Four environmental reasons why fast-tracking the Carmichael coal mine is a bad idea

Updated

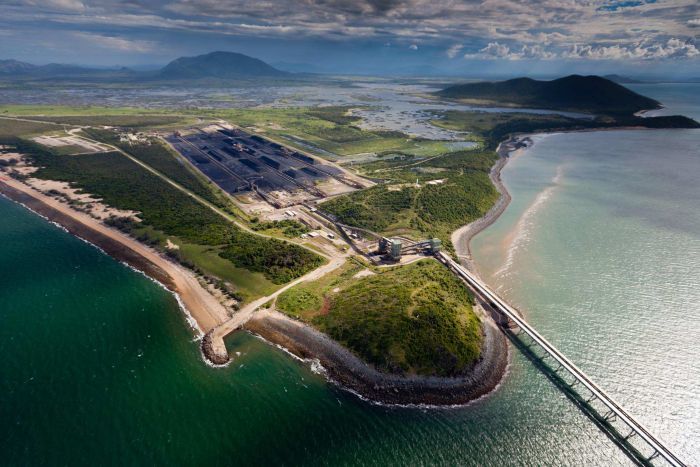

Photo:

Abbot Point port will host the departure of the vast coal reserves of the Galilee Basin. (Supplied)

Photo:

Abbot Point port will host the departure of the vast coal reserves of the Galilee Basin. (Supplied)

Pressure is mounting for Adani's Carmichael coal mine to proceed in inland Queensland. Recently the State Government quietly gave the project "critical infrastructure" status to prioritise its development.

Providing this level of government status to a private enterprise is unusual — the last time it happened was in the early 2000s, and it is usually reserved for projects associated with national security, public education and health.

In response to delays and finance issues, Adani has also reportedly scaled back its initial proposal to increase the mine's viability. There are also growing political calls to weaken the ability of environmental groups to challenge infrastructure projects.

Others have commented on the mine's issues around employment, finance, and Indigenous and rural communities. But as ecologists, there are four good reasons why we believe the mine should not go ahead.

Climate change

To meet the obligations under the Paris climate agreement to limit warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, it is widely accepted that 90 per cent of Australia's coal will need to stay in the ground.

The proposed extraction of 2.3 billion tonnes of coal from the Carmichael mine flies in the face of global efforts to stop climate change.

The emissions from the coal from this one mine would exceed 0.5 per cent of the entire global carbon budget — the total amount of carbon that can be emitted without exceeding 2C warming.

Put another way, the 4.7 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions associated with the mine will be equivalent to nine times Australia's overall emissions in 2014.

Yet these emissions have been given little consideration in the mine's approval process.

Adani's Environmental Impact Statement makes little reference to the mine's "downstream" emissions, and Australia's former environment minister Greg Hunt, in his reasons for approving the mine, said the emissions would be "managed and mitigated through national and international emissions control frameworks", including in those countries that import the coal.

Following an appeal challenging Mr Hunt's assertion that these emissions would have no directly quantifiable impact on the Great Barrier Reef, the Federal Court found the minister was entitled to find that the burning of the coal will have no relevant impact on the reef.

The Great Barrier Reef

The shipping of coal from the Carmichael mine is contingent upon redeveloping the shipping port at Abbot Point, which requires dredging the seabed.

Photo:

Coral bleached white in shallow waters off Lizard Island in the Great Barrier Reef (Supplied: WWF)

Photo:

Coral bleached white in shallow waters off Lizard Island in the Great Barrier Reef (Supplied: WWF)

Following public opposition to dumping dredge spoil at sea, the most recently approved proposal is to dredge 1.1 million cubic metres of the seabed and dump the spoil on land next to the Caley Valley Wetlands.

The wetlands are important habitat for at least 22 migratory shore birds listed under the national environmental legislation, so the current plan is still contentious.

The current plan to dump the dredge spoil on land still won't save the reef because the actual dredging process removes the seabed, along with the seagrass and animals that survive there.

Dredging also releases fine sediments, reducing water quality while smothering surrounding seagrass beds and coral reefs, with some models predicting the spread of fine sediments up to 200km from where the activity took place, within 90 days.

Corals exposed to dredge material are twice as prone to suffer disease. Improving water quality is a key factor for increasing the resilience of coral reefs to major bleaching events.

Water

The Carmichael Mine as currently proposed would extract 12 billion litres of water each year. Removing this water to access the coal seam will reduce water pressure in the aquifer (rock that stores water underground), with knock-on effects. The mine is situated close to the Great Artesian Basin, a key resource for agriculture across inland Australia

For instance, this drawdown could reduce water reaching the Mellaluka and Doongmabulla Springs Complexes, which have exceedingly high conservation value. These springs are some of the largest examples remaining and provide habitat for many species of specialised plants that are only known from spring-fed wetlands.

If the springs go dry, even temporarily, endemic species will not survive and will become extinct at the site.

Removing groundwater is expected to increase the duration of zero- or low-flow periods in the Carmichael River system. The communities and ecosystems in the region are already highly reliant on groundwater, due to variable surface waters. This could also affect the acidity and salinity of soils.

Photo:

The Alpha Coal Project in Queensland's Galilee coal basin. The Carmichael project is the second to be approved in the region. (Commons: Lock the Gate Alliance)

Photo:

The Alpha Coal Project in Queensland's Galilee coal basin. The Carmichael project is the second to be approved in the region. (Commons: Lock the Gate Alliance)

Clearing the land for the mine itself — an area equivalent to Queensland's Moreton Island — will likely reduce local rainfall considerably.

Due to the high uncertainty surrounding groundwater, the independent scientific committee recommended improvements in groundwater modelling and monitoring before proceeding with the project. The high degree of uncertainty and inadequate treatment of groundwater impacts in the Environmental Impact Statement were the subject of legal proceedings in the Land Court in 2015.

Threatened species

The Carmichael mine site is home to the largest known population of the endangered southern Black-throated finch (Poephila cincta cincta), which has lost 80 per cent of its former habitat.

The intact areas of continuous habitat in this region — such as that at the mine site — have so far remained in good condition and relatively free of the invasive weed species that are contributing to the finch's decline in other parts of its range.

The Black-throated Finch Recovery Team highlighted their concern over the Carmichael development with state and federal agencies.

Photo:

Conservationists have expressed concerns over the mine's impact on the black-throated finch. (Supplied: Eric Vanderduys)

Photo:

Conservationists have expressed concerns over the mine's impact on the black-throated finch. (Supplied: Eric Vanderduys)

Adani has proposed to offset the loss of finch habitat resulting from the mine by protecting alternative, nearby habitat. But losing the best remaining habitat means the most viable population will be compromised. Experts have warned that offsetting the loss of habitat from mine development will not avoid serious detrimental impacts on the finch.

Keeping this habitat intact, continuous and un-fragmented will be key to maintaining its suitability for the finch. The only way to avoid severely impacting the finch is to avoid destroying its high-quality habitat — which would mean not digging the mine in these areas.

A brighter future

Giving the mine "critical infrastructure" status allows special dispensations to ignore normal approval processes. And this decision sends a signal to the wider community that this type of short-term thinking is front and centre in the State Government's mind.

Given the clear environmental impacts this mine will have, not just for the region but for the whole planet, we question the effectiveness of Australia's current environmental laws that have allowed it to be approved.

We believe it is time to place the entire social and environmental costs and benefits of this mine on the public table, and ask the question of the politicians who are meant to make decisions in our best interest: is the short-term profit of selling some coal worth it?

April Reside is a researcher in the Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science; Bonnie Mappin is a PhD candidate in Conservation Science; James Watson is an Associate Professor; and Sarah Chapman and Stephen Kearney are PhD candidates, all at the University of Queensland.

This article was written with the help of Claire Stewart and Courtney Jackson, students in the Masters of Conservation Science program and members of the Green Fire Science Lab at UQ.

Originally published in The Conversation.

Topics: coal, mining-industry, mining-environmental-issues, mining-rural, federal---state-issues, qld, mackay-4740, whitsundays-4802, bowen-4805

First posted