There is, I’ve come to realise, a certain type of hypocrisy that occurs when eloquent, successful practitioners of reflexive self-defence neglect to consider the consistency of their arguments. It’s a tactic which relies in large part on those arguments not being written down or otherwise recorded: it’s much harder to establish that your interlocutor is contradicting a prior claim if they’ve never made it to your face, or if no handy verbatim record exists, and especially if they deny ever having said it. Your memory must be to blame, or else your comprehension: either way, they’re in the right, and will doubtless continue to be so.

Unless, of course, a transcript is produced.

Lionel Shriver is not an author whose books I’ve ever read for the same reason that I’ve never subjected myself to Jonathan Franzen: the woes of modern day, middle class white people is a genre in which I have little to no interest. It’s nothing personal, except inasmuch as I am myself a modern day, middle class white person – I’d just rather read about literally anything else. So sue me: I’m a fantasist, and always have been, and always will be. But I’m also a writer, and though I have no interest in reading modern literary fiction, its ubiquity and prestige – to say nothing of the many complex issues facing all writers and their communities, regardless of creed or genre – ensures that I still have a dog in its various fights.

Such as, for instance, Lionel Shriver’s recent keynote speech at the Brisbane Writers Festival, the full transcript of which has just been published online.

You see where I’m going with this.

If I wanted to give myself a tension headache, I could waste several hours of my evening going through the dreadful bulk of it line by line and pointing out the various strawmen: the information purposely elided here, the conflation of the trivial and the serious there, the overall privileged rudeness of taking a valuable platform given you for a stated purpose and turning it to another. But what really stands out to me is the utter dissonance between Shriver’s two key arguments, and the bigotry that dissonance reveals: on the one hand, fury at the very idea of “cultural appropriation”, which Shriver sees as a pox on artistic freedom; on the other, her lamentation of particular types of diversity as “tokenistic”.

Early in her speech, Shriver says:

I am hopeful that the concept of “cultural appropriation” is a passing fad: people with different backgrounds rubbing up against each other and exchanging ideas and practices is self-evidently one of the most productive, fascinating aspects of modern urban life.

But this latest and little absurd no-no is part of a larger climate of super-sensitivity, giving rise to proliferating prohibitions supposedly in the interest of social justice that constrain fiction writers and prospectively makes our work impossible.

And yet, mere paragraphs later, we get this:

My most recent novel The Mandibles was taken to task by one reviewer for addressing an America that is “straight and white”. It happens that this is a multigenerational family saga – about a white family. I wasn’t instinctively inclined to insert a transvestite or bisexual, with issues that might distract from my central subject matter of apocalyptic economics. Yet the implication of this criticism is that we novelists need to plug in representatives of a variety of groups in our cast of characters, as if filling out the entering class of freshmen at a university with strict diversity requirements.

You do indeed see just this brand of tokenism in television. There was a point in the latter 1990s at which suddenly every sitcom and drama in sight had to have a gay or lesbian character or couple. That was good news as a voucher of the success of the gay rights movement, but it still grew a bit tiresome: look at us, our show is so hip, one of the characters is homosexual!

We’re now going through the same fashionable exercise in relation to the transgender characters in series like Transparent and Orange is the New Black.

Fine. But I still would like to reserve the right as a novelist to use only the characters that pertain to my story.

I’d ask Lionel Shriver to explain to me how the presence of queer characters can “distract from the central subject matter”, but I don’t need to: the answer is right there in the construction of her statement. Queerness can distract from the central subject matter because, to an obliviously straight writer like Shriver, queerness is only ever present as another type of subject matter, never as a background detail or a simple normative human variation. Straightness doesn’t distract her, because it’s held to be thematically neutral, an assumed default. But put a queer character in the story for reasons other than to discuss their queerness – include them for variety, for honesty, because the world just looks like that – and it’s a tiresome, tokenistic attempt to be “hip” or “fashionable”. In Shriver’s world, such non-default characters can only “pertain to [the] story” if the story is, to whatever extent, about their identity. The idea that it might simply be about them does not compute.

And thus does Shriver bring us that most withered chestnut, Damned If You Do And Damned If You Don’t – or, as she puts it:

At the same time that we’re to write about only the few toys that landed in our playpen, we’re also upbraided for failing to portray in our fiction a population that is sufficiently various…

We have to tend our own gardens, and only write about ourselves or people just like us because we mustn’t pilfer others’ experience, or we have to people our cast like an I’d like to teach the world to sing Coca-Cola advert?

Listen, Lionel. Let me explain you a thing.

Identity informs personhood, but personhood is not synonymous with identity. By treating particular identities as “subject matter”instead of facets of personhood – by claiming that queer characters can “distract” from a central story, as though queerness is only ever a focus, and not a fact – you’re acting as though the actual living people with those identities have no value, presence or personhood beyond them. But neither can you construct a tangible personhood without giving thought to the character’s identity; without acknowledging that particular identities exist within their own contexts, and that these contexts will shift and change depending on various factors, many of which will likely exceed your personal experience. This is what we in the writing business call doing the fucking research, which concept astonishingly doesn’t apply only to looking up property values, Googling the Large Hadron Collider and working out average summer temperatures in Maine.

To put it simply, what Shriver and others are angry about isn’t the nebulous threat of “restrictions [being placed] on what belongs to us” – it’s the prospect of being fact-checked about details they assumed could be fictionalised entirely, despite being about real things.

If Shriver, in a fit of crass commercialism, were ever to write a forensics-heavy crime procedural without doing any research whatsoever into actual forensic pathology, readers and critics who noticed the lapse would be entirely justified in criticising it. If she took the extra step of marketing the book as a riveting insight into the lives of real forensic pathologists, however – if the validity of what she’d written was held up as a selling point, a definitive glimpse into the lives of real people as expressed through the milieu of fiction – then actual forensic pathologists would certainly be within their rights to heap scorn on her book, to say nothing of feeling insulted. None of which would prevent this hypothetical book from being technically well-written or neatly characterised otherwise, of course; it might well have a cracker of a plot. But when you get a thing wrong – when you misrepresent a concept or experience that actually exists, such that people with greater personal knowledge of or investment in the material can point out why it doesn’t work – you’re going to hear about it.

That is how criticism works. It always has done, and always will do, and I am absolutely baffled that a grown adult like Shriver, who presumably accepts the inevitability of every other aspect of her writing being put under the twin lenses of subjective opinion and objective knowledge, thinks this one specific element should be somehow immune from external judgement.

Except that, somehow, she does – and I’ll come to more of that later. But first, there’s an even bigger problem: namely, that Lionel Shriver doesn’t think identities exist at all.

Membership of a larger group is not an identity. Being Asian is not an identity. Being gay is not an identity. Being deaf, blind, or wheelchair-bound is not an identity, nor is being economically deprived. I reviewed a novel recently that I had regretfully to give a thumbs-down, though it was terribly well intended; its heart was in the right place. But in relating the Chinese immigrant experience in America, the author put forward characters that were mostly Chinese. That is, that’s sort of all they were: Chinese. Which isn’t enough.

That distant thunking sound you hear is me banging my head repeatedly on the nearest hard surface. Look, I hate to be That Guy and pull the dictionary definition card, not least because I’m not a linguistic prescriptivist: usage comes first, and all that. But there’s a difference between asserting that a word should only be used a particular way and claiming, flat out, that it literally doesn’t mean the thing it (both functionally and definitionally) means. And to quote our good friends at Merriam-Webster, ‘identity’ means, among other things, “the qualities, beliefs, etc., that make a particular person or group different from others; the relation established by psychological identification”, with ‘identification’ further defined as “psychological orientation of the self in regard to something (as a person or group) with a resulting feeling of close emotional association.”

In other words, being Asian doesn’t magically cease to be an identity just because Lionel Shriver says so. Nor does queerness. Nor does disability. An identity is a thing you claim and feel for yourself, in association with a particular concept or shared bond with others. That being so, what I suspect Shriver is groping after with this blatant misuse of language is the idea that there’s no such thing as a universal identity – that there’s no one way to be female or gay or Armenian, which is correct, and that good characters must, therefore, be more than just a superficial depiction of these things.

Well, yes. Obviously. (Though rather ironically, given her earlier thoughts on queerness.) But saying that there is no universal Chinese experience, and thus no universal Chinese identity, does not ipso facto prove that there is no such thing as any Chinese identity – or identities, as the case may be – at all. Think of it like a Venn diagram: every circle represents the particular experience of belonging to a given group or identity. The point of commonality is that they all overlap; the point of difference is that everyone experiences that overlap differently. You might as well argue that being Christian isn’t an identity because Orthodox Catholics and Southern Baptists both exist. But that’s the macro perspective, where group nomenclature is more taxonomy than experience. Identity is the micro level: the intimacy of self-expression coupled with the immediacy of belonging. And in between those two things, tasked with the perennial balancing act, is the seedy, ever-shifting vagueness problem of group politics: who has authority, who belongs, who doesn’t belong, and why.

But of course, despite her protestations to the contrary, Lionel Shriver does believe in identity. How else can you categorise her prior defence of her own book, The Mandibles, as being “a multigenerational family saga – about a white family,” a narrative in which she “wasn’t instinctively inclined to insert a transvestite or bisexual [character]”? By her own admission, whiteness is an identity, just as straightness is an identity, distinct from their respective alternatives and made meaningful by the difference. But this is an uncomfortable thing for Shriver to admit in those terms, because it means acknowledging that identity is neither the intrusive hallmark of political correctness nor an exotic coat to be borrowed, but a basic fact of human life that applies equally to everyone. What Shriver views as a neutral default is merely a combination of identities so common that we’ve stopped pretending they matter.

Which they do, by the way. They really, really do.

Returning, then, to the subject of criticism, Shriver says:

Thus in the world of identity politics, fiction writers better be careful. If we do choose to import representatives of protected groups, special rules apply. If a character happens to be black, they have to be treated with kid gloves, and never be placed in scenes that, taken out of context, might seem disrespectful. But that’s no way to write. The burden is too great, the self-examination paralysing. The natural result of that kind of criticism in the Post is that next time I don’t use any black characters, lest they do or say anything that is short of perfectly admirable and lovely.

You heard it here first, folks: the burden and self-examination required to be respectful to others – the same thing we ask of any child who borrows a toy at a birthday party – is simply too great for precocious adult genius to bear. And note, please, the telling differences in Shriver’s response to criticism of different aspects of the same novel, The Mandibles: when one reviewer critiques her portrayal of her lone black character, she threatens to be put off writing black characters for life; but when another reviewer rebukes her for writing an overwhelmingly “straight and white” novel, there is no similar threat to disavow writing white characters. But of course, she could hardly threaten to stop writing both – if she did, there’d be nobody left. (Not least because, in Shriver’s world, ‘Asian’ isn’t a real identity. Perhaps she should let Pauline Hanson know; I’m sure her relief would be palpable.)

When Shriver decries identity, she applies the concept only to those identities she doesn’t share, or which she views facetiously, the better to paint it as an arbitrary barrier between her artistic license and the great, heaving soup of Other People’s Stories to which she, by virtue of her personal rejection of the concept of identity, feels entitled. But ask why her writing focuses predominantly on a particular type of person, and suddenly identity is a rigid defence: the characters had to be this way, could never have had some other, more distracting type of identity, because the story was about this experience in particular. Which is to say, about a fucking identity.

Here is the paradox Shriver cannot reconcile, because it’s no paradox at all: if identity is irrelevant and the full spectrum of humanity is rightfully accessible to every writer at any time, then there’s no earthly reason why a multi-generational family saga shouldn’t have queer people in it, and no intelligent way to argue that it can’t. But if, despite the apparent irrelevance of identity and the presence of a full spectrum of humanity about which to write, you’re still predominantly writing about straight middle class white people, we’re liable to wonder what particular biases of culture or inspiration are skewing you that way. That’s not Damned If You Do And Damned If You Don’t – it’s just common sense.

There’s more to this argument, of course – most pertinently, the fact that certain writers occupy a position of greater cultural and historical privilege than others (something of which Shriver herself is well aware). When such writers decide to speak for and about more marginalised groups, that has a material impact on the ability of those groups to speak for themselves and to be heard, especially if their personal accounts differ, as they invariably do, from those of more prominent outsiders.

To give a particularly pernicious example, consider the case of Arthur Golden’s exploitation and gross misrepresentation of Mineko Iwasaki. One of several geisha interviewed by Golden in the course of research conducted for his bestselling novel, Memoirs of a Geisha, Golden not only breached Iwasaki’s confidentiality by naming her as a source, but based a significant portion of his book on her life without permission, misrepresented actual historical details for sensationalist purposes, and generally twisted Iwasaki’s narrative. She sued him for breech of contract in 2001, with Golden settling out of court two years later. While Iwasaki was subsequently moved to write her own bestselling autobiography – Geisha, A Life – to try and ameliorate the damage, his appropriative actions nonetheless caused her material harm. And meanwhile, the film adaptation of Golden’s novel, which celebrated the worst of his changes, was critically acclaimed in the West, further contributing to the exoticisation of Asian women in general and geisha culture in particular. But why should that matter? It’s just a story.

Isn’t it?

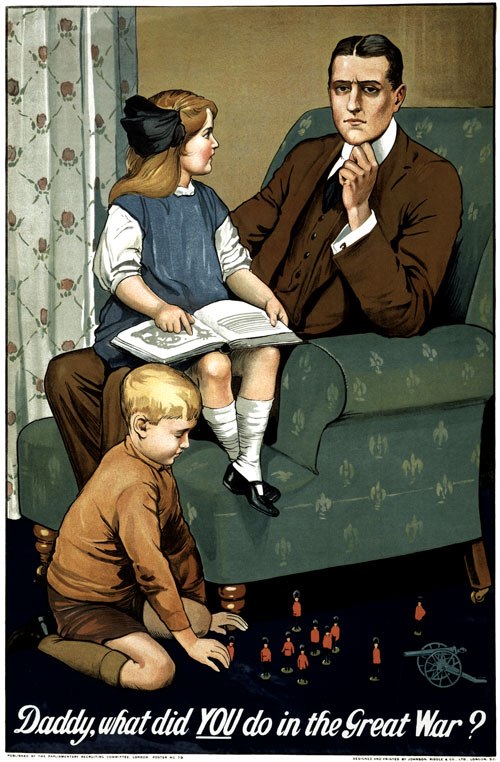

In my bookmarks bar is a folder called Narrative Influencing Reality, where I keep track of articles, posts and news items that show a correlation between fictional stories and the real world. The first link is the famous story about how, in the late 1940s, the writers of the Superman radio serial managed to stymie the resurgence of Klu Klux Klan memberships by having Superman fight the Klan. They knew that the story mattered; that people in the real world looked up to Superman, even though he was fictional, and could thus be persuaded to use him as a moral compass. This is a positive example of narrative influencing reality. But there’s also plenty of negative examples, too, such as evidence that the over-the-top “romantic” gestures popularised in romantic comedies can promote social acceptance of stalking, or the real-world racist backlash against Asians provoked by the film Red Dawn.

As writers, we know that stories matter, or we wouldn’t bother to tell them. Narrative is a force that shapes our humanity, our history, and our perception of others – and that is why unresearched, stereotypical and thoughtless portrayals of vulnerable groups can be so very harmful. Writing respectfully about others shouldn’t be such a terrible burden as to be worth angrily hijacking a festival keynote speech; it should just be basic good manners. As actress Jenn Richards recently said, “Artistic freedom is important, but it shouldn’t be at the expense of actual human lives.” And stories are always, in the end, about actual people: what they think, why they matter, and how we relate to them.

To say that stories have power, but to deny their consequences, is a particularly self-deluded form of irresponsibility. And Lionel Shriver, in denying the very real harm done by cultural appropriation, is guilty of it.