A piece I wrote for the Gwangju Folly project, curated by Nikolaus Hirsch, Philipp Misselwitz and Eui Young Chun featuring Ai Weiwei, Do Ho Suh, Eyal Weizman, Raqs Media Collective, David Adjaye, Rem Koolhaas and more. The catalogue is available here

Off-season, the Scheveningen boardwalk is a very lonely place. All of its seaside resort jollity is blasted by North Sea winds leaving desolate prospects. Even the blow-up gorilla sitting astride the roof of a fun pub seems to hum, “Come Armageddon, come,” and the giant neon parrot at the end of the pier looks like it would rather be blinking in a neon jungle far, far away.

From the miasma of blur-grey sea mist, a startling figure pulls into focus. Bright and so full of verve, it seems to bound towards us, despite its rigid figure. “Hi!” it says without speaking, “I’m a cone full of chips.” Face bursting with excitement, perky legs sprout from its carton body, chips poking up for hair. One arm is raised in greeting while the other reaches up to the top of its head – no doubt feeling for a chip. Its eyes bulge in anticipation of the taste of fried potato. In fact, so much pleasure emanates from this figure that it seems deliriously innocent of its own imminent self-cannibalism. Its mouth hung open, its tongue swells, lolls out, its teeth are all arrayed in preparation to chomp down on its own body. Ecstatic about its own deliciousness, totally absorbed in its self-ingestion.

The demented fellow seems a poor encouragement for fried food. Its body without organs instead seems to carry another message.

It smiles at us with a knowing smile. “Don’t we all eat ourselves?” it seems to say. “Don’t you, like me, swallow yourself up in self-absorbed pleasure?” Standing as a glowing embodiment of consumption, it is even a symbol of consumption devouring itself.

And while it says these things, it offers a hole in its hollow body as a receptacle for our trash. Just like Brett Anderson, it offers us some kind of redemptive consolation in its (and by extension, our own) lowliness: “We’re tra-a-ash, you and me.”

We encounter these kinds of fiberglass follies in streets, parks, and other touristic locations, the kinds of places wrapped up in absent-minded consumerism. They might be giant sculpted ice creams the size of an adolescent, whipped tops dripping with sauce, their cones sculpted into an exaggerated waffled texture. Or neon pizza slices, each neon mushroom a swiggle of calligraphy. But they aren’t quite signs. They don’t explicitly encourage us to buy, they don’t offer us deals. They remain wordless objects in the landscape. Stupid objects in the stupidest parts of our modern landscape. Not so much advertisements but desire made GRP real, popped as much out of our greedy minds as from the moulds that form them. These are objects of the shallow imagination, idiotic follies of an animal desire for fat, sugar, and flavorings. But they are follies, nonetheless. And as follies they spring from a grand tradition.

Illustration from Erasmus' In Praise of Folly by Hans Holbein

According to Erasmus of Rotterdam, Folly was born to the young and intoxicated god Plutus and “the loveliest of all the nymphs and the gayest” Youth. Folly was nursed by Drunkenness and Ignorance. Her followers include Self-love, Pleasure, Flattery, and Sound Sleep. We might not know much about Renaissance culture or the Catholic Church in the 15th century that Erasmus was apparently addressing, but those character traits sound very familiar, the very same things we wring our own hands about. Erasmus’s text, In Praise of Folly (1511), might be a piece of 500-year-old esoterica but it might help us understand the contemporary significance of a self-devouring bag of chips. Erasmus mobilizes Folly as a form of sarcasm, as a voice able to say things that we can’t say in our own voice. Like the court jester, Folly performs an exceptional role. Its idiocy grants it license to speak the kinds of truths others can’t. Our friendly bag of chips is Folly herself. It talks in Folly’s voice directly to our own self-love, our own empty, trash-filled hearts, and it does so with Folly’s goofy grin and goggley eyes of idiocy.

Adof Loos, Mausoleum for Max Dvorak, (1921)

According to Adolf Loos, “Only a very small part of architecture belongs to art: the tomb and the monument. Everything else that fulfills a function is to be excluded from the domain of art.” Follies too are architecture eviscerated of practical function. Perhaps this makes them art as well. All three forms of construction share a single characteristic: their primary purpose is to embody, transmit, and represent an idea, to petrify narrative into stone or fiberglass. Aren’t tombs just follies minus the fun? And monuments are surely just joyless follies of state. That also means that follies are far more than simple entertainment. They may be playful, but their playfulness is as serious as the grave.

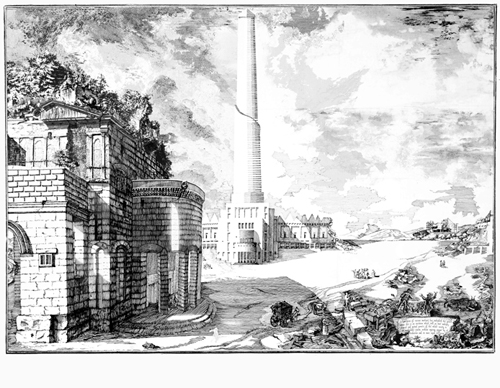

We can trace the architectural folly’s role as idea-made-real to its origins in the 16th and 17th century. Follies operated as decorative objects in the aristocratic landscape that acted as tangible symbols for ideas and ideals. Often taking the antiquated form of Egyptian structures, Greek temples, ruined gothic abbeys, and so on, they summoned up cultural references to make them stony flesh. By summoning up idealized cultural images, they made the imaginary world of their builders real. Follies are equal parts thing and idea, bound together in a way that is impossible to untangle.

Temple of Ancient Virtue, Stowe

Nowhere is this compound of ideology and folly more fulfilled than Stowe, the family seat of the Temple-Granvilles. Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham, was both a soldier and a politician who acted as a mentor to William Pitt. Disillusioned with active politics he retired and took to redesigning Stowe’s gardens. Rather than a retreat from ideology though, the gardens became a vehicle for his political concerns. The very ground was ploughed and reshaped by his political beliefs. Designed with Capability Brown and John Vanbrugh, Stowe was choreographed as a landscaped manifesto, as satire and as a legible political proposition. Structures such as the Temple of Ancient Virtue embodied those virtues Viscount Cobham saw as lacking in his political opponents, while the Temple of Friendship was dedicated to his group of opposition Whigs. The Temple of British Worthies set out an agenda of good and honorable qualities through its selection of poets, philosophers, scientists, monarchs, statesmen, and soldiers. We can read Stowe as a 400-acre ideologically narrative landscape.

Of course, we don’t build landscapes like Stowe anymore. But we do build follies, even if we call them something else. Even if they are simply giant GRP ice creams. And when we do, consciously or not, we also cite the cultural heritage of the folly. In its ridiculous stupidity it operates like Erasmus’s Folly, as the voice of a deranged self-indulgent truth. In its uselessness, it gains Adolf Loos’s amplified essentiality. In its figural representation, it gains Stowe’s narrative ability.

Follies then, whether we like it or not, are serious, sarcastic, and ideological manifestations. The more stupid they are, the more serious they become. The more facile, the clearer their ideology. Follies are ourselves reflected back at us in a magnifying mirror. They are our desires and dreams, our logic and reason made friendly-grotesque, hanging out on street corners ready to wink at us knowingly and smile with that gurning expression of self-recognition.