I failed to realise that the 19th instalment of The Originals last week marked the 100th song to be, erm, covered in the series (remember, the first part included ten songs, part 2 featured six). Since it can be argued that the story of Bitter Sweet Symphony wasn’t really a tale of an original and its cover, we enter the second century of the series with a South African song with a most remarkable history (and pardon the length of the entry; it’s worth reading anyhow, I hope), as well as the originals of the Kingsmen‘s Louie Louie, Glen Campbell‘s By The Time I Get To Phoenix, Deep Purple‘s Hush and the bizarre Tiny Tim‘s Tip Toe Through The Tulips.

.

Solomon Linda’s Original Evening Birds – Mbube.mp3

The Weavers – Wimoweh.mp3

Miriam Makeba – The Lion Song (Mbube).mp3

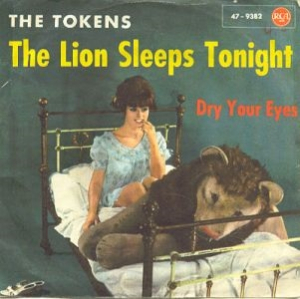

The Tokens – The Lion Sleeps Tonight.mp3

Pete Seeger – Wimoweh (live).mp3

Soweto Gospel Choir – Mbube.mp3

One of the most foul stories of songwriting theft must be the story of Mbube (the song known more widely as The Lion Sleeps Tonight or Wimoweh), with even the venerable Pete Seeger involved in the deceit; though he comes out of it a lot better than others.

One of the most foul stories of songwriting theft must be the story of Mbube (the song known more widely as The Lion Sleeps Tonight or Wimoweh), with even the venerable Pete Seeger involved in the deceit; though he comes out of it a lot better than others.

The man who wrote and first recorded it, Solomon Linda, died virtually penniless, having been duped into selling the rights to the song for a pittance to the Italian-born South African record label owner Eric Gallo. Gallo pocketed the royalties of the prodigious South African sales, in return allowing Linda to work in his packing plant. Apart from performing on stage in South Africa, where he was a musical legend in the townships, Linda worked there until his death at 53 in 1962 — nine years after Seeger and the Weavers had a US #6 hit with it, and a year after The Tokens scored a huge hit with the song in a reworked version. No laws were broken in this deplorable story of plagiarism, but the rules of ethics and common decency certainly were.

Solomon Linda

Mbube was introduced to American music by Pete Seeger, who adapted a fairly faithful version of the song. Still, Seeger didn’t even transcribe the word “uyiMbube” properly, even though he had received a record of the song (from the great music historian Alan Lomax), which had a label stating the title on it. And surely it should have been possible to research a song which sold a 100,000 copies in South Africa, especially if Alan Lomax is your friend, in such a way as not to render “uyiMbube” as “wimoweh”.

Seeger later pleaded ignorance about the intricacies of music publishing, and, to his credit, deeply regretted not insisting firmly enough that Linda be given the songwriting credit. He had sent his initial arrangers’s fee of $1,000 to Linda and insisted that the song’s publishers, TRO, should keep sending royalties to the South African. Apparently they periodically did so, though Linda’s widow had little idea where the money — hardly riches (about $275 per quarter in the early ’90s) — came from. Some family members say the payments started only in the 1980s. Whatever the case, neither Linda nor Seeger were credited for the song now known as Wimoweh. The credit went to Paul Campbell, a pseudonym used by TRO owner Harry Richmond to copyright the many public-domain folk songs which TRO published.

The Tokens’ version took even greater liberties. But this time nobody could claim ignorance because Miriam Makeba, who grew up with the song, released it in the US in 1960, a year before The Tokens’ version was created, as Mbube, or The Lion (mbube means lion). It is fair to say that George David Weiss, who rearranged the song for The Tokens, at their request, should not be denied his songwriter credit (that would be the same Weiss who co-wrote Elvis’ Can’t Help Falling In Love with mafia associates and RCA producers Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore ). Weiss dismantled and restructured the song, turning a very African song into an American novelty pop song. As so often, the future classic was first relegated to the b-side; a disc jockey, not impressed with the a-side, flipped over the single and so created a massive hit.

The Tokens’ version took even greater liberties. But this time nobody could claim ignorance because Miriam Makeba, who grew up with the song, released it in the US in 1960, a year before The Tokens’ version was created, as Mbube, or The Lion (mbube means lion). It is fair to say that George David Weiss, who rearranged the song for The Tokens, at their request, should not be denied his songwriter credit (that would be the same Weiss who co-wrote Elvis’ Can’t Help Falling In Love with mafia associates and RCA producers Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore ). Weiss dismantled and restructured the song, turning a very African song into an American novelty pop song. As so often, the future classic was first relegated to the b-side; a disc jockey, not impressed with the a-side, flipped over the single and so created a massive hit.

Peretti and Creatore claimed co-writing credit and the rights to the song, deciding that Mbube was an old African folk song and therefore in the public domain. They might well have thought so in good faith, but a minimum of research would have established the facts, even before the age of Google. Or perhaps not: they pulled the same stunt with Miriam Makeba’s Click Song (the clicking is a distinctive sound in the Xhosa language), which the Tokens released as Bwanina. They got away with that, because Makeba’s number was based on an old folk song. Not so with The Lion Sleeps Tonight, to which Gallo, the record label owner from South Africa, had asserted his US rights in 1952 and then sold it to TRO. A whole lot of wheeling and dealing took place, with the upshot that the credit now included TRO’s fictitious Paul Campbell. Again, Linda was left out in the cold.

It was only at the beginning of the present decade that Linda’s family took legal action, and that only after Richmond, Weiss and the mafia pals started to wrangle about the ownership to the song. Solomon Linda’s family eventually won a settlement which entitles them to future royalties and a lump sum for royalties going back to 1987, largely due to an extensive Rolling Stone exposé by South African one-book wonder novelist Rian Malan. By some estimates, Mbube/Wimoweh/The Lion Sleeps Tonight has accrued royalties in the region of $15 million. Linda’s family initially sued Disney for $1.5 million for the song’s use in The Lion King – happily they are now due royalties from other versions. Malan and the family’s lawyers are still trying to find versions of the song against which to claim royalties.

Here’s the kicker: Solomon Linda was quite delighted at the international success of his song; he didn’t realise that he should have received something for it — even if that something was just an acknowledgment that he wrote the song.

Read the full story of Mbube.

Also recorded by: Karl Denver (1962), Henri Salvador (as Le lion est mort ce soir, 1962), Roger Whittaker (1967), The New Christy Minstrels (1965), Eric Donaldson (1971), Robert John (1972), Dave Newman (1972), Ras Michael and the Sons of Negus (as Rise Jah Jah Children, 1974), Brian Eno (1975), Flying Pickets (1980), Roboterwerke (1981), Tight Fit (1981), The Nylons (1982), Hotline (1984), Sandra Bernhard (1988), They Might Be Giants with Laura Cantrell (as The Guitar [The Lion Sleeps Tonight], 1990), R.E.M. (as The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite, 1993), Nanci Griffith (1993), Lebo M (1994), Steve Forbert (1994), *NSYNC (1997), Helmut Lotti (2000), Laurie Berkner (2000) a.o.

.

Billy Joe Royal – Hush.mp3

Deep Purple – Hush.mp3

In Volume 19 we looked at Joe South’s original of Rose Garden. South enjoyed chart success himself with Games People Play, and wrote a couple of hits for Billy Joe Royal, including Royal’s signature hit Down In The Boondocks (1965, originally intended for Gene Pitney) and Hush (1967). Royal — it is his real name — had a country background, though one influenced by the soul stylings of Sam Cooke and Ray Charles. He performed with the country singer likes of Jerry Reed and George Stevens, but aimed for a pop audience. For a while he succeeded, but when his pop star waned, he successfully crossed back into traditional country. His final pop charts entry, a 1978 version of Under The Boardwalk which peaked at #82, was followed in 1985 by his first country charts entry (Burned Like A Rocket, #10).

In Volume 19 we looked at Joe South’s original of Rose Garden. South enjoyed chart success himself with Games People Play, and wrote a couple of hits for Billy Joe Royal, including Royal’s signature hit Down In The Boondocks (1965, originally intended for Gene Pitney) and Hush (1967). Royal — it is his real name — had a country background, though one influenced by the soul stylings of Sam Cooke and Ray Charles. He performed with the country singer likes of Jerry Reed and George Stevens, but aimed for a pop audience. For a while he succeeded, but when his pop star waned, he successfully crossed back into traditional country. His final pop charts entry, a 1978 version of Under The Boardwalk which peaked at #82, was followed in 1985 by his first country charts entry (Burned Like A Rocket, #10).

Hush was not a big hit for Royal, peaking at #52. But it became the first hit for hairy hard rock legends Deep Purple, in 1968 — even though initially nitially the group was not really interested in the song. Since then, Hush has been recorded in various styles, most of them taking as their template Deep Purple’s version rather than Royal’s gospel-tinged original which evokes the source of South’s inspiration for the song: a spiritual which included the line “Hush, I thought I heard Jesus calling my name.”

Also recorded by: Johnny Hallyday (as Mal, 1967), I Colours (1968), Merrilee Rush & Turnabouts (1968), The Love Affair (1968), Jimmy Frey (1969), Funky Junction (1973), Deep Purple (1985), Milli Vanilli (1988), Killdozer (1989), Gotthard (1992), Kula Shaker (1997)

.

Richard Berry & The Pharoahs – Louie Louie.mp3

Richard Berry & The Pharoahs – Louie Louie.mp3

The Kingsmen – Louie Louie.mp3

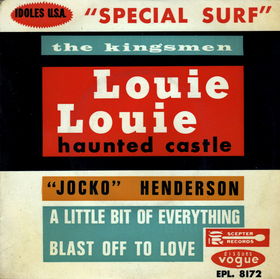

There are people who like to designate the Kingsmen’s 1963 version of Louie Louie as the first ever punk song. One can see why: it’s production is shambolic, the drummer is rumoured to be swearing in the background, the singer’s diction is non-existence, the modified lyrics were investigated by the FBI for lewdness (the feds found nothing incriminating, not even the line which may or may not have been changed from “it won’t be long me see me love to “stick my finger up the hole of love”), and by the time the song became a hit – after a Boston DJ played in a “worst songs ever” type segment — the band had broken up and toured in two incarnations.

Originally it was a regional hit in 1957 for an R&B singer named Richard Berry, who took inspiration from his namesake Chuck and West Indian music. In essence, it’s a calypso number of a sailor telling the eponymous barman about the girl he loves. It was originally released as a b-side, but quickly gained popularity on the West Coast. It sold 40,000 copies, but after a series of flops Berry momentarily retired from the recording business, selling the rights to Louie Louie for $750. In the meantime, bands continued to include the song in their repertoire. It was a 1961 version by Rockin’ Robin Roberts & the Fabulous Wailers which provided the Kingsmen with the prototype for their cover.

It is said that Louie Louie has been covered at least 1,500 times. It has also woven itself into the fabric of American culture, having been referenced in several movies, as diverse as Animal House and Mr Holland’s Opus. In the terribly underrated 1990 roadtrip film Coupe de Ville, three brothers (including a young Patrick Dempsey) have an impassioned debate about whether Louie Louie is a sea shanty or a song about sex.

Also recorded by: Rockin’ Robin Roberts (1961), Paul Revere & The Raiders (1963), Beach Boys (1963), The Kinks (1964), Joske Harry’s & The King Creoles (1964), Otis Redding (1964), The Invictas (1965), Jan & Dean (1965), The Ventures (1965), The Sandpipers (1966), Swamp Rats (1966), The Ad-Libs (1966), The Sonics (1966), The Troggs (1966), Friar Tuck (1967), The Tams (1968), Toots and the Maytals (1972), Flash Cadillac & the Continental Kids (1973), Skid Row (1976), The Flamin’ Groovies (1977), The Clash (live bootleg, 1977), The Kids (1980), Joan Jett & the Blackhearts (1981), Barry White (1981), Stanley Clarke & George Duke (1981), Maureen Tucker (1981), Black Flag (1981), Motörhead (1984), Lyres (1987), The Fat Boys (1988), The Purple Helmets (1988), Young MC (1990), Massimo Riva (as Lui Luigi, 1992), Pow Wow (1992), The Outcasts (1993), Iggy Pop (1993), Robert Plant (1993), The Queers (1994), The Stingray (1996), The Alarm Clocks (2000), Mazeffect (2003), Angel Corpus Christi (2005) a.o.

.

Nick Lucas – Tip Toe Through The Tulips With Me.mp3

Tiny Tim – Tip Toe Through The Tulips.mp3

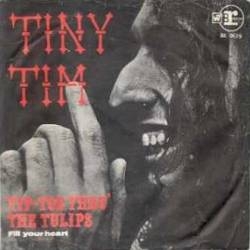

Whatever mind-altering substance it was that possessed the record buying public to turn Tiny Tim’s bizarre rendition of Tip-Toe Through The Tulips into an international hit, I want some. Usually a baritone, Tiny Tim sang the old standard in a bizarre falsetto which he had “discovered” by accident when singing along to a song on the radio as a young man in the early ’50s. Somehow he built up a loyal cult following with that falsetto shtick, ultimately leading to his novelty hit (possibly aided by his cryranoesque physiognomy) following its performance on the comedy variety show Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In.

Whatever mind-altering substance it was that possessed the record buying public to turn Tiny Tim’s bizarre rendition of Tip-Toe Through The Tulips into an international hit, I want some. Usually a baritone, Tiny Tim sang the old standard in a bizarre falsetto which he had “discovered” by accident when singing along to a song on the radio as a young man in the early ’50s. Somehow he built up a loyal cult following with that falsetto shtick, ultimately leading to his novelty hit (possibly aided by his cryranoesque physiognomy) following its performance on the comedy variety show Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In.

But Tiny Tim, known to his mother as Herbert Khaury, was more than a bit of a court jester. In his real life, which ended in 1996 at the age of 64, he was a serious student of American music history. He didn’t do Tip-Toe as a parody but as a tribute to the song’s original performer, Nick Lucas. Indeed, Lucas sang it at Khoury’s 1969 wedding to one Miss Vicky on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show (Video of Tiny Tim and Miss Vicky crooning on the show).

But Tiny Tim, known to his mother as Herbert Khaury, was more than a bit of a court jester. In his real life, which ended in 1996 at the age of 64, he was a serious student of American music history. He didn’t do Tip-Toe as a parody but as a tribute to the song’s original performer, Nick Lucas. Indeed, Lucas sang it at Khoury’s 1969 wedding to one Miss Vicky on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show (Video of Tiny Tim and Miss Vicky crooning on the show).

Nick Lucas, known in his prime as “The Crooning Troubadour” and later as “the grandfather of the jazz guitar”, topped the charts with the song — written in 1926 by Joe Burke and Al Dubin — for ten weeks in 1929 on the back of its inclusion in the early colour film Gold Diggers Of Broadway (video).

Also recorded by: Jean Goldkette (1929), Johnny Marvin (1929), Roy Fox (1929) a.o.

.

Johnny Rivers – By The Time I Get To Phoenix.mp3

Glen Campbell – By The Time I Get To Phoenix.mp3

Isaac Hayes – By The Time I Get To Phoenix (full ).mp3

Johnny Rivers is mostly remembered as the ’60s exponent of rather good rock & roll covers, especially on his Live At The Whiskey A Go Go LP. He was also the owner of the record label which released the music of The 5th Dimension. In that capacity, Rivers gave the budding songwriter Jimmy Webb his first big break, having The 5th Dimension record Webb’s song Up, Up And Away and thereby giving Webb (and the group and the label) a first big hit in 1967. By The Time I Get To Phoenix is another Webb composition, and this one Rivers recorded himself first for his Changes album in 1966 (when Webb was only 19!).

Johnny Rivers is mostly remembered as the ’60s exponent of rather good rock & roll covers, especially on his Live At The Whiskey A Go Go LP. He was also the owner of the record label which released the music of The 5th Dimension. In that capacity, Rivers gave the budding songwriter Jimmy Webb his first big break, having The 5th Dimension record Webb’s song Up, Up And Away and thereby giving Webb (and the group and the label) a first big hit in 1967. By The Time I Get To Phoenix is another Webb composition, and this one Rivers recorded himself first for his Changes album in 1966 (when Webb was only 19!).

Rivers’ version made no impact, nor did a cover by Pat Boone. The guitarist on Boone’s version, however, picked up on the song and released it in 1967. Glen Campbell scored a massive hit with the song, even winning two Grammies for it. In quick succession, Campbell completed a trilogy of geographically-themed songs by Webb, with the gorgeous Wichita Lineman (written especially for Campbell) and the similarly wonderful Galveston.

Another seasoned session musician took Phoenix into a completely different direction (if you will pardon the unintended pun). Isaac Hayes had heard the song, and decided to perform it as the Bar-Keys’ guest performer at Memphis’ Tiki Club, a soul venue. He started with a spontaneous spoken prologue, explaining in some detail why this man is on his unlikely journey. At first the patrons weren’t sure what Hayes was doing rapping over a repetitive chord loop. After a while, according to Hayes, they started to listen. At the end of the song, he said, there was not a dry eye in the house (“I’m gonna moan now…”). As it appeared on Ike’s 1968 Hot Buttered Soul album, the thing went on for 18 glorious minutes.

Another seasoned session musician took Phoenix into a completely different direction (if you will pardon the unintended pun). Isaac Hayes had heard the song, and decided to perform it as the Bar-Keys’ guest performer at Memphis’ Tiki Club, a soul venue. He started with a spontaneous spoken prologue, explaining in some detail why this man is on his unlikely journey. At first the patrons weren’t sure what Hayes was doing rapping over a repetitive chord loop. After a while, according to Hayes, they started to listen. At the end of the song, he said, there was not a dry eye in the house (“I’m gonna moan now…”). As it appeared on Ike’s 1968 Hot Buttered Soul album, the thing went on for 18 glorious minutes.

Also recorded by: Pat Boone (1967), Floyd Cramer (1967), Vikki Carr (1968), Roger Miller (1968), Andy Williams (1968), Eddy Arnold (1968), Conway Twitty (1968), Marty Robbins (1968), The Lettermen (1968), David Houston (1968), Tony Mottola (1968), Al Wilson (1968), The Main Attraction (1968), King Curtis (1968), Jack Jones (1968), Julius Wechter & Baja Marimba Band (1968), Ace Cannon (1968), Harry Belafonte (1968), Jack Greene (1968), Jim Nabors (1968), John Davidson (1968), Four Tops (1968), Ray Conniff (1968), Frankie Valli (1968), Larry Carlton (1968), Johnny Mathis (1968), Frank Sinatra (1968), Dean Martin (1968), The Intruders (1968), Bobby Goldsboro (1968), Ray Price (1968), Engelbert Humperdinck (1968), Claude François (as Le temps que j’arrive à Marseille, 1969), A.J. Marshall (1969), Mantovani (1969), José Feliciano (1969), Nat Stuckey (1969), The Mad Lads (1969), William Bell (1969), Young-Holt Unlimited (1969), Erma Franklin (1969), Dorothy Ashby (1969), Nancy Wilson (1969), Wayne McGhie & the Sounds of Joy (1970), Winston Francis (1970), Mongo Santamaría (1970), The Ventures (1970), Wanda Jackson (1970), Fabulous Souls (1971), The Wip (1971), New York City (1973), The Escorts (1973), Susannah McCorkle (1986), Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds (1986), Eric Miller & His Orchestra (1991), Reba McIntyre (1995), Jimmy Webb (1996), Detroit Underground (1997), Heather Myles (2002), Thelma Houston (2007), Maureen McGovern (2008) a.o.

.

More Originals

When one wallows in misery, it is good to know that others are feeling just as badly. B.J. Thomas wants his sorrow over a break-up validated by knowing about the romantic distress of others; a union of broken hearts standing together in spiritual solidarity. B.J. is calling for that fraternity through the medium of song. So if he is still wallowing, this post might be just what he needs while he misses his baby. “So please play for me a sad melody, so sad that it makes everybody cry; a real hurtin’ song about a love that’s gone wrong, ’cause I don’t want to cry all alone.” Lyrics Morrissey would have killed for.

When one wallows in misery, it is good to know that others are feeling just as badly. B.J. Thomas wants his sorrow over a break-up validated by knowing about the romantic distress of others; a union of broken hearts standing together in spiritual solidarity. B.J. is calling for that fraternity through the medium of song. So if he is still wallowing, this post might be just what he needs while he misses his baby. “So please play for me a sad melody, so sad that it makes everybody cry; a real hurtin’ song about a love that’s gone wrong, ’cause I don’t want to cry all alone.” Lyrics Morrissey would have killed for. Alas, poor Richard Hawley. Earlier in this series he went to a popular hang-out in a futile bid to pull (

Alas, poor Richard Hawley. Earlier in this series he went to a popular hang-out in a futile bid to pull ( Here the singer was responsible for the break-up and desperately regrets it by way of cliché: “I didn’t mean to hurt you, but I know that in the game of love you reap what you sow.” She is proposing a reconciliation, but seems to understand that this may be a hope to far. Still, she insistently and repeatedly articulates her petition: “And I wish on all the rainbows that I see; I wish on all the people we’ve ever been; and I’m hopin’ on all the days to come and days to go, and I’m hopin’ on days of lovin’ you. So I’m wishing on a star, to follow where you are.”

Here the singer was responsible for the break-up and desperately regrets it by way of cliché: “I didn’t mean to hurt you, but I know that in the game of love you reap what you sow.” She is proposing a reconciliation, but seems to understand that this may be a hope to far. Still, she insistently and repeatedly articulates her petition: “And I wish on all the rainbows that I see; I wish on all the people we’ve ever been; and I’m hopin’ on all the days to come and days to go, and I’m hopin’ on days of lovin’ you. So I’m wishing on a star, to follow where you are.” In the most beautiful and moving of all the beautiful and moving songs here, Rosie had been maltreated by love before, as we learn in the song’s punchline. Now the person who healed her damaged heart is gone too, pulling the rug from under Rosie’s feet. “I’m wandering, I’m crawling, I’m two steps away from falling – I just can’t seem to get around. I’m heavy, I’m weary, I’m not thinking clearly. I just can’t seem to find solid ground since you’ve been around.”

In the most beautiful and moving of all the beautiful and moving songs here, Rosie had been maltreated by love before, as we learn in the song’s punchline. Now the person who healed her damaged heart is gone too, pulling the rug from under Rosie’s feet. “I’m wandering, I’m crawling, I’m two steps away from falling – I just can’t seem to get around. I’m heavy, I’m weary, I’m not thinking clearly. I just can’t seem to find solid ground since you’ve been around.” About as beautiful as Rosie Thomas’ track, fellow songbird Kate Walsh’s song protests that the object of her desire should make himself scarce because just seeing him opens up still raw wounds. “I’ll fall again if I see your face again, my love, and I’ve done all my crying for you love.” So meeting him again, with his antics such as rolling his blue eyes at her, will break her heart all over again. She wants to forget him, because “I cannot be in matrimony with a dream of love”.

About as beautiful as Rosie Thomas’ track, fellow songbird Kate Walsh’s song protests that the object of her desire should make himself scarce because just seeing him opens up still raw wounds. “I’ll fall again if I see your face again, my love, and I’ve done all my crying for you love.” So meeting him again, with his antics such as rolling his blue eyes at her, will break her heart all over again. She wants to forget him, because “I cannot be in matrimony with a dream of love”. It has been a while since the woman left poor Joseph, and he is depressed. “The plants have died, my hair has grown from the thought of you coming home.” He gets by through the consumption of alcohol, which is never a good idea in his mental condition. And in between he writes her letters which “I won’t send, except for across the floor” (what a fantastic line). Now and then he dreams of happier times, with her in his arms, but then the image of bliss turns to abrupt dread with “a smile that explodes” — again, wonderful imagery — “I could never understand”.

It has been a while since the woman left poor Joseph, and he is depressed. “The plants have died, my hair has grown from the thought of you coming home.” He gets by through the consumption of alcohol, which is never a good idea in his mental condition. And in between he writes her letters which “I won’t send, except for across the floor” (what a fantastic line). Now and then he dreams of happier times, with her in his arms, but then the image of bliss turns to abrupt dread with “a smile that explodes” — again, wonderful imagery — “I could never understand”. If B.J. Thomas had chosen to be more precise in his instruction, he may well have specified that he wanted a Smokey song to be played, because nobody does broken-heartedness the way Smokey Robinson does (even if here, the lyrics aren’t his). The tune is a cheerful, upbeat affair. Smokey sounds like he has no care in the world. But, as we know from past experience, in situations of heartache, Smokey pretends to be the life a party, putting on an out-of-place smile, masquerading outside while inside is heart is breaking. So the melody is deceiving us: Smokey is desperate to see his love again. “I would go anywhere. There’s nothing I wouldn’t do, just to see her again” and “hold her in my arms again, one more time”.

If B.J. Thomas had chosen to be more precise in his instruction, he may well have specified that he wanted a Smokey song to be played, because nobody does broken-heartedness the way Smokey Robinson does (even if here, the lyrics aren’t his). The tune is a cheerful, upbeat affair. Smokey sounds like he has no care in the world. But, as we know from past experience, in situations of heartache, Smokey pretends to be the life a party, putting on an out-of-place smile, masquerading outside while inside is heart is breaking. So the melody is deceiving us: Smokey is desperate to see his love again. “I would go anywhere. There’s nothing I wouldn’t do, just to see her again” and “hold her in my arms again, one more time”. While our other friends in this post have taken to despondency, dreaming, drinking, and descending into despair, Grohl is taking action before anything can happen. Anticipating that she is leaving him, he psyches himself into dumped mode and pledges to become a stalker. “I cannot be without you, matter of fact. I’m on your back”. Just to be sure she gets the sinister message he repeats: “I’m on your back.” And once more for creepy emphasis:“I’m on your back.” So, “if you walk out on me, I’m walking after you.” And with big Dave Grohl on her back, she won’t get very far.

While our other friends in this post have taken to despondency, dreaming, drinking, and descending into despair, Grohl is taking action before anything can happen. Anticipating that she is leaving him, he psyches himself into dumped mode and pledges to become a stalker. “I cannot be without you, matter of fact. I’m on your back”. Just to be sure she gets the sinister message he repeats: “I’m on your back.” And once more for creepy emphasis:“I’m on your back.” So, “if you walk out on me, I’m walking after you.” And with big Dave Grohl on her back, she won’t get very far. An appropriate title for today, even if the certain election of the misogynist homophobe Jacob Zuma is not a cause for extravagant optimism (though he can’t be much worse than Aids denialist, Mugabe-supporting Thabo Mbeki) . I’ve pushed the fare of Durban’s Farryl Purkiss in the past. This track, from his wonderful eponymously-titled 2006 album, is absolutely beautiful, in the singer-songwriter vein. He cites as an influence Elliott Smith, and at times sounds a lot like him, as well as the likes of Iron & Wine, Joe Purdy, Sufjan Stevens and Calexico. I have a hunch that Purkiss might have listened also to ’70s folkie Shawn Phillips (who, incidentally, now lives in South Africa) and the majestic Patty Griffin. I wrote about a Purkiss gig I saw in July 2007 (

An appropriate title for today, even if the certain election of the misogynist homophobe Jacob Zuma is not a cause for extravagant optimism (though he can’t be much worse than Aids denialist, Mugabe-supporting Thabo Mbeki) . I’ve pushed the fare of Durban’s Farryl Purkiss in the past. This track, from his wonderful eponymously-titled 2006 album, is absolutely beautiful, in the singer-songwriter vein. He cites as an influence Elliott Smith, and at times sounds a lot like him, as well as the likes of Iron & Wine, Joe Purdy, Sufjan Stevens and Calexico. I have a hunch that Purkiss might have listened also to ’70s folkie Shawn Phillips (who, incidentally, now lives in South Africa) and the majestic Patty Griffin. I wrote about a Purkiss gig I saw in July 2007 ( The same year, the lovely Josie Field had a radio hit (singles aren’t widely sold in SA, so charts are based on radio airplay) with this excellent song. I’m waiting for Natalie Imbruglia or somebody like that to cover it. Her debut album apparently sold 7,000 copies, which in her genre in South Africa is a very respectable number. With figures like that, I don’t know why anyone with Field’s obvious talent would bother to release albums in South Africa. (

The same year, the lovely Josie Field had a radio hit (singles aren’t widely sold in SA, so charts are based on radio airplay) with this excellent song. I’m waiting for Natalie Imbruglia or somebody like that to cover it. Her debut album apparently sold 7,000 copies, which in her genre in South Africa is a very respectable number. With figures like that, I don’t know why anyone with Field’s obvious talent would bother to release albums in South Africa. ( A real South African classic from 1986 which I think had some influence on the anti-apartheid struggle by way of conscientising young white South Africans. The song is about apartheid-era president PW Botha’s antics and features the strains of the then-banned struggle hymn Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrica. Strangely the state-owned radio stations played Weeping prodigiously. Songs had been banned for much less (a year previously, all Stevie Wonder music was banned from the airwaves after the singer dedicated his Grammy to Nelson Mandela).

A real South African classic from 1986 which I think had some influence on the anti-apartheid struggle by way of conscientising young white South Africans. The song is about apartheid-era president PW Botha’s antics and features the strains of the then-banned struggle hymn Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrica. Strangely the state-owned radio stations played Weeping prodigiously. Songs had been banned for much less (a year previously, all Stevie Wonder music was banned from the airwaves after the singer dedicated his Grammy to Nelson Mandela). Juluka’s frontman Johnny Clegg — the “White Zulu” — did a great deal for the struggle by integrating himself into Zulu culture, with sincerity and respect for Zulu culture. His groups, first Juluka and then Savuka, where multi-racial at a time when that was virtually unheard of. I have seen many concerts by Clegg’s groups, including a fantastic one in London’s Kentish Town & Country Club. Invariably, these were incredibly energetic. As a live performer, Clegg was not far behind Springsteen. The highlight always 1981’s Impi, which would send the crowd wild, especially when Clegg did those high-kicking, floor-board shattering Zulu wardance moves.

Juluka’s frontman Johnny Clegg — the “White Zulu” — did a great deal for the struggle by integrating himself into Zulu culture, with sincerity and respect for Zulu culture. His groups, first Juluka and then Savuka, where multi-racial at a time when that was virtually unheard of. I have seen many concerts by Clegg’s groups, including a fantastic one in London’s Kentish Town & Country Club. Invariably, these were incredibly energetic. As a live performer, Clegg was not far behind Springsteen. The highlight always 1981’s Impi, which would send the crowd wild, especially when Clegg did those high-kicking, floor-board shattering Zulu wardance moves. Recently a contestant in South Africa’s Idols show was favourably compared to the late Brenda Fassie. Such compliments are not offered lightly, not by sensible people. Fassie was a superstar, throughout Africa. People have compared her to Madonna (minus Fassie’s drug abuse, violence, lapses into madness, financial difficulties, lesbian affairs, and premature death). The comparison flatters Madonna. Fassie was a superstar but yet still one with the people, of the people. She showed that talent and charisma trumps vacant beauty. Vuli Ndlela was Fassie’s huge dance hit from 1998, an infectious number that by force of sheer energy compensates for some regrettable production values.

Recently a contestant in South Africa’s Idols show was favourably compared to the late Brenda Fassie. Such compliments are not offered lightly, not by sensible people. Fassie was a superstar, throughout Africa. People have compared her to Madonna (minus Fassie’s drug abuse, violence, lapses into madness, financial difficulties, lesbian affairs, and premature death). The comparison flatters Madonna. Fassie was a superstar but yet still one with the people, of the people. She showed that talent and charisma trumps vacant beauty. Vuli Ndlela was Fassie’s huge dance hit from 1998, an infectious number that by force of sheer energy compensates for some regrettable production values. Despite rumours of an impending break-up, Freshlygrounds remain South Africa’s most popular group. The multi-ethnic group transcends boundaries of race and genre. The group’s first hit, 2002’s Castles In The Sky, is a good example of veering between genres. This remixed version received the airplay; the original is a slightly African-inflected pop song which Everything But The Girl might have sung. The superior remix adds to it a House feel which turns the song into a slow-burning dance track. (

Despite rumours of an impending break-up, Freshlygrounds remain South Africa’s most popular group. The multi-ethnic group transcends boundaries of race and genre. The group’s first hit, 2002’s Castles In The Sky, is a good example of veering between genres. This remixed version received the airplay; the original is a slightly African-inflected pop song which Everything But The Girl might have sung. The superior remix adds to it a House feel which turns the song into a slow-burning dance track. ( In 1984, artist and author of children’s books Niki Daly had one of the more bizarre South African hits with this song, doubtless inspired by the likes of Bowie, Roxy Music, Gary Numan and Thomas Dolby. A great slice of mid-80s new wave. Like so much of great South African songs, it made no impression on the international charts. At least one of his books, Not So Fast, Songololo, is a children’s book classic. Many of the Capetonian’s books published in the 1980s promoted interracial relations, thereby helping to instil a mindset among those who were then children (and are now young adults) that colour ought not be a social barrier.

In 1984, artist and author of children’s books Niki Daly had one of the more bizarre South African hits with this song, doubtless inspired by the likes of Bowie, Roxy Music, Gary Numan and Thomas Dolby. A great slice of mid-80s new wave. Like so much of great South African songs, it made no impression on the international charts. At least one of his books, Not So Fast, Songololo, is a children’s book classic. Many of the Capetonian’s books published in the 1980s promoted interracial relations, thereby helping to instil a mindset among those who were then children (and are now young adults) that colour ought not be a social barrier.  I have posted this before, and it proved a very popular song. When the link went dead, I received a few requests to please re-upload it. Memories, by a Cape Town-based songwriter of folk and gospel material, scored a lovely

I have posted this before, and it proved a very popular song. When the link went dead, I received a few requests to please re-upload it. Memories, by a Cape Town-based songwriter of folk and gospel material, scored a lovely

The moment Hilton Valentine’s distinctive guitar arpeggio kicks off House Of The Rising Sun, the song is instantly recognisable. It is now The Animals’ song, even though not wildly dissimilar previous versions by folkie Josh White, Nina Simone, and Bob Dylan preceded that by Eric Burdon and pals. Burdon has said that White’s version inspired the Animals’ version, but at other times he has credited the English folk singer Johnny Handle for the inspiration. Dylan, for his part, was miffed that people thought that he had covered the Animals’ version. Ironically, fellow folk-singer Dave Van Ronk has accused Dylan of “borrowing” his arrangement.

The moment Hilton Valentine’s distinctive guitar arpeggio kicks off House Of The Rising Sun, the song is instantly recognisable. It is now The Animals’ song, even though not wildly dissimilar previous versions by folkie Josh White, Nina Simone, and Bob Dylan preceded that by Eric Burdon and pals. Burdon has said that White’s version inspired the Animals’ version, but at other times he has credited the English folk singer Johnny Handle for the inspiration. Dylan, for his part, was miffed that people thought that he had covered the Animals’ version. Ironically, fellow folk-singer Dave Van Ronk has accused Dylan of “borrowing” his arrangement. The song itself is an American folk song of uncertain date, adapted from an old English tune said to go back to the 17th century. It used different lyrics, though those credited to Georgia Turner and Bert Martin in the ’30s formed the early basis for the version we now know best. Turner’s version featured here was recorded by the great musicologist Alan Lomax in 1937, when she was 16. The oldest known recording, by Clarence Tom Ashley with Gwen Foster, dates back to 1933, using different lyrics. The song was recorded under alternative titles — blues legend Leadbelly went for the title In New Orleans — before House Of The Rising Sun stuck. By the time Josh White recorded it, the lyrics had been changed so much that the best-known version now excludes Turner and Martin from the songwriting credit.

The song itself is an American folk song of uncertain date, adapted from an old English tune said to go back to the 17th century. It used different lyrics, though those credited to Georgia Turner and Bert Martin in the ’30s formed the early basis for the version we now know best. Turner’s version featured here was recorded by the great musicologist Alan Lomax in 1937, when she was 16. The oldest known recording, by Clarence Tom Ashley with Gwen Foster, dates back to 1933, using different lyrics. The song was recorded under alternative titles — blues legend Leadbelly went for the title In New Orleans — before House Of The Rising Sun stuck. By the time Josh White recorded it, the lyrics had been changed so much that the best-known version now excludes Turner and Martin from the songwriting credit. The story goes that in 1949 actor and cowboy-country singer Stuart Hamblen was hunting with John Wayne in a remote part of Texas when they happened upon an abandoned, crumbling hut, miles from the nearest road. Intrigued, they entered, finding the corpse of an old mountain man. Hamblen wrote the lyrics right there, on a sandwich bag. As a song about dying, Hamblen’s recording was upbeat yet poignant.

The story goes that in 1949 actor and cowboy-country singer Stuart Hamblen was hunting with John Wayne in a remote part of Texas when they happened upon an abandoned, crumbling hut, miles from the nearest road. Intrigued, they entered, finding the corpse of an old mountain man. Hamblen wrote the lyrics right there, on a sandwich bag. As a song about dying, Hamblen’s recording was upbeat yet poignant. Hamblen sang the song from the first person perspective. Rosemary Clooney in her 1954 hit version became a spectator to the man’s death, giving it a rather indecorous upbeat treatment. In Clooney’s version, it seems that the death of the man is a matter of gratification. The record-buying public didn’t mind: her version topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic (two concurrently released versions in Britain notwithstanding). In 1981 Welsh rock & roll revivalist Shakin’ Stevens (Shakey!) resurrected the dead man’s epitaph in similar bouncy fashion, also topping the UK charts.

Hamblen sang the song from the first person perspective. Rosemary Clooney in her 1954 hit version became a spectator to the man’s death, giving it a rather indecorous upbeat treatment. In Clooney’s version, it seems that the death of the man is a matter of gratification. The record-buying public didn’t mind: her version topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic (two concurrently released versions in Britain notwithstanding). In 1981 Welsh rock & roll revivalist Shakin’ Stevens (Shakey!) resurrected the dead man’s epitaph in similar bouncy fashion, also topping the UK charts. As for Stuart Hamblen, shortly after writing This Ole House he experienced a religious conversion at a Billy Graham rally, became a broadcaster of Christian material. Having lost as a Democrat congressional candidate in 1933, he ran as the Prohibition Party’s candidate for US president in 1952, picking up 72,949 sober votes.

As for Stuart Hamblen, shortly after writing This Ole House he experienced a religious conversion at a Billy Graham rally, became a broadcaster of Christian material. Having lost as a Democrat congressional candidate in 1933, he ran as the Prohibition Party’s candidate for US president in 1952, picking up 72,949 sober votes. Popular music is not brimming over with songs about the romantic pursuits of rodents. Willis Alan Ramsey got his break as a 19-year-old in 1972 when he stayed in the same Austin, Texas hotel as Leon Russell and Gregg Allman. Precociously, he knocked on their doors, introduced himself, and impressed them so much that they invited him to record at their respective studios. Ramsey eventually signed for the Shelter Records label which Russell co-owned. He made only one album (recorded in five different studios), and then became a songwriter of some renown instead. His songs have been recorded by the likes of Waylon Jennings, Jimmy Buffett, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Lyle Lovett and Shawn Colvin. The most successful of the songs on his poorly selling, self-titled album was intended as a novelty number — how can a song about rodent porn be otherwise? — written in 15 minutes.

Popular music is not brimming over with songs about the romantic pursuits of rodents. Willis Alan Ramsey got his break as a 19-year-old in 1972 when he stayed in the same Austin, Texas hotel as Leon Russell and Gregg Allman. Precociously, he knocked on their doors, introduced himself, and impressed them so much that they invited him to record at their respective studios. Ramsey eventually signed for the Shelter Records label which Russell co-owned. He made only one album (recorded in five different studios), and then became a songwriter of some renown instead. His songs have been recorded by the likes of Waylon Jennings, Jimmy Buffett, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Lyle Lovett and Shawn Colvin. The most successful of the songs on his poorly selling, self-titled album was intended as a novelty number — how can a song about rodent porn be otherwise? — written in 15 minutes. Many of our performers of lesser-known originals never hit the big time, especially when they wrote the successfully covered song (which goes some way to explaining why their originals aren’t better known). Rodney Crowell isn’t one of them. A successful country singer, especially in the alt-country genre headlined by Earle and Van Zandt, he is still churning out records. Among his country credentials is his former marriage to Roseanne Cash, and a recording (and reworking) with his ex-father-in-law of I Walk The Line. Some might include him in this series as progenitor of the Keith Urban hit Making Memories of Us. Not many would associate him with having written and first performed one of Bob Seger’s biggest hits.

Many of our performers of lesser-known originals never hit the big time, especially when they wrote the successfully covered song (which goes some way to explaining why their originals aren’t better known). Rodney Crowell isn’t one of them. A successful country singer, especially in the alt-country genre headlined by Earle and Van Zandt, he is still churning out records. Among his country credentials is his former marriage to Roseanne Cash, and a recording (and reworking) with his ex-father-in-law of I Walk The Line. Some might include him in this series as progenitor of the Keith Urban hit Making Memories of Us. Not many would associate him with having written and first performed one of Bob Seger’s biggest hits. Barbara Ann became one of the Beach Boys’ biggest hits at the same time as the Beatles released Rubber Soul. For the Beatles, December 1965 was a new beginning; for the Beach Boys, Barbara-Ann bookmarked the end of their surf pop era, appearing on the covers album Beach Boys Party! (which included three versions of Beatles songs), as Brian Wilson was already preparing the massively influential Pet Sounds.

Barbara Ann became one of the Beach Boys’ biggest hits at the same time as the Beatles released Rubber Soul. For the Beatles, December 1965 was a new beginning; for the Beach Boys, Barbara-Ann bookmarked the end of their surf pop era, appearing on the covers album Beach Boys Party! (which included three versions of Beatles songs), as Brian Wilson was already preparing the massively influential Pet Sounds. Barbara-Ann (it was originally hyphenated) had been a 1961 US #13 hit for The Regents, an American-Italian doo wop group from the Bronx. They went on to have only one more Top 30 hit, Runaround. Barbara-Ann — written by bandmember Chuck Fassert’s brother Fred for their eponymous sister —had been recorded as a demo by The Regents in 1959. When they couldn’t land a record contract, the group folded. A couple of years later, a group called The Consorts, which included a Regents’ member’s younger brother, dug out the demo and played it at auditions. One record company, Cousins, liked Barbara-Ann and released it — but not by the Consorts, but the Regents’ version. The Regents hurriedly reunited, and the song quickly became a local and then a national hit.

Barbara-Ann (it was originally hyphenated) had been a 1961 US #13 hit for The Regents, an American-Italian doo wop group from the Bronx. They went on to have only one more Top 30 hit, Runaround. Barbara-Ann — written by bandmember Chuck Fassert’s brother Fred for their eponymous sister —had been recorded as a demo by The Regents in 1959. When they couldn’t land a record contract, the group folded. A couple of years later, a group called The Consorts, which included a Regents’ member’s younger brother, dug out the demo and played it at auditions. One record company, Cousins, liked Barbara-Ann and released it — but not by the Consorts, but the Regents’ version. The Regents hurriedly reunited, and the song quickly became a local and then a national hit.

16th Street Baptist church that killed for young girls (earning the city the moniker Bombingham), an act that still outrages.

16th Street Baptist church that killed for young girls (earning the city the moniker Bombingham), an act that still outrages. Suspicious Minds was written by American Sound Studios in-house writer Mark James (whose real name was Francis Zambon), who also wrote hits such as It’s Only Love and Hooked On A Feeling for his friend, country singer BJ Thomas. The latter was also a UK hit for the vile Jonathan King. BJ Thomas was in line to record Suspicious Minds before the song was given to Elvis — who insisted on recording the song even when his manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker, threatened that he wouldn’t over the question of publishing rights (always an issue with Parker). Thomas went on to have a big hit that year anyway with Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head, and went on to record Suspicious Minds in 1970.

Suspicious Minds was written by American Sound Studios in-house writer Mark James (whose real name was Francis Zambon), who also wrote hits such as It’s Only Love and Hooked On A Feeling for his friend, country singer BJ Thomas. The latter was also a UK hit for the vile Jonathan King. BJ Thomas was in line to record Suspicious Minds before the song was given to Elvis — who insisted on recording the song even when his manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker, threatened that he wouldn’t over the question of publishing rights (always an issue with Parker). Thomas went on to have a big hit that year anyway with Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head, and went on to record Suspicious Minds in 1970. Elvis would record four more songs written or co-written by James: Always On My Mind (written originally, as noted in

Elvis would record four more songs written or co-written by James: Always On My Mind (written originally, as noted in  The influence on Elvis’ early music by the sounds of Rhythm & Blues on the one hand and country music on the other — Arthur Crudup and Hank Snow — is well known. A third profound influence was gospel. Here, too, Elvis drew from across the colour line. Often he was one of the few white faces at black church services (as a youth in Tupelo, he lived in a house designated for white families but located at the edge of a black township), but he also loved the white gospel/country sounds created by the likes of the Louvin Brothers — whose charmless sibling Ira once declined an approach by his fan Elvis, citing his reluctance to speak to the “white nigger”.

The influence on Elvis’ early music by the sounds of Rhythm & Blues on the one hand and country music on the other — Arthur Crudup and Hank Snow — is well known. A third profound influence was gospel. Here, too, Elvis drew from across the colour line. Often he was one of the few white faces at black church services (as a youth in Tupelo, he lived in a house designated for white families but located at the edge of a black township), but he also loved the white gospel/country sounds created by the likes of the Louvin Brothers — whose charmless sibling Ira once declined an approach by his fan Elvis, citing his reluctance to speak to the “white nigger”. Elvis’ biggest gospel hit was Crying In The Chapel, which had been written in 1953 by Artie Glenn for his son Darrell, who performed it in the country genre. The same year, the R&B band Sonny Til & the Orioles — progenitors of the doo wop style of the late ’50s and the first of a succession of bird-themed bandnames — scored a #11 hit with the song (around the same time, a pop version by June Valli reached #4). It was the Orioles’ recording from which Elvis drew inspiration in his version, recorded shortly after he returned from the army in 1960. It was not released, at Tom Parker’s command, because Artie Glenn refused to share the rights to the song with the cut-throat publishing company of Elvis repertoire, Hill & Range. And with good reason, for the song continued to be a hit by several artists. Eventually Hill & Range secured the ownership. When Crying In The Chapel was eventually released in 1965, it was not only a US hit (his first top 10 single in two years), but also topped the UK charts.

Elvis’ biggest gospel hit was Crying In The Chapel, which had been written in 1953 by Artie Glenn for his son Darrell, who performed it in the country genre. The same year, the R&B band Sonny Til & the Orioles — progenitors of the doo wop style of the late ’50s and the first of a succession of bird-themed bandnames — scored a #11 hit with the song (around the same time, a pop version by June Valli reached #4). It was the Orioles’ recording from which Elvis drew inspiration in his version, recorded shortly after he returned from the army in 1960. It was not released, at Tom Parker’s command, because Artie Glenn refused to share the rights to the song with the cut-throat publishing company of Elvis repertoire, Hill & Range. And with good reason, for the song continued to be a hit by several artists. Eventually Hill & Range secured the ownership. When Crying In The Chapel was eventually released in 1965, it was not only a US hit (his first top 10 single in two years), but also topped the UK charts. Apparently written for Perry Como, The Wonder Of You was first recorded by Ray Peterson (he of Tell Laura I Love Her notoriety) in 1959, scoring a moderate hit with it. Peterson, who died in 2005, later liked to recount the story of how Elvis sought his permission to record the song. “He asked me if I would mind if he recorded The Wonder Of You. I said: ‘You don’t have to ask permission; you’re Elvis Presley.’ He said: ‘Yes, I do. You’re Ray Peterson.’” Not that Peterson owned the rights to the song, or was particularly famous for singing it.

Apparently written for Perry Como, The Wonder Of You was first recorded by Ray Peterson (he of Tell Laura I Love Her notoriety) in 1959, scoring a moderate hit with it. Peterson, who died in 2005, later liked to recount the story of how Elvis sought his permission to record the song. “He asked me if I would mind if he recorded The Wonder Of You. I said: ‘You don’t have to ask permission; you’re Elvis Presley.’ He said: ‘Yes, I do. You’re Ray Peterson.’” Not that Peterson owned the rights to the song, or was particularly famous for singing it. This song is probably most famous in its incarnation as Engelbert Humperdinck’s gaudy 1967 hit. In its original form, however, it is a country classic, written by Dallas Frazier. It was first recorded in 1965 and released the following year by that great purveyor of unintentionally funny songs and owner of the hickiest of hick accents, Ferlin Husky. His version was an album track; fellow country singer Jack Greene turned it into a hit in 1967. Elvis’ version, which appeared on the quite excellent 1971 Elvis Country album (after being a 1970 b-side of I Really Don’t Want To Know) and was a UK top 10 hit that year, certainly draws from the song’s country origins — though surely not from Husky’s original.

This song is probably most famous in its incarnation as Engelbert Humperdinck’s gaudy 1967 hit. In its original form, however, it is a country classic, written by Dallas Frazier. It was first recorded in 1965 and released the following year by that great purveyor of unintentionally funny songs and owner of the hickiest of hick accents, Ferlin Husky. His version was an album track; fellow country singer Jack Greene turned it into a hit in 1967. Elvis’ version, which appeared on the quite excellent 1971 Elvis Country album (after being a 1970 b-side of I Really Don’t Want To Know) and was a UK top 10 hit that year, certainly draws from the song’s country origins — though surely not from Husky’s original. Elvis did not particularly like Burning Love; if he didn’t record it under protest, he certainly was not going to spend much time on it. Where 16 years earlier he’d spend 30-odd takes on the spontaneous sounding Hound Dog (see

Elvis did not particularly like Burning Love; if he didn’t record it under protest, he certainly was not going to spend much time on it. Where 16 years earlier he’d spend 30-odd takes on the spontaneous sounding Hound Dog (see  Tom Parker got Elvis to sing this old standard because it was a favourite of his wife, Mrs Marie (!) Parker, in its 1940s version by country star Gene Austin. Written by Tin Pan Alley residents Lou Handman and Roy Turk in 1926, it was recorded by a swathe of artists in 1927. The first of these versions, by Ned Jakobs, was not released, so the honour of first released recording goes to one Charles Hart. The song first became a hit in the version by the improbably named Vaughn Deleath, “The Radio Girl”. Her take dates to June 13 (Hart’s was May 8). On August 5, 1927, the famed tenor Henry Burr put his voice to it. Many a crooner would follow, but some performers adapted the song to their genre. So it was with the Carter Family — the pioneers of country music who went on to produce June and Anita — whose quite lovely 1935 bluegrass version is barely recognisable, musically and even lyrically.

Tom Parker got Elvis to sing this old standard because it was a favourite of his wife, Mrs Marie (!) Parker, in its 1940s version by country star Gene Austin. Written by Tin Pan Alley residents Lou Handman and Roy Turk in 1926, it was recorded by a swathe of artists in 1927. The first of these versions, by Ned Jakobs, was not released, so the honour of first released recording goes to one Charles Hart. The song first became a hit in the version by the improbably named Vaughn Deleath, “The Radio Girl”. Her take dates to June 13 (Hart’s was May 8). On August 5, 1927, the famed tenor Henry Burr put his voice to it. Many a crooner would follow, but some performers adapted the song to their genre. So it was with the Carter Family — the pioneers of country music who went on to produce June and Anita — whose quite lovely 1935 bluegrass version is barely recognisable, musically and even lyrically. Featured here is not the studio version which those who don’t already have it don’t really need. What they need is the laughing version from one of his 1969 Vegas gigs. The conventional story has it that Elvis, probably amphetamine-addled, was cracking up at the high-pitched singing of a backing singer (said to be Cissy Houston, Whitney’s mother). An alternative story has it that after Elvis, as was his wont, “humorously” changed the lyrics from “Do you gaze at your doorstep and picture me there” to “Do you gaze at your bald head and wish you had hair”, when he spotted a bald man in the audience, setting him off into a fit of laughter — and all the while the backing singer keeps going in a most gamely fashion.

Featured here is not the studio version which those who don’t already have it don’t really need. What they need is the laughing version from one of his 1969 Vegas gigs. The conventional story has it that Elvis, probably amphetamine-addled, was cracking up at the high-pitched singing of a backing singer (said to be Cissy Houston, Whitney’s mother). An alternative story has it that after Elvis, as was his wont, “humorously” changed the lyrics from “Do you gaze at your doorstep and picture me there” to “Do you gaze at your bald head and wish you had hair”, when he spotted a bald man in the audience, setting him off into a fit of laughter — and all the while the backing singer keeps going in a most gamely fashion. US cities has been the subject of lyrics more frequently — so the challenge here was to identify three top tunes that mention in the title neither the city nor its state, nor Mardi Gras, nor Bourbon Street nor the Latin Quarter (though one does so partly), nor houses of rising suns. So here we entertain ourselves with a trio of songs about a parade confrontation between “tribes” of African-American Mardi gras reveller; a love song for a prostitute (Steely Dan rocking the pedal steel!); and the tale of a hoofer (the version here was not featured in my recent

US cities has been the subject of lyrics more frequently — so the challenge here was to identify three top tunes that mention in the title neither the city nor its state, nor Mardi Gras, nor Bourbon Street nor the Latin Quarter (though one does so partly), nor houses of rising suns. So here we entertain ourselves with a trio of songs about a parade confrontation between “tribes” of African-American Mardi gras reveller; a love song for a prostitute (Steely Dan rocking the pedal steel!); and the tale of a hoofer (the version here was not featured in my recent  This is the fourth and final flute mix. I’m now officially fluted out. Again, many thanks for the suggestions made (if you hate the tracks by Cat Stevens, the Blues Project and Genesis, blame other people!). And for three installments I managed to say it, but I am a weak man. “One year, at band camp…”

This is the fourth and final flute mix. I’m now officially fluted out. Again, many thanks for the suggestions made (if you hate the tracks by Cat Stevens, the Blues Project and Genesis, blame other people!). And for three installments I managed to say it, but I am a weak man. “One year, at band camp…” Pam Grier’s song — which borrows from Stevie Wonder’s Fingertips Part2 — appeared first in the 1973 blaxploitation movie The Big Doll House (in which Grier played Coffy — Coffy! — an imprisoned women on a vigilante mission), and made a comeback almost a quarter of a century later on the rather good Jackie Brown soundtrack, which celebrated the blaxploitation genre. The flute is prominent and brilliant.

Pam Grier’s song — which borrows from Stevie Wonder’s Fingertips Part2 — appeared first in the 1973 blaxploitation movie The Big Doll House (in which Grier played Coffy — Coffy! — an imprisoned women on a vigilante mission), and made a comeback almost a quarter of a century later on the rather good Jackie Brown soundtrack, which celebrated the blaxploitation genre. The flute is prominent and brilliant. One of the most foul stories of songwriting theft must be the story of Mbube (the song known more widely as The Lion Sleeps Tonight or Wimoweh), with even the venerable Pete Seeger involved in the deceit; though he comes out of it a lot better than others.

One of the most foul stories of songwriting theft must be the story of Mbube (the song known more widely as The Lion Sleeps Tonight or Wimoweh), with even the venerable Pete Seeger involved in the deceit; though he comes out of it a lot better than others.

The Tokens’ version took even greater liberties. But this time nobody could claim ignorance because Miriam Makeba, who grew up with the song, released it in the US in 1960, a year before The Tokens’ version was created, as Mbube, or The Lion (mbube means lion). It is fair to say that George David Weiss, who rearranged the song for The Tokens, at their request, should not be denied his songwriter credit (that would be the same Weiss who co-wrote

The Tokens’ version took even greater liberties. But this time nobody could claim ignorance because Miriam Makeba, who grew up with the song, released it in the US in 1960, a year before The Tokens’ version was created, as Mbube, or The Lion (mbube means lion). It is fair to say that George David Weiss, who rearranged the song for The Tokens, at their request, should not be denied his songwriter credit (that would be the same Weiss who co-wrote  In Volume 19 we looked at Joe South’s original of Rose Garden. South enjoyed chart success himself with Games People Play, and wrote a couple of hits for Billy Joe Royal, including Royal’s signature hit Down In The Boondocks (1965, originally intended for Gene Pitney) and Hush (1967). Royal — it is his real name — had a country background, though one influenced by the soul stylings of Sam Cooke and Ray Charles. He performed with the country singer likes of Jerry Reed and George Stevens, but aimed for a pop audience. For a while he succeeded, but when his pop star waned, he successfully crossed back into traditional country. His final pop charts entry, a 1978 version of Under The Boardwalk which peaked at #82, was followed in 1985 by his first country charts entry (Burned Like A Rocket, #10).

In Volume 19 we looked at Joe South’s original of Rose Garden. South enjoyed chart success himself with Games People Play, and wrote a couple of hits for Billy Joe Royal, including Royal’s signature hit Down In The Boondocks (1965, originally intended for Gene Pitney) and Hush (1967). Royal — it is his real name — had a country background, though one influenced by the soul stylings of Sam Cooke and Ray Charles. He performed with the country singer likes of Jerry Reed and George Stevens, but aimed for a pop audience. For a while he succeeded, but when his pop star waned, he successfully crossed back into traditional country. His final pop charts entry, a 1978 version of Under The Boardwalk which peaked at #82, was followed in 1985 by his first country charts entry (Burned Like A Rocket, #10).

Whatever mind-altering substance it was that possessed the record buying public to turn Tiny Tim’s bizarre rendition of Tip-Toe Through The Tulips into an international hit, I want some. Usually a baritone, Tiny Tim sang the old standard in a bizarre falsetto which he had “discovered” by accident when singing along to a song on the radio as a young man in the early ’50s. Somehow he built up a loyal cult following with that falsetto shtick, ultimately leading to his novelty hit (possibly aided by his cryranoesque physiognomy) following its performance on the comedy variety show Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In.

Whatever mind-altering substance it was that possessed the record buying public to turn Tiny Tim’s bizarre rendition of Tip-Toe Through The Tulips into an international hit, I want some. Usually a baritone, Tiny Tim sang the old standard in a bizarre falsetto which he had “discovered” by accident when singing along to a song on the radio as a young man in the early ’50s. Somehow he built up a loyal cult following with that falsetto shtick, ultimately leading to his novelty hit (possibly aided by his cryranoesque physiognomy) following its performance on the comedy variety show Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In. But Tiny Tim, known to his mother as Herbert Khaury, was more than a bit of a court jester. In his real life, which ended in 1996 at the age of 64, he was a serious student of American music history. He didn’t do Tip-Toe as a parody but as a tribute to the song’s original performer, Nick Lucas. Indeed, Lucas sang it at Khoury’s 1969 wedding to one Miss Vicky on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show (

But Tiny Tim, known to his mother as Herbert Khaury, was more than a bit of a court jester. In his real life, which ended in 1996 at the age of 64, he was a serious student of American music history. He didn’t do Tip-Toe as a parody but as a tribute to the song’s original performer, Nick Lucas. Indeed, Lucas sang it at Khoury’s 1969 wedding to one Miss Vicky on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show ( Johnny Rivers is mostly remembered as the ’60s exponent of rather good rock & roll covers, especially on his Live At The Whiskey A Go Go LP. He was also the owner of the record label which released the music of The 5th Dimension. In that capacity, Rivers gave the budding songwriter Jimmy Webb his first big break, having The 5th Dimension record Webb’s song Up, Up And Away and thereby giving Webb (and the group and the label) a first big hit in 1967. By The Time I Get To Phoenix is another Webb composition, and this one Rivers recorded himself first for his Changes album in 1966 (when Webb was only 19!).

Johnny Rivers is mostly remembered as the ’60s exponent of rather good rock & roll covers, especially on his Live At The Whiskey A Go Go LP. He was also the owner of the record label which released the music of The 5th Dimension. In that capacity, Rivers gave the budding songwriter Jimmy Webb his first big break, having The 5th Dimension record Webb’s song Up, Up And Away and thereby giving Webb (and the group and the label) a first big hit in 1967. By The Time I Get To Phoenix is another Webb composition, and this one Rivers recorded himself first for his Changes album in 1966 (when Webb was only 19!). Another seasoned session musician took Phoenix into a completely different direction (if you will pardon the unintended pun). Isaac Hayes had heard the song, and decided to perform it as the Bar-Keys’ guest performer at Memphis’ Tiki Club, a soul venue. He started with a spontaneous spoken prologue, explaining in some detail why this man is on his unlikely journey. At first the patrons weren’t sure what Hayes was doing rapping over a repetitive chord loop. After a while, according to Hayes, they started to listen. At the end of the song, he said, there was not a dry eye in the house (“I’m gonna moan now…”). As it appeared on Ike’s 1968 Hot Buttered Soul album, the thing went on for 18 glorious minutes.

Another seasoned session musician took Phoenix into a completely different direction (if you will pardon the unintended pun). Isaac Hayes had heard the song, and decided to perform it as the Bar-Keys’ guest performer at Memphis’ Tiki Club, a soul venue. He started with a spontaneous spoken prologue, explaining in some detail why this man is on his unlikely journey. At first the patrons weren’t sure what Hayes was doing rapping over a repetitive chord loop. After a while, according to Hayes, they started to listen. At the end of the song, he said, there was not a dry eye in the house (“I’m gonna moan now…”). As it appeared on Ike’s 1968 Hot Buttered Soul album, the thing went on for 18 glorious minutes.

Recent Comments