Yassamine Mather reports on the February 11 Revolution Day celebrations

Last week’s official celebrations of the February 1979 uprising that brought down the shah’s regime in Iran stood in total contrast to the events of 31 years ago.

The Islamic state’s lengthy preparations for the anniversary of the revolution included the arrest of hundreds of political activists, hanging two political prisoners (for “waging war on god”), and blocking internet and satellite communications. In addition, the government brought busloads of bassij paramilitaries and people from the provinces to boost the number of its supporters – it considers the majority of the 14 million inhabitants of Tehran to be opponents.

The 48-hour internet and satellite blackout was so comprehensive that the regime succeeded in stopping its own international press and media communications. On the morning of February 11 connections to Iran’s state news agency and Press TV were lost. Foreign press and media reporters found themselves confined to a platform next to where president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was speaking. Neighbouring streets and squares were barred to them. The bassij blocked all routes to Azadi Square by 9am and dispersed large crowds of oppositionists who had gathered at Ghadessiyeh Square and other intersections, preventing them reaching the official celebration.

From the speakers’ podium, surrounded by bassij and revolutionary guards, many of them dressed in military uniform, Ahmadinejad produced yet another fantastic claim. In the two days since his instruction to Iran’s nuclear industry to step up centrifuge-based uranium enrichment from 3% to 20%, this had already been achieved! Nuclear scientists are unanimous that such a feat is impossible.

Huge flags surrounded the Azadi Square podium and the official demonstration was dominated by military figures – typical of the kind of state-organised shows dictators such as the shah have always staged. The crude display of military power, together with the severe repression in the run-up to the anniversary, had nothing to do with the revolution it was supposed to commemorate.

In fact the events of February 11 2010 were the exact opposite of February 10-11 1979, when the masses took to the streets and attacked the repressive forces of the regime, when prison doors were broken down by the crowds and political prisoners released, when army garrisons were ransacked and the crowds took weapons to their homes and workplaces, when the central offices of Savak (the shah’s secret police) were occupied by the Fedayeen, and when airforce cadets turned their weapons against their superiors, paving the way for a popular uprising by siding with the revolution.

The show put on by our tinpot religious dictators was an insult to the memory of that uprising. Yet despite all the efforts and the mobilisation that had preceded the official demonstration, despite the fact that the confused and at times conciliatory messages of ‘reformist’ leaders had disarmed sections of the green movement, the regime could only muster 50,000 supporters. Meanwhile tens of thousands in Tehran and other cities took part in opposition protests – even in the streets close to Azadi Square despite the presence of large numbers of bassij. The protests were so loud that, according to Tehran residents, the state broadcast of Ahmadinejad’s speech had to be halted and instead TV stations showed the flags and crowds to the accompaniment of stirring music. Fearing that the bassij might not be able to control the protesters gathering in neighbouring squares, the government decided to start its extravagant ceremony early and then cut it short. So, despite only beginning at 10am, it had finished by 11.30.

Over the last few months there has been a lot of official nostalgia about the1979 revolution and ironically there are undoubtedly political parallels with the current situation – not least the fact that, just like Ahmadinejad and ‘supreme leader’ Ali Khamenei today, in February 79 ayatollah Khomeini was not on the side of the revolution. In the words of Mehdi Bazargan (Khomeini’s first prime minister), “they wanted rain and they got floods” (in other words, they wanted a smooth transfer of power, with the repressive, bureaucratic and executive organs of the royalist state left intact).

Yet the events of February 10-11 1979 shattered those hopes. No wonder the first official call by Khomeini, on the day the Islamic republic came into existence, was for people to hand over seized weapons to the army and police, for ‘order’ and for an end to strikes and demonstrations. From the very beginning religious clerics in Iran were an obstacle to revolution and for the last 31 years all factions of the Islamic Republic, including the ‘reformists’, have done their utmost to negate what was achieved with the bringing down of the shah’s regime.

Looking back at the events of 1979, in many ways it is amazing to think that a rather weak, confused and divided left managed to accomplish so much in such a short time. But for many Iranians of a different generation the current struggles are indeed the continuation of the same process – and many of them are determined to continue this struggle, however long it takes.

‘National unity’

Of course, if the anniversary of the revolution was not a good day for the government, the ‘reformist’ leaders of the green movement too had little to celebrate. Fearful of growing radicalisation, as witnessed by the Ashura protests in December, they spent most of January in both open and secret negotiations with the office of the supreme leader searching for a compromise.[1] Even though by early February it was clear that no deal was on the cards, they continued to issue confusing statements about how to approach the official celebrations.

Both Mehdi Karroubi and Mir-Hossein Moussavi implied that participation in the demonstration (official or otherwise) was important as a show of ‘national unity’. They condemned any attack on the bassij and other militia and repeated their declarations of allegiance to the Islamic Republic. Many of their supporters joined the official protests wearing no identifying colours and were therefore counted by the regime as supporters.

As always, the main problem with our ‘reformists’ is that by remaining loyal to the ‘supreme leader’,[2] by condemning the popular slogan, ‘Down with the Islamic regime’, they fail to understand the mood of those who have taken to the streets in protest. If for a while they were lagging behind the protests, today they no longer even understand the movement they claim to lead. That movement is adamant in its call for an end to the current religious state, an end to the rule of the vali faghih (Khamenei, whose ‘guardianship of the nation’ is supposed to represent god on earth) – the repeated shouts of ‘Death to the dictator’ are directed at the so-called ‘supreme leader’ himself.

The February 11 protests marked a setback for Moussavi and Karroubi – not just in terms of their politics, but also in their choice of tactics. First of all, it is foolhardy to organise demonstrations to coincide with the official calendar of events, as it allows the regime to plan repression well in advance. Secondly, it was absurd to call on people to join the regime’s demonstrations and, thirdly, opposition to a repressive dictatorship cannot simply rely on demonstrations. The state has unleashed its most brutal forces against street protesters, and we need to consider strikes and other acts of civil disobedience too.

A lot has been written by Persian bloggers about the ‘lack of charisma’ of Moussavi and Karroubi. However, the truth is their main problem is not personality, but dithering. This has cost them dear at a time when opposition to the regime in its entirety is growing, and the left can only benefit from this.

The anniversary of the revolution reminded Iranians of the slogans of the February 1979 uprising. The principal demands of the revolution were for freedom, independence and social justice (the ‘Islamic republic’ was a post-revolutionary constitutional formula imposed by the clergy). Thirty-one years later, no-one, not even the majority of Khomeini’s own supporters, who currently form the green leadership, claim there is any democracy in the militia-based monster of a state they helped to create.

Iran’s independence from foreign powers is also debatable. US hegemony might be in global decline, but in Iran, following America’s defeat in February 1979 and the subsequent US humiliation of the embassy hostage-taking in 1980, the last two and a half decades have seen a revival of US influence. As discussed in detail at the February 13 Hands Off the People of Iran day school in Manchester (see opposite), we can even see US influence during the Iran-Iraq war (Irangate and the purchase of US arms via Israel). In the late 1980s US policies of neoliberalism and the market economy dominated Iran’s financial and political scene and since 2001 the Iranian state has supported US military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan.

On the issue of social justice, even though the previous regime’s downfall had a lot to do with class inequality, the Islamic version of capitalism has brought about much harsher conditions for the working class and the poor. The Islamic state’s own statistics show a constant growth in the gap between rich and poor. The impoverishment of the middle classes, the abject poverty of the working class, the destitution and hunger of the shantytown-dwellers – these are all reasons why the current protests continue in urban areas.

Crocodile tears

In the midst of all this internal conflict, Iranians face the continued threat of war and sanctions. On February 15 Hillary Clinton declared: “Iran is moving towards a military dictatorship.” Yet there is nothing new in the power and role of the revolutionary guards in Iran. Ever since 1979 they have been the single most important pillar of the religious state, involved in every aspect of political and military power. What is new is their involvement in capitalist ventures, empowered by the relentless privatisation plans driven by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

In recent years capitalists in Iran and elsewhere have complained about the revolutionary guards’ accumulation of vast fortunes through the acquisition of privatised capital – precisely the pattern seen in eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union and elsewhere. Those in power, often with direct connections to military and security forces, are in a position to purchase the newly privatised industries. That is the case with many US allies in the region, yet we have not heard the state department commenting about ‘creeping military dictatorships’ in those countries.

No doubt, as repression increases, Iranians’ hatred of the bassij and revolutionary guards will increase and they will respond to these forces as they did in the protests of late December and last week. However, they do not need the crocodile tears of the US administration – indeed interventions like those of Clinton and condemnations of the repression coming from the US and European countries tend to damage the protest movement inside Iran. After all, Iranians are well aware of the kind of ‘democratic havens’ created under US military occupation in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the last thing they want for their own country is regime change US-style.

It is difficult to predict how the opposition movement will develop, but those of us who have argued that the current protests have economic as well as political causes are in no doubt that we will witness many more street demonstrations, strikes and other forms of civil disobedience. The state is clearly gearing up for another round of repression and there is no sign that those arrested in the last few weeks will be released. Death sentences have been passed on a number of political prisoners, some of them arrested prior to the elections of June 2009 (some have been found guilty of the crime of participating in protests held while they were in prison!).

Even before the new wave of sanctions hits the country, the economic situation has worsened. Thousands of workers are about to lose their job following the bankruptcy declaration of the electricity and power authority last week. Hundreds of car workers – the elite of the Iranian working class – are being sacked every week. On the other hand, the involvement of the working class in the political arena has increased to such an extent that even the BBC Persian service admits we are witnessing a “qualitative change” in workers’ protests.[3]

Four workers’ organisations – the Syndicate of Vahed Bus Workers, the Haft Tapeh sugar cane grouping, the Electricity and Metal Workers Council in Kermanshah, and the Independent Free Union – have published a joint statement declaring their support for the mass protests and specifying what they call the minimum demands of the working class.[4] These include an end to executions, freedom of the press and media, the right to set up workers’ organisations, job security, an end to temporary ‘white contracts’, equality in terms of pay and conditions for women workers, abolition of all misogynist legislation, the declaration of May 1 as a public holiday with the right of workers to demonstrate and gather freely on that day, the expulsion of religious workers’ organisations, which act as spies, from workplaces …

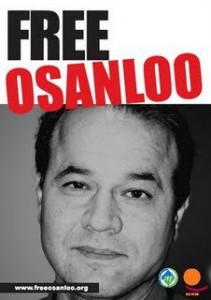

Meanwhile, Tehran’s bus workers have issued a call for civil disobedience: “Starting March 6, we the workers of the Vahed company, will wage acts of civil disobedience … to protest the against the holding of Mansoor Osanloo in prison. We appeal to the Iranian people and to the democratic green movement to join us by creating a deliberate traffic jam in all directions leading to Valiasr Square.”[5]

Workers involved in setting up nationwide councils have issued a radical political statement regarding what they see as priority demands Iranian workers ought to raise at this stage. Emphasising the need to address the long-term political interests of the working class, they also call for unity based around immediate economic and political demands.

As the struggles in Iran enter a new stage, where the weakness of the ‘reformist’ leaders is causing despair amongst sections of the youth, and at a time when the US, Israel and now Saudi Arabia are issuing threats of direct military action and sanctions, the need for international solidarity is stronger than ever before.

Notes

- See ‘Reformists fear revolution’ Weekly Worker January 14.

- See, for example, ‘Karroubi accepts Ahmadinejad as Iran’s president’ The Daily Star (Lebanon), January 26.

- www.bbc.co.uk/persian/iran/2010/02/100204_l12_ar_labour_movement.shtml

- See www.iran-chabar.de/news.jsp?essayId=27347

- ahwaznewsjidid.blogfa.com/post-3521.aspx