steady liberal progress that transcends the limits of the nation state and the historic West.

Donald Trump, on the other hand, is satan: an old, rich, white man of “isolationist” and nationalistic tendencies who transgresses against every stricture of political correctness (and a good many precepts of common decency). For at least the last 24 years, every election has pitted a Republican globalist against Democratic one, both candidates unblinking in their support for NATO and NAFTA: Bush (I), Clinton (I), Dole, Gore, Bush (II), Kerry, McCain, Obama, Romney. And now Clinton (II). But Trump breaks the mold.

So what—he’ll lose, won’t he? Yes, probably. But if he does, he’ll lose like Barry Goldwater or George McGovern: that is, not in a landslide, but in a way that redefines politics even in defeat. And unless a technologically driven economic miracle similar to the one that took place under Clinton (I) happens under Clinton (II), the public’s appetite for anti-globalist politics will only grow. Pat Buchanan raised the issues of war, trade, and immigration 20 years ago, but they lost salience amid the prosperity of the 1990s. By 2000 even right-wing voters were contented enough to settle for another Bush—especially against the then explicitly progressive John McCain—rather than take a risk on Buchanan. But after the Iraq War and the Great Recession, after killing bin Laden and Gaddafi only led to new waves of terror, voters on the right have proved more willing than ever to reject the post-Cold War consensus. Voters on the left, especially millennials, have begun to do so as well, as Bernie Sanders’s campaign illustrated. The consensus is under siege from the nationalist right and the democratic-socialist left alike—and that’s something Hillary Clinton, the personification of the consensus, is unlikely to know how to fix.

If Trump wins, he will be the most transformative president for his own party since Bill Clinton. Pro-life Democrats, welfarist Democrats, and Southern Democrats were all swept away or willingly left the party during the Clinton years. Would President Trump similarly cause an exodus of Republicans—or would he prove to be the anti-Clinton in more ways than one, bringing new elements into the party and broadening its ideological compass, just as he would seek to reverse Clinton’s trade, immigration, and foreign policies? Could a nationalist politics also be pragmatic and accommodating—and where would this leave conservatives?

All of this is only grist for speculation, but some things can be said with certainty, especially in foreign policy. First, the rise of a nationalist right with Trump and the parallel—but occasionally intersecting—rise of libertarian foreign-policy perspectives with the efforts of Ron and Rand Paul and the tug of non-interventionism even on Gary Johnson (a man who seems to know little and care less about world affairs) poses a standing challenge to primacist internationalism of what can fairly be called the Clinton-Bush consensus. Whether Trump or Clinton is the next president, there will be a struggle over the basic direction of U.S. foreign policy, a struggle pitting primacists on left and right alike against thinkers who prioritize the nation state and the national interest.

Second, Russia will be a flashpoint of strategic contention in the next administration, whether that means President Trump seeking a new relationship with Moscow or President Clinton setting out to confront and chastise Putin for involvement in Ukraine, Syria, and elsewhere. The military risks—up to and including the ultimate risk of nuclear war—are grave. Yet also deserving of serious consideration is a cultural question: what is Russia’s relationship to Western civilization, particularly to its Christian roots, in an age of jihadism, mass migration, and European secularization? The civilizational and the strategic questions are, of course, related—in complex ways that are apt not to be appreciated by the reductionist thinkers of the liberal consensus. (If anything cannot be described in terms of human rights or GDP, liberals don’t believe it exists or can matter—except perhaps as a pathology.)

Third, President Trump or President Clinton will be faced equally with the strict limits of American military power in terms of personnel, materiel, money, and morale. The costs of veterans’ care and new military hardware will only rise, while the “sequester” that has controlled defense spending since 2013 will remain a target for hawks and pork-lovers in both parties. The American people, meanwhile, are alarmed by ISIS and the prospect of Islamist terror yet weary of sending their children to fight and die in foreign lands. Whether President Trump wants to fight ISIS and “take their oil” or President Clinton hopes to engineer regime change in Syria without “boots on the ground” (except for special forces and “advisors,” of course), the American public’s skepticism of further Mideast misadventures may give Congress an opportunity to reassert its constitutional role in war and foreign policy. But does Congress have the guts to live up to its duty?

Fourth, and relatedly, there is the unavoidable fact that American policy in the Middle East and the wider Islamic world—what Andrew Bacevich calls America’s War for the Greater Middle East—has failed. Neither George W. Bush nor Barack Obama was able to wrap-up the Afghan War, now by far America’s longest-lasting conflict, one that has no clear end or goal in sight. Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Yemen bleed, as do the civilian casualties—mere “collateral damage”—of drone strikes throughout the region. Obama has already discovered that simply continuing the policies established by George W. Bush provides no answers, and no matter how much continuity Clinton may wish to see between her administration and Obama’s (assuming she wishes to see any), a new approach to the Middle East and Islamic world appears imperative. And will be all the more so if Trump becomes president. Should America be militarily involved in the region at all?

The struggle to answer these questions and address these challenges will begin the minute the results of the vote on November 8 are known: globalists and interventionists in both parties have their programs ready to go and their personnel ready to fill the ranks of the next administration, no matter who wins. The other side—the coalition of peace, restraint, and realism—is still new and largely ad hoc. But it must be ready, too, and The American Conservative will do its part to make it so. The conference we have been advertising for a few weeks now—set for November 15, one week after the election—will be a first salvo in the war of ideas over the next administration’s foreign policy. We have conservatives and libertarians, current and former office-holders—including James Webb, former senator and former secretary of the Navy—and leading scholars and journalists (such as Andrew Bacevich and James Pinkerton) lined up to discuss these issues (and more).

I hope you can join us for “Foreign Policy in America’s Interest: Realism, Nationalism, and the National Interest.” The event is free, and it takes places at George Washington University’s Jack Morton auditorium from 8 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. on November 15. You can register here. And you can help us make this event a success—and keep The American Conservative going strong—by making a secure electronic donation here.

A new era is beginning in American politics, not only one that will see nationalism and globalism contend for the soul of the next administration but one that will give rise to new permutations of conservatism, realism, and libertarian foreign-policy thought. Whether we are to have a world of sovereign nation-states or one in which a single imperial superpower contends with increasingly fragmentary post-national and sub-national threats around the globe will depend on the decisions that are made in the near future: in the next few years. There is peril in either direction, but self-government still depends on the nation-state. TAC has been laying the groundwork for a return to the national interest and America’s republican tradition in foreign policy since its first issue in 2002. And in the next administration, amid the battle to redefine conservatism, TAC aims to make a decisive difference.

Daniel McCarthy is the editor of The American Conservative.

Follow @ToryAnarchist

Trump Beats Clinton the Way He Beat Bush

The end of May has brought terrible news for Donald Trump, as conventional wisdom would have it. Over Memorial Day weekend, the Libertarian Party nominated two Republican ex-governors, Gary Johnson and William Weld, as its ticket for November, while Bill Kristol assured Twitter that there would be neoconservative-friendly “independent” on the ballot as well. Hillary Clinton led Trump by just 1 point in the RealClearPolitics aggregate of national polling, but as polls catch up to these events, Trump is sunk. Isn’t he?

Not so fast. First, take a look at the electoral map Trump inherits from Mitt Romney. The 2012 Republican nominee did not, of course, win enough states to become president, but where he did win, he won by comfortable margins: those are Trump’s margins now. Of the states Romney won, there were only two that he took by less than 10 percent: North Carolina and Georgia. Trump seems like at least as good a cultural fit for the Republican elements in those states as Romney was. And the states Romney won by “only” ten points—the next closest GOP margins—were Missouri and Indiana, which seem apt to be all the more enthusiastic about this year’s nominee.

Indiana and Missouri were two of the best states for Gary Johnson as the Libertarian nominee in 2012; they respectively gave him 1.91 percent and 1.57 percent of their votes. If Johnson/Weld does fully twice as well in 2016—which, for reasons to be mentioned shortly, is improbable—a 4 percent and 3.1 Libertarian vote in those states would still not stop Trump from winning them. Even a doubling of the Libertarian vote in Georgia, another place where Johnson ran ahead of his national percentage in 2012, would not tip the scales: the Libertarian Party vote would go from less than 1.2 percent of the vote to about 2.4 percent, in a state that Romney won in 2012 by nearly 8 points.

But couldn’t Johnson do much more than 100 percent better in 2016? After all, Trump and Clinton have the highest negative ratings of any major-party nominees since CBS began polling on the question in 1984. This creates an opening, if ever there was one, for another option—if not a Libertarian, perhaps a candidate with Bill Kristol’s “Renegade Party.”

Unfortunately for Kristol and Johnson, that’s not how politics works in 21st-century America: the sky-high negatives for both nominees mean there is in fact less space than usual for a third-party (or fourth-party) challenger, for the simple reason that voting against someone they hate is more important to more voters than voting for someone they like. The most important numbers for Trump aren’t ones that might attest to his popularity but those that demonstrate disapproval of Hillary Clinton. Votes against Clinton, in the abstract, could be votes for Johnson or the Kristol candidate, but in practice voters who are serious about stopping Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party will all but inevitably vote for the major-party alternative: Trump and the GOP.

Look again at the list of states where Gary Johnson performed best in 2012: voters in places like Alaska and Wyoming had the luxury of casting their ballots for an exotic species of Republican, called a “Libertarian,” because a Republican was sure to win the state anyway. Johnson’s 2012 ticket underperformed its national average in states like Ohio, Florida, and Virginia. No battleground state appears in the ranking of places where the Libertarians did best. (A few Democratic states, where again the outcome was predetermined and Republicans might as well vote for a Republican subspecies, do make the list: this explains why Illinois is more Libertarian than Virginia.)

My small-l libertarian friends bristle at being labeled “conservatives” or “Republicans,” but at the ballot box a difference is hard to discern: the Libertarian Party has never nominated a well-known ex-Democrat to its ticket but has frequently nominated Republicans such as Ron Paul, Bob Barr, Gary Johnson, and William Weld. Wayne Allyn Root, the LP’s 2008 vice presidential nominee, is an eager Trump supporter today. And not only the nominees but also the Libertarian Party’s voters, to judge by the numbers, seem mostly to be “alternative Republicans.”

What might seem like a greater threat to Trump is a Kristol candidate targeted specifically at Virginia, whose D.C. suburbs are perhaps the only place in the country where NeverTrump Republicans could make a critical difference in November. (Other states have plenty of anti-Trump Republicans, but those states are so Republican anyway that the defections don’t matter, just as defections to the Libertarian Party don’t.) Yet it’s not clear that there is a Virginia-marketable neoconservative Republican who wouldn’t risk taking as many votes from neoconservative-friendly Clinton as from Trump. In Virginia, splitting the vote for war, NAFTA, and more immigration between Clinton and a Kristol candidate might work to Trump’s advantage, in much the same way that the divided field in the Republican primaries did.

All this only means that Trump should do as well as Romney did in the electoral college; the alt Republicans and #NeverTrump effort have little chance of costing Trump anti-Clinton votes, which is what most Republican votes are. (One of the flaws in my analysis of the Trump phenomenon early on was that I continued to believe most Republican voters were attached to their party and wanted to nominate someone “electable”; in fact, a plurality of Republican voters hates the establishment in both parties and wants to take a stand against it, even if that means nominating seemingly “unelectable” candidates like Trump or many a Tea Partier.)

Romney fell far short of beating Obama, of course, and since 2012 the country’s demographics have only moved further in a Democratic direction, as more millennials come of voting age and the white proportion of the electorate declines. Surely this dooms Trump, even if Republican divisions do not.

Except it doesn’t, not by itself. Jamelle Bouie suggests that “If Trump could reverse the yearslong decline and bring white turnout back to its 2008 levels—74 percent—then he could win with another couple percentage points among whites [more than what McCain received] … This would give him teetering Democratic states such as New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, as well as the three largest swing states: Florida, Ohio, and Virginia.”

(Higher white turnout in 2016 compared to 2012 strikes Bouie as a more plausible winning scenario for Trump than one in which Trump gets a much higher proportion of a 2012-sized white vote: for the latter to work, he would need “an increase of nearly six points over the [GOP’s] white share in 2012, matching Ronald Reagan’s performance in 1984.”)

Even where 21st-century demographics are concerned, Trump may have more of a shot than his dismal polling among young people and racial minorities suggests. Clinton is weak with young voters as well, and the tensions between Clinton’s establishment liberal supporters and the young left have already led to severed alliances and think-tank purges. Trump has an opening—if not to add young voters to his older and whiter base then nevertheless to deprive Clinton of their votes by hammering home her failures. And if Trump could win even in the Republican primaries with forceful opposition to the Iraq War and secretive trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)—causes that resonate with Sanders-leaning young voters—he stands to do better still with those positions in the general election. Clinton personifies the old consensus that Obama’s millennial vote was trying to get rid of when it embraced “Hope and Change.”

Trump has shown he’s prepared to campaign much more aggressively on foreign policy than Bernie Sanders has ever dared. And for a preview of how Trump will perform against Clinton in a debate, just recall how he performed against the GOP’s closest counterpart to Clinton: Jeb Bush. Trump will press her hard on Iraq, much harder than Sanders has done. He’ll hit her on Libya, too. Trump also won’t be any kinder than Sanders has been about Clinton’s coziness with the big banks. The young left may be in for a surprise—one that’s unlikely to lead many to vote for Trump but that may drive deeper the generational wedge between them and Clinton.

The 2016 race pits a decades-old center-left establishment against a newly invigorated populist right. That populist right has already defeated the decades-old center-right establishment of the GOP. It has a fighting chance against Clinton, if Trump sticks to his issues and doesn’t attempt to become a more generic, Romney-like Republican on questions of war and industrial policy.

As for immigration and ethno-racial politics, there could be some surprises here, too. Trump’s critics in the media identify him with the racist and anti-Semitic trolls who support him on Twitter; but millions more Americans identify the Democratic Party with the Social Justice Warriors and other activists whose antics and occasionally violent acts have been widely broadcast on national television over the past two years. If Clinton repudiates this Social Justice left, she risks further alienating her young left base; if she fails to repudiate them, she stands to alienate more of Middle America.

Hillary Clinton represents everything that Trump voters, Republicans, Sanders voters, and Middle America have come to hate: the Iraq War, secretive trade deals and job losses, suffocating political correctness, and the risk of “unrest.” The liberal establishment in both parties—free-market liberal in the GOP’s case, left-liberal in the Democrats’—has known all along how much suffering and resentment its policies have generated. But party elites imagined that none of it mattered: what could voters do, pull the lever for Bush instead of Clinton? Clinton instead of Bush? The fix was in, and had been since the first George Bush took office.

Only now, to the insiders’ dismay, voters have an establishment and an anti-establishment choice. In 2008 they selected the relatively less establishment figure, Barack Obama, in the Democratic primaries and general election alike. In 2016, voters are asked to cast their ballots for the Democrat who didn’t represent hope or change eight years ago. Is Clinton any fresher today?

Trump won’t lose any of Romney’s states. Can Clinton really hold all of Obama’s? Probably not: Ohio still has some white working-class Democrats, and Trump’s prospects of winning them seem a lot better than Mitt Romney’s ever were. Trump surprised everyone with his successes in Pennsylvania’s GOP primary; if he can do five points better than Romney in the general election there, the results will be catastrophic for Clinton. Florida remains as much of a battleground as ever: there’s no indication that any trouble with Latino voters will cost him the Sunshine State. This election is as finely balanced and close as 2012 was, and that brings it down to a referendum on the status quo of the last 20 years: should the era of Bush and Clinton continue, or is it time for something new—even if what’s new is named Donald Trump?

Daniel McCarthy is the editor of The American Conservative. Follow @ToryAnarchist//

I Was Wrong About Trump

Last July I wrote that Donald Trump was merely a “blip,” a novelty candidate who couldn’t do much better than 17 percent in the polls. He would swiftly go the way of Herman Cain.

In August, I still didn’t believe the Trump hype. The 2016 race, I predicted, would see an early surge for a religious right candidate, followed by the inevitable nomination of the establishment favorite, probably Jeb Bush. After the Iowa caucuses, I was sure my scenario was playing out, only with Rubio in place Bush.

I was as wrong about Trump’s popularity as it’s possible to get. But I got a few things right, and it’s worth accounting for how I could miss the big story while getting much of the background right.

The simplest answer, if an incomplete one, is that Trump filled exactly the space I expected to be taken by the establishment’s candidate. The race has indeed come down to the front-runner and the candidate with the most appeal to the religious right (Cruz). Only the front-runner isn’t the establishment’s man, it’s Trump.

One mistake I made at the outset, in my July story, was to discount the value of Trump’s celebrity and command of the media relative to Jeb Bush’s super PAC millions. Earned media beat paid media hands down. But something more fundamental accounts for Trump’s success and Bush’s failure, a change in the Republican electorate that I willfully overlooked.

Evidence of that change was plain for all to see: Republican voters who once had seemingly prioritized electability were now prioritizing outsiderdom. The Tea Party had illustrated this as far back as 2010. In Delaware, a state not known as a hotbed of right-wing activity, Republican voters that year sacrificed a chance to win a U.S. Senate seat with the moderate Rep. Mike Castle and instead nominated a right-leaning minor media figure who had never held elective office: Christine O’Donnell. She was only the most telling of several weak outsider candidates the Tea Party propelled to victory in Republican contests and then defeat in November, that year and in subsequent cycles. The Tea Party did, of course, also notch up several victories with outsider candidates: with Rand Paul and Mike Lee in 2010, for example, and with Ted Cruz in 2012. All of these Tea Party Republicans, winners and losers, beat establishment shoo-ins. Republican voters seemed less concerned about winning or losing than about nominating someone who would take on the GOP’s insiders as well as the Democrats.

But those were mostly midterm elections, at any rate congressional or state elections, and surely the presidential nomination was another matter entirely. Grassroots activists might swing the outcome of an off-year primary or a state convention, but presidential primaries brought out your unexcitable, pragmatic, bread-and-butter Republicans, the ones who had nominated Ford in ’76, Dole in ’96, and who did, in fact, nominate Mitt Romney in 2012.

The party seemed to follow a pattern from 1968 onwards of always nominating the most familiar name, usually the previous cycle’s runner-up: Nixon, Ford, Reagan, Bush I, Dole, Bush II, McCain, and Romney. And the only nominees since World War II who weren’t favored by the party’s elite, Goldwater in 1964 and Reagan in 1980, were only partial exceptions to the GOP’s establishmentarian bent. Goldwater had paid his dues as head of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, and the conditions of the 1964 election made that year’s nomination a rather dubious prize for whoever might win it. Reagan, meanwhile, had been governor of California and only won the nomination in 1980 after having been rebuffed in 1976 and 1968.

Romney’s cruise to the nomination in 2012 fit exactly the model I expected—the one I went badly wrong with by applying to the 2016 race. I should have paid closer attention to something that had surprised me in 2012, something that in retrospect was an obvious harbinger of Trump: Newt Gingrich’s victory in that year’s South Carolina primary. That was significant because South Carolina, despite its reputation for being a right-wing state, had in fact been an establishment bulwark in past cycles. To be sure, John McCain, whose insurgent candidacy in 2000 was styled as more reformist and progressive than George W. Bush’s, was opposed by right-leaning Republican voters as well as establishmentarian ones in that year’s South Carolina contest. But South Carolina had also blocked Pat Buchanan in 1996, and for all the vaunted strength of the religious right in the Palmetto State, Christian conservatives like Mike Huckabee always lost South Carolina, even when they won Iowa.

Gingrich’s victory, however, showed that by 2012, South Carolina voters were not interested in robotically voting for the most supposedly electable candidate—the establishment’s pick and the last cycle’s runner-up. And if I’d really paid attention, I would have noticed that whoever the voters supporting Gingrich were, they were not the kind of religious right voters whose behavior elsewhere–in Iowa, for example—might be predictable. South Carolina in 2012 previewed a 2016 cycle in which neither electability nor ideological purity would be voters’ top priority. (Gingrich is viewed by many progressives as the living embodiment of conservatism, but on the right Gingrich has long been seen as a wildly heterodox figure. Gingrich is fervently but informally backing Trump this year.)

If Gingrich was a surprise in South Carolina four years ago, bigger surprises over the last two years should have been as much of a wake-up call as I, or anyone else, needed. In 2014, Republican primary voters in Virginia toppled the House majority leader, Rep. Eric Cantor, and nominated a right-leaning economics professor with no political experience in his place. Cantor, along with Reps. Kevin McCarthy and Paul Ryan, was touted by insider Republicans and the conservative establishment in DC as a “Young Gun”—the future of the Republican Party. But actual Republican voters opted for an alternate future. And last year, the rising tide of insurgency in the GOP took down an even bigger gun—if not a young one—the House speaker himself, John Boehner. After Boehner’s resignation, Paul Ryan picked up the gavel with some reluctance. Many mainstream journalists and establishment conservatives in the media have suggested that Ryan could be the GOP’s nominee this summer in a contested convention. I suspect Ryan can read the writing on the wall better than that: his fate will be the same as his predecessor’s and the same as his fellow young gun’s if he gets on the wrong side of the outsider wave.

Cantor’s fall and Boehner’s resignation showed that the establishment, whose fearsome power I overestimated in my predictions about Bush and Rubio, had already been crippled before Trump arrived on the scene. The Tea Party had shown, too, that from Delaware to Utah to Kentucky to Texas, Republican voters were as hostile toward their party’s establishment as they were toward Democrats. Maybe more so, in the case of places where hopeless candidates like O’Donnell were nominated, giving establishment Republicans a black eye but guaranteeing the Democrats a Senate seat. The Trump phenomenon expresses much the same priority among Republican voters: better to lose with Trump, a plurality of Republicans are saying, than win with Bush or Rubio. (And a fortiori, better to win or lose with Trump than lose with Bush or Rubio.)

My theory from August that the runner-up in this year’s contest would be the religious right’s champion has been half-correct. Cruz is indeed the second-place candidate in terms of votes and delegates, and Cruz has been winning those voters who are most religious—though Trump has proved to have plenty of pull with evangelicals himself. But in August I highlighted the differences between the religious right and other conservative voters. Cruz, by contrast, has become the candidate of movement conservatives, the religious right, and, however reluctantly, the Republican establishment itself, yet all of that is still not enough to beat Trump. I had thought that the split between the religious right and Goldwater-Reagan conservatives explained their failure to beat the establishment in years past. But even together with the establishment, they can’t overcome the outsider insurgency and the Donald.

But that leads me to reaffirm my analysis from July, when I got Trump and Bush so spectacularly wrong. Because what I did get right I was even more right about than I knew. Namely:

none of the factions—the libertarians, the religious right, the Tea Party—have much life in them. After all the sound and fury of the Obama years, no quarter of the right has generated ideas or leaders that compellingly appeal even to other Republicans, let alone to anyone outside the party. … The various factions’ policies aren’t generating any excitement, which leaves room for an outsize, outrageous personality, in this case Trump, to grab attention.

Trump succeeds because of more than outsize personality, of course. He attracts some support from everyone who thinks that Conservatism, Inc. and the GOP establishment are self-serving frauds—everyone who feels betrayed by the party and its ideological publicists. Working-class whites know that the Republican Party isn’t their party. Christian conservatives who in the past have supported Mike Huckabee and Ben Carson also know that the GOP won’t deliver for them. Moderates have been steadily alienated from the GOP by movement conservatives, yet hard-right immigration opponents feel marginalized by the party as well. Paleoconservatives and antiwar conservatives have been excommunicated on more than one occasion by the same establishment that’s now losing control to Trump. They can only applaud what Trump’s doing, even if Trump himself is no Pat Buchanan or Ron Paul.

Conservative Republicans™ somehow maneuvered themselves into a position of being too hardline for moderates and non-ideologues, but not hardline or ideological enough for the right. Trump, on the other hand, appeals both to the hard right and to voters whose economic interests would, in decades past, have classed them as moderates of the center-left—lunch-pail voters.

What’s even more remarkable is that movement conservatives, who have been given plenty of warning, ever since 2006, that their formula is exhausted, keep doing the same thing over and over again: they’ll dodge right, in a way that right-wingers find unsatisfactory but that moderates find appalling; then they’ll weave back to the center, in a way that doesn’t fool centrists and only angers the right. Immigration—which was another of George W. Bush’s stumbling blocks, lest we forget—has been the issue that symbolized movement-conservative Republicanism’s futility most poignantly. It’s not even clear that most GOP voters agree with Trump’s rhetorical hard-line on immigration—they just like it better than the two-faced talk of the average Republican politician.

Trump has a plethora of weaknesses, as general election polls amply demonstrate. But just look what he’s up against within the Republican Party: that’s why he’s winning. I should have recognized that last summer, but I thought voters would never break their habit of preferring “electable” candidates. It turns out that voters have much more capacity to learn and adapt—even if only by trial and error—than Republican elites do.

What Cruz vs. Trump Means

Donald Trump will go to the Republican convention in Cleveland with more delegates than anyone else. But it’s still possible he won’t have an outright majority. The mechanics of a contested convention have been covered at length in TAC and elsewhere. But what about the politics—who actually emerges as the Republican nominee?

The simplest answer is Ted Cruz. He’ll have the second largest number of delegates, as well as the symbolically important second largest number of popular votes. Although his Senate colleagues dislike and have been slow to endorse him, he has in fact assembled a broad coalition of support on the right, from former Jeb Bush advisors to the Senate’s most policy-minded conservative, Mike Lee. Cruz is the obvious pole around which to consolidate anti-Trump forces.

A two-man contest between Trump and Cruz is clarifying for movement conservatism. Cruz is what movement conservatism consciously created—somewhat to its own regret. The Texas senator checks every ideological box for the movement, from cutting government to talking tough in foreign policy to opposing abortion and same-sex marriage. Cruz wants to restrict immigration, but he’s more favorable toward free trade than Trump is. That’s roughly where the center of gravity for movement conservatism lies as well. The trouble is that Cruz has used these issues to advance himself in a way that has embarrassed his fellow movement conservatives. Instead of being kept in line by his adherence to movement orthodoxy, he has exploited his mastery of that orthodoxy to make himself a star.

Trump, on the other hand, is what movement conservatism has unconsciously created—a populist, economically nationalist backlash against a movement whose priorities are chiefly those of wealthy and upper-middle-class whites. This is even true where social issues are concerned: the poorest white Americans may not be supporters of same-sex marriage or abortion rights, but when given the choice they prioritize other issues more fundamentally connected to their lives. In this, lower-class whites are similar to black and Hispanic Americans, who remain firmly part of the Democratic coalition—despite much talk from movement conservatives about black and Hispanic qualms over abortion and homosexuality—because economics and group status are the things that matter most.

The practical, short-term question for Republicans choosing between Trump and Cruz is not so much whether either of them can beat Hillary Clinton—that may ultimately depend on her legal troubles—as it is which of them will do the least damage to down-ticket Republicans. U.S. Senators Mark Kirk (Ill.), Kelly Ayotte (N.H.), Pat Toomey (Penn.), and Rob Portman (Ohio) are all vulnerable, as is the Senate seat being vacated in Florida by Marco Rubio. Cruz is less toxic for the party overall—he may be widely disliked by his colleagues, but as controversial as he is, he’s nowhere near as controversial as Trump. Yet one might wonder whether Cruz is really the stronger top of the ticket for struggling Republicans in some of these battleground states, where Trump’s working-class demographic could be critical.

In any event, the long-term, existential question may supersede short-term calculations. This is the question of exactly whose party the GOP is supposed to be and how it can again win elections at every level. The lower-class whites who respond most favorably to Trump have been an indispensable but subordinate element in the Republican coalition for decades. Trump has revealed just how sharply at odds this group’s attitudes are with those of the GOP elite. And looking at the policies that the most elite Republicans support—policies identified with Marco Rubio, for example—it’s obvious that they are intended to build a new base for the party while the white working class is consigned to gradual decline. Trump voters’ jobs are being eliminated by technology and trade deals, while the voters themselves are to be replaced by a larger Republican share of the Hispanic vote.

Ted Cruz, despite his Canadian-Cuban background, hardly seems like the leader to usher the Republican Party toward a multicultural future. But if Cruz is only a halting step forward, in the eyes of the most enlightened Republicans, Trump would be a great leap backward. The Republican elite might have preferred Rubio, or anyone else but Trump, over Cruz. Yet it’s hard to see any other choice emerging at the convention. The notion that Cruz or Trump delegates—who together will make up the overwhelmingly majority—would switch to Kasich seems farfetched. A failed candidate from earlier in the presidential contest, say Scott Walker or Rick Perry, might be more plausible, but not by much. Again, why would Cruz people defect?

Leading Republicans who haven’t been candidates this cycle are no better prospects. Mitt Romney is a two-time loser already, and Paul Ryan, although he has not ruled out standing as a candidate at the convention, is not suicidal: trying to unite the party in July, then beat Hillary Clinton in November, would be quite a trick. Ryan resisted even taking up the House speakership, having seen how the party’s congressional schisms brought down Boehner. Would he take a greater risk with a presidential bid?

Movement conservatives and the Republican establishment are stuck together for now, and they’re stuck with Cruz, who represents the only prospective nominee who can claim legitimacy as the alternative to Trump. And however imperfect he might be, Cruz would do more to advance the elite plan to remake the GOP for the 21st century than Trump would—especially if Cruz loses in November. His defeat could then be pinned on his being too conventionally right-wing, too Trump-like himself, and on Trump voters bolting the party. That would give the establishment all the more reason to call for a return to the policies associated with Rubio and the 2012 Republican “autopsy.” The failure of Cruz’s Reagan-vintage conservatism would clear the way for a new kind of right in 2020.

The white working class isn’t extinct yet, however, and Trump represents a radical alternative for the GOP: a 21st-century Nixon strategy. The racial polarization involved in this has been getting plenty of attention, but the economic dimension should not be overlooked. Trump is not only making promises to American workers that by opposing trade deals he’ll keep good jobs in this country, he’s also bidding for votes by refusing to make cuts to popular government programs. From Social Security to federal funding for Planned Parenthood, voters who want tax dollars to provide services are hearing a pitch from Trump. It’s clear enough where this leads: to a Republican Party that bids with the Democrats to offer voters the most benefits. And if the bidding starts among working-class whites, that doesn’t mean that’s where it will end. If the dream of elite Republicans is to win blacks and Hispanics by appealing to values, the Trump strategy may ultimately be to appeal to their economic interests in much the same way as Democrats have traditionally done.

In simple terms, the elite Republican plan is for the GOP to be a multi-ethnic party whose economics are those of the elite itself; the Trump plan is for the GOP to be a party that politically plays ethnic blocs against one another, then bids to bring them together in a winning coalition by offering economic benefits for each group. Neither of these approaches is guaranteed to succeed, of course: non-white voters who already prefer the Democrats may continue to do so despite a liberalization of the GOP’s immigration policies, while the Nixon-Trump strategy risks being outbid by Democrats—who are historically more accustomed to promising government services—and sacrificing a growing number of non-white voters for a shrinking number of working-class whites.

In a healthy party these factions, Trump and anti-Trump, might learn from one another, the anti-Trump side coming to recognize how it has failed the white working class and the need to provide for it once more; the Trump side acknowledging the demographic realities of the 21st century and the toxicity of strident identity politics. Alas, the GOP has shown no capacity at all for learning from the mistakes of the Bush era—the establishment’s support this cycle for another Bush and for the Bush-like Rubio is proof of that—and the same is likely to be true of learning from the Trump crisis, or of Trump learning from the candidates he has vanquished.

Perhaps Cruz might do what the Republican establishment and Donald Trump cannot, reconciling the demands of the white working class with those of burgeoning cohorts of Hispanic and Asian voters. If he hopes to prevent Trump from assembling a delegate majority ahead of the convention, Cruz will have to broaden his appeal beyond the most religious and ideologically orthodox blocs of the GOP. Those very conservative or devoutly evangelical voters have allowed Cruz to win caucuses and closed primaries in some deep-red states, but they cannot counter the sheer mass of voters that Trump brings out in larger and more politically mixed states. For Cruz, broadening his appeal will be no easy thing, when his entire political profile is based on being the most strictly orthodox movement conservative of all. Orthodox conservatism has served white working-class voters poorly, and now that they’ve been offered an alternative by Trump, they’re taking it.

Cruz’s window of opportunity to halt Trump’s progress toward a delegate majority is closing quickly. The Utah caucuses on March 22 give him a shot at another state-wide win, and the Arizona primary that day will put to the test the question of whether John McCain’s home state prefers an orthodox conservative or the very unorthodox Trump. No polls have been taken since last year, but Trump would seem to be the favorite to win Arizona. And after that, the race heads to turf that’s likely to be exceptionally difficult for Cruz: Wisconsin’s primary on May 5, then New York’s on April 19. Unless Kasich can bleed Trump in Wisconsin, the prospect of blowout victories for Trump loom in April.

Trump has overwhelmed all opposition so far on the strength of earned media. The disparity between Trump and Cruz as a ratings draw for cable television will only continue to favor Trump as the race inches onward. Cruz and Kasich risk losing all their media oxygen in the coming weeks, and without that, building momentum to cut into Trump’s winnings will be excruciatingly difficult. Almost as hard as creating a new order out of the chaos of a contested convention. The irony of Cruz’s position is that the party’s future now hinges on how well he can do with an orthodox conservative message drawn from its past.

Voters Don’t Love Rubio the Way Elites Do

Donald Trump appears to have won all 50 delegates in Saturday’s South Carolina Republican primary, but this hasn’t stopped certain pundits from proclaiming Marco Rubio the real story. Rubio took second place with just .2 percent more of the vote than Ted Cruz received. While Cruz was supposed to have an advantage given the state’s large evangelical vote, Rubio had the endorsements of key figures in the state’s political establishment, notably Governor Nikki Haley and Sen. Tim Scott. That Trump beat both of his main rivals anyway, and that neither of those rivals decisively beat the other, is a testament to Trump’s success. This was a tougher test than he’d faced in New Hampshire, and he passed.

Jeb Bush did not—and so he dropped out. In 2000, his brother had used South Carolina as a firewall against John McCain—who had won New Hampshire—by uniting the evangelical and establishment vote behind that year’s Bush. And in 1996, South Carolina helped save Bob Dole from Pat Buchanan—another indication of power of the establishment in the Palmetto State. This year the establishment was divided between Rubio and Bush (who had the endorsement of South Carolina’s other senator, Lindsey Graham). But then the right was divided between Trump and Cruz. (John Kasich and Ben Carson, each of whom received about 7 percent of the vote, also contributed to the fragmentation.)

Cruz has grounds for complaint about the way Rubio has been anointed by the media. Consider: if Rubio had finished .2 percent behind Cruz, instead of .2 percent head of him, would any of the pundits now calling Rubio a winner have changed their tune? The nice thing about being the insiders’ favorite is that it doesn’t matter whether you finish second or third—you’re still on top.

Conventional wisdom now has it that Rubio will vault ahead by soaking up Bush’s support. But wait a minute: what support? If Rubio had received every vote that went to Bush in South Carolina, Trump would still have won. And Bush’s support in South Carolina, where he spent millions and flew in his brother to stump for him, was greatly inflated relative to his support just about anywhere else. In the only February poll of Georgia, one of a dozen states that will vote March 1, Bush was at 3 percent. In Arkansas, he was at 1 percent. Even in Virginia—a swing state where Rubio is within striking distance of Trump—adding Bush’s 4 percent to Rubio’s 22 doesn’t beat Trump’s 28. (And in Virginia, Kasich has been polling ahead of Bush. At least some Bush voters are likely to opt for Kasich over Rubio.)

Rubio is picking up additional donors and endorsements as he becomes the establishment’s consensus choice—but then, all of Bush’s once overwhelming financial backing and his anointment by the establishment and media a year ago didn’t do him much good in the end. (I too thought Bush would be a juggernaut with all that behind him: I was wrong.) Yes, such things are better to have than not to have, as are the votes Rubio will reap from Bush’s departure. But these are marginal gains: they don’t transform the race.

The primaries on March 1, however, really will be transformative, and in complicated ways. Each of the three prime contenders for the nomination—Trump, Cruz, Rubio—will have something to brag about on March 2. Cruz should handily win Texas and ought to have a shot in Oklahoma as well. Rubio can win Minnesota; he’s a plausible candidate for Tim Pawlenty voters, just as he is assuredly the candidate of the Tim Pawlenty pundits who hyped the Gopher State governor’s chances in 2012. Virginia is in play for Rubio, and Colorado as well. Trump faces a new challenge in having to campaign in several places at once—he’s proven he can win states like New Hampshire and states like South Carolina, but can he win Massachusetts and Georgia on the same day, while fighting elsewhere as well? In some of the Super Tuesday contests, the fact that Ben Carson is still in the race may prove more significant than Jeb Bush’s dropping out. If Carson draws large enough percentages of evangelicals, he can make the difference between a Cruz victory or a Trump victory—or in Colorado especially, a Rubio victory against both of them.

Kasich has little chance of winning anywhere on March 1, but a few respectable second- or third-place showings should keep his campaign alive long enough to score its first victory—a delegate-rich one—when Ohio votes on March 15. That same day, Florida will be a make-or-break for Rubio: if he loses to Trump (or Cruz) in his home state, it’s hard to see what his argument is for remaining a viable prospect for the nomination. If Rubio wins Florida, however, he’ll not only have a weighty delegate bloc, he’ll have made a prima facie case for his strength in the general election. Indeed, for all the factiousness of the Republican contest, the fact that the GOP has candidates who may hold special appeal for the battleground states of Ohio and Florida in November must be a source of comfort. And notably, Rubio and Kasich are the Republicans who poll best against Hillary Clinton in hypothetical general-election match-ups.

But it’s a long way yet until November, or even the GOP convention in July. And if Trump has disrupted Republican politics so profoundly—ending, for now, the Bush dynasty and defying all pundits’ expectations—who’s to say he can’t also rip up the playbook in a general election? As for Cruz, he’s the one rival to beat Trump so far, and he’s beaten Rubio more often than not. (Again, imagine how different press coverage would be if Rubio, rather than Cruz, had finished third in New Hampshire.)

After Iowa, I predicted that the Republican establishment, movement conservatives, and a superficial media would concoct a narrative that would help make Rubio the nominee. Just as the Trump phenomenon itself has been media driven, or was at the start, a media-driven Rubio storyline could do wonders for the Florida senator. (The money and organizational resources that come with being the establishment’s pick are also nothing to scoff at, however inadequate they proved to be for Jeb Bush.) Only Rubio’s disastrous debate performance before New Hampshire and his fifth-place finish in that first primary made it impossible to stick to the story.

Now it’s back. And I still think this elite bias in his favor is one of Rubio’s strongest assets. But there’s a difference between acknowledging that hype matters and actually believing it. Based only on the outcomes so far, Trump is the solid frontrunner and Cruz, not Rubio, is his nearest rival. That might change a week from Tuesday, but it’s what voters up to now—not the pundits—have decided.

The End of the Scalia Era

I met Justice Scalia only once. He spoke at Washington University in St. Louis while I was president of the College Republicans there, and I attend a lunch with him and a half-dozen faculty and other students. What stands out in my memory is Scalia’s answer to a professor who asked whether he objected to demographic quotas on the Supreme Court—that is, whether the idea that there now had to be at least one black justice, at least one female justice, etc., was a problem. Scalia cheerfully said it was not, as long as those who filled the quotas were qualified. After all, there had been quotas of other kinds in the past, he noted, such as a requirement that the court should have a distinct Southern representation.

Scalia’s death throws into question another, more important balance on the court, the ideological one. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and all the Republican candidates on stage in South Carolina on Saturday night said that President Obama should not bother trying to nominate anyone to fill Scalia’s vacancy. Let the next president make the appointment, they say, and let this be something voters decide when they choose that president in November. In terms of textbook civics the suggestion is appalling, but the political realities are clear-cut: a Republican Senate—indeed, a Republican judiciary committee—will not grant a lame-duck Democratic president a chance to replace a Republican justice in an election year. The court had a 5-4 Republican majority before Scalia’s death, though the mercurial Anthony Kennedy—Scalia’s fellow Reagan appointee—kept the court from reliably aligning with the Republican right. Even the most moderate Obama appointee would give America the most liberal and Democratic court in 30 years.

Republicans are, of course, taking a risk: should a Democrat be elected as president in November with significant coattails in Senate races, the result would be a much stronger hand for a successor from Obama’s party to play in picking judges. But some Republicans see the risk as a clarifying one—indeed, as something that will unify the party around an electable candidate, one not named Donald Trump. The GOP establishment certainly sees the case for a candidate like Marco Rubio or Jeb Bush strengthened by this turn, while Ted Cruz, the only 2016 aspirant with judicial experience, is banking on it helping him. Trump has so far defied the litmus tests of movement-conservative orthodoxy, but the idea that one must vote for a viable Republican for the sake of getting Supreme Court justices who will re-moralize America and defend free markets through their constitutional jurisprudence remains a knockdown argument for many voters on the right.

No matter what happens, conservatives who hope that Supreme Court appointments will turn the tide of the culture war are apt to be disappointed. Since the brutal Robert Bork hearings, a generation of lawyers aspiring to land on the Supreme Court one day has learned to keep quiet about controversial subjects. That first of all makes identifying reliably right-wing nominees difficult, and it further means that having acquired a habit of avoiding conflict even a right-leaning nominee might not have much spirit for battle once on the court. Certainly it’s hard to imagine any new justice following Scalia’s example as an outspoken cultural combatant. Justice Alito is not quite another Scalia, and future justices promise to be more in the mold of John Roberts.

For this reason, even if movement conservatism enjoys a brief renewal of its consensus in the wake of Scalia’s death, in the long run Scalia will be seen as the last really unifying figure of the postwar American right. Paleoconservatives and right-leaning libertarians, as well as the establishment right, idolized Scalia, and the promise of another Scalia kept them all in the Republican Party—or at least voting for Republican presidents. Scalia was the embodiment of conservative opposition to the liberal jurisprudence of the ’60s and ’70s, and that opposition was the glue that held the conservative movement together over the last 40 years, as the end of the Cold War and the waning electoral power of welfare liberalism attenuated other sources of unity.

Ironically, the best chance the Reagan right might have for gaining a new lease on life, in an era when talk about tax cuts and military build-ups has become passe, could rest with a revival of judicial liberalism. But probably even that would not restore the matrix out of which the Reagan consensus came. War, immigration, trade, and political correctness are the issues that quicken conservatives’ pulses these days, and the Supreme Court is not the left’s driving force in any of them. That could change—but until it does, the right will be more divided by policy differences than unified by a common foe in the judiciary.

Antonin Scalia was a titan of his time. But there are no more Scalias waiting to take the stage, and in the years to come the Supreme Court may not be the stage that matters most.

Should Rand Have Run Like Ron?

Rand Paul’s campaign strategy worked brilliantly—for Ted Cruz. For Rand, it’s led to him dropping out before the first primary. Staunch libertarian supporters of his father’s two campaigns believe Rand should have run more like Ron. But it’s worth examining why he didn’t and why neither Paul has come close to the nomination.

Rand Paul’s team last year seemed to expect a three-way race with Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio, in which a candidate who could unite the right would win. To that end, before the campaign began Paul built ties to the Heritage Foundation—the bastion of movement conservatism—and aggressively courted evangelicals of the sort who ultimately delivered victory to Cruz in Iowa this week.

The Kentucky senator would not campaign, as his father did, as a libertarian insurgent. Instead, Rand would be the total package, the libertarian who was as passionate about Israel as any evangelical, who would restrict immigration just as the party’s grassroots demanded, and who would be a rock-solid Heritage conservative, albeit one for the 21st century. He would not be the candidate of any niche.

Against Bush and Rubio this might have been a winning strategy. But who needed Paul to put on this act when Ted Cruz can do it better? Cruz was a closer fit for the evangelicals, and though Cruz is hated by movement-conservative insiders, he was always better positioned to be an all-purpose right-winger than was Paul, with his libertarian legacy. The mainstream media buzz that made Rand Paul “the most interesting man in politics” didn’t help him with Republican voters, and while newsmakers remain fascinated with the idea of Rand as a new kind of Republican, they’ve found it more effective to cast Marco Rubio for that role simply on account of how he looks. To figure out why Paul is a new sort of Republican requires reading whole paragraphs; to see why Rubio is, just glance at a photo.

Several of the rationales for Rand’s failure have the merit of being true. His team can’t be blamed for overestimating Jeb Bush—everyone did, myself included. And Cruz has proved to be a more adept retail politician than his reputation inside the halls of power suggested he would be.

The rise of ISIS certainly undercut Paul’s foreign-policy appeal, while in domestic policy—unlike his father in 2008 and 2012, Pat Buchanan in the 1990s, or Bernie Sanders among Democrats today—Rand didn’t have an economic position distinct from rivals’. The Kentucky senator was unique in his commitment to civil liberties and reining in domestic surveillance, but those are hardly issues that drive Republicans to the polls. Rand might have snatched the media’s attention from Trump if he’d been the sole Republican (presently in office, that is) to support the Iran deal, and he would have energized more of his father’s base by being more outspokenly anti-interventionist. But how far would that have taken him?

There’s a perfectly good case to be made that this just wasn’t Rand Paul’s year and nothing his campaign did could have made much difference. Even his poor showing in Iowa (fifth) relative to his father’s performance in 2012 (third) has to be kept in perspective: in 2012 the evangelicals’ favorite, who was then Rick Santorum, took first place; the establishment’s favorite, Mitt Romney, took second in a virtual tie. In 2016, those Romney voters were always more likely to go for a Rubio than a Rand Paul, and the evangelicals were always be more apt to go for a Cruz. Even in the best-case scenario, without Donald Trump seizing the anti-establishment vote that went for Ron Paul in 2012, third place would have been about as good as Rand could have expected.

That Ben Carson actually beat Rand for fourth place only underscores the point: Iowa is a state in which the evangelical vote has muscle to spare, and a “libertarian-ish” Republican named Paul is never going to overcome the religious right there. Just because caucuses have smaller turnout than primaries does not mean the proportion of libertarian-ish voters is going to be any more favorable.

Had Rand Paul run another Ron Paul campaign, he might have done better—but not well enough. Campaigns fueled by insurgent enthusiasm have a lousy track-record against even establishment opposition as underwhelming as Bob Dole and Mitt Romney. What would make an insurgency this year—or in 2020, for that matter—any different?

As the Trump phenomenon has shown, there are many more anti-establishment voters than there are libertarian voters. But even anti-establishment voters—perhaps 30 percent of the GOP—are not enough to take the nomination. If Cruz can take Trump down quickly enough, he might yet beat Rubio by combining the religious right with the anti-establishment vote, but considering that Trump is stronger than Cruz almost everywhere, that seems unlikely. (Cruz polls better as a second choice candidate than Trump does, which is one indication that Trump would not benefit as much from Cruz getting sidelined as Cruz would benefit from Trump’s absence.)

All of this is a grim picture for libertarian-leaning Republicans and others who have put their hopes in one or both of the Pauls. A libertarian “fusion” candidate, like Rand Paul this year, is unlikely ever to surpass someone like Cruz who offers a more visceral appeal to non-libertarian right-wingers (religious or hawkish); while an insurgent libertarian, like Ron Paul in 2008 and 2012, is limited to getting more or less the same anti-establishment percentage that goes for a Trump or Buchanan—which has never been enough to beat the establishment.

The one thing neither Ron Paul nor Rand Paul tried is to court the establishment’s own voters—that is, those Republicans who just want a respectable, electable nominee. The problem with this approach is not that libertarianism can’t be respectable or electable; on the contrary, modestly libertarian attitudes can be found quite readily among center-right Republicans. Rather it’s that libertarians are romantics. Right-wing libertarians prefer dreams of populist uprisings or systemic collapse to the unglamorous and frankly dirty work of politics and policy, while center-left and dead-center libertarians tend to be technocratic types who disdain association with conservatives of any stripe. Their fantasy is of a world that keeps naturally getting nicer through guiltless sex and global commerce. Ahh!

America is nowhere near as anti-establishment or anti-statist as right-wing libertarians want it to be, while libertarians unsympathetic to the right are too mild to confront the love of power that in politics trumps the love of money and love of pleasure alike. Right-wing Republicans and left-wing Democrats both have much tougher agendas than non-right libertarians can handle. So those libertarians wind up with no firm allies—despite their hopeless infatuation with the left—while right-wing libertarians have mostly ineffective ones: unpopular populists, for example.

Ron Paul didn’t have illusions about any of this. His campaigns were educational rather than directly political; winning the nomination—let alone the White House—wasn’t the point. That’s not to say his efforts and those of his campaign staff (I was one of them in 2008) weren’t sincere: pushing as hard as possible for the nomination was the best way to advance the educational effort as well. But knowing what the odds against his winning were, Ron Paul fought on because there was always something else to be achieved.

Rand Paul was also clear-eyed: his aims were political, not educational, and the libertarian populism that served his father well would not win Rand—or anyone else—the presidency. So he broadened his brand; unsuccessfully, as it turns out. Movement conservatism is a rigid thing that doesn’t reward the ideologically entrepreneurial qualities that make libertarianism attractive to so many Americans of different backgrounds. A libertarian Republican has many novel views, for a Republican, about civil liberties, foreign policy, armistice in the culture war, and a capitalism that aspires not to be cronyism—all this can open the party to people turned off by the GOP’s presently bellicose brand. (Including younger religious conservatives and disillusioned Eisenhower Republicans.) But evangelical voters and movement conservatives are the Republican constituencies least appreciative of those ideas— less appreciative even than the average Romney or Dole voter.

Rand was right to try to broaden libertarianism’s political appeal, but he was mistaken in trying to become the most orthodox right-winger in the race at the very same time. Rather than trying to combine relatively well-defined and incompatible ideologies—libertarianism, religious rightism, and movement conservatism—a future contender might be better off trying to combine libertarianism with old-fashioned Republican pragmatism, the non-philosophy of the so-called establishment. Rubio shows how the neoconservatives have done this, fusing their stark ideology to an appearance of moderation and electability. Libertarians and reality-based conservatives can do likewise.

This does not mean failing to appeal at all to the more self-consciously right-wing elements in the party. The neoconservatives do, of course, have their own sway with evangelical right. But Bill Kristol never prefers the likes of Mike Huckabee or Rick Santorum as the Republican nominee; the preferred vehicle for neoconservatism is always a respectable, electable one. That’s not because respectability and electability are inherently neoconservative traits—far from it—but rather because neoconservatives are more interested in winning office and shaping policy than they are in proving their right-wing bona fides. They know how the GOP works.

This is heresy, however, to anti-establishment populists, who prefer to lose with their ideological credentials intact rather than win by going mainstream. It’s also heresy to those who want to believe the Republican Party is deeply right-wing and principled rather than confusedly center-right and pragmatic. But the GOP is a national party: it can’t represent only the saved; it has to be a party of the damned, too—whether in religious terms or the mock-religious terms of ideology. It’s a party of sinners, statists, and sellouts just like any other party that actually wins office.

The campaigns of the two Pauls have been learning experiences for libertarians and libertarian-leaning conservatives. Ron Paul built a fundamentally nonpolitical movement, and others—including Rand—channeled its energies into political successes from the local level up to a race for the U.S. Senate. Rand Paul recognized that something more was needed to get to the White House, and he tried a plausible formula that turned out to be more plausible for Cruz than Rand. Another insurgent libertarian campaign won’t achieve anything that Ron Paul’s campaigns didn’t already achieve in 2008 and 2012; and another libertarian effort to be the most orthodox right-winger can be expected to end just like Rand’s. But libertarians and libertarian conservatives have another approach to try, one that co-opts the establishment foe that cannot be beaten by frontal assault. That’s an effort both political and educational, and it requires what for any ideologue is the hardest thing: learning to become the mainstream.

The Establishment Wins With Rubio

Politics is more about organization than raw enthusiasm. Donald Trump was beaten last night by Ted Cruz’s organization in Iowa—and more significantly, they will both be beaten by Marco Rubio’s organization nationally. That’s because Rubio’s organization is not only his campaign but the Republican establishment and conservative movement as well. He can even count on the organized power of the mainstream media aiding him, for while the old media may dislike Republicans in general, they particularly loathe right-wing populist Republicans like Cruz and Trump.

A divided right is the classic set-up for an establishment Republican’s nomination. Cruz and Trump draw upon the same base of voters. Rubio, it’s true, has establishment rivals to finish off in New Hampshire—Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, and John Kasich. But Rubio has been within a few points of Bush and Kasich in recent New Hampshire polls, and after Iowa it’s not hard to imagine him gaining three or four points, probably more, over the next week. Cruz, who hasn’t been far ahead of the moderates in the Granite State, might also gain a few points, but those will most likely come at the expense of Trump, who to be sure has plenty of margin to spare. Although it’s possible that Trump and Cruz will finish first and second in New Hampshire by splitting a big right-wing turnout, Rubio seems to have a good shot at placing second by swiftly becoming the establishment’s unity candidate.

Jeb Bush may hate his fellow Floridian, but Bush has a family—a political dynasty—to think about. The whole family’s political fortunes depend on Republicans, and establishment Republicans at that, winning again. Does Jeb want to be the Bush who turned his party over to Trump or Cruz (hardly beloved by his fellow Texan George W.) and their uncouth supporters, only to lose in November? The family’s rich and influential friends know the score, and they’re on the phone with Jeb right now telling him to get out. His son, George P., will do just fine in a Rubio administration, and who knows, maybe Jeb himself can be ambassador to Mexico.

The story of how Rubio won the establishment’s civil war is the story of just how adroit the neoconservative “deciders” really are. Neoconservatives compounded the George W. Bush administration’s Iraq folly, but because Bush was the brand name attached to the disastrous policies of 2001-2009, the Bush family suffered the consequences far more than did the obscure policy hacks and think-tank propagandists (and their billionaire backers) who egged the administration’s warhawks on. The neoconservatives have turned against the Bush family in part because it’s damaged goods, in part because the Bushes had started to catch on: George W. began to reconnect with foreign-policy realists in his second term, and while Jeb may count Paul Wolfowitz among his advisers, he also consorts with James Baker, anathema to the neocons.

Heading into 2016, neoconservative foreign policy needed a new, untainted brand and a less experienced, more malleable candidate—someone who wouldn’t be as wary as an old Bush might be. In Marco Rubio, everything was ready-made. The fact that Rubio’s brand isn’t foreign-policy failure—the legacy the Bushes must live with—but rather that of a fresh-faced Hispanic, a new and different kind of Republican, meant that the media and public would not guess that what they were in store for was more of what was worst in the George W. Bush administration. As if to taunt the forgetful, the Rubio campaign adopted as its slogan “A New American Century”—counting on no columnist or newscaster to remember the name of the defunct Kristol-Kagan invasion factory. Rubio has been similarly blunt in his hawkish statements throughout the Republican debates.

Conservative realists as well as libertarians are apt to be dismayed by Rand Paul’s fifth-place finish in Iowa, ahead of Bush by roughly two points but behind Ben Carson by nearly five. Ron Paul had finished third in 2012, with 21 percent of the vote compared to his son’s 4.5 percent this year. But anything short of the nomination is only worthwhile as a learning experience and as an opportunity for further organization, and in that regard Paul’s well-wishers need not be discouraged. Though the Republican Party has reverted to a hawkish disposition since 2013, there is still a better-organized counter-neocon faction in the party today than there was in 2003, when the Iraq War began, or even 2006, when Republicans paid the political price for the war. And it’s notable that the top finishers in Iowa, Trump and Cruz, while being far from realists or libertarians, are almost equally far from being neoconservatives. The party’s foreign-policy attitudes are more diverse today than they were even in 2012.

Both libertarians and conservative realists got carried away by their own hopes in the five easy years between 2006 and 2013, when the domestic political climate and world events alike took a favorable turn for realism and made things maximally difficult for neoconservatives and hawks. Today things are hard for everyone—though the hawks and neoconservatives are fortunate in having an avatar like Rubio, whose youth, looks, and race make even those who should know better yearn to give him the benefit of the doubt.

The danger is that libertarians and traditional conservatives will learn the wrong lesson now: the problem is not exactly that Rand Paul was not more like Ron Paul in his unbending libertarianism or more like Trump in his rabble-stiring populism. To be sure, Rand came off as sometimes tentative and embarrassed about his principles, and in trying to appeal to the hawkish evangelical right he only alienated his base while failing to win much new support. But while his father did better in 2012 and Trump did better still this year, neither of them had what it takes to actually win. The insurgent right is extraordinarily bad at politics and consistently mistakes raw enthusiasm for effective electoral power. Ron Paul couldn’t leverage his third-place Iowa finish in 2012 the way Rubio’s allies are set to capitalize on his third-place finish this year because the extra-political as well as political organization that Rubio commands dwarfs anything that the libertarian or populist right possesses, and the neoconservatives have been much more effective at devising narratives and message-frameworks that the mainstream media and the business class can support. Trump might get second place, Ron Paul might get third, yet both remain fringe figures to the opinion-forming classes.

Rather than face this fact, too many true believers on the right prefer to retreat into fantasy—indulging in dreams of third parties or sudden popular uprisings or the triumph of disembodied ideas over mere flesh-and-blood politics. Yet better, more far-sighted organization in politics and the media is the only way to advance worldly change. The neoconservatives have understood this better than anyone.

And so the neoconservatives have won the civil war for the Republican establishment, beating the semi-neocon Bushes and elevating their preferred candidate, Marco Rubio, to the role of establishment savior. The unified neoconservative-establishment bloc now waits for Trump and Cruz to bleed each other dry, before Rubio finishes off whoever remains—probably Cruz. Should all proceed according to plan, the fresh-faced establishment Republican champion then goes to face the haggard old champion of the Democratic establishment, Hillary Clinton, in November. Whoever wins, the cause of peace and limited government loses. Yet even then there will come a backlash, as always before, and next time perhaps an opposition will be better prepared.

Iowa’s Next Santorum-Vote Surprise

Four years ago, Newt Gingrich led national polls of Republican voters, nearly 28 percent of whom indicated they supported the former House speaker. Mitt Romney was close behind at 24 percent, however, and in Iowa polls of prospective caucus-goers suggested that Ron Paul might beat them both—Paul getting 22 percent, Romney 21 percent, Gingrich 14 percent.

The polls were wrong. Gingrich would only win South Carolina and his home state of Georgia. He didn’t even make the top three in Iowa, where Romney and Paul placed second and third—and the surprise victor, who nine days before had been polling behind Rick Perry and Michele Bachmann as well as Paul, Romney, and Gingrich, was Rick Santorum. He, not Gingrich, would be Romney’s toughest competitor for the rest of the campaign, winning 10 more contests after New Hampshire.

This year Donald Trump polls better than Gingrich did in 2012, both nationally and in the early states, and no establishment contender in 2016 has the support that Romney did last time. But Santorum’s 2012 upset might still tell us something about what to expect on February 1. Santorum’s performance showed that Iowa voters were even more focused on social issues than pollsters and pundits had realized. Religious right caucus-goers voted their consciences, and when they asked themselves whether Romney or Gingrich or Ron Paul best represented their views, they disregarded the choices that polls and the media had given them and voted for Santorum instead.