[‘Decadence’ by Alex Trotter. Originally published in Drunken Boat, No.2, 1994.]

There is no decadence from the point of view of humanity. Decadence is a word that ought to be definitively banished from history. ~ Ernest Renan

The word “decadence” has been thrown about so much it has become a banality. Authorities or would-be authorities of all kinds (religious or political ideologues, the media) lecture to us about the decline of western civilization. On close examination the meaning of this term, whether used as an epithet or as a badge of honor, turns out to be elusive. In a general sense decadence seems to be connected to fatalism, anomie, malaise, and nostalgia. It describes a falling away of standards of excellence and mastery associated with a bygone age of positive achievement; heroism yielding to pettiness; good taste yielding to vulgarity; discipline yielding to depletion, corruption, and sensuality. A decadent world is one in which originality has ended and all endeavors are derivative, in which pioneers and geniuses have given way to epigones. Decadence has connotations of (over) indulgence in carnal appetites, derangement of the senses, and violation of taboos. It is supposed to be a frivolous pursuit of exotic and marginal pleasures, novelties to serve jaded palates. Decadence makes you think of sin and overripeness.

Physics recognizes a law of decay and decline with universal application to all natural processes. It is called the second law of thermodynamics, or “entropy,” as it was dubbed by the German physicist Rudolf Clausius in 1850. According to this law, there is a natural and increasing tendency in the universe toward disorder and the dissipation of energy. Efforts to arrest the process of decay or reestablish order are only temporary in effect and expend even more energy. Through this inexorable process of entropy, astronomers tell us, the sun will eventually burn out, and the entire universe may well collapse back upon itself in a “Big Crunch” that will be the opposite of the theorized “Big Bang” with which it supposedly began. There’s nothing anyone can do about this cosmic decadence, but the time frame is so immense that there’s no point worrying about it, either. Besides, it’s just a theory. For the purposes of this essay, I will restrict myself to a consideration of the earthbound and largely historical dimensions of decadence.

Health And Disease

In a grand historical sense, the concept of decadence has been used to describe epochs of civilization in biological metaphor, as beings that are born, come to maturity, then sink into senescence and die because they have been condemned “by History” (or God). In this sense decadence is connected to a moralistic as well as a fatalistic vision. The word implies judgment of human experience on a scale of values and measures it against a ‘correct’ or ‘healthy’ standard. Decadence first appeared as a word during the Renaissance (1549 in the English language, according to Webster’s) but its use remained sporadic until the nineteenth century. It can therefore be thought of as primarily a modern concept, and as such it it inescapably linked to the notion of Progress, as its opposite and antagonistic complement.

What lies on either side of Decadence, before or after it, is the myth of a golden age of heroism and (near) perfection. The ancient civilizations tended to place the golden age of their mythologies in the past. Judaism and Christianity (and by extension, Islam) also have a golden age, the Garden of Eden, located in the past. But it is with the monotheistic religions that the dream of cosmic completion was first transferred to the future, in an eschatological and teleological, semihistorical sense. After holding people’s minds in nearly undisputed thrall for centuries, Christian theology underwent a long decay through Renaissance humanism, the Reformation (in particular its unofficial, suppressed antinomian and millenarian currents), and the rationalist, materialist philosophy of the Enlightenment. The French and American revolutions partially destroyed the Christian time line and opened up the horizon of a man-made history. The violent irruption of the bourgeois class into terrestrial political power replaced the inscrutable cosmic narrative written by God and shrouded in grandiose myth with a historical narrative authored by abstract Man and wallowing in the Reason of political ideologies. The dogma of determinism survived, however. Apocalypse, Heaven, and Hell were shunted aside by capitalism, which offered instead its absurd dialectic of progress and decadence. As the nineteenth century unfolded, liberalism, Marxism, and leftism continued with industrial development and the expansion of democracy.

All of the great epochs of civilization (slavery, Oriental despotism, feudalism, and capitalism) are considered by Marxist and non-Marxist historians alike to have experienced stages of ascendancy, maturity, and decline. The Roman Empire is one of the chief paradigms of decadence, thanks largely to the eighteenth-century English historian Edward Gibbon, the most well known chronicler of its decline and fall. The reasons for the end of the ancient world are not so obvious, in spite of a familiar litany of symptoms, most of which have been attributed to economic causes: ruinous taxes, overexpansionism, reliance on mercenary armies, the growth of an enormous, idle urban proletariat, the slave revolts, the loss of the rulers’ will and purpose in the face of rapid change, and — the most obvious and immediate reason — military collapse in the face of the ‘barbarian’ invasions. Can it be said that Christianity’s rise to power amid the proliferation of cults was an integral part of the decay, or was it rather part of a “revolution” that transcended decadence? It is not at all clear that the Roman Empire ended according to an iron law of historical determinism. If that were the case, it is not likely that decadence could be imputed to ‘moral decay.’ The actual collapse of the Western Empire came centuries after the reign of the most depraved emperors, such as Nero and Caligula. And should it be said that the Empire was decadent, while the Republic was not? Both were supported by the slave-labor mode of production, and both were systems of extreme brutality and constant warfare. The notion of progress and decadence, retrospectively applied to this case, implies that the civilization based on slavery was not only tolerable and acceptable, but indeed healthy, in the bloom of its historical youth, and only later became poisoned and morbid.

The same observation applies, of course, to the other ancient civilization of the West — Greece, which was superior to Rome in so many ways because of its democracy and its fine achievements in art, literature, science, and philosophy. The Athens of Pericles is usually considered to have been the high point of that civilization, in contrast to the “decadence” of the Alexandrian or Hellenistic age. But there would have been no Greek art or Athenian democracy without Greek slavery. There is the great tragedy: The beautiful things of civilization have always been built on a foundation of bloodshed, mass suffering, and domination.

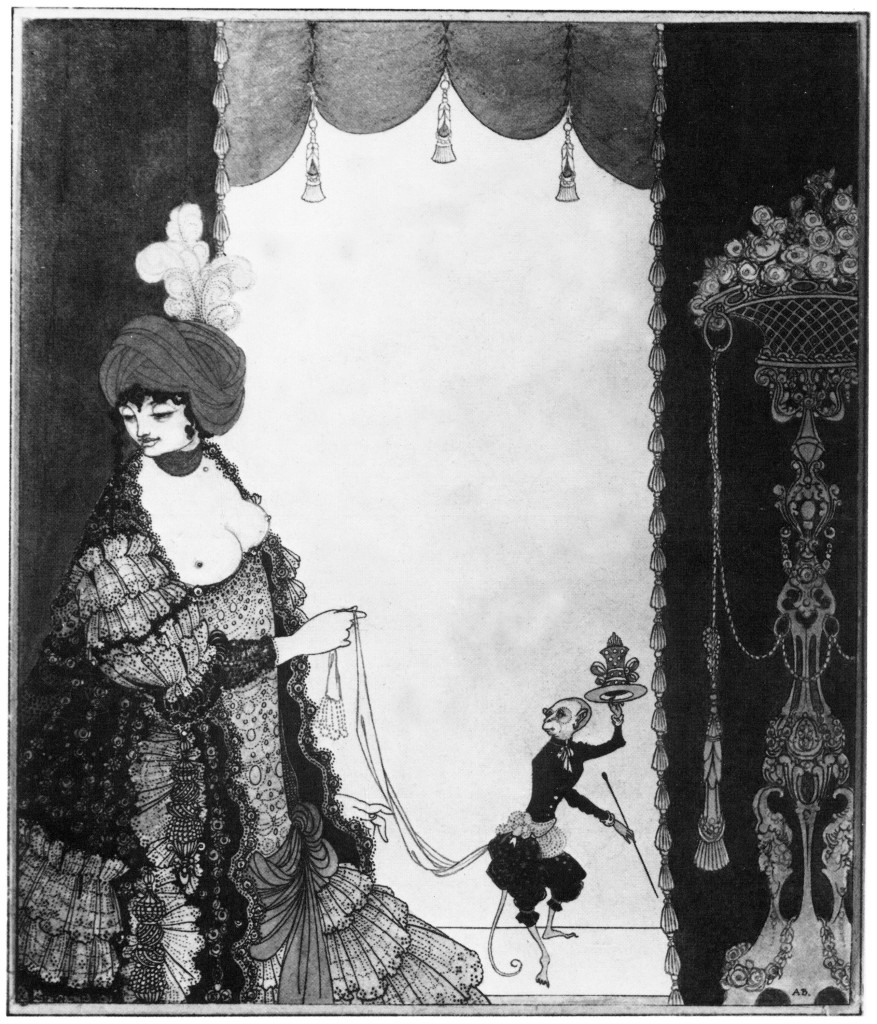

The other great classic of decadence in the grand historical sense is the ancien rĂ©gime in France. This example serves as the core vision, dear to the modern Left, of a tiny handful of identifiable villains, the corrupt, obscenely privileged, and sybaritic aristocrats, oblivious to the expiration of their heavenly mandate, partying away on the backs of the impoverished and suffering masses, but who get their just desserts in the end. This was of course a partial truth, but it was built into a myth that has fueled similar myths well into our own time, the classic modern example being that of the Russian Revolution. The great revolution that chases out decadence has been multiplied more than a dozen times since. But this dream that has been played out so many times is still a bourgeois dream, though draped in the reddest ‘proletarian’ ideology. It is the dream of the Democratic Republic, which replaces one ruling class with another, and it has always turned into a nightmare.

Against the decadence of the old world of the feudal clerico-aristocracy, the Jacobins proclaimed the Republic of Virtue. The mode of cultural representation with which the revolutionary bourgeoisie chose to appear at this time — as a reincarnation of the Roman Republic — deliberately broke with Christian iconography. But it set a precedent for conservative, and eventually fascist, cultural ideology — the identification of social health with the classical, the monumental, and the realistic. The Jacobin regime of emergency and impossibly heroic ideals quickly fell, and the entire political revolutionary project of the bourgeoisie in France was rolled back (more than once) by a resilient aristocracy. But the reign of Capital was assured, for its real power lay in the unfolding, irresistible juggernaut of the economy. This juggernaut was already much further under way in England, while in Germany the bourgeoisie advanced under the banner of philosophy and the arts.