The Sanders campaign has certainly sharpened the contradictions, hasn’t it? It’s been very clarifying to see Hillary Clinton and her surrogates running against single-payer and free college, with intellectual cover coming from Paul Krugman and Vox. Expectations, having been systematically beaten down for 35 years, must be beaten down further, whether it’s Hillary saying that to go to college one needs some “skin in the game,” or Rep. John Lewis reminding us that nothing is free in America. A challenge from the left has forced centrist Democrats to reveal themselves as proud capitalist tools.

Latest to step up is Paul Starr, co-founder of The American Prospect. Normally the dull embodiment of tepid liberalism, Starr has unleashed a redbaiting philippic— a frothing one, even, by his usual standards—aimed at Bernie Sanders. Sanders is no liberal, Starr reveals—he’s a socialist. He may call himself a democratic socialist to assure us that he’s no Bolshevik—Starr actually says this—but that doesn’t stop Starr from stoking fears of state ownership and central planning. Thankfully the word “gulag” doesn’t appear, but that was probably an oversight.

Starr does have one substantial point—Sanders’ tax proposals wouldn’t be up to financing a Scandinavian-style welfare state. Taxing the rich more could raise substantial revenue, but nowhere near enough. And part of the point of steepening the progressivity of the tax system is hindering great fortunes from developing and being passed on. A good part of the reason that CEO incomes have gone up so much since the early 1980s is that taxes on them have gone down; stiffen the tax on them, and there’s far less incentive to pay überbosses so much in the first place. It’s like taxing tobacco or carbon—you can raise revenue by doing it, but you’re also trying to make the toxic things go away.

But, really, you don’t need a Swedish or Danish tax structure to pay for free college tuition and single-payer health care, which are highly achievable first steps of a Sanderista political revolution. As I wrote back in 2010:

It would not be hard at all to make higher education completely free in the USA. It accounts for not quite 2% of GDP. The personal share, about 1% of GDP, is a third of the income of the richest 10,000 households in the U.S., or three months of Pentagon spending. It’s less than four months of what we waste on administrative costs by not having a single-payer health care finance system. But introduce such a proposal into an election campaign and you would be regarded as suicidally insane.

That last sentence turned out to be not a bad prophecy.

Starr really loses contact with earth when he writes about single-payer.* In one sense, this is surprising, since he wrote a fat book on the history of medicine in America, and, although it was 34 years ago, is presumably still familiar with the territory. But the pressures of a political campaign often dislodge an apologist’s higher cerebral functions. That’s the only plausible explanation for why he wrote this:

Sanders’ single-payer health plan shows the same indifference to real-world consequences. The plan calls for eliminating all patient cost sharing and promises to cover the full range of services, including long-term care. With health care running at 17.5 percent of gross domestic product, Sanders’ plan would sweep a huge share of economic activity into the federal government and invite that share to grow. Another way of looking at single payer is that it would make Washington the sole checkpoint, removing the incentive for anyone else—patients, providers, employers or state governments—even to monitor, much less hold back, excessive costs. It would leave no alternative except federal management of the health sector.

Where to start with this? Why, as a matter of principle, should patients “share costs”? They’re already paying for the services with their tax dollars. According to Hillary’s “skin-in-the-game” theory, forcing patients to pay up will reduce demand, thereby keeping spending down, but this is a brutal form of cost-control. Co-pays often force people to forego needed care, resulting in higher costs down the road, and more importantly, needless suffering. (See this Gallup poll, and references 6, 7, and 8 here.)

A far more effective form of cost control is having the government use its buying power to demand lower prices from hospitals and drug companies. That’s the way it works in civilized countries, though that fact looks to have passed Starr by, probably because he was too busy trying to make precisely the opposite, and wrong, argument: single-payer would “invite that share to grow” by “removing the incentive for anyone else…even to monitor, much less hold back, excessive costs.” Just what is wrong with “federal management of the health sector”? Medicare does it for the 0ver-65 portion of the population; it works very well and is enormously popular.

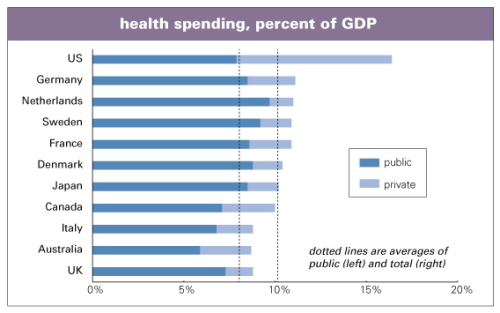

Starr cites the 17.5% of GDP we devote to health care without putting that figure into any reasonable context—the sort of move that is supposed to provoke a “gee-whiz” moment of surrender. Here’s an interesting graph based on data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a Paris-based quasi-official think tank for the world’s rich countries. It shows the share of GDP devoted to health care for a subset of the OECD’s 34 members, divided into public and private. (Put them together and you get the total.)

There are several striking features in this graph:

- Most striking of all is how far ahead of the pack the U.S. is: we spend 16.4% of GDP on health care, compared to a 10.1% average for all the other countries shown. (That’s the dotted vertical line on the right.) And recall that all those other countries cover almost their entire populations, unlike the U.S., where a tenth of the population is uninsured (and many of the insured have terrible coverage), with little change since the drop when Obamacare first took effect. (Gallup has 12% of the population uninsured, slightly higher than the Census Bureau, though with a similar trajectory of initial decline followed by flatlining.)

- Another striking, though less obvious, thing is that U.S. public spending alone, 7.9% of GDP, is just 0.1 point below the average of 8.0%. In other words, the government already spends as much as many other countries do while accomplishing far less. That 7.9% is also not much less than the entire health bill for Italy, Australia, and Britain, public and private combined.

- Yet another striking thing is the outlandishly large share of private spending on health care: 8.5% of GDP, more than four times the average of the other countries and almost three times Canada’s private share.

- Does all that spending produce better outcomes? Seems not: our life expectancy, 78.8 years, is three years shorter than the average of all the other countries.

So just about everything in Starr’s quoted mini-lecture about the real world is at odds with the real world.

There’s a perverse form of American exceptionalism circulating around the Clinton camp: just because things work in other countries doesn’t mean they can work here. As Hillary herself put it, “We are not Denmark. I love Denmark, but we are the United States of America.” True enough, but that has no bearing on why single-payer couldn’t work here. The only obstacles are political—elites, which include Hillary and Starr, don’t want it.

The rest of Starr’s piece is a highly unsubtle rant about socialism and how bad it is, even though Sanders isn’t really a socialist. That sort of thing may resonate with people who grew up during the Cold War—though not with all of us!—but it seems not to move the younger portion of the population, many of whom seem charmed by socialism. It’s not like capitalism has been treating them all that well. But Starr doesn’t want to hear about that.

Starr also finds the style of Sanders’ politics in bad taste:

Sanders is also doing what populists on both sides of the political spectrum do so well: the mobilization of resentment. The attacks on billionaires and Wall Street are a way of eliciting a roar of approval from angry audiences without necessarily having good solutions for the problems that caused that anger in the first place.

But people have a lot to resent—why shouldn’t it be mobilized politically? And free tuition and single-payer are pretty good solutions for some of those problems. Starr just doesn’t like them. Best leave the tuition issue to some vague, incomprehensible scheme (that apparently involves lots of work–study and online learning) and health care to a lightly regulated and generously subsidized insurance industry. Establishment Democrats haven’t merely gone post-hope—they’ve declared war on it.

_________

*Single-payer is just one way of organizing a public health insurance system. Under such a model, providers remain private and the government pays the bills. That is, only the insurance function is socialized. This is how it works in Canada. Under Britain’s National Health Service, everything is socialized: doctors are public employees and hospitals are government-owned. Sanders is proposing the former, even though the British system is cheaper to run than the Canadian, as the graph shows.

There were a couple of calls on Twitter for a transcript of what I said on last week’s radio show, following my interview with Benjamin Page. Page had said in the interview that he couldn’t find any foundations interested in funding research by him and his collaborators into the opinions of the top 1%. I’ve added a link to the Leah Gordon interview, which has a link to her book. I’ve expanded a bit on the original in this version.

It’s interesting that the foundations don’t want to support research into the opinions of the upper classes. Page, of course, is too careful a scholar to put it bluntly, but I’m not inhibited by those sorts of constraints. Foundations, almost without exception, exist to put a friendly face on plutocracy, and the last thing that plutocrats want is scrutiny of themselves. They’re interested in melioration but quite opposed to anything too structurally radical. Their role in shaping social science research is profound: recall my interview with Leah Gordon last June about how elite foundations shifted the emphasis in research on race relations away from structural issues towards individual psychology, “from power to prejudice,” as the title of her book put it. Questions interest them far more than answers.

Philanthropy doesn’t get anywhere near the critical attention it deserves, in large part because the kinds of intellectuals who could do that work are dependent on those philanthropies for funding. (I don’t blame the grantees—it’s hard to get by in this world.) I’m not dependent on their generosity, so I’m doing my best to fill in that gap.

Share this:

Like this:

Leave a Comment

Posted in radio commentaries, Uncategorized | Tags: foundations, philanthropy