Introduction

A few years ago, I wrote about an interesting phenomenon called zoopharmacognosy. The idea is that animals might select specific plants or other substances to eat that would have therapeutic effects. An example might be an herbivore with a heavy parasite load eating a plant it doesn’t normally use as food but which happens to reduce the number of those parasites. It’s a popular idea among proponents of herbal medicine and folks who think the word “natural” is a meaningful guide to effective medical treatment because it reinforces their existing beliefs. However, the reality is a lot more complicated than such people seem able to admit.

There is some evidence that animals in the wild sometimes select plants to eat that might have health benefits. The best evidence comes from insects and other species with short generation times that produce large numbers of young and have rather simple, predominantly genetically determined behavior. Evolution can quickly select for changes in behavior that have a selective advantage in such species because small changes can readily spread if they give even a little advantage to a few individuals, and behavior is not very flexible or complex and so can be altered by small genetic changes.

There is much less reason to think zoopharmacognosy is a common or effective behavior found in more complex species, such as mammals. Most of the claims for this are simply uncontrolled observations with lots of assumptions and bias built in. And proponents of this idea generally ignore the fact that the availability of potentially medicinal plants is unpredictable, their composition and effects vary from plant to plant, region to region, and year to year, that we don’t have actual evidence for the real value of most plants considered “medicinal” by various folk medicine traditions, and finally that wild animals poison themselves or ingest non-food objects with deleterious consequences, which argues against a strong and reliable intuition about what is healthful.

Nevertheless, it should come as no surprise that not only do some alternative medicine proponents claim that zoopharmacognosy is an established and widespread phenomenon, rather than an interesting and largely unproven idea, they also use it to validate other ideas that are just as unproven and often even less plausible. Sadly, some even manage to profit from selling the idea, and a host of bogus remedies based on it, to pet owners. One such person is Caroline Ingraham, the proprietor of the grandly named Ingraham Academy of Applied Zoopharmacognosy.

Applied Zoopharmacognosy?

Somehow, Ms. Ingraham has created an apparently successful business selling the idea that your pet somehow knows which “natural medicine” they need for any illness and that she can teach you how to figure out which remedy your pet wants you to give him or her. According to her mission statement:

The Ingraham Academy of Zoopharmacognosy, headed by the founder of Applied Zoopharmacognosy Caroline Ingraham, promotes self-medication as a necessary component of domestic animal health and trains individuals in how to enable and recognize self-medicative behaviour in animals.

Since it is not at all clear that zoopharmacognosy is a real or significant phenomenon among wild or domestic animals, claiming to teach people how to take advantage of it as a “necessary” part of their animals’ care is quite a stretch.

Who is Caroline Ingraham?

Ms. Ingraham does not provide a great deal of information about her background on her web site. While I think her claims should stand (or more likely fall) on the basis of the evidence rather than her credentials, I think it fair to ask whether she has any formal scientific training experience that might explain how she came to develop this questionable approach to veterinary medicine. Unfortunately, all that is available on her web site is this:

Caroline Ingraham founded Applied Zoopharmacognosy and is the leading expert in this field of animal self-medication…. Caroline has featured in many scientific journals and articles, and has written numerous books on the subject.

At 22 years of age, Caroline studied the clinical use of essential oils for humans with one of the world’s leading experts in aromatherapy, Robert Tisserand and during her studies began to develop her approach towards helping animals using essential oils and other plant and mineral remedies. She later went on to study the French approach to the scientific use of essential oils with EORC (France) and Biologist Thomas Ingraham.

Her work encompasses an understanding of pharmacokinetics and pharmacology combined with animal self-medication.

Given that “aromatherapy” is a dubious practice and there is little evidence for any benefits that are not psychological in nature, studying with “experts” in this field is not a credential that carries much weight. And while she has written a number of books about aromatherapy and her invented field of “applied zoopharmacognosy,” I have not yet found any reputable scientific publications from her on these subjects, despite the claim of being “featured in many scientific journals.”

“Medicinal” Plants?

In addition to classes and books Ms. Ingraham happens to sell the remedies she suggests you let you pet choose among. These include essential oils and a range of plant-based products in various forms. Which raises the first of many problems with Ms. Ingraham’s claims: What are the “medicines” are we supposed to offer our pets?

There is no evidence for any meaningful medicinal value to the vast majority of the products that she sells. There is weak evidence for beneficial effects on subjective mood states, such as anxiety, in humans, but the notion that they can influence the outcome of serious diseases is entirely unproven and highly implausible. (1, 2, 3, 4).

And as I have discussed extensively before, herbal medicine is a complex subject, but the bottom line is there is no herbal product proven to have meaningful benefits for serious disease in companion animals. Most herbal products are untested and unreliable in terms of constituents. And there are serious risks to using untested and unregulated plant-based medicines. So whether or not your pet knows what they need to get better and can tell you, how is it helpful to offer them a selection of remedies that haven’t been shown to actually work?

Of course, the underlying reason for this is far more pragmatic. Not being a veterinarian, Ms. Ingraham cannot employ most medicines that have actually been proven to work. And even the “Founder of Applied Zoopharmacognosy” would likely admit that offering a selection of antibiotics, cancer drugs, pain relievers, and so on and letting your pet decide which drug it needed and how much to take would likely not result in a desirable outcome. That would demonstrate real trust in their inherent wisdom!

Undoubtedly, she would claim that this is different from what she recommends because pharmaceutical medicines are “chemicals” and are not “natural” so the inherent wisdom of animals to self-heal doesn’t operate with such remedies. That’s not a convincing argument, especially given that we at least we know the risks and benefits of real medicines, and feeding our pets her essential oils and ground-up leaves is just playing roulette with untested chemicals.

How Our Pets Communicate their Choices

The method by which Ms. Ingraham suggests our pets can indicate their choice of “remedy” is another problem with her approach. Even if our pets have a preference that is meaningful and appropriate (which has not been demonstrated), it is naïve to imagine that we can read our pets body language with a level of specificity that we can tell which remedy that want without introducing our own bias or influencing their behavior. Studies of drug detection dogs have shown that dogs are very sensitive to human expectations and will often misidentify substances they are supposed to search for when their handler has a pre-existing and incorrect belief about where drugs are located. And the caregiver placebo effect is a well-known phenomenon in which owners and veterinarians see what they hope or expect to see in their dogs rather that accurately observing their behavior.

So what cues does Ms. Ingraham suggest we look for in reading our dogs’ choices? Without buying her book or taking her class (and yes, I know her defenders will say I should do so before evaluating the method, so here is where you can find my prior explanations for why this is not a useful or legitimate argument), I was able to find some of her recommended cues on the site where she sells her products:

Positive reactions:

- Sniffing

- Smelling

- Stillness

- A vacant look

- Blinking

- Stretching

- Closing the eyes

- Lowering the head or lying down

- The work is all about not rushing, and closely observing your dog.

Positive reactions mistaken for negative reactions:

- Grimacing (helps open the vomeronasal organ)

- Barking or lunging at the extract Anxious (behaviour usually signifies a release, followed by calm)

- Jumping away quickly, or backing away from the aroma (usually indicates releasing an unpleasant memory)

Negative reaction:

Lack of interest, or distracted

This list has all the specificity of a horoscope or a homeopathic proving. A lack of interest is a negative sign, but a vacant look is a positive sign. Lunging at the remedy indicates selection, but so does backing away from the remedy. Even blinking is supposed to be a positive sign! Clearly, this is a perfect example of the use of vagueness to allow any interpretation the person making the claim desires to be supported. It is exactly the sort of self-deluding approach to animal behavior that lets pet psychics and their clients convince themselves that bit of magical nonsense is real.

What About Eating Socks?

Of course, any claim that our pets know what’s good for them and choose to eat the healthiest food or most appropriate medicinal plants has to consider the inevitable question of why, if they are so wise, do our animal companions try to kill themselves by eating socks, batteries, massive overdoses of medication, their own feces and vomit, and any number of other distinctly unhealthful substances?

Ms. Ingraham’s response to this question also strikes me as pretty unconvincing. Basically, she claims that our animals may be too hungry to resist toxic plants, that they are fooled by “artificial” chemicals or other substances, such as sugar and flavorings, into thinking unhealthy substances are good for them, or that in nature they would eat a natural “antidote” to a toxic plant after eating that pant but that they don’t always have access to such anecdotes in captivity. None of this reasoning makes much sense, and it ignores both the self-destructive ingestive behavior seen in wild animals as well as the impact of domestication on the physiology, diet, and behavior of many animals, such as dogs and livestock.

What’s the Harm?

There are a number of ways in which the idea of “applied zoopharmacognosy” can be harmful to our pets. For one, the remedies Ms. Ingraham recommends are largely untested, and this means not only that they might not be helpful but that we can’t assume they are safe. As I’ve pointed out many times, plant-based chemicals can do plenty of direct harm.

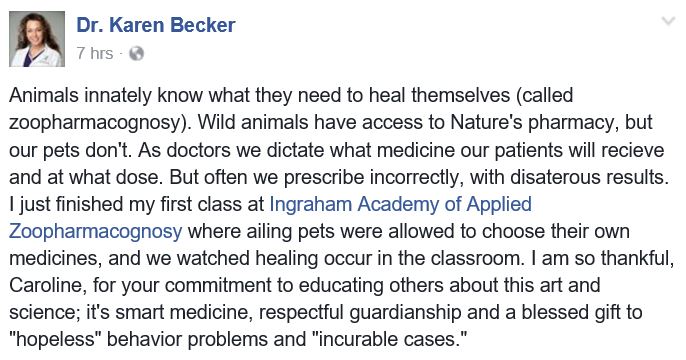

Perhaps the greater risk is the indirect harm caused by relying on nonsense instead of seeking legitimate medical treatment. This is exacerbated by suggesting that this method at be more reliable than conventional medicine, as the ever-unreliable alternative medicine advocate Dr. Karen Becker has done.

To suggest doctors often choose the wrong remedy whereas pets intuitively do a better job when selecting from untested and unregulated alternative products is irresponsible and misleading. And Dr. Becker seems to be forgetting that “wild animals” live shorter lives far richer in parasitism, disease, and suffering than our pets, despite their freedom from misguided doctors and access to “Nature’s pharmacy.”

The following testimonial is a particularly chilling example of how dangerous this sort of delusion can be. A student of Ms. Ingraham describes her use of the nonsense she was taught to treat what she had good reason to believe was a potentially life-threatening illness.

The fact that the owner got away with this response to what might have been a deadly illness does not justify it. The fact that Ms. Ingraham has chosen to post this testimonial on her Facebook page as part of the process of advertising her services suggests she may recommend or approve of using her method and her products in place of proper veterinary care, even in potentially life-threatening situations. That is certainly the impression her student acquired in her class. If this is true, it is a dangerous and irresponsible practice.

Bottom Line

There is little evidence that selection of medicinal plants or other substances by animals in their natural habitat or by domesticated animals is a common behavior with substantial health benefits. Zoopharmacognosy is an interesting phenomenon, but there is very limited evidence for it in most species. Wild animals are generally less healthy and shorter-lived than domesticated animals provided conventional healthcare, nutrition, sanitation, and other basic husbandry, so the concept Ms. Ingraham is selling is mostly a variety of the appeal to nature fallacy.

There is also virtually no evidence that the use of essential oils or many of the plant extracts Ms. Ingraham sells is safe or effective for any serious health condition. Aromatherapy has not been shown even in humans to have significant health benefits, though there may be some mild psychological effects, and in veterinary species there is no reason to think essential oils can dramatically improve health. Likewise, while herbal medicine is a bit more plausible and promising in some ways, it has largely failed to prove its worth in controlled scientific research, and most of the herbal and other plant remedies Ms. Ingraham sells and recommends have not been proven to have value or even to be reliably safe.

The process of letting our pets “select” a remedy is subjective and deeply vulnerable to bias and caregiver placebo effects.

Most importantly, Applied Zoopharmacognosy is yet another unproven and implausible practice that places pets in danger when it is used as a substitute for real veterinary care. Even if the remedies themselves are harmless, which is not certain, the example above illustrates how it can be very dangerous if people are led to believe that these methods and products can replace appropriate medical care.