President Obama published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association today discussing the current state of his health care reform initiatives. Fortunately, the article is not behind a paywall. But JAMA nonetheless asserts their ownership and right to control the article’s use, as they do on all articles they publish, by attaching the following to the article’s PDF.

Unfortunately for JAMA, they have no right to do this. Section 105 of US Copyright law makes clear that works of the US government – and POTUS is a government employee last time I checked – are not eligible for copyright protection in the US (and JAMA is in the US).

17 U.S. Code § 105 – Subject matter of copyright: United States Government works

Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government, but the United States Government is not precluded from receiving and holding copyrights transferred to it by assignment, bequest, or otherwise.

It is completely inexcusable for journals to assert a right they are aware they do not have, thereby undoubtedly leading to people failing to make use of the article in ways that they are clearly legally eligible to do, such as redistributing and reusing the content, as I am doing here.

Special Communication | July 11, 2016

United States Health Care Reform: Progress to Date and Next Steps

Barack Obama, JD1

1President of the United States, Washington, DC

Importance The Affordable Care Act is the most important health care legislation enacted in the United States since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. The law implemented comprehensive reforms designed to improve the accessibility, affordability, and quality of health care.

Objectives To review the factors influencing the decision to pursue health reform, summarize evidence on the effects of the law to date, recommend actions that could improve the health care system, and identify general lessons for public policy from the Affordable Care Act.

Evidence Analysis of publicly available data, data obtained from government agencies, and published research findings. The period examined extends from 1963 to early 2016.

Findings The Affordable Care Act has made significant progress toward solving long-standing challenges facing the US health care system related to access, affordability, and quality of care. Since the Affordable Care Act became law, the uninsured rate has declined by 43%, from 16.0% in 2010 to 9.1% in 2015, primarily because of the law’s reforms. Research has documented accompanying improvements in access to care (for example, an estimated reduction in the share of nonelderly adults unable to afford care of 5.5 percentage points), financial security (for example, an estimated reduction in debts sent to collection of $600-$1000 per person gaining Medicaid coverage), and health (for example, an estimated reduction in the share of nonelderly adults reporting fair or poor health of 3.4 percentage points). The law has also begun the process of transforming health care payment systems, with an estimated 30% of traditional Medicare payments now flowing through alternative payment models like bundled payments or accountable care organizations. These and related reforms have contributed to a sustained period of slow growth in per-enrollee health care spending and improvements in health care quality. Despite this progress, major opportunities to improve the health care system remain.

Conclusions and Relevance Policy makers should build on progress made by the Affordable Care Act by continuing to implement the Health Insurance Marketplaces and delivery system reform, increasing federal financial assistance for Marketplace enrollees, introducing a public plan option in areas lacking individual market competition, and taking actions to reduce prescription drug costs. Although partisanship and special interest opposition remain, experience with the Affordable Care Act demonstrates that positive change is achievable on some of the nation’s most complex challenges.

Health care costs affect the economy, the federal budget, and virtually every American family’s financial well-being. Health insurance enables children to excel at school, adults to work more productively, and Americans of all ages to live longer, healthier lives. When I took office, health care costs had risen rapidly for decades, and tens of millions of Americans were uninsured. Regardless of the political difficulties, I concluded comprehensive reform was necessary.

The result of that effort, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), has made substantial progress in addressing these challenges. Americans can now count on access to health coverage throughout their lives, and the federal government has an array of tools to bring the rise of health care costs under control. However, the work toward a high-quality, affordable, accessible health care system is not over.

In this Special Communication, I assess the progress the ACA has made toward improving the US health care system and discuss how policy makers can build on that progress in the years ahead. I close with reflections on what my administration’s experience with the ACA can teach about the potential for positive change in health policy in particular and public policy generally.

In my first days in office, I confronted an array of immediate challenges associated with the Great Recession. I also had to deal with one of the nation’s most intractable and long-standing problems, a health care system that fell far short of its potential. In 2008, the United States devoted 16% of the economy to health care, an increase of almost one-quarter since 1998 (when 13% of the economy was spent on health care), yet much of that spending did not translate into better outcomes for patients.1– 4 The health care system also fell short on quality of care, too often failing to keep patients safe, waiting to treat patients when they were sick rather than focusing on keeping them healthy, and delivering fragmented, poorly coordinated care.5,6

Moreover, the US system left more than 1 in 7 Americans without health insurance coverage in 2008.7 Despite successful efforts in the 1980s and 1990s to expand coverage for specific populations, like children, the United States had not seen a large, sustained reduction in the uninsured rate since Medicare and Medicaid began (Figure 18– 10). The United States’ high uninsured rate had negative consequences for uninsured Americans, who experienced greater financial insecurity, barriers to care, and odds of poor health and preventable death; for the health care system, which was burdened with billions of dollars in uncompensated care; and for the US economy, which suffered, for example, because workers were concerned about joining the ranks of the uninsured if they sought additional education or started a business.11– 16 Beyond these statistics were the countless, heartbreaking stories of Americans who struggled to access care because of a broken health insurance system. These included people like Natoma Canfield, who had overcome cancer once but had to discontinue her coverage due to rapidly escalating premiums and found herself facing a new cancer diagnosis uninsured.17

In 2009, during my first month in office, I extended the Children’s Health Insurance Program and soon thereafter signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which included temporary support to sustain Medicaid coverage as well as investments in health information technology, prevention, and health research to improve the system in the long run. In the summer of 2009, I signed the Tobacco Control Act, which has contributed to a rapid decline in the rate of smoking among teens, from 19.5% in 2009 to 10.8% in 2015, with substantial declines among adults as well.7,18

Beyond these initial actions, I decided to prioritize comprehensive health reform not only because of the gravity of these challenges but also because of the possibility for progress. Massachusetts had recently implemented bipartisan legislation to expand health insurance coverage to all its residents. Leaders in Congress had recognized that expanding coverage, reducing the level and growth of health care costs, and improving quality was an urgent national priority. At the same time, a broad array of health care organizations and professionals, business leaders, consumer groups, and others agreed that the time had come to press ahead with reform.19 Those elements contributed to my decision, along with my deeply held belief that health care is not a privilege for a few, but a right for all. After a long debate with well-documented twists and turns, I signed the ACA on March 23, 2010.

The years following the ACA’s passage included intense implementation efforts, changes in direction because of actions in Congress and the courts, and new opportunities such as the bipartisan passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) in 2015. Rather than detail every development in the intervening years, I provide an overall assessment of how the health care system has changed between the ACA’s passage and today.

The evidence underlying this assessment was obtained from several sources. To assess trends in insurance coverage, this analysis relies on publicly available government and private survey data, as well as previously published analyses of survey and administrative data. To assess trends in health care costs and quality, this analysis relies on publicly available government estimates and projections of health care spending; publicly available government and private survey data; data on hospital readmission rates provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; and previously published analyses of survey, administrative, and clinical data. The dates of the data used in this assessment range from 1963 to early 2016.

The ACA has succeeded in sharply increasing insurance coverage. Since the ACA became law, the uninsured rate has declined by 43%, from 16.0% in 2010 to 9.1% in 2015,7 with most of that decline occurring after the law’s main coverage provisions took effect in 2014 (Figure 18– 10). The number of uninsured individuals in the United States has declined from 49 million in 2010 to 29 million in 2015. This is by far the largest decline in the uninsured rate since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid 5 decades ago. Recent analyses have concluded these gains are primarily because of the ACA, rather than other factors such as the ongoing economic recovery.20,21 Adjusting for economic and demographic changes and other underlying trends, the Department of Health and Human Services estimated that 20 million more people had health insurance in early 2016 because of the law.22

Each of the law’s major coverage provisions—comprehensive reforms in the health insurance market combined with financial assistance for low- and moderate-income individuals to purchase coverage, generous federal support for states that expand their Medicaid programs to cover more low-income adults, and improvements in existing insurance coverage—has contributed to these gains. States that decided to expand their Medicaid programs saw larger reductions in their uninsured rates from 2013 to 2015, especially when those states had large uninsured populations to start with (Figure 223). However, even states that have not adopted Medicaid expansion have seen substantial reductions in their uninsured rates, indicating that the ACA’s other reforms are increasing insurance coverage. The law’s provision allowing young adults to stay on a parent’s plan until age 26 years has also played a contributing role, covering an estimated 2.3 million people after it took effect in late 2010.22

Early evidence indicates that expanded coverage is improving access to treatment, financial security, and health for the newly insured. Following the expansion through early 2015, nonelderly adults experienced substantial improvements in the share of individuals who have a personal physician (increase of 3.5 percentage points) and easy access to medicine (increase of 2.4 percentage points) and substantial decreases in the share who are unable to afford care (decrease of 5.5 percentage points) and reporting fair or poor health (decrease of 3.4 percentage points) relative to the pre-ACA trend.24 Similarly, research has found that Medicaid expansion improves the financial security of the newly insured (for example, by reducing the amount of debt sent to a collection agency by an estimated $600-$1000 per person gaining Medicaid coverage).26,27 Greater insurance coverage appears to have been achieved without negative effects on the labor market, despite widespread predictions that the law would be a “job killer.” Private-sector employment has increased in every month since the ACA became law, and rigorous comparisons of Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states show no negative effects on employment in expansion states.28– 30

The law has also greatly improved health insurance coverage for people who already had it. Coverage offered on the individual market or to small businesses must now include a core set of health care services, including maternity care and treatment for mental health and substance use disorders, services that were sometimes not covered at all previously.31 Most private insurance plans must now cover recommended preventive services without cost-sharing, an important step in light of evidence demonstrating that many preventive services were underused.5,6 This includes women’s preventive services, which has guaranteed an estimated 55.6 million women coverage of services such as contraceptive coverage and screening and counseling for domestic and interpersonal violence.32 In addition, families now have far better protection against catastrophic costs related to health care. Lifetime limits on coverage are now illegal and annual limits typically are as well. Instead, most plans must cap enrollees’ annual out-of-pocket spending, a provision that has helped substantially reduce the share of people with employer-provided coverage lacking real protection against catastrophic costs (Figure 333). The law is also phasing out the Medicare Part D coverage gap. Since 2010, more than 10 million Medicare beneficiaries have saved more than $20 billion as a result.34

Before the ACA, the health care system was dominated by “fee-for-service” payment systems, which often penalized health care organizations and health care professionals who find ways to deliver care more efficiently, while failing to reward those who improve the quality of care. The ACA has changed the health care payment system in several important ways. The law modified rates paid to many that provide Medicare services and Medicare Advantage plans to better align them with the actual costs of providing care. Research on how past changes in Medicare payment rates have affected private payment rates implies that these changes in Medicare payment policy are helping decrease prices in the private sector as well.35,36 The ACA also included numerous policies to detect and prevent health care fraud, including increased scrutiny prior to enrollment in Medicare and Medicaid for health care entities that pose a high risk of fraud, stronger penalties for crimes involving losses in excess of $1 million, and additional funding for antifraud efforts. The ACA has also widely deployed “value-based payment” systems in Medicare that tie fee-for-service payments to the quality and efficiency of the care delivered by health care organizations and health care professionals. In parallel with these efforts, my administration has worked to foster a more competitive market by increasing transparency around the prices charged and the quality of care delivered.

Most importantly over the long run, the ACA is moving the health care system toward “alternative payment models” that hold health care entities accountable for outcomes. These models include bundled payment models that make a single payment for all of the services provided during a clinical episode and population-based models like accountable care organizations (ACOs) that base payment on the results health care organizations and health care professionals achieve for all of their patients’ care. The law created the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test alternative payment models and bring them to scale if they are successful, as well as a permanent ACO program in Medicare. Today, an estimated 30% of traditional Medicare payments flow through alternative payment models that broaden the focus of payment beyond individual services or a particular entity, up from essentially none in 2010.37 These models are also spreading rapidly in the private sector, and their spread will likely be accelerated by the physician payment reforms in MACRA.38,39

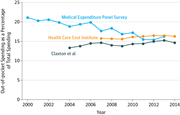

Trends in health care costs and quality under the ACA have been promising (Figure 41,40). From 2010 through 2014, mean annual growth in real per-enrollee Medicare spending has actually been negative, down from a mean of 4.7% per year from 2000 through 2005 and 2.4% per year from 2006 to 2010 (growth from 2005 to 2006 is omitted to avoid including the rapid growth associated with the creation of Medicare Part D).1,40 Similarly, mean real per-enrollee growth in private insurance spending has been 1.1% per year since 2010, compared with a mean of 6.5% from 2000 through 2005 and 3.4% from 2005 to 2010.1,40

As a result, health care spending is likely to be far lower than expected. For example, relative to the projections the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued just before I took office, CBO now projects Medicare to spend 20%, or about $160 billion, less in 2019 alone.41,42 The implications for families’ budgets of slower growth in premiums have been equally striking. Had premiums increased since 2010 at the same mean rate as the preceding decade, the mean family premium for employer-based coverage would have been almost $2600 higher in 2015.33 Employees receive much of those savings through lower premium costs, and economists generally agree that those employees will receive the remainder as higher wages in the long run.43 Furthermore, while deductibles have increased in recent years, they have increased no faster than in the years preceding 2010.44 Multiple sources also indicate that the overall share of health care costs that enrollees in employer coverage pay out of pocket has been close to flat since 2010 (Figure 545– 48), most likely because the continued increase in deductibles has been canceled out by a decline in co-payments.

At the same time, the United States has seen important improvements in the quality of care. The rate of hospital-acquired conditions (such as adverse drug events, infections, and pressure ulcers) has declined by 17%, from 145 per 1000 discharges in 2010 to 121 per 1000 discharges in 2014.49 Using prior research on the relationship between hospital-acquired conditions and mortality, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has estimated that this decline in the rate of hospital-acquired conditions has prevented a cumulative 87 000 deaths over 4 years.49 The rate at which Medicare patients are readmitted to the hospital within 30 days after discharge has also decreased sharply, from a mean of 19.1% during 2010 to a mean of 17.8% during 2015 (Figure 6; written communication; March 2016; Office of Enterprise Data and Analytics, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). The Department of Health and Human Services has estimated that lower hospital readmission rates resulted in 565 000 fewer total readmissions from April 2010 through May 2015.50,51

While the Great Recession and other factors played a role in recent trends, the Council of Economic Advisers has found evidence that the reforms introduced by the ACA helped both slow health care cost growth and drive improvements in the quality of care.44,52 The contribution of the ACA’s reforms is likely to increase in the years ahead as its tools are used more fully and as the models already deployed under the ACA continue to mature.

I am proud of the policy changes in the ACA and the progress that has been made toward a more affordable, high-quality, and accessible health care system. Despite this progress, too many Americans still strain to pay for their physician visits and prescriptions, cover their deductibles, or pay their monthly insurance bills; struggle to navigate a complex, sometimes bewildering system; and remain uninsured. More work to reform the health care system is necessary, with some suggestions offered below.

First, many of the reforms introduced in recent years are still some years from reaching their maximum effect. With respect to the law’s coverage provisions, these early years’ experience demonstrate that the Health Insurance Marketplace is a viable source of coverage for millions of Americans and will be for decades to come. However, both insurers and policy makers are still learning about the dynamics of an insurance market that includes all people regardless of any preexisting conditions, and further adjustments and recalibrations will likely be needed, as can be seen in some insurers’ proposed Marketplace premiums for 2017. In addition, a critical piece of unfinished business is in Medicaid. As of July 1, 2016, 19 states have yet to expand their Medicaid programs. I hope that all 50 states take this option and expand coverage for their citizens in the coming years, as they did in the years following the creation of Medicaid and CHIP.

With respect to delivery system reform, the reorientation of the US health care payment systems toward quality and accountability has made significant strides forward, but it will take continued hard work to achieve my administration’s goal of having at least half of traditional Medicare payments flowing through alternative payment models by the end of 2018. Tools created by the ACA—including CMMI and the law’s ACO program—and the new tools provided by MACRA will play central roles in this important work. In parallel, I expect continued bipartisan support for identifying the root causes and cures for diseases through the Precision Medicine and BRAIN initiatives and the Cancer Moonshot, which are likely to have profound benefits for the 21st-century US health care system and health outcomes.

Second, while the ACA has greatly improved the affordability of health insurance coverage, surveys indicate that many of the remaining uninsured individuals want coverage but still report being unable to afford it.53,54 Some of these individuals may be unaware of the financial assistance available under current law, whereas others would benefit from congressional action to increase financial assistance to purchase coverage, which would also help middle-class families who have coverage but still struggle with premiums. The steady-state cost of the ACA’s coverage provisions is currently projected to be 28% below CBO’s original projections, due in significant part to lower-than-expected Marketplace premiums, so increased financial assistance could make coverage even more affordable while still keeping federal costs below initial estimates.55,56

Third, more can and should be done to enhance competition in the Marketplaces. For most Americans in most places, the Marketplaces are working. The ACA supports competition and has encouraged the entry of hospital-based plans, Medicaid managed care plans, and other plans into new areas. As a result, the majority of the country has benefited from competition in the Marketplaces, with 88% of enrollees living in counties with at least 3 issuers in 2016, which helps keep costs in these areas low.57,58 However, the remaining 12% of enrollees live in areas with only 1 or 2 issuers. Some parts of the country have struggled with limited insurance market competition for many years, which is one reason that, in the original debate over health reform, Congress considered and I supported including a Medicare-like public plan. Public programs like Medicare often deliver care more cost-effectively by curtailing administrative overhead and securing better prices from providers.59,60 The public plan did not make it into the final legislation. Now, based on experience with the ACA, I think Congress should revisit a public plan to compete alongside private insurers in areas of the country where competition is limited. Adding a public plan in such areas would strengthen the Marketplace approach, giving consumers more affordable options while also creating savings for the federal government.61

Fourth, although the ACA included policies to help address prescription drug costs, like more substantial Medicaid rebates and the creation of a pathway for approval of biosimilar drugs, those costs remain a concern for Americans, employers, and taxpayers alike—particularly in light of the 12% increase in prescription drug spending that occurred in 2014.1 In addition to administrative actions like testing new ways to pay for drugs, legislative action is needed.62 Congress should act on proposals like those included in my fiscal year 2017 budget to increase transparency around manufacturers’ actual production and development costs, to increase the rebates manufacturers are required to pay for drugs prescribed to certain Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, and to give the federal government the authority to negotiate prices for certain high-priced drugs.63

There is another important role for Congress: it should avoid moving backward on health reform. While I have always been interested in improving the law—and signed 19 bills that do just that—my administration has spent considerable time in the last several years opposing more than 60 attempts to repeal parts or all of the ACA, time that could have been better spent working to improve our health care system and economy. In some instances, the repeal efforts have been bipartisan, including the effort to roll back the excise tax on high-cost employer-provided plans. Although this provision can be improved, such as through the reforms I proposed in my budget, the tax creates strong incentives for the least-efficient private-sector health plans to engage in delivery system reform efforts, with major benefits for the economy and the budget. It should be preserved.64 In addition, Congress should not advance legislation that undermines the Independent Payment Advisory Board, which will provide a valuable backstop if rapid cost growth returns to Medicare.

While historians will draw their own conclusions about the broader implications of the ACA, I have my own. These lessons learned are not just for posterity: I have put them into practice in both health care policy and other areas of public policy throughout my presidency.

The first lesson is that any change is difficult, but it is especially difficult in the face of hyperpartisanship. Republicans reversed course and rejected their own ideas once they appeared in the text of a bill that I supported. For example, they supported a fully funded risk-corridor program and a public plan fallback in the Medicare drug benefit in 2003 but opposed them in the ACA. They supported the individual mandate in Massachusetts in 2006 but opposed it in the ACA. They supported the employer mandate in California in 2007 but opposed it in the ACA—and then opposed the administration’s decision to delay it. Moreover, through inadequate funding, opposition to routine technical corrections, excessive oversight, and relentless litigation, Republicans undermined ACA implementation efforts. We could have covered more ground more quickly with cooperation rather than obstruction. It is not obvious that this strategy has paid political dividends for Republicans, but it has clearly come at a cost for the country, most notably for the estimated 4 million Americans left uninsured because they live in GOP-led states that have yet to expand Medicaid.65

The second lesson is that special interests pose a continued obstacle to change. We worked successfully with some health care organizations and groups, such as major hospital associations, to redirect excessive Medicare payments to federal subsidies for the uninsured. Yet others, like the pharmaceutical industry, oppose any change to drug pricing, no matter how justifiable and modest, because they believe it threatens their profits.66 We need to continue to tackle special interest dollars in politics. But we also need to reinforce the sense of mission in health care that brought us an affordable polio vaccine and widely available penicillin.

The third lesson is the importance of pragmatism in both legislation and implementation. Simpler approaches to addressing our health care problems exist at both ends of the political spectrum: the single-payer model vs government vouchers for all. Yet the nation typically reaches its greatest heights when we find common ground between the public and private good and adjust along the way. That was my approach with the ACA. We engaged with Congress to identify the combination of proven health reform ideas that could pass and have continued to adapt them since. This includes abandoning parts that do not work, like the voluntary long-term care program included in the law. It also means shutting down and restarting a process when it fails. When HealthCare.gov did not work on day 1, we brought in reinforcements, were brutally honest in assessing problems, and worked relentlessly to get it operating. Both the process and the website were successful, and we created a playbook we are applying to technology projects across the government.

While the lessons enumerated above may seem daunting, the ACA experience nevertheless makes me optimistic about this country’s capacity to make meaningful progress on even the biggest public policy challenges. Many moments serve as reminders that a broken status quo is not the nation’s destiny. I often think of a letter I received from Brent Brown of Wisconsin. He did not vote for me and he opposed “ObamaCare,” but Brent changed his mind when he became ill, needed care, and got it thanks to the law.67 Or take Governor John Kasich’s explanation for expanding Medicaid: “For those that live in the shadows of life, those who are the least among us, I will not accept the fact that the most vulnerable in our state should be ignored. We can help them.”68 Or look at the actions of countless health care providers who have made our health system more coordinated, quality-oriented, and patient-centered. I will repeat what I said 4 years ago when the Supreme Court upheld the ACA: I am as confident as ever that looking back 20 years from now, the nation will be better off because of having the courage to pass this law and persevere. As this progress with health care reform in the United States demonstrates, faith in responsibility, belief in opportunity, and ability to unite around common values are what makes this nation great.

Corresponding Author: Barack Obama, JD, The White House, 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW, Washington, DC 20500 (press@who.eop.gov).

Published Online: July 11, 2016. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.9797.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The author has completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The author’s public financial disclosure report for calendar year 2015 may be viewed at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/oge_278_cy_2015_obama_051616.pdf.

Additional Contributions: I thank Matthew Fiedler, PhD, and Jeanne Lambrew, PhD, who assisted with planning, writing, and data analysis. I also thank Kristie Canegallo, MA; Katie Hill, BA; Cody Keenan, MPP; Jesse Lee, BA; and Shailagh Murray, MS, who assisted with editing the manuscript. All of the individuals who assisted with the preparation of the manuscript are employed by the Executive Office of the President.

Anderson GF, Frogner BK. Health spending in OECD countries: obtaining value per dollar.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(6):1718-1727.

PubMed | Link to Article

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending: part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care.

Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273-287.

PubMed | Link to Article

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending: part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care.

Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):288-298.

PubMed | Link to Article

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States.

N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635-2645.

PubMed | Link to Article

Cohen RA, Makuc DM, Bernstein AB, Bilheimer LT, Powell-Griner E. Health insurance coverage trends, 1959-2007: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics.

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr017.pdf. Published July 1, 2009. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al; Oregon Health Study Group. The Oregon experiment: effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes.

N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713-1722.

PubMed | Link to Article

Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions.

N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1025-1034.

PubMed | Link to Article

Sommers BD, Long SK, Baicker K. Changes in mortality after Massachusetts health care reform: a quasi-experimental study.

Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(9):585-593.

PubMed | Link to Article

Hadley J, Holahan J, Coughlin T, Miller D. Covering the uninsured in 2008: current costs, sources of payment, and incremental costs.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(5):w399-w415.

PubMed | Link to Article

Fairlie RW, Kapur K, Gates S. Is employer-based health insurance a barrier to entrepreneurship?

J Health Econ. 2011;30(1):146-162.

PubMed | Link to Article

Dillender M. Do more health insurance options lead to higher wages? evidence from states extending dependent coverage.

J Health Econ. 2014;36:84-97.

PubMed | Link to Article

Oberlander J. Long time coming: why health reform finally passed.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(6):1112-1116.

PubMed | Link to Article

Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowtize A, Zapata D. Impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states [NBER working paper No. 22182]. National Bureau of Economic Research.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w22182. Published April 2016. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Blumberg LJ, Garrett B, Holahan J. Estimating the counterfactual: how many uninsured adults would there be today without the ACA?

Inquiry. 2016;53(3):1-13.

PubMed

Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, Musco T. Changes in self-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act.

JAMA. 2015;314(4):366-374.

PubMed | Link to Article

Shartzer A, Long SK, Anderson N. Access to care and affordability have improved following Affordable Care Act implementation; problems remain.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):161-168.

PubMed | Link to Article

Hu L, Kaestner R, Mazumder B, Miller S, Wong A. The effect of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions on financial well-being [NBER working paper No. 22170]. National Bureau of Economic Research.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w22170. Published April 2016. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Kaestner R, Garrett B, Gangopadhyaya A, Fleming C. Effects of the ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and labor supply [NBER working paper No. 21836]. National Bureau of Economic Research.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w21836. Published December 2015. Accessed June 14, 2016.

White C. Contrary to cost-shift theory, lower Medicare hospital payment rates for inpatient care lead to lower private payment rates.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(5):935-943.

PubMed | Link to Article

Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds.2015 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. Washington, DC: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2015.

Congressional Budget Office. Private Health Insurance Premiums and Federal Policy. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2016.

Herrera CN, Gaynor M, Newman D, Town RJ, Parente ST. Trends underlying employer-sponsored health insurance growth for Americans younger than age sixty-five.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1715-1722.

PubMed | Link to Article

Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program.

N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551.

PubMed | Link to Article

Council of Economic Advisers. 2014 Economic Report of the President. Washington, DC: Council of Economic Advisers; 2014.

Congressional Budget Office. HR 4872, Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Final Health Care Legislation).

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/21351. Published March 20, 2010. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Congressional Budget Office. Federal subsidies for health insurance coverage for people under age 65: 2016 to 2026.

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51385. Published March 24, 2016. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Wallace J, Song Z. Traditional Medicare versus private insurance: how spending, volume, and price change at age sixty-five.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):864-872.

PubMed | Link to Article

Office of Management and Budget. Budget of the United States Government: Fiscal Year 2017. Washington, DC: Office of Management and Budget; 2016.

Furman J, Fiedler M. The Cadillac tax: a crucial tool for delivery-system reform.

N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1008-1009.

PubMed | Link to Article

Kasich JR. 2013 State of the State Address. Lima: Ohio State Legislature; 2013.

I'm a biologist at UC Berkeley and an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. I work primarily on flies, and my research encompases evolution, development, genetics, genomics, chemical ecology and behavior. I am a strong proponent of open science, and a co-founder of the

I'm a biologist at UC Berkeley and an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. I work primarily on flies, and my research encompases evolution, development, genetics, genomics, chemical ecology and behavior. I am a strong proponent of open science, and a co-founder of the