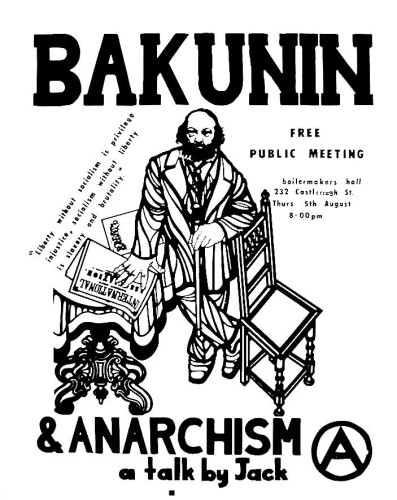

I just learned that Jelesko ‘Jack’ Grancharoff (July 5, 1925–May 15, 2016) has died. ‘Jack the Anarchist’ was a working class intellectual, published a long-running zine Red and Black, and was an ubiquitous presence at anarchist events, from the 1960s through to early this century. Jack looked like Karl Marx, but embodied the spirit of Mikhail Bakunin. I remember writing to him some time in the early 1990s to obtain copies of his zine, but unfortunately I only saw him speak on a handful of occasions, the last time at a recent anarchist conference. Below are several short writings on Jack, his life, and political work. The first two are extracts from Anne Coombs’ book on the Sydney Push, Sex and Anarchy (Viking, 1996: pp.101-103; 151-152), the third prompted by a talk Jack gave at Jura in 2013, and the last an extract from a June 29, 2006 letter to The Sydney Morning Herald by Dave Clark (1946–2008: Economist, Larrikin, ‘Critical Drinker’ and Friend). You can read much more about Jack on Takver’s site, including a reference to his ASIO file, which contains ‘a nice letter from Jack to an ASIO agent who has subscribed to Red and Black and wants to attend anarchist meetings’ LOL. I hope and expect that others who knew Jack will make further reflections on his life and times available in future. If I find the time, I may scan and upload some of the articles he wrote for Red and Black.

Rest in Power Comrade Jack!

1)

Jack the Anarchist was another who never strictly followed the Libertarian line but who nonetheless found he was more comfortable among them than anywhere else. Jack Grancharoff was a political refugee from Bulgaria when he arrived in Australia in 1950. He, too, discovered the Push in 1956.

‘I was searching for some group that might be interested in social theory. I met some communists in the Domain, some Trotskyists, and had some arguments with them. Somebody told me that there were people like me drinking in a pub in Phillip Street, the Assembly.’

Jack found the Push to his liking. He had become interested in anarchism in Europe, and since arriving in Australia had been looking for sympathetic minds. This search had taken him up and down the country. Anarchism was, and still is, his mission in life and he has worked in a variety of unskilled jobs to support it, from Melbourne to northern Queensland.

In Sydney, he worked on the trams. He became a familiar figure to many: in his blue tram conductor’s uniform, a stocky figure with long hair and flowing beard; in Push pubs; at student conferences. One Push member remembers seeing Jack in the Domain, not long after he had arrived in Sydney, standing on a pickle barrel haranguing his audience with an accent so thick it was hard to understand him.

Jack and the anarchists, a couple of them fellow Bulgarians, became known within the Push as ‘the Bulgarian anarchists’. Darcy [Waters: 1928–1997] recalls an early meeting with them.

‘They came to the uni one evening for a meeting — it must have been the late 1950s. They frightened the fucking daylights out of me. They were proposing dangerous bloody things.

‘I told them that I had a lot of sympathy for their position but I wasn’t going to go out there and die for freedom. They got quite upset. We went off and had coffee with them. One was a young girl, in her mid-twenties. She said at one stage that she was prepared to die for freedom, then and there. I found this attitude pretty bloody frightening — she meant it.’

Jack’s political position put him mid-way between the Libertarians and the European-style anarchists who called themselves the Anarchist Group. He liked the individualism of the Libertarians, a kind of personal anarchism, as opposed to the more organised anarcho-communists.

Jack says, ‘Some anarchists thought the Libertarians were not anarchists but they were quite wrong because at the time the Libertarians were the only ones expressing social theory quite critically and anarchistically.’ They were attractive to a lot of people, particularly ex-communists. ‘They argued the issues, like why communism failed.’

When he speaks of these groups, he often speaks in the present tense, unlike almost everyone else. To him, this life is not over. He continues to live much as he did thirty or forty years ago. But he is not an anachronism. Indeed, his critique seems sharper now than ever.

‘The only way to a more anarchistic view in Australia is via libertarianism. They had a social critique, but they didn’t believe they were going to change society.’

Jack broke with the Anarchist Group because of his friendship with the Libertarians. He remained slightly on the outer of both groups. The Libertarians liked him and thought him a good bloke but he does not seem to have been regarded as a true intellectual, even though he certainly was, and is. Rather, he was seen as a cheery fellow who was good company. Of course, he did not have a university education. And he was not a competitor in the sexual stakes.

Nor did Jack wish to be a true Libertarian. He respected them but he disagreed with them on a number of things, including their sexual theory: what he calls ‘polygamy’.

‘Now the thing to me is: why the polygamy? Why did they have to be polygamous? Promiscuity became a sort of doctrine. In a way, there was not sufficient criticism of sexuality, and not sufficient criticism of hierarchy either.

‘Let’s face it, they probably rationalised their whole behaviour. Being promiscuous, you were being progressive, being promiscuous, you were a critical thinker, being promiscuous, you had a radical philosophy. If you were not, then you were not radical. Their radicalism was a limited radicalism.

‘What was wrong with the Libertarians was that their radical critique did not go far enough. I think they were on the right road. They said they were not proselytising but it was still the kind of critique that was very important.

‘Their radical criticism should have continued. Instead, they were stuck to theories like [Wilhelm] Reich on sexuality because these were pleasing to young people who felt sexually repressed. They didn’t go far enough. They hint at hierarchy, at oligarchy, but then they accept it, nothing you can do about it — the only thing you can do is to live your life as freely as possible. But to me the liberty that is limited is not liberty. They don’t attack the hierarchy sufficiently, and also polygamy in no sense implies that there is no hierarchy in it.’

2)

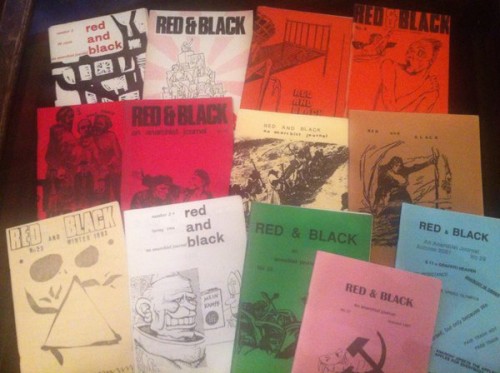

Back in January 1960 the Libertarian had announced that a new anarchist journal was about to be launched. The first issue was planned for April/May of that year and was to be put out by ‘Sydney anarchists, members of the Libertarian Society, and others’. It would be called Red and Black. The name was appropriate for a number of reasons, not least because Stendahl’s novel The Red and the Black was being passed around Libertarian circles at the time. This would have been of some significance to the nascent novelist Ian Bedford [1938–2015], who was one of those involved in the new project.

But Red and Black took longer to get off the ground than planned. Nothing happened in 1960 and the idea was shelved. It was talked about in 1963 but still nothing happened. Then, in 1965, Jack the anarchist took it on. The first issue was printed by Nestor Grivas, as was the second issue the following year.

Jack had given a few papers at Libertarian meetings in the Philosophy Room — one on the Catholic Church, in 1960, and another in 1964 on the German/American anarchist Johann Most, an intimate of Emma Goldman. But it was downtown that Jack had most impact. He was a downtown intellectual par excellence. He combined a keen mind and a liking for beer.

None of that has changed. Thirty years later, Red and Black is still published, intermittently. As it always has, it continues to publish articles by academics, ‘street’ anarchists and European and American radicals. Sometimes it publishes pieces by foreign writers who have not been able to get their views accepted elsewhere. Jack, who is fluent in several languages, digs out articles from obscure foreign journals that few people in Australia are likely to have heard of. When he has sufficient material and sufficient funds he brings out an edition of Red and Black. Each issue has a circulation of around 400. Its contents reflect changing times, while maintaining a commitment to anarchism.

The early issues were not so different from the Libertarian-inspired journals. With the exception of Jack, most of the contributors were academics. But it was Jack’s pieces that gave the magazine relevance and currency. In 1966, for example, he wrote on ‘Vietnam’, while the academics were still talking about ‘The IWW in America’ and ‘Lenin and Workers’ Control’.

Jack’s respect and liking for individual Libertarians was tinged with annoyance at their apathy and what he saw as the sense of powerlessness that lay behind their futilitarianism.

‘If they really believed in futilitarianism, then giving papers didn’t make sense’, he says. ‘Giving papers is, to me, action’.

He thinks the Libertarians were afraid of activism, ‘because activism requires a different kind of theoretical approach. They were afraid of activism because activism brings up ideologies and that’s where they would give up. They wanted to maintain their purity. But their purity is the purity of a people who are fading away from not taking account of the reality that is surrounding them.’

3)

Jura Books in Sydney recently hosted [May 2013] ‘Anarchism in Bulgaria: As I See It’ by the 88-year-old exiled anarchist Jack Grancharoff. Around a dozen people listened intently to Jack as he described his upbringing and his involvement in anarchism and the challenges [presented] by both fascism and Stalinism. (The meeting was also a benefit for the Jock Palfreeman Defence Fund.)

In the early 20th Century, anarchism entrenched itself as a mass organisational movement in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland – anarchists having already been active in the 1873 uprisings in Bosnia and Herzegovina against Austro-Hungarian control. But it was primarily in Bulgaria and its neighbour Macedonia that a remarkable case of anarchist organising arose, in the midst of the power-play between the Great Powers. This was the area of conflict where Jack focused much of his early talk on.

Growing up in the midst of poverty, Jack began to challenge authority in his school, soon being expelled and according to his own words was an anarchist before he even knew it. Working as a shepherd in the midst of various invasions, starting with the Nazi and later the Soviet, Jack was expelled from one village after another before coming across anarchists for the first time while being incarcerated in a Soviet concentration camp for a couple of months for being an ‘enemy of the people’.

This poorly-studied movement not only blooded itself in national liberation struggles and armed opposition to both fascism and Stalinism, but developed a notably diverse and resilient mass movement, the first to adopt the 1926 Platform of the Ukrainian Makhnovist exiles in Paris as its lodestone. For these reasons it is vital that the revived anarchist-communist movement in the new millennium re-examine the legacy of the Balkans.

The discussion provided a rare opportunity to hear about and to discuss a little known, but critically important, chapter of anarchist history: the ‘Bulgarian Commune’ of 1944/45. Jack was a participant in those events, as well as knowing the rich variety of characters and organisations that were a part of the events leading up to 1945.

According to Jack, ‘Anarchism succeeded in becoming a popular movement and it penetrated many layers of society from workers, youth and students to teachers and public servants. The underground illegal activities of the movement continued.’

The Bolshevik ‘Red Army’ rolled in at the end of WWII and destroyed what had been organised with the help of the anarchists of the region, just as the Stalinists had done during the Spanish Revolution in the Aragon region, almost ten years earlier. Jack was later forced to flee, first to Italy where he met Italian anarchist partisans and later to Australia where he found work in forestry in Queensland. Jack soon came into contact with Spanish and Italian anarchist exiles in Melbourne and was a founding member of Jura Books in Sydney [see comments below] …

[For more information on Bulgarian anarchism, see: The Anarchist-Communist Mass Line: Bulgarian Anarchism Armed. Listen to ‘Anarchism in Bulgaria – 88 yr old exile Jack Grancharoff relates his experiences’ here.]

4)

… The only great speaker from this era I know to be still alive is the 80-year-old Jack Grancharoff, the Bulgarian anarchist who spoke for years, perched on top of a barrel. He ended up with an MA in politics from Macquarie University but was refused even a casual teaching position there, on the grounds that his English was not good enough.

I once introduced him to a former dean of the faculty of commerce at the University of NSW, as the “professor of peasant studies, University of Sofia”.

I asked Jack why the dean reacted strangely to my introduction. “Oh, I used to work here as a cleaner,” he replied.

If only real professors could not only profess but also hold and entertain an audience like these wonderful elocutionists.