Book Reviews by Seán Sheehan

Fiction

Dirt Road, James Kelman (Canongate)

You don’t have to be a Corbynista to know that the Establishment does not encourage radical politics of the genuinely socialist kind and that it will do whatever it can to belittle any group garnering mass support for daring to challenge the status quo. In the domain of cultural practice, mutatis mutandis, hugely important figures like Ken Loach and James Kelman are marginalized by the intelligentsia for the same underlying reason.

You don’t have to be a Corbynista to know that the Establishment does not encourage radical politics of the genuinely socialist kind and that it will do whatever it can to belittle any group garnering mass support for daring to challenge the status quo. In the domain of cultural practice, mutatis mutandis, hugely important figures like Ken Loach and James Kelman are marginalized by the intelligentsia for the same underlying reason.

The political order wants safe middle-of-the-road parties and it matters not a great deal which of the established parties steers the ship of state; the cultural order appears to be liberatory in its warm acceptance of the whole aesthetic gamut but it shies away from Ken Loach’s films and James Kelman’s novels, leaving it to non-British critics and commentators to praise their cinematic and literary achievements. Kelman know the score:

‘areas of human experience [I write about] should not appear in public; we don’t want to know. We know that people are in the street, that they have no money and are maybe begging, but we don’t want to see them in literature. They should be swept under the carpet.’

Lifting up the carpet and sweeping out what is underneath has been a trademark of Kelman’s writing – tastefully dismissed as ‘pugilism’ by bourgeois supremo critic James Wood – but Dirt Road cannot be so easily pigeon-holed. It is a story about grief, a terrible family loss that a father and his son have to cope with, but without the emotionalism that characterises humanist fiction on painful topic. It’s a road-trip novel but without the romance or consolation or violence you expect to find in books about journeys across the Deep South.

What makes it special is the language, the way we don’t express our feelings in neat sentences with carefully chosen adjectives and adverbs to nuance our refined sensibilities, the inarticulateness that is part of the expression of anguish and of hope. No living writer does this better than Kelman and Dirt Road quietly explores what it is like to struggle with the awful sense of loss that inhabits the body and mind when someone who was close dies.

My Brilliant Friend, Elena Ferrante (Europa Editions)

This is the first of the four Neapolitan novels by the mysterious Elena Ferrante – a tiny handful of people know who she is (assuming the author is a woman) and their lips are sealed – and introduces the friendship between the bookish and brilliant Elena and the fiery iconoclast Lila. The first book is set in post-World War Two Naples, where Elena and Lila are childhood buddies, and it’s a story of camaraderie and conflict.

This is the first of the four Neapolitan novels by the mysterious Elena Ferrante – a tiny handful of people know who she is (assuming the author is a woman) and their lips are sealed – and introduces the friendship between the bookish and brilliant Elena and the fiery iconoclast Lila. The first book is set in post-World War Two Naples, where Elena and Lila are childhood buddies, and it’s a story of camaraderie and conflict.

By the end of reading My Brilliant Friend you are likely to be hooked and proceed immediately to The Story of a New Name, then Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay and, finally, The Story of the Lost Child. The novels carry you along as Elena, the narrator, and Lila grow up into a world of politics, marriage and family but this is a million miles away from chick-lit.

It is difficult to pin down the way in which the reader, female or male, is drawn into the lives of these two women but I suspect it has something to do with all of us not just knowing a Lila and Elena but having or wanting to have a part of them in our own makeup.

His Bloody Project, Graeme Macrae Burnet (Contraband)

Walter Benjamin’s notion of ‘divine violence’, not readily comprehensible, becomes a lot clearer after reading His Bloody Project. The novel’s story is a lucid instance of what Benjamin was getting at when he talks of it as a means without an end:

Walter Benjamin’s notion of ‘divine violence’, not readily comprehensible, becomes a lot clearer after reading His Bloody Project. The novel’s story is a lucid instance of what Benjamin was getting at when he talks of it as a means without an end:

‘As regards man, he is impelled by anger, for example, to the most visible outbursts of a violence that is not related as a means to a preconceived end. It is not a means but a manifestation’ In its own situation, divine violence is ‘just, universally acceptable, and valid’ but not for other situations ‘even when they are similar in other respects.’ (‘Critique of Violence’ in Reflections).

Žižek in Against the Double Blackmail finds instances of divine violence in the Ferguson protests in 2014, the Baltimore riots of 2015 but for a visceral and affective experience of the truth behind the notion, the fictional situation in His Bloody Project brings it home.

It tells the story of a crofter and a triple murder in a Scottish village in the Highlands.

The Census-Taker, China Miéville (Macmillan)

The Russian formalists used to say, I read somewhere recently, that the function of art was to put you a knight’s-move away from reality; if so, Miéville wins hands down and his latest published piece of fiction, a novella, only confirms what has been known for a long time: he is supreme at tickling the imagination without descending into escapist fantasy.

The Russian formalists used to say, I read somewhere recently, that the function of art was to put you a knight’s-move away from reality; if so, Miéville wins hands down and his latest published piece of fiction, a novella, only confirms what has been known for a long time: he is supreme at tickling the imagination without descending into escapist fantasy.

The Census-Taker begins conventionally enough with a child running down a hillside to announce that his father has been killed by his mother but before you’ve turned the first page it’s clear that conventional narrative has gone out the window.

Similarly with the setting which mixes the familiar with the puzzling so that the reader is never quite sure if the story is unfolding in some dystopian future, in some metaphorical parallel universe or a sort-of Third World location in the twenty-first century – it’s best to assume it’s all of these.

Having read it once, you are obliged to start again and read it more carefully and let the language do its elusive work.

Non-Fiction

India, Steve McCurry (Phaidon)

India and the photographs in this book raise contradictory impulses so in this sense the country and Steve McCurry are made for each other. Writing about the images invites the most slavish kind of advertising copy so let’s preserve a shred of integrity and quote what others have said: ‘A celebration of the poetry of photography, of colour, form, chaos and human drama’ (Condé-Nast Traveller); ‘Incredible photographs that change the way we look at the world’ (The Sunday Times’). Such hyperbole justifies itself when you turn the pages of this new portfolio of 100 large-format images taken across the Indian subcontinent. The colours are scorchingly gorgeous, the light limpid or mysteriously dark, the mood often melancholy but also sociological and nearly always sympathetic to the subject matter. They can be astonishingly original, like the one of border guards riding camels through a desert armed with high-powered rifles but also predictably iconic of India (a steam engine passing in front of the Taj Mahal, a tailor carrying his sewing machine through monsoon floodwaters). Some of the images may be familiar from National Geographic but many more are published here for the first time and they will take your breath away.

India and the photographs in this book raise contradictory impulses so in this sense the country and Steve McCurry are made for each other. Writing about the images invites the most slavish kind of advertising copy so let’s preserve a shred of integrity and quote what others have said: ‘A celebration of the poetry of photography, of colour, form, chaos and human drama’ (Condé-Nast Traveller); ‘Incredible photographs that change the way we look at the world’ (The Sunday Times’). Such hyperbole justifies itself when you turn the pages of this new portfolio of 100 large-format images taken across the Indian subcontinent. The colours are scorchingly gorgeous, the light limpid or mysteriously dark, the mood often melancholy but also sociological and nearly always sympathetic to the subject matter. They can be astonishingly original, like the one of border guards riding camels through a desert armed with high-powered rifles but also predictably iconic of India (a steam engine passing in front of the Taj Mahal, a tailor carrying his sewing machine through monsoon floodwaters). Some of the images may be familiar from National Geographic but many more are published here for the first time and they will take your breath away.

The contradictory impulse comes from the suspicion not that Photoshopping might have taken place – when evidence of this has come to light in the past McCurry has blamed assistants – because how egregious this is surely depends on the degree of changes introduced to the final image. A little colour manipulation here and there should not be an excuse for righteous indignation and the adoption of the high purist ground. More serious is the charge that McCurry’s images of poverty are picturesque and that his gaze on the exotic Other is that of the tourist and the imperialist (à la Said’s Orientalism). It’s a hard call to make because India invites conflicting responses and McCurry does not shy away from photographing the most awful deprivation and the ostentatious extravagance that exists side by side. He also captures the sense of the spiritual that pervades everyday life and that can be doubting his intense engagement with the country. No one else has taken photographs like the ones in this book.

Revolutionary Lives: Constance and Casimir Markievicz, Lauren Arrington (Princeton University Press)

Books about revolutionary times in Ireland’s history are mostly about dead white Irish males so this biography makes a welcome change even though it is also about Constance Markievicz’s husband, a Polish count. The story begins in Lissadell in County Sligo where Constance grows up in an unorthodox but privileged milieu and moves on to her life in London and then to Paris where Maud Gonne was also living, though the two did not meet there. Constance returns to Ireland and participates in the Easter Rising, shooting a policeman it seems, and is saved from her sentence of death only because she is a woman.

Books about revolutionary times in Ireland’s history are mostly about dead white Irish males so this biography makes a welcome change even though it is also about Constance Markievicz’s husband, a Polish count. The story begins in Lissadell in County Sligo where Constance grows up in an unorthodox but privileged milieu and moves on to her life in London and then to Paris where Maud Gonne was also living, though the two did not meet there. Constance returns to Ireland and participates in the Easter Rising, shooting a policeman it seems, and is saved from her sentence of death only because she is a woman.

A chapter in the book, entitled ‘Conversion’, covers the way in which her anti-imperialism developed into socialism under the influence of Connolly. In the 1920s her politics and her sex saw her being ostracised by male voices of the three Os — O’Faolain, O’Flaherty and O’Casey—and her support for Bolshevism was not shared by her husband.

Revolutionary Lives tells the story of both their lives without being hagiographical and without succumbing to the caricatures pedalled by men about a woman with a gun.

The Lives of Robert Ryan, J.R. Jones (Wesleyan University Press)

The first great movie Robert Ryan appeared in was the film noir Crossfire (1947) and he went on to illuminate some superb Westerns — The Naked Spur (1953), Day of the Outlaw (1959) and The Wild Bunch (1969) – plus one-off specials like The Set-Up (1949), On Dangerous Ground (1952), Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) and Men in War (1956). The story of the man who helped make all these films so memorable is told with a commendable understanding that is usually missing in cliché-ridden and boringly factual books about movie stars.

The first great movie Robert Ryan appeared in was the film noir Crossfire (1947) and he went on to illuminate some superb Westerns — The Naked Spur (1953), Day of the Outlaw (1959) and The Wild Bunch (1969) – plus one-off specials like The Set-Up (1949), On Dangerous Ground (1952), Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) and Men in War (1956). The story of the man who helped make all these films so memorable is told with a commendable understanding that is usually missing in cliché-ridden and boringly factual books about movie stars.

Robert Ryan – his grandparents had immigrated from County Tipperary in 1852.– worked for the repellent Howard Hughes at RKO and being a good liberal at the height of whipped-up ‘reds under the beds’ paranoia he had little choice but to keep his head down. He was a keen supporter of the Democrats at a time when they were more like a party led by Bernie Sanders than by Hilary Clinton. When he reached his mid-forties he was denied the kind of romantic roles that Gary Cooper and Cary Grant managed to continue making into their fifties and when he did shine in a good film like Day of the Outlaw it bombed at the box office. He is probably best remembered today for his role in The Wild Bunch but seven years earlier he is equally remarkable in Billy Budd (1962) where the homoerotic undertones of his relationship with the beautifully angelic Terrence Stamp bear testimony to the director’s comment (Peter Ustinov) that Ryan was ‘a massive and wicked presence on the screen’.

Joyce’s Allmaziful Plurabilities: Polyvocal Explorations of Finnegans Wake, edited by Kimberley Devlin and Christine Smedley (University Press of Florida)

OK, the title of this collection of 17 essays by Joyce scholars is not exactly endearing but don’t let this put you off enjoying some sparkling insights into the greatest unread book in world literature. In one of the pieces, for example, Jim LeBlanc explores the uncanny concordance between Sartre’s Being and Nothingness and the second chapter of the Wake’s Book 1.Christine Smedley looks at the famine imagery in the seventh chapter and her essay is not as reductive as a criticism by Finn Fordham suggests it is in February’s issue of the James Joyce Broadsheet.

OK, the title of this collection of 17 essays by Joyce scholars is not exactly endearing but don’t let this put you off enjoying some sparkling insights into the greatest unread book in world literature. In one of the pieces, for example, Jim LeBlanc explores the uncanny concordance between Sartre’s Being and Nothingness and the second chapter of the Wake’s Book 1.Christine Smedley looks at the famine imagery in the seventh chapter and her essay is not as reductive as a criticism by Finn Fordham suggests it is in February’s issue of the James Joyce Broadsheet.

Enda Duffy, whose The Subaltern Ulysses remains an important contribution to Joyce studies, offers a convincing account of how one chapter of the Wake (11.3) is all about ‘the generation of courage’ for the working class and the unique experience of a good night out in a Dublin pub.

The Real People of Joyce’s Ulysses: A Biographical Guide, Vivien Igoe (University College Dublin Press)

Another valuable contribution to the Joyce industry comes from University College of Dublin (ucdpress,ie), the very institution attended by our churlish upstart in the early twentieth century. This is a book for Joyce aficionadas, especially close readers of Ulysses who want to know more about all those major and minor characters who populate the book.

Another valuable contribution to the Joyce industry comes from University College of Dublin (ucdpress,ie), the very institution attended by our churlish upstart in the early twentieth century. This is a book for Joyce aficionadas, especially close readers of Ulysses who want to know more about all those major and minor characters who populate the book.

Wherever possible, Vivien Igie has provided photographs of the real people and detailed information about where they lived, worked and intermingled, where they died and are buried. It is a unrivalled piece of detailed research and probably no one but Vivien Igoe could have brought it to fruition. Like Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels but in a very different way, The Real People of Joyce’s Ulysses collapses the distinction between fact and fiction.

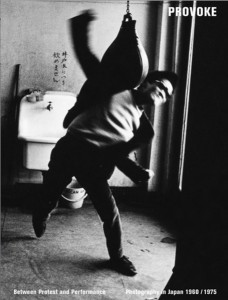

PROVOKE, edited by Diane Dufour, Matthew Witkovsky and Duncan Forbes (Stiedl)

Provoke was a Japanese photography magazine, launched by two photographers, a critic and a poet, that appeared for three issues, the first at the end of 1968 and two more the following year.

Provoke was a Japanese photography magazine, launched by two photographers, a critic and a poet, that appeared for three issues, the first at the end of 1968 and two more the following year.

This book from Stiedl has been published alongside the exhibition dedicated to Provoke that took place this year in a small number of European cities and Chicago. The magazine has now become a metonym for a short-lived era of protest in post-war Japan – this was 1968 remember – Provoke being bound up with the social and political protests of the time, a remnant of which is the continuing discontent with the massive American presence on Okinawa.

The magazine’s experimental aesthetic, a rejection of traditional journalistic forms, used visual images to incite thought and behaviour by turning away from supposedly ‘objective’ pictures of reality. Its trademark was blurred, out-of-focus grainy images and most of them are reproduced across the 680 pages of this definitive history of the magazine, plus interviews with the artists, essays and key texts translated into English for the first time.

South & West Coasts of Ireland: Sailing Directions, edited by Norman Kean (Irish Cruising Club)

OK, arriving at Cork Airport and seeing giant advertising displays for the Wild Atlantic Way is one thing but having its logo in your face not just at every junction but countless points between junctions…well that’s something else. It’s state propaganda of a particularly insidious kind, totalitarian in its insistence that the way to experience the west coast of Ireland is by sitting in a motor vehicle and following the signs like some dumbed-down tourist who doesn’t know how to experience somewhere new. The signs blight the countryside and the concept – wildness ffrom the comfort of your car — blights the mind. The only escape is to take to the hills before they too are signposted to death or – and this seems the best bet – leave the land and see the coastline from the water.

At least they can’t pollute the sea with signposts and logos and all the directions you need are contained within one book. South & West Coasts of Ireland: Sailing Directions is now in its 14th edition (2016) and while avid sailors of the west coast will be familiar with the publication it is likely to be new to occasional sailors or, like me, jaded landlubbers who are passengers in other people’s boats. This is a precious book and copies of it should be withheld from Failte Ireland and any land-based ‘community’ project designed to sucker visitors into despoiling the countryside by driving through it and stopping at designated viewing points to take half a dozen photos that no one will look at.

We Are All Cannibals, Claude Lévi-Strauss (Columbia University Press)

Once all the rage, Lévi-Strauss is currently out of fashion because he became too closely associated with structuralism and no career-conscious academic is going to wag that tail any more but this collection of his articles for an Italian newspaper shows how stimulating and insightful he can be on cultural topics. Binary oppositions are still there but only to illuminate the difficulties of judging other cultures, knotty questions that make it all the more astonishing that these essays were written for a newspaper. The flaccid intellectualism of The Irish Times makes a sad comparison.

The origins of Santa Claus and why he was hung from Dijon’s cathedral, a connection between mad cow disease and New Guinea cannibals showing how the concept of cannibalism has no objective status – ‘it exists only in the eyes of the societies that proscribe it’ – are just two of the topics that enliven this neat collection of thought-provoking essays.

The Extraordinary Beauty of Birds: Designs, Patterns and Details, Deborah Samuel (Prestel Publishing)

What you read in the title is what you see inside the pages of this book: extraordinary photographs of feathers, eggs, nests and skins of birds from around the world but collected together in the Royal Ontario Museum. The images are astonishing because without the book’s title and captions it would be hard to believe that some of them were not computer generated.

What you read in the title is what you see inside the pages of this book: extraordinary photographs of feathers, eggs, nests and skins of birds from around the world but collected together in the Royal Ontario Museum. The images are astonishing because without the book’s title and captions it would be hard to believe that some of them were not computer generated.

This is Nature imitating exquisite geometries and colours from the world of art and the result looks like some virtual reality created by digital technology until the box of text that accompanies each photograph is read. The text is meticulously empirical, making the image even more magical because the pattern and the colours are out there in the natural world.

.

Related Posts

Latest posts by Seán Sheehan (see all)

- New Books Worth Reading - September 19, 2016

- Spring Reading Selection - April 20, 2016

- Two Books Set in Ireland: Photography and Fiction - March 1, 2016

- Artist and Empire - February 24, 2016

- Photography & Fiction Books of 2015 - January 4, 2016