Recent news about Iran has been dominated by U.S. attempts to increase sanctions, and one could be forgiven for thinking the world hegemonic capitalist power is preparing war against a major nuclear power. The reality is far different: all the fuss is about a country where nine months of mass protests have not only weakened the state but also divided the ruling circles, making reconciliation at the top impossible. We are talking of a country where neoliberal policies and sanctions have created a serious economic crisis, with inflation projections of 50 percent this spring and youth unemployment estimated at 70 percent. So why are the U.S. and world media obsessed with the “threat posed by Iran”? — a threat that must be curtailed with “severe” sanctions or war? And what is the future for the protest movement in the midst of all this?

Recent news about Iran has been dominated by U.S. attempts to increase sanctions, and one could be forgiven for thinking the world hegemonic capitalist power is preparing war against a major nuclear power. The reality is far different: all the fuss is about a country where nine months of mass protests have not only weakened the state but also divided the ruling circles, making reconciliation at the top impossible. We are talking of a country where neoliberal policies and sanctions have created a serious economic crisis, with inflation projections of 50 percent this spring and youth unemployment estimated at 70 percent. So why are the U.S. and world media obsessed with the “threat posed by Iran”? — a threat that must be curtailed with “severe” sanctions or war? And what is the future for the protest movement in the midst of all this?

Current threats against Iran have little to do with nuclear issues. Iran is still two to five years away from achieving nuclear weapons capability. The drive for new sanctions cannot be understood unless one looks at the history of U.S. relations with Iran’s Islamic regime. The 1979 revolution deprived Washington of one of its most important allies in the Middle East, and the world superpower cannot be seen to be losing control in such a strategic area. Iran’s territorial waters include the Straits of Hormuz through which 40 percent of the world’s seaborne oil shipments flow. Also, at a time of world economic crisis the United States and its allies need a place to assert their authority. Yet since the launch of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq they have inadvertently increased Iran’s regional influence and strength.

The continuation of the conflict has another major cause. Iran’s Islamic regime has relied on crises and foreign enemies to survive. Otherwise how could it explain its failure to achieve any of the basic demands of 1979 after 31 years in power? The “external” enemy is also essential for justifying continued repression.

Iranian workers and political activists (with the possible exception of supporters of the former Shah) are unanimous: new “crippling” sanctions, bombing Iranian nuclear sites, or a military attack would be a disaster. Sanctions will let the regime off the hook, as the regime will blame severe economic conditions entirely on the embargo.

In April of this year Washington unveiled its new nuclear policy, which limits its use of nuclear weapons but excludes from its pledge “outliers” such as Iran and North Korea. Protests and demonstrations inside Iran should be seen within this context. The protests continue due to the tenacity and courage of thousands of Iranians, though more sporadically in the face of severe repression. But everyone, from government to “reformists” to revolutionary opposition, now agrees that the protests are no longer about who should be “president,” but about the very existence of the religious state.

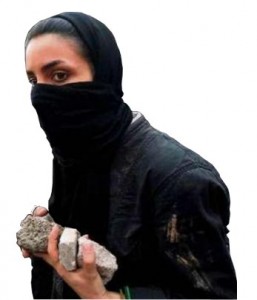

Reports from some recent protests suggest that for the first time in the last 30 years many women demonstrators didn’t wear head-scarves or hijabs. On December 27, 2009, security forces at a number of locations had to retreat, as demonstrators burned police vehicles and basij posts and erected barricades. Videos show instances where police and basij were captured and detained by demonstrators and three police stations in Tehran were briefly occupied. Demonstrators also set fire to Tehran’s Bank Saderat.

Since early 2010 basij and Revolutionary Guards have been unleashed to further impose an atmosphere of terror. Hundreds have been incarcerated, arrested worker activists have been fired, and leftists have been rounded up and in some cases issued death sentences.

Conservative Divisions

Despite the bravado of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, the demonstrations of 2009-10 have divided the conservatives. While supporters of Ahmadinejad openly call for more arrests and even execution of political opponents, the parliamentary “principalists” preach caution.

In January 2010, a parliamentary committee publicly blamed Tehran’s former prosecutor, Saeed Mortazavi, a close ally of Ahmadinejad’s, for the death of three prisoners arrested in June. The committee found that Mortazavi had confined 147 opposition supporters and 30 criminals to a cell measuring only 70 square meters. The inmates were frequently beaten and spent days without food or water.

Ali Motahhari, a prominent fundamentalist parliamentarian, told the magazine Iran Dokht: “Under the current circumstances, moderates should be in charge of the country’s affairs.” He suggested holding Ahmadinejad accountable for the prison deaths and for fuelling the post-election turmoil. Iranian state television broadcasts debates between “radical” and “moderate” conservatives, in which some blame Ahmadinejad for the crisis. There are two reasons for this dramatic change in line:

- The winter demonstrations were a turning point, in that both conservatives and “reformists” came to realize how the anger and frustration of ordinary Iranians was taking revolutionary forms.

- The principalists are responding to a number of “proposals” by leading “reformists” — as a last attempt to save the Islamic Republic. Fearful of revolution, “reformists” — from June 2009 presidential candidate Mir-Hossein Moussavi to former president Mohammad Khatami — have made conciliatory statements, and the moderate conservatives have responded positively.

In a clear sign that “reformists” have heard the cry of revolution, Moussavi’s initial response to the winter 2009 demonstrations was to distance himself from them, emphasizing that neither he nor Mehdi Karroubi had called for them. His January 1 statement “Five stages to resolution” was a signal to both his supporters and opponents that this was truly the last chance to save the regime.

Western reportage of the statement concentrated on his comment “I am ready to sacrifice my life for reform.” Iranians are well known for their love of “martyrdom,” from Ashura to the Fedayeen Islam in 1946, to the Marxist Fedayeen (1970s-80s). Iranians have been mesmerized by the Shia concept of martyrdom, a yearning to put their lives at risk for what they see as a “revolutionary cause.” But Moussavi will no doubt go down in history as the first Iranian to put his life on the line for the cause of “reform” and compromise!

Moussavi’s plan was seen as a compromise because it did not challenge the legitimacy of the current president and “presents a way out of the current impasse,” demanding more freedom for the “reformist” politicians, activists and press, as well as accountability of government forces, while reaffirming allegiance to the constitution of the Islamic regime, as well as the existing “judicial and executive powers.”

Moussavi’s statement was followed on January 4 by a “10-point proposal” from the self-appointed “ideologues” in exile of Iran’s Islamic “reformist” movement: Akbar Ganji, Abdolkarim Soroush, Mohsen Kadivar, Abdolali Bazargan and Ataollah Mohajerani.[1] Fearful that Moussavi’s plan will be seen as too much of a compromise, the five call for the resignation of Ahmadinejad and fresh elections under the supervision of a new independent commission to replace that of the Guardian Council. Later Khatami and another former president, Ali Akbar Rafsanjani, publicly declared their support for the compromise, while condemning “radicals and rioters.” Khatami went further, insulting demonstrators who called for the overthrow of the Islamic regime.

All in all, winter was a busy time for Iran’s “reformists,” terrified by the radicalism of the demonstrators and desperate to save the clerical regime. Inevitably the reformist left, led by the Fedayeen Majority, is submissively following the Moussavi-Khatami line. However, inside Iran there are signs that the leadership of the Green movement is facing a serious crisis. None of the proposals address the most basic democratic demand of growing numbers of Iranian protestors: separation of state and religion.

On the Iranian left, arguments about the “principal contradiction” and “stages of revolution” seem to dominate current debates. While some Maoists argue for a “democratic stage” of the revolution, citing the relative weakness of the organized working class, the Coordinating Committee for the Setting Up of Workers’ Organizations (Comite Hahamhangi) points out that the dominant contradiction in Iran, a country where 70 percent of the population lives in urban areas, is between labor and capital. They say that the level and depth of workers’ struggles show radicalism and levels of organization and that the Iranian working class is the only force capable of delivering radical democracy.

Leftwing organizations and their supporters are also discussing the lessons of the recent demonstrations. Sections of the police and soldiers are refusing to shoot demonstrators and the issue of organizing radical conscripts in order to divide and reduce the power of the state’s repressive forces must be addressed. In some working class districts around major cities the organization of neighborhood shoras (councils) has started.

Official celebrations of the 1979 uprising that brought down the shah’s regime stood in total contrast to the events of 31 years ago. The state’s lengthy preparations for the anniversary of the revolution included the arrest of hundreds of political activists, hanging two prisoners (for “waging war on god”), and blocking internet and satellite communications. The government brought busloads of basij paramilitaries and people from the provinces to boost the number of its supporters — it considers the majority of the inhabitants of Tehran to be opponents.

The 48-hour internet and satellite blackout was so comprehensive that the regime succeeded in stopping its own international media communications. The basij blocked all routes to Azadi Square by 9 a.m. and dispersed large crowds of oppositionists who had gathered at Ghadessiyeh Square and other intersections, preventing them from reaching the official celebration. From the speakers’ podium, surrounded by basij and Revolutionary Guards, many dressed in military uniform, Ahmadinejad produced yet another fantastic claim. In the two days since his instruction to step up centrifuge-based uranium enrichment from 3 percent to 20 percent, this had already been achieved! Nuclear scientists are unanimous that such a feat is impossible. The crude display of military power, typical of the state-organized shows that dictators have always staged, together with the severe repression in the run-up to the anniversary, had nothing to do with the revolution it was supposed to commemorate.

In fact, the events of February 11, 2010 were the exact opposite of February 10-11, 1979, when the masses took to the streets and attacked the regime’s repressive forces, when prison doors were broken down by the crowds and political prisoners released, when army garrisons were ransacked and the crowds took weapons to their homes and workplaces, when the offices of the shah’s secret police were occupied by the Fedayeen, and when air force cadets turned their weapons against their superiors, paving the way for a popular uprising.

The show put on by our tin-pot dictators was an insult to the memory of that uprising. Yet despite all the efforts and mobilization preceding the official demonstration, despite the fact that confused and at times conciliatory messages of “reformist” leaders had disarmed sections of the Green movement, the regime could muster only 50,000 supporters. Meanwhile tens of thousands in Tehran and other cities took part in opposition protests — even in the streets close to Azadi Square, despite the presence of large numbers of basij. The protests were so loud that, according to Tehran residents, the state broadcast of Ahmadinejad’s speech had to be halted and instead TV stations showed the flags and crowds to the accompaniment of stirring music. Fearing that the basij might not be able to control the protesters gathering in neighboring squares, the government decided to start its extravagant ceremony early and then cut it short.

Attempts at compromise by Green movement leaders in open and secret negotiations with the office of the “supreme leader” failed.[2] By early February, it was clear that no deal was in the cards. As always, the main problem with our “reformists” is that by remaining loyal to the “supreme leader,”[3] by condemning the popular slogan, “Down with the Islamic regime,” they fail to understand the mood of those who have taken to the streets. The movement is adamant in its call for an end to the current religious state — the repeated shouts of “Death to the dictator” are directed at the so-called “supreme leader” himself.

The February protests marked a setback for Moussavi and Karroubi — not just in their politics, but also in their tactics. First, it is foolhardy to organize demonstrations to coincide with the official calendar of events, as it allows the regime to plan repression well in advance. Second, it was absurd to call on people to join the regime’s demonstrations and, third, opposition to a dictatorship cannot simply rely on demonstrations. The state has unleashed its most brutal forces against street protesters, and we need to consider strikes and other acts of civil disobedience.

A lot has been written by Persian bloggers about the “lack of charisma” of Moussavi and Karroubi. However, the truth is their main problem is not personality, but dithering. This has cost them dearly at a time when opposition to the regime in its entirety is growing. The Islamic version of capitalism has brought about much harsher conditions for the working class and the poor. The state’s own statistics show a constant growth in the gap between rich and poor. The impoverishment of the middle classes, the abject poverty of the working class, the destitution and hunger of the shantytown-dwellers — these are reasons why the urban protests continue.

On February 15 Hillary Clinton cited the economic and political power of the Revolutionary Guards as a sign that “Iran is moving towards a military dictatorship.” Yet there is nothing new in the power of the Revolutionary Guards. Since 1979 they have been the single most important pillar of the state, involved in every aspect of political and military power. What is new is their involvement in capitalist ventures, empowered by the relentless privatization plans driven by the IMF and World Bank.

In recent years Revolutionary Guards have accumulated vast fortunes through the acquisition of privatized capital — precisely the pattern seen in the former Soviet Union and elsewhere. Those in power, often with direct connections to military and security forces, are able to purchase the newly privatized industries. That is the case with many U.S. allies, yet we have not heard the State Department criticize “creeping military dictatorships” in those countries.

No doubt, as repression increases, Iranians’ hatred of the basij and Revolutionary Guards will increase. However, they don’t need the crocodile tears of the U.S. administration — indeed interventions like those of Clinton and condemnations of the repression coming from the U.S. and European governments tend to damage the movement. Iranians are well aware of the kind of “democratic havens” created by the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the last thing they want is regime change U.S.-style.

Working Class Response

As repression increases and mass demonstrations are replaced with localized protests, many point out the significance of workers’ strikes in the overthrow of the Shah’s regime and attention is turning towards the unprecedented levels of worker protests. In the words of one labor activist, “a Tsunami of workers’ strikes.”[4] Even before the new sanctions, the economic situation has worsened. Hundreds of car workers — the elite of Iran’s working class — are being sacked every week.

The involvement of the working class in the political arena has increased qualitatively. Four workers’ organizations — the Syndicate of Vahed Bus Workers, the Haft Tapeh sugar cane grouping, the Electricity and Metal Workers Council in Kermanshah, and the Independent Free Union — published a joint statement declaring support for the protests and specifying what they call the minimum demands of the working class. These include an end to executions, release of imprisoned activists, freedom of the press and media, the right to set up workers’ organizations, job security, abolition of all misogynist legislation, declaration of May 1 as a public holiday, and expulsion from workplaces of government-run organizations. Meanwhile, Tehran’s bus workers have issued a call for civil disobedience to protest against the holding of Mansour Osanloo in prison.

Workers involved in setting up nationwide councils have issued a radical political statement regarding what they see as the priority demands that Iranian workers ought to raise. Emphasizing the need to address the long-term political interests of the working class, they also call for unity based around immediate economic and political demands.

There are reports of strikes and demonstrations in one of Iran’s largest industrial complexes, Isfahan’s steel plant, where privatization and contract employment have led to action by the workers. Leftwing oil workers/employees are reporting disillusionment with Moussavi and the “reformist” camp amongst fellow workers and believe there is an opportunity to radicalize protests in this industry, which is critical to the regime’s survival.

In March 2010, many prominent labor activists, including Osanloo, who are currently in prison, were sacked from their jobs for “failing to turn up at work,” prompting protests in bus depots and the Haft Tapeh sugar cane plant. In December 2009 Lastic Alborz factory workers struck for unpaid wages. There have been protests at dozens of other workplaces.

Future of the Protests

Even if the two main factions of the regime had achieved a compromise, it was unlikely that such a move could have defused the movement. However Moussavi, Karroubi and Khatami have failed to gain anything from their attempts at “reconciliation”; they are well aware that any additional talk of compromise will further reduce their influence amongst protesters. That explains recent statements by Moussavi, who in early April told a group of reformists in Parliament that the Iranian establishment continued to lose legitimacy: “One of the problems is that the government thinks that it has ended the dissent by ending the street protests.”[5]

Moussavi said that people have lost confidence in the state because of widespread corruption, incompetence and mismanagement since the presidential election. He said the movement needed to expand its influence among social groups like teachers and workers. “Our interests are intertwined with their interests, and we need to defend their rights,” he said. Khatami echoed this message: “If the authorities do not come up with effective policies the coming year will be the year of social crises.”[6]

Iran is bracing itself for another turbulent year, and most observers believe the working class and youth will play a greater role in the coming protests.

By Yassamine Mather: from New Politics

Recent news about Iran

Recent news about Iran