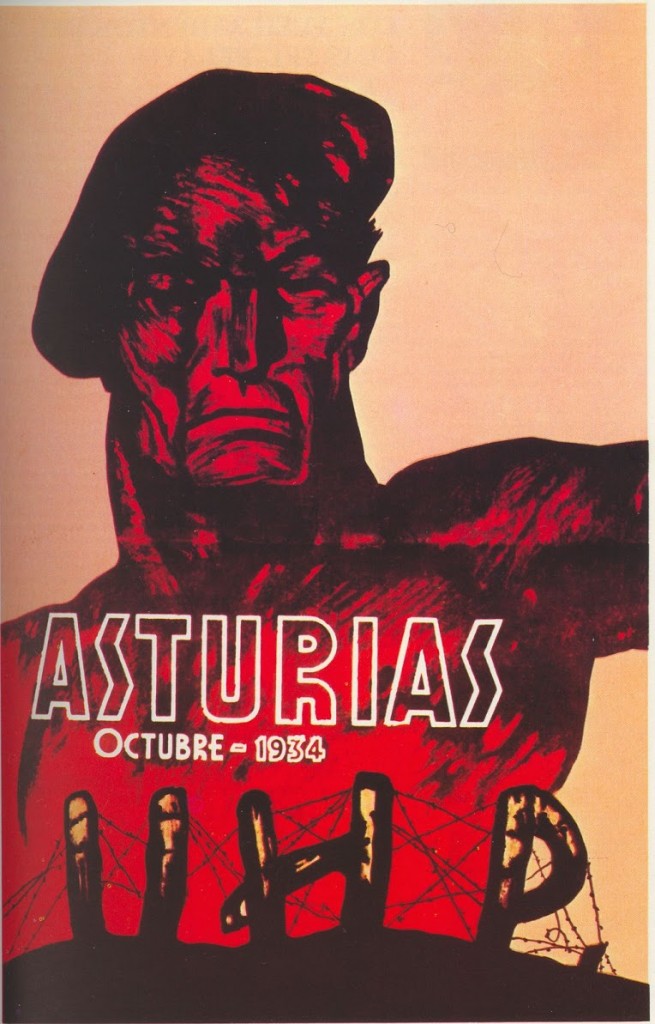

Calm and courageous from the outset, the handsome gladiator who is to scatter the seeds of a new society of active producers who shall live without masters and without tyrants, in perfect harmony with other producers and other villages where other guerrillas gladiators as handsome and courageous as himself, will have established Libertarian Communism as a superior arrangement for a life of justice and dignity

Calm and courageous from the outset, the handsome gladiator who is to scatter the seeds of a new society of active producers who shall live without masters and without tyrants, in perfect harmony with other producers and other villages where other guerrillas gladiators as handsome and courageous as himself, will have established Libertarian Communism as a superior arrangement for a life of justice and dignity

Published by the Grupo Cultural de Estudios Sociales de Melbourne/Acracia Publications, October 2013

By Way of a Preamble

“One of the best known CNT and FAI militants in La Felguera (Asturias), the leading steel town in the province, sent us the following account of what he witnessed during the October 1934 Asturian uprising. We think that these brief jottings will help shed light on matters that deserve to be known.”

Introduction by the original publishers of Cultura Proletaria (New York), republished as a CNT document in late 1973 by the Fomento de Cultura Libertaria (Paris). From exile, October 2013

******

La Felguera in the 1934 Asturian Revolution

LA FELGUERA was a CNT city with 4,000 workers organised into four unions – Steelworkers’, Construction Workers’, Mineworkers’ and General Trades. Those four unions together made up the Local CNT Federation. Even though the Alianza Obrera (Worker Alliance) thesis had not been acceptable locally, mentally the workers, driven by an ideal of redemption, were disposed to take part in any forceful undertaking likely to sweep obstacles or barriers out of the path of humanity.

The Socialists held a number of talks with our Federation to gauge where we would stand in the event of an insurrection launched by them. The response from our Federation was throughout that in any undertaking related to the well-being of workers and breaking the bonds of slavery, not only would it join a general strike but it would support the insurgents, and its men would be in the van on every battlefront, weapons in hand and flying their own libertarian ideas. A caution was issued to the effect that no Marxist dictatorship would be tolerated and that the Federation would invest all its efforts into upholding the idea of freedom in its thoughts and deeds.

Those discussions took place in August 1934, prior to the CNT Plenum held in Gijón, at which the matter of the Alianza Obrera was scheduled for debate. La Felguera spoke out against amalgamating with the socialists and other political factions and, given this uncompromising stance, relations were subsequently on the cool side. Nevertheless, La Felguera kept closely in touch with the Gijón unions, especially with José María Martínez* and Avelino G Entrialgo who, unless we are mistaken, served on the committee of the Alianza Obrera.

Since our Federation, and other unions, opposed the Alianza, it was bereft of news, generating something of a gulf between those militants who supported and the others who opposed the Alianza. Things remained like this until 5 October when the uprising began. Events then demonstrated the sterility of such an amalgamation of divergent forces.

On 5 October, two currents – the CNT on the one side and the socialists on the other – were brought together by the need to counter the might of the state and capitalism. In La Felguera, as in every town across Asturias, there were rumours to the effect that the socialists were about to make their move. The La Felguera Local Federation knew nothing, absolutely nothing, it was said. What was it to do? There was great unease. Despite the intense cold, hundreds of workers roamed through the F. Duro park asking activists how much truth there was in the rumours of an imminent uprising, what positions they should take up and where were the guns. But the activists had no solid answers to give them. They assumed that, if the rising materialised, the Regional Committee would brief all its affiliated organisations. One comrade suggested that a commission de despatched to Sama (a socialist-dominated market town adjacent to La Felguera) on a fact-finding mission. Our Federation’s understanding was that it was up to the Asturian Regional Committee to keep them briefed; in the final analysis, those socialists who were to mount a rising took the view that CNT help might be of use, but the huddle of workers itching for a fight was so large and the demand for hard news so insistent that the Federation had to agree to a meeting with the socialists.

On 5 October, two currents – the CNT on the one side and the socialists on the other – were brought together by the need to counter the might of the state and capitalism. In La Felguera, as in every town across Asturias, there were rumours to the effect that the socialists were about to make their move. The La Felguera Local Federation knew nothing, absolutely nothing, it was said. What was it to do? There was great unease. Despite the intense cold, hundreds of workers roamed through the F. Duro park asking activists how much truth there was in the rumours of an imminent uprising, what positions they should take up and where were the guns. But the activists had no solid answers to give them. They assumed that, if the rising materialised, the Regional Committee would brief all its affiliated organisations. One comrade suggested that a commission de despatched to Sama (a socialist-dominated market town adjacent to La Felguera) on a fact-finding mission. Our Federation’s understanding was that it was up to the Asturian Regional Committee to keep them briefed; in the final analysis, those socialists who were to mount a rising took the view that CNT help might be of use, but the huddle of workers itching for a fight was so large and the demand for hard news so insistent that the Federation had to agree to a meeting with the socialists.

At 1.00 a.m., the delegation arrived at the Casa del Pueblo in Sama, which was packed with red-shirted workers. The response of socialists’ Executive Committee was that it knew nothing and was awaiting instructions from Madrid.

On hearing this, La Felguera’s workers concluded that in the end nothing would happen, and headed for home to get some sleep. But the Federation’s militants and officials kept a watching brief as armed gangs had been spotted on the outskirts of the town, as if waiting for word before going into action.

It was agreed that weapons should be made ready in case they were needed and as the grease was being removed from machine-guns and rifles two mighty dynamite blasts made the air ring. That was at 3.00 a.m. Five minutes after that we heard sustained rifle and machine-gun fire, signalling that the forces of capital and the forces of labour had locked horns. The fighting escalated and the rifle shots were drowned out by dynamite explosions as a veritable army of miners threw dynamite at the enemy’s strongholds in Sama.

It was agreed that weapons should be made ready in case they were needed and as the grease was being removed from machine-guns and rifles two mighty dynamite blasts made the air ring. That was at 3.00 a.m. Five minutes after that we heard sustained rifle and machine-gun fire, signalling that the forces of capital and the forces of labour had locked horns. The fighting escalated and the rifle shots were drowned out by dynamite explosions as a veritable army of miners threw dynamite at the enemy’s strongholds in Sama.

In the face of this spectacle, the La Felguera proletariat —itching to get in on the fight — set aside recent grievances and, although no one had asked for its help, took up arms and organised its own attack on the Civil Guard barracks with four hundred men at 6.00 a.m.. By 8.00 a.m., our forces numbered in the thousands. Later, the whole town, men and women alike, amounted to a unique insurrectionist torrent.

Our Attack on the Civil Guard Barracks

Once the town had thrown in its lot with the uprising, an attack was organised on the Civil Guard barracks in the Urquijo barrio. After three hours of heavy rifle and machine-gun fire, the attack was called off, only to be resumed later using more effective methods.

A team of our fighters set off meanwhile for the town hall, seizing any arms found there and torching the parish records, seizing the keys to the church from the priest plus any weapons he had; the revolutionaries assured him that he had nothing to fear and that there was no threat to his life. The church doors were flung open, the building doused with petrol and burnt to the ground.

That same morning we mourned the death of one working man, killed by a shot from the Civil Guards barricaded inside the barracks; his name we have not been able to establish.

Although the Civil Guard held out in the barracks, the area was otherwise virtually in the hands of the insurgents who set up a revolutionary committee to co-ordinate the fighting, seize official buildings and raise the red-and-black flag over them.

The Escuelas Cristanas were also seized and turned into a headquarters; they also overran the Dominican monastery.

One of the Revolutionary Committee’s first moves was to take over the Duro-Felguera Works, arresting managing director Antonio Lucio Villegas; he was shown every consideration and brought to the Casa de la República where the other engineers live; a watchful eye was kept on him and he was promised that no harm would come to him, as were the rest of the Company’s engineers who were locked up with their families. Care was taken to ensure that they wanted for nothing and that they were appropriately looked after.

This is what the bourgeois press reported about our conduct after our surrender:

“This attitude on the part of the people of La Felguera deserves to be highlighted, since other self-styled redeemers of humanity purporting to champion high-minded ideas – (we refer to the rabid socialists) – twice tried to get their hands on these gentlemen in order to take justice into their own hands, but were determinedly and resolutely opposed by the La Felguera steelworkers’ leaders who hold anarchist beliefs, the assailants being told that they would only do so over their dead bodies.

That selfless and humane gesture by the Revolutionary Committee has been praised by the town and will surely be praised also by the whole of Asturias once it becomes known.” (21 October).

Organising Labour and the Proclamation of Libertarian Communism

Another of the immediate tasks facing the Committee was the organisation of labour in the factories and workshops where the avoidance of interruption was vital and from among the fighters was chosen a squad to staff each of the following works: Altos Hornos, Hornos de Cok, Hornos de Acero and Cooperativa Eléctrica. With the exception of the cooperative, all of these works remained in operation over a fortnight under the management of the workers themselves. On the afternoon of Friday 6 October, the Revolutionary Committee issued a statement announcing that the social revolution in Spain had begun and encouraged the workers to throw themselves into the struggle for libertarian communism.

In an addendum residents of the Urquijo barrio were urged to evacuate their homes before 6.00 p.m. This was because the barrio was the location of the Civil Guard barracks which would come under attack at that point if it failed to surrender, as it was blocking access to the Gijón highway and the La Vega station.

Before launching the attack, the Revolutionary Committee sent a message to the troops urging them to surrender; the message was ignored. At 8.00 p.m., the assault was launched, initially on a single front while other teams attacked with dynamite from the other side. After six hours of ferocious fighting, the cessation of gunfire from within the barracks signalled to us that it was all over. The enormous reinforced concrete fortress was overrun on both flanks.

In the course of the bombardment of the barracks, 26 year old Florentino González perished when a powerful explosive device blew him to smithereens.

With the barracks destroyed and all obstacles now removed, the rebels set about disarming private persons not in sympathy with the revolution.

Once all the key centres in the town were in our hands, on 7 October the Revolutionary Committee issued a manifesto proclaiming that the Social Republic had carried the day in La Felguera. A people’s assembly was scheduled for 3.00 p.m. so that the workers themselves could have their say as to how the new society should be organised.

With the entire town people gathered in the park, a Revolutionary Committee member addressed the huge crowd from the bandstand. He opened with an expression of regret that they had had to use violence against the Civil Guard, violence that might have been averted had they only surrendered. Then he asked for people’s views of how to proceed. Another Committee member cautioned that the rising was not yet over, for explosions could be heard in other towns, suggesting that the fighting continued and he argued that we were duty bound to bolster the ranks of the fighters in those places where victory had yet to be achieved. He closed by offering suggestions about the fighting and about the rationing of foodstuffs.

With the meeting at an end, thousands of La Felguera workers then made for a number of neighbouring towns to take a hand in the fighting there.

The town came out in favour of libertarian communism and the Committee, sticking to its principles, declared the abolition of money, introducing vouchers affording the town access to supplies; these were issued by the Distribution Committee organised along district lines, the better to tackle its mission. People adapted quickly to this rationing arrangement, especially given the ease whereby one’s needs could be met right there in the barrio, where the outlets dispensed whatever resources they had. The bakeries continued baking bread.

The revolutionaries established a Provisions Committee and a squad took charge of procuring food to meet the town’s needs. The ‘La Justicia’ Centre became a general produce warehouse for all manner of items; local shops drew from there for onward distribution around town.

The Revolutionary Committee sent out a call to all doctors and practice nurses and anyone involved in the medical profession, thereby establishing a medical corps that set to work immediately. Members of this corps wore Red Cross armbands and had special vehicles displaying the Red Cross. A larger version of the same cross was erected on Hospitals, first aid posts and pharmacies.

Since the government forces in Oviedo and Gijón had not yet been overcome – (quite the opposite, they were escalating their efforts supported by the air force) – the La Felguera revolutionaries devised an effective weapon with potential immediate impact. They built a number of armoured tanks which were deployed in several attacks to good effect. They circulated on the most dangerous front lines displaying the CNT-AIT-FAI initials.

Following the attack upon and destruction of the Civil Guard barracks, the rebels commandeered their horses and set up a mountain scout unit in the service of the revolution. That unit was tasked with patrolling locations through which there was a danger of enemy incursion.

Elsewhere in the Area

That done, the La Felguera revolutionaries set off to Oviedo and Gijón in search of news, ready to furnish reinforcements where necessary. In Oviedo they saw with their own eyes that the situation was taking a turn for the worse due to lack of guidance among the fighters inasmuch as none of the bigwigs had put in an appearance to offer any solutions or encourage the scattered groups to channel their activities as appropriate. Only one of the fronts, the one where Ramón González Peña was in charge, held firm and was making creeping progress. It was arranged that several people from La Felguera would travel to Oviedo with the intention of bringing influence to bear on the revolutionary ranks and introduce a change of tactics.

Four lorry-loads of thirty militants in each lorry set off from La Felguera; in each lorry, one of the most able comrades was chosen to direct the attacks. One of those comrades oversaw the fighting in the streets of Oviedo with some six hundred men while others went off to swell the ranks of those attacking the La Vega arms plant and other fronts.

That expedition included an armoured lorry driven by another comrade who, before going into action, toured all the fighting fronts under a hail of bullets by way of reconnaissance to find out where his help was most needed. During this reconnaissance trip, on reaching the Carabineer command post, he came upon a group of workers hurriedly deserting their positions and ceding them to the enemy. The carabineers seized upon this rout to recapture some positions, inflicting some losses on the red shirts. Realising the disorientation and danger, the comrades on the armoured lorry realised that that was where they were needed. The lorry advanced in the direction of the enemy and, without having to fire a single shot, forced the carabineer troops into retreating and taking refuge inside their barracks.

That operation complete, the comrade overseeing operations unloaded a machine-gun and set it up in the window of a nearby house with a commanding view of the command post. Two comrades remained behind to feed the machine-gun and the supervising comrade urged the retreating workers to return to their posts. The armoured lorry soon inspired their confidence and, once they had returned to their strategic posts, our comrade delivered an oration from a mere five metres from the barrack gates, urging the carabineers to surrender since further resistance was pointless. By way of a response, a volley of shoots from inside the barracks. Our machine-gun cranked up with some well-directed fire and the enemy fell silent; the harangue continued as he again urged them to lay down their weapons in the next five minutes and promised that their lives would be spared.

Those five minutes elapsed amid a sepulchral silence. After a moment or so another volley rang out from within the barracks. Whereupon the order was given for rifle and machine-gun to open up on the gates and windows and for bombs to be tossed on to the roof. Two minutes into the action the cornice of the building began to crumble and a white flag attached to the point of a sabre appeared at one of the windows. A cessation of gunfire was called for. At which point a lieutenant-colonel appeared, claiming responsibility for the resistance offered and promising to hand himself over as long as his life would be spared, or, if not his own, then the lives of his men. The comrade in charge of the lorry undertook to spare them all and on that promise they started to file out of the barracks. First out was the lieutenant colonel, followed by a major; then came others, officers or men. Within five minutes the barracks was entirely under the control of the revolutionaries who discovered some fine weaponry inside.

The CNT comrades arranged for the prisoners to be held in an adjacent house and for all their needs to be catered for; a guard was posted to ensure that they were not molested. Immediately after that a group showed up unexpectedly; they seemed to be red shirts, socialists or communists, in that both persuasions dressed in the same fashion and without reason or explanation they fired shots, killing two men. The comrade who had earlier delivered the harangue prior to the capture of the barracks condemned the shooting, stressing that it had been well out of order since the name of a noble and selfless ideal was not to be besmirched with the blood of the vanquished. The revolution’s aims were loftier than that and the needlessly expended shells were needed where resistance was still continuing. Our revolution had to target not men but institutions, and if we did not spare the lives of the vanquished, we were no better than capitalism’s hyenas.

After he had spelled these and other things out from the top of the lorry to a he mass of men and women a chorus of Long live the CNT and the FAI! sprang unanimously from every lip.

With that incident over, steps were taken to protect the remaining carabineers as detainees, the intention being to take them back to La Felguera and ask the people what should be done with them, our comrades being confident that no harm would come to them.

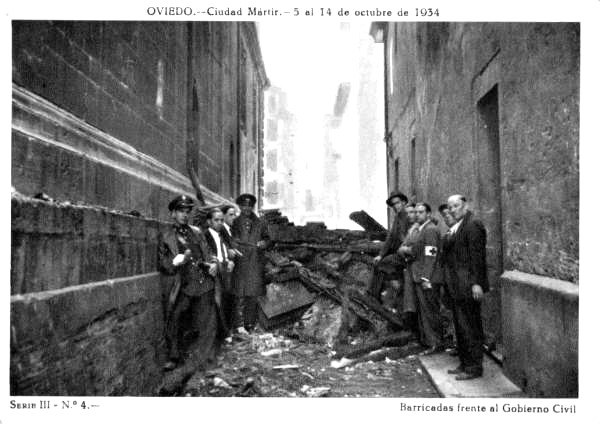

Trailing behind the armoured lorry a veritable army of revolutionaries of every hue headed for the civil government building. Before the attack began those in the retinue who were defenceless were called upon to go no further, for it could be taken for granted that machine-guns had been set up and carnage had to be avoided. Our comrades were keen to brave the danger alone, advancing in order to check that an attack could be mounted with some prospect of success. They did that but had progressed barely fifty metres along the street leading to the government building before a hail of bullets peppered their spy-shields. The attack lasted three quarters of an hour, it proving impossible for the lorry to break the intensely raking fire emanating from the line of police- and Assault Guard-manned machineguns.

Furthermore, that line remained unbroken because the sole machine-gun in the lorry had been knocked out of action and there was no way that rifle fire unaided could scatter the enemy. The decision was made to back off before returning with more effective fire-power. It had gone barely twenty metres before a burst from several machine-guns destroyed the vehicle’s four wheels. At which point a group of comrades, realising the danger we were in, orchestrated an attack from both flanks, distracting the troops, this distraction being seized upon in order to quit the lorry and salvage our weapons. This operation was pulled off just in time, for the government forces also then opened up from the cathedral.

We broke off momentarily from taking the government building in order to deploy more appropriate weaponry, a few comrades staying behind to give encouragement to the rebels whilst the La Felguera comrades headed for home to pick up another armoured lorry.

Before leaving Oviedo they went to check on the status of the carabineers captured following the surrender of the barracks. They had vanished from the scene, every one of them; days later we were informed that the Turón Committee made up of socialists and communists had ordered them shot, which order had been carried out in the town cemetery.

With a sour taste in their mouths, the comrades headed back to La Felguera in search of another lorry. There they met with a commission dispatched by Gijón, which spelled out the dire situation in which the fighters there were due to shortage of ammunition. That commission also revealed that the gunboat ‘Libertad’ had arrived and that its crew was preparing to come ashore.

The gunboat had already shelled the Cimadevilla barrio, demolishing several homes and killing a number of comrades. The delegation also brought news that Gijón had been entirely in the dark about the uprising right up until the moment it started, so no way had they been considered. Nor had anyone bothered to provide them with defensive equipment. They had weapons, but no ammunition. Having listened to the Gijón comrades’ case, it was decided that reinforcements would be despatched from La Felguera bringing munitions and bombs to bolster the insurgents’ ranks.

Two lorry loads of riflemen and an armoured lorry were put together and the expedition set off at 8.00 a.m. arriving in Gijón two hours later. The riflemen were forced to enter the city on foot because the gunboat ‘Libertad’ anchored in the port had the coal route lit up with searchlights. With its headlights turned off and braving the danger, the armoured lorry slipped through. It then headed for the El Llano barrio which was in the hands of Gijón’s revolutionaries where there discussed matters with the CNT comrades.

An attack plan was drawn up: it was to start at 10.00 a.m. The La Felguera and Gijón militants together toured the positions captured, rotating guards being posted on account of the fierce hail and snowstorm. At the slightest noise or unusual movement the sentries sounded the alert. Ay moving forwards, if he was a revolutionary, had to answer “FAI” when challenged, that being the password.

Having reviewed the positions the Committees took shelter from the torrential downpour, after posting the appropriate guards. At 4.00 a.m., after a short rest and just as they were preparing for the mission of the day ahead, the Revolutionary Committee received a message from the commander of the government forces in Gijón, making serious threats and ordering the revolutionaries in Cimadevilla, Verina and El Llano to surrender before sunrise and threatening to bomb the barrios mercilessly if that order was not complied with.

It was decided that the comrades should remain on the barricades in defensive mode, merely replying to enemy attacks, while the armoured lorry and another lorry load of riflemen set out to bolster the group that had set off uphill with José María Martínez, intending to cut off a column of 500 men landed from the gunboat ‘Libertad’ and who were closing on Oviedo along the Sotiello highway. An hour later, the reinforcements met up with the rebels led by José María Martínez, pressing on almost as far as Pinzales, where they were within reach of the government forces.

The revolutionaries, numbering about fifty, dug in in the high ground, preparing to launch an attack from there upon a column that outnumbered then by ten to one. A ferocious fire-fight erupted, but the troops, splitting up into lots of guerrilla teams, succeeded in encircling us after three hours of fighting, forcing us to retreat. The army sustained a number of losses and some revolutionaries were bayonetted during the withdrawal. One was a 17-year-old from La Felguera who kept his last remaining bullet for the Tercio sergeant who was about to take him prisoner. The sergeant was shot dead and our comrade was finished off with bayonets.

That same day, the air force began bombing the barrios held by the rebels, inflicting some casualties. But one of the planes was hit by a volley from the workers, perforating its fuel tank and forcing it to fly out to sea where it dumped its payload before making a forced landing on San Pedro beach.

After that and since further resistance was deemed futile for want of the right equipment, it was agreed to break off hostilities., some men making their way back to La Felguera hoping to cut off the column that was closing in on Oviedo by another route closer to the city.

Gijón fell to the forces of the state on 10 October. Revolutionary forces massed in Oviedo, the workers overrunning the La Vega arms plant where they found war materials galore, several thousand rifles and machine-guns. This weaponry was removed by lorry to the various towns around the province where it was assumed it was needed. Upwards of 2,000 rifles and 12 machine-guns were taken to La Felguera, as was a 10.5 calibre field-gun, one of the those captured by the revolutionaries in the storming of the Trubia arms plant.

All these weapons were deployed with precision. On 11 October a count had to be made of the cartridges, sentries sometimes being down to their last five or ten. Some were manufactured but not at the rate of 30,000 per day, which added up to just one bullet per combatant. Strict rationing had to be introduced so that the areas of stiffest resistance (such as the Pelayo barracks where the No 3 Regiment was dug in, the Santa Clara barracks defended by the Civil and Assault Guards and where word had it there were over two million rifle cartridges) did not go short.

Oviedo cathedral was also being stoutly defended by the Assault Guards who had taken it over.

Outrage

The La Felguera comrades, in conclave with some Gijón comrades scrutinising the dire situation before them, could see that Oviedo, the reactionaries’ target for the past six days, could not hold out any longer with the workers at such grave disadvantage. Fresh vigour needed to be injected into the fight and the (socialist) Provincial Committee’s belief that the enemy would hand himself over without a fight to the death had to be discounted. It needed to be made clear to that Committee that the despatches continuously arriving from several provinces were fooling nobody; they needed to be clear-sighted and operate on the basis of harsh facts. The Committee had to be made to see that if Oviedo did not fall that very day, they would be hard put to it to capture it over the ensuing days since the fighters would be worn out and pessimism starting to overwhelm everybody. At the same time, it was informed of the desire [of the CNT] to join the Provincial Revolutionary Committee.

After the matter was raised with the Provincial Committee, there were divergent interpretations of the circumstances, for we were assured that things were better than ever and that the attack could have been better organised. In short, that there were grounds on which to criticise the Committee’s work. But delegations were frequently arriving from the front lines to confirm our analysis and convinced, as we were, that the time for hesitation was over. At that meeting the Committee told us that the air force in León had fallen to the revolutionaries and would shortly be overflying the enemy positions. The commission of La Felguera and Gijón comrades stuck by their views and invited the Committee to tour the front lines and see the situation for itself. González Peña took up the challenge and made the inspection with a comrade of ours and was persuaded that they could not go on like that. As a result the CNT was welcomed on board to strengthen the Committee and boost morale on the battlefronts. Three comrades would join the Revolutionary Committee and another three would oversee the fighting where the resistance was at its stiffest. Among the latter were José María Martínez and two comrades from La Felguera who were to take up their posts that very night. The La Felguera comrades were due to head back to town to report on what had been agreed, while José María Martínez and another comrade from Gijón would remain in Oviedo, fighting the enemy forces. But before these comrades set off on their mission, the deafening roar of engines signalled the arrival of a huge deployment of aircraft. The crowd dashed out to verify if they were on the side of the revolution and raced through the streets and squares.

The planes overflew the barracks a few times dropping some packages. They then flew over the city dropping proclamations calling upon the revolutionaries to surrender, threatening to plunge the entire province into mourning if they did not comply.

Next, another plane screamed past, followed by a squadron of nine other planes and from a height of 200 metres began dropping bombs, causing countless fatalities and injuries. In the city square and across from the building housing the Revolutionary Committee, a bomb fell that caused 53 casualties (16 dead and the remainder wounded).

The people were outraged and fought back with a vengeance but the Revolutionary Committee, still consisting solely of socialists and communists, sensed that the situation was becoming unsustainable.

The La Felguera delegation set off at 5.00 p.m., being due back at 10.00 p.m. to join the Revolutionary Committee and reorganise the offensive. At 9.00 p.m., even as La Felguera was deciding which comrades would serve on the Provincial Committee, José María Martínez arrived with another comrade to report that, having gauged how things stood and the gravity of the situation, had given the rising up as a bad job and reported that it was entirely cut off by army troops. There was, consequently, no option but to pull out of Oviedo, to which end every vehicle available in the villages needed to head for the city.

When the matter was raised, some La Felguera personnel took issue with this and indeed felt distrustful, their view being that they had to carry on with the fight. The others, along with the Gijón comrades, argued that if the Provincial Committee was ordering a withdrawal, they had to withdraw, for the socialists and communists accounted for the bulk of the fighting personnel and for us to fight on alone would have been pointless.

Given the majority in favour of withdrawal, which had to be carried out on the night of 11 October, José María Martínez was charged by the Provincial Committee in Oviedo with bringing the withdrawal order around the villages and saving the necks of the village Committees and the Provincial Committee itself. José María, a well-intentioned fellow who could be trusted implicitly, set about carrying out that mission. But in Sama de Langreo, a mostly socialist town, there was already another Provincial Committee up and running; it consisted of socialists and communists and the rumour there was that José María Martínez was a turncoat. This was in those villages where the Marxists were in the ascendancy. The next day, he was found dead in Sotiello.

With the withdrawal under way, the comrades noticed that the fighting was fiercer than on previous days and they noticed that the whole thing had been a ploy, for which reason they made up their minds to head back to their respective home towns. Many of those from La Felguera did just that, returning to find that there was another Committee operating, one made up of anonymous comrades who had handed over to others who, being more committed to and heedful of the orders from the socialists, had begun the withdrawal. A manifest was issued explaining their dismay and detailing the ploy and pointing the finger at the Provincial Revolutionary Committee in Oviedo.

The comrades from the La Felguera Committee also reported that socialists had arrived from Sama to set up a committee there [in La Felguera] but that their plans had quickly been foiled.

Back to the fighting and the La Felguera comrades who remained in Oviedo until 18 October. The Distribution Committee was overhauled and they pressed on with the introduction of the new society. At that point, differences of opinion between socialists and anarchists escalated following the publication of some manifestoes urging the formation of a red army and the proclamation of a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Time and again, the La Felguera Committee held talks with the Provincial Committee, pointing out to it that its committees were helping create division in the rising, since not all of the fighters subscribed to the notion of a dictatorship, and urging it to call of that campaign before the CNT was obliged to call a halt to it by spelling out where it stood and what its aims were.

The Provincial Committee promised to issue a manifesto counselling against any divisive propaganda, since the times required that all strands within society join forces until the enemy had been seen off. Afterwards he people could choose whatever arrangement it thought best. Since this writer never saw the manifesto he is not in a position to say whether or not the agreement was honoured. What I witnessed later were manifestoes threatening serious grief for those who failed to abide by the Committee’s instructions and other outright displays of authoritarianism and dictatorial attitudes.

Towards Libertarian Communism

Widespread discontent was undermining the socialist grassroots in the villages, whereas the CNT was widening its theatre of operations and influence. La Felguera was the axis around which a fair number of villages turned once they gained detailed knowledge of how it was organised internally, its heroism and the daring of its fighters. Brand new advocates of CNT postulates began to appear in all the grassroots Marxist villages and some areas that appealed to La Felguera to send out personnel to form committees with an eye to introducing libertarian communism. One such village was Nava that sought our help in capturing the Civil Guard barracks, as indeed it did, a committee akin to the La Felguera committee being set up. It was the same story in Noreña and in Pola de Sierra, where the committees were made up of La Felguera comrades, and in Carbayin where there was a CNT branch and a couple of FAI groups. Infiesto too fell to the CNT without resistance, handing over all the rations necessary to the upkeep of the revolutionaries and keeping them in provisions. Infiesto was populated for the most part by comfortably-off petites bourgeois. Its population must have stood at around 2,000. Months before the rising, a lorry carrying socialists on an outing had been fired upon there; virtually the whole town was implicated in the attack and several people were wounded. When La Felguera hit town, it was not bothered in the least and the bank tellers made haste to hand over the keys of the banks to our comrades, which our comrades declined, making it known that it was not money they were after but justice and freedom.

Once they had seen how we acted they came over to our side and displayed a great willingness to assist us.

Nava has a population of some eight thousand but no CNT organisation and even the socialists are thin on the ground. In Pola de Sierra, the socialists were the pre-eminent influence; the population there stands at about 29,000. Noreña was Catholic and conservative in outlook.

To set out the differences between the performances of socialists and anarchists, and their respective sway within Asturian villages, one would have to reproduce the manifestoes issued by both factions and go into a detailed explanation of practical life in the areas where one or the other predominated.

Conclusion

When libertarian communism was proclaimed in La Felguera and money as a means of exchange done away with, the banks and savings funds and private companies were left untouched – except for the Duro-Felguera company which was raided on the night of the withdrawal (by whom we never knew), its safe cut open and some 150,000 pesetas lifted.

The Committee could not be held responsible for this. By contrast, where the socialists had the upper hand, the first thing they did was seize the banks and make off with the money deposited there.

Another thing that boosted the prestige of the CNT was how it conducted itself vis a vis defeated enemies; it saw to it that they wanted for nothing and the revolutionaries did them no harm and never, ever wrought vengeance on anybody. We could cite dozens of examples to prove this. We need only mention the case of the Duro-Felguera Company engineers and its managing director, on whom the Sama socialists tried to get their hands, in response to which the La Felguera comrades interposed themselves as reported in the quotation above from the bourgeois newspapers. And we have already spoken of the carabineers in Oviedo. We might also recall an Assault Guard caught on the hop by a patrol from La Felguera; when it made to arrest him, he attacked it. Overpowered and taken prisoner, he was brought before the Committee where, his mother having appealed on his behalf, he asked to be allowed to espouse our cause before dying. Since the people of La Felguera had no wish to turn gaoler, the Guard was dressed in civilian garb so that he might perform a few assignments. But a squad of revolutionaries from Sama, socialists, gave notice that they had more Assault Guards there as their prisoners and that he could be moved there to join the rest. The Guard plumped for that option and was moved there. [ENDS]

*****

ORDER OF THE LA FELGUERA REVOLUTIONARY COMMITTEE

(6 OCTOBER 1934)

To the People at large

The Social Revolution having triumphed in La Felguera, our duty is to organise distribution and consumption properly.

The Social Revolution having triumphed in La Felguera, our duty is to organise distribution and consumption properly.

Of the people, we ask a level head and prudence. There is a Distribution Committee to which anyone charged with meeting household needs should address himself; that Committee is based at the ‘La Justicia’ Workers’ Centre and anyone with a complaint or who needs to collect appropriate “authorisation” should look to that, as money has been abolished along with private ownership.

At three o’clock this afternoon, the town’s citizens should assemble in the park where appropriate guidance will be offered.

That is it for the moment; we remain, yours and for successful Revolution

The Revolutionary Committee

La Felguera, 6 October 1934

ORDER OF THE LA FELGUERA REVOLUTIONARY COMMITTEE

(17 OCTOBER 1934)

To date we have had no complaints from doctors, chemists, practice nurses and other professions who seemed far removed from our own concerns. By contrast, it seems that bakers and dealers in certain food items are out to place sand in the engine of revolution.

We are the enemies of pointless extremism, but they and any who might seek to imitate them, should be aware that we shall work swiftly and effectively. The people must be served as they deserve and with the dignity due to those who can lay unique claim to the title creator of all wealth.

La Felguera, 17 October 1934.

Source: La Revolución en Asturias 1934. Peque ños anales de quince d ías, Aurelio de Llano Roza de Ampudia, IDEA, Xixón, 1977

*****

* Death of José Maria Martinez, Gijón CNT leader in 1934

Fifty(!) years have passed since October 1934 and even now forces are still working to erase the truth about what happened back then. The talk today is of CNT leader José Maria Martinez, a man indisputably of the working class. While it is true that José M Martinez has left a record of loyalty within the workers’ movement, one that could only be equalled by another revolutionary as genuine as himself, it is hard to see one emerging. Besides, when it comes to remembering his death in October 1934 what really happened is a far cry from the agreed version. In some writings that appeared shortly before the civil war in Barcelona, as well as later in exile, the convention has been to say that an anarchist comrade from Asturias physically eliminated José Maria Martinez, something never confirmed.

Fifty(!) years have passed since October 1934 and even now forces are still working to erase the truth about what happened back then. The talk today is of CNT leader José Maria Martinez, a man indisputably of the working class. While it is true that José M Martinez has left a record of loyalty within the workers’ movement, one that could only be equalled by another revolutionary as genuine as himself, it is hard to see one emerging. Besides, when it comes to remembering his death in October 1934 what really happened is a far cry from the agreed version. In some writings that appeared shortly before the civil war in Barcelona, as well as later in exile, the convention has been to say that an anarchist comrade from Asturias physically eliminated José Maria Martinez, something never confirmed.

José Maria Martinez was found dead — sprawled across the railway cutting in Langreo in Sotiello, a town about eight kilometres Gijón — at three o’clock in the afternoon of 12 October 1934; he had been shot in the chest by a bullet from a Mauser rifle.

With the collapse of the revolutionary uprising in Gijón, José Maria Martinez moved to La Felguera along with other CNT comrades to continue the struggle in La Felguera and Oviedo. Although the battle was lost in Gijón, there was no let-up in the CNT revolutionary’s action. José Maria was a committed revolutionary and nothing or no one was going to prevent him from being in the forefront of the fighting. Intending to press the Central Revolutionary Committee to step up the struggle with an eye to capturing the regional capital, Oviedo, he and a few other comrades left La Felguera for Oviedo where his advice and suggestions were respectfully heeded, despite the false rumours that he had distanced himself from the socialists.

José Maria Martinez was a member the Revolutionary Committee in Oviedo, representing Gijón’s CNT members who had never doubted their comrade’s loyalty or integrity.

At a meeting of the Central Revolutionary Committee attended by Jose Maria Martinez on the night of 9-10 October 1934, it was decided to raise funds to support those comrades [in exile or clandestinity] who had most distinguished themselves during the fighting, especially the comrades from the War and Civic Committees, and a number of comrades —young miners — began robbing local banks. It isn’t known how much was raised, but what has been said is that the proceeds were also to be used to re-launch the newspaper Avance and support the CNT press.

The Revolutionary Committee assembled at 2.00 a.m. with José Maria Martinez and two other comrades from the CNT (who are still alive [1984]) who can corroborate my account. The communists, who were already attacking the Alianza Obrera, had by this time been given posts on the Central Revolutionary Committee and they too were at the meeting.

Believing the uprising to have been defeated, the Revolutionary Committee ceased to function as of 3.00 a.m. and, after taking receipt of a substantial sum of money, José Maria Martinez left Oviedo to return to La Felguera where he met with the local Committee to brief them on what had been agreed by the Central Revolutionary Committee in Oviedo. This did not go down well with the anarchist comrades in La Felguera. The argument reached such a pitch that one person denounced José Maria Martinez as a traitor. In view of the high tension and that some La Felguera comrades were refusing to listen, José Maria Martinez left town, saying that he was heading for Gijón, and that he did so with his head held high and despite the deadly dangers presented by the journey. He was proud of having done his duty and having acted throughout, with integrity, as a member of the CNT. That was in the early hours of 11 October.

Jose Maria Martinez’s body was discovered at 3.00 in the afternoon of the following day in Sotiello (Gijón). Cruel fate! It is worth, however, emphasising, that when he bade farewell to the comrades on the Central Revolutionary Committee in Oviedo, he was carrying a substantial sum of money, thousands of pesetas. When his corpse was found, however, there was not a penny in his pockets. Can anyone shed light on that?

Ramón Ǻlvarez Palomo (1984)

*****

José Maria Martinez, in the day of the gun by Victor Guillot Monroy

The corpse lay there, lizard-cold. It turned up on the railroad tracks, belly upwards, clutching a rifle and with a gunshot through the chest. That morning in Sotiello somebody could be heard announcing: “There’s a corpse up on the hill!” All the children raced to where the corpse lay. The tall figure made no impact on them. A well-built man he looked like a wounded whale dumped on the railroad tracks. The faint stench of death merely added to the curiosity of the children who found him. When they recognised his face, they then noticed his sardonic grin. And scarpered, shrieking: “It’s José Maria Martinez.”

The corpse lay there, lizard-cold. It turned up on the railroad tracks, belly upwards, clutching a rifle and with a gunshot through the chest. That morning in Sotiello somebody could be heard announcing: “There’s a corpse up on the hill!” All the children raced to where the corpse lay. The tall figure made no impact on them. A well-built man he looked like a wounded whale dumped on the railroad tracks. The faint stench of death merely added to the curiosity of the children who found him. When they recognised his face, they then noticed his sardonic grin. And scarpered, shrieking: “It’s José Maria Martinez.”

Gijón’s most important CNT leader of the October 1934 revolution had been murdered in the early hours.

José Maria Martinez was born in 1884 in Cangas de Onis. When his family moved to Gijón, Jose Maria began work as a bottle boy at the La Industria Glass Plant before becoming a steelworker. His trade union activities would have begun at the turn of the century when ‘El Despertar del minero‘ [The Miner’s Awakening}, the first anarchist Asturian miners’ union, was launched in Langreo with José Maria Martinez as its secretary. At that time he was a victim of political persecution and used the alias José Riestra.

Although his wife and two children lived in Gijón, he was the instigator of various strikes in Langreo and Nieves. The former, in 1912, targeted the Duro-Felguera Company, after the former refused workers a say in framing its internal regulations, and after the bosses refused a pay increase. By the end of that year, with the dispute in its fifth month, José Riestra was calling for sabotage, should the workers be beaten. The strike lasted nine months

During the 1914 strike in the Langreo valley —prompted by the soaring cost of bread — waving a pistol he harangued the crowd in La Felguera, confronted the Civil Guards, broke through the military cordon and led the attack on Enrique Menendez’s bakery.

José Maria Martinez was a man of action who thought as much about dicing with death as he did about smoking a cigarette. When the time came to squeeze the trigger of his 9 millimetre largo his hand never shook. Every time he was released from prison he would tell his wife that the purpose of his struggle was to make things better, not in the here-and-now but for future generations. He was fighting for the future, not for specific individuals.

By 1919 he was a prominent CNT leader and at the CNT’s national congress, José Maria Martinez and Manuel Álvarez represented 3,342 members from the steel-working sector in Gijón. When the idea of amalgamating with the UGT was mooted, Martinez called for the entire Spanish proletariat to be united in a single body so that the renovation of Spain might be carried through more easily. As far as this prominent Asturian CNT leader was concerned, it was the workers who were yearning for unity while the leaders of the two organisations were rejecting it.

José Maria Martinez, a disciple of Eleuterio Quintanilla, was a lobbyist for the Alianza Obrera (Worker Alliance), the body that paved the way for the 1934 revolution in Asturias — having talked his own people and the Asturian socialists around. His signature was on the Alliance agreement.

The earliest overtures aimed at a Worker Alliance came from the CNT leaders jailed in Gijón’s El Coto prison after the failure of the CNT’s national uprising in December 1933. Segundo Blanco, José Maria Martinez, Avelino González Mallada and Horacio Argüelles, among others, wrote to the CNT’s regional plenum proposing an alliance with the UGT. The motion was carried and a commission set up (with José Maria Martinez as a member) tasked with contacting the UGT and the Asturian Socialist Federation. The Alliance was signed on 31 March and its aims were: “1. Openly to combat fascism which is trying to foist its typical system of repression upon the people by doing away with class struggle organisations and those few established freedoms and rights in the country. 2. To mount broad efforts in opposition to any warlike intent, whether in relation to the nations of the continent of Europe or to the colonial issue in Africa.”

From La Nueva España, 13 October 2004.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.