Dan Falcone recently interviewed journalist, blogger, filmmaker, activist and author Antony Loewenstein in East Jerusalem via Skype to discuss his current film project, Disaster Capitalism — inspired by his 2015 book, Disaster Capitalism: Making A Killing Out Of Catastrophe (Verso, 2015), as well as a host of domestic and foreign issues impacting the West, the US and the world. In his film project, Loewenstein provides commentary on US involvement and influence in Haiti, Afghanistan, Gaza, Papua New Guinea and beyond. Loewenstein also draws parallels to Brexit and the national election in the US within his own research and work, and explains how those areas are relevant.

Daniel Falcone: I wanted to first ask you about the film that you’re making, Disaster Capitalism. I know that you’ve spoken a lot about the book, about your thesis, about the argument. Could you just tell me something about the film or where you are in the process of the film and what will the film convey differently from the book, if anything?

Antony Loewenstein: I started working on the book about five years ago, and I started working on the film at about the same time, and initially, I was working on my own. I was traveling to some of these places that are featured in the book, and decided I wanted to do a documentary about it. I didn’t know the shape of what that would look like. In 2012, I partnered with a New York-based filmmaker Thor Neureiter, and he and I have been working together ever since. He’s my film partner and we have been to Papua New Guinea, Afghanistan and Haiti, twice each.

They’re featured in the book as well, but the film is different for a few reasons. One obviously touches on similar issues — people making money from misery, corporations, individuals in countries that are poor or developing. But a lot of the money ended up being unaccountable, and many Haitians themselves say to us, in the film, that “We never saw the money.”

We look at, in the film also — as I do in the book — the role of the Clintons, particularly Hillary Clinton as secretary of state. Bill Clinton, of course — for those who don’t know Hillary and Bill actually had their honeymoon in Haiti in the mid-1970s. I only mention that because they have expressed a love for Haiti for decades, and what that love has actually meant though is, “I believe that Haiti should be exploited.” Until a few years ago, she was the face of putting in power the last prime minister, Michel Martelly, who was a dictator, essentially. He had no qualifications. He used to be a nightclub singer, and I’m not putting down nightclub singers, but he just had no experience in the political arena. The country, basically, has gone to turmoil since.

So the film shows communities, locally, who are suffering, and Papua New Guinea, in Bougainville, which is a small province or country to the north of Australia, it’s a beautiful, beautiful country, incredibly rich with natural resources, but in reality, like so many countries that are so wealthy, it’s incredibly poor because it’s been exploited by Australian and American and Canadian mineral companies, and Bougainville had a huge copper mine — it was the biggest in the world in the 1970s and ’80s — run by the large mineral company Rio Tinto, [which is in both] Australia and London.

There was a huge civil war over this mine. It was one of the most brutal civil wars in that part of the world, between Australia and Asia Pacific for years, but no one’s ever really heard of it. It’s not particularly known.

Outstanding work, thank you, Antony. In shifting gears a bit but perhaps related, how about the Brexit decision and other European countries that might follow suit. How is that pertinent in the realm of disaster capitalism in your estimation?

I think it’s really relevant. You know, I spend time in my book, not in the film, but in the book Disaster Capitalism, I spent quite a bit of time in the UK and looking at particularly the issue of immigration and how immigration is often being privatized and outsourced. What that means is that a lot of detention centers where immigrants are being imprisoned, essentially, run for profit. I think the Brexit decision was an interesting one.

On the one hand, I think the effect of it is going to be very negative for Britain, but at the same time, I had a great deal of sympathy, from a left-wing perspective of why people wanted to leave. I think the majority of people who wanted to leave and voted to leave were not going from a left-wing position from what I’ve read. What I’ve read and spoken to people is that there was profound degree of unease, concern, about the fact that in the last 30 years — which is something I talk about in my book — the British economy has not benefited the majority of the population, and it’s why then immigration is easily blamed for these problems.

So in line of what you’re saying in terms of Trump versus Clinton, the Trump populism, if you will, or his ethno-nationalism, is gathering support in terms of his foreign policy, where he’s trying to take advantage of this mistrust for neoliberals and institutions, and he’s not giving very constructive answers, and his base is given dangerous points of view to real concerns. Can you comment on this?

I agree, and just to be very, very clear again, this is not at all a robust defense of Donald Trump. He is using a clearly strong sentiment of an aspect of predominantly white Americans who feel totally disenfranchised from the US economy. That view is not illegitimate.

I think the people who support him don’t overly care about the fact that there’s not a great deal of detail behind his policies.

Hillary Clinton, to me, is a dangerous demagogue who also has learned nothing from history whatsoever and has made so many bad decisions on Iraq, on Libya, on many other cases. I’m not suggesting that someone like Trump would be better.

Clearly, I think it’d be wonderful that there’s a female president, yes, but surely that’s not the only important issue. How does she see women in Afghanistan? Does she think that Muslim women should be bombed in various Muslim countries? Yes, she does. That’s a less than feminist position.

They’re not leaving us with very good choices in the US; often the case.

Agreed. And if I was American, and I’m not for a second telling you how Americans should vote, I think, at the moment, I would probably vote for someone like Jill Stein who’s of the Green Party, who from what I read, has very interesting policies. They’re progressive.

When looking at a region like Gaza, how can disaster capitalism be pertinent in the Middle East and especially in terms of our relationship with Israel? For example, it seems like a lot of your work — I know you touch on warfare and the consequences of militarism, but it sounds like — what it reads to me as anyway — is your critique of imperialism and resource wars in addition to how we sponsor terrorism or military campaigns across the world, but how about specifically Gaza? Is the west essentially destroying that place only to build it back up and destroy it again and other regions that support the occupation?

The situation in Gaza is incredibly desperate. I have not been there for a few years. I was last there in 2009. I’m now based in East Jerusalem. Gaza is really almost the perfect example of the tacit failure of Israeli and US policy towards Palestinians — that there really is no great desire to resolve this issue. What I mean by that is, the circle status quo that exists between Israel and Hamas, the rulers of Gaza, is Israel doesn’t actually have a great desire to overthrow Hamas. They could overthrow Hamas in a day.

So Israel essentially believes, and the US gives uncontrolled and unlimited amounts of military support, which I might add has increased under Obama. This idea, somehow, that many in the Zionist community argue that Obama has been the worst president for Israel and a disaster, it’s a complete lie. The fact that settlements on the West Bank have no impact on the financial support that Israel has received.

The occupation is going to be 50 years old in 2017, next year. That’s in the West Bank. In Gaza, Israel in theory disengaged in 2005. As I said before, they still control the land, sea and air borders, which was always done in an incredibly bad and poor way, barely touches the surfaces of what Gaza needs.

It’s like an open-air prison. The border with Egypt is sealed virtually 99 percent of the time. The border with Israel is also mostly sealed. Very few Gazans can get in and out. So the effect that Israel, and with US and Western support, is backing, and funding and arming a permanent open-air prison, for no real strategic benefit, let alone humanitarian relief. It really depends how one views the Israel-Palestine conflict.

A lot of the Americans, when they watch the news media coverage of the Middle East, and they’re presented with a sampling — don’t really have an understanding of who the Palestinians are. They don’t know much about the Palestinians, but they see, I think, isolated acts of violence perpetrated by Palestinians against Israeli soldiers, and it’s a separate point to Israel “mowing the lawn,” or barricading a place like Hebron, the city that they recently did indeed block off. In other words, separate from the Israeli policy, there seems to be this marriage between what Israel does as justified because they are on the receiving end of Palestinian terrorism.

And people aren’t really able to distill the fact that Israel policy is going to carry on no matter what happens, whether there’s a stabbing, a kidnapping, an explosion, etc. People are correlating Israeli policy with actions of people on the other end of this for years. This isn’t just a media culture, but it’s in the educational system, higher education and people that study international relations. What do you think about the corporate media structure and how it delivers this picture to American society from the standpoint of what’s happening to the Palestinians?

Well, certainly, 9/11 has made this far worse, and even before then, but certainly become a lot worse since 9/11 in your country. The framing of the Israel-Palestine conflict is usually like this: Israel is defending itself. Israel was sort of sitting here minding its own business. Palestinians are aggressive. They’re angry. They’re stabbing us. They’re killing us. They’re blowing up buses in Tel Aviv. They hate us because we’re free, because we’re Jews, because we’re a democracy, whatever it may be.

That’s a fundamentally wrong and racist view. There’s no doubt that there is Palestinian violence against Israel. Yes, it happens. There are — not so much these days, but there have been suicide bombings and stabbings, and any attack, to me, against civilians is fundamentally wrong, and should stop. There’s an occupation that is happening. I’m living here in East Jerusalem. It’s happening right here, and it’s happening right down the road.

So in Israel the rhetoric — and in the US too is — Hamas, Hezbollah, ISIS, Al-qaeda are all the same thing. They’re framed in all the same way, so when there’s, for example, a beheading of a journalist in Syria, or Iraq, by ISIS the last couple of years, many in the Israeli political elite and the media automatically tie that, and they say, “You see. The Arabs, they’re crazy.”

We’re still at a stage, in 2016, where we’re actually — are we not accepting it’s an occupation? Are we saying that it’s not permanent? Fifty years is permanent.

What are your thoughts on something like the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Movement (BDS) or the impact of the lobby? A lot of the criticism of Israel that I read shows the left sort of having these divisions within the progressive side in terms of criticizing the United States’ support of Israel and the occupation. How influential is the lobby? Are we more concerned with government decisions, media structures, or is the lobby the influential interest group? I see differences of opinion in terms of what question should we be asking and where do we apply a critical focus.

Also, in BDS, there’s a disagreement there too. How pertinent is BDS? Is that the most constructive response? I just see members of the left wing that are — I wouldn’t say feuding, but they disagree on the effectiveness of BDS, where do you come down on this?

Okay, two points there. There’s no doubt the Israel lobby is influential. It has power. AIPAC, which is America’s largest Israel lobby, at its conference a few months ago, and you see it’s powered by the people that are speaking there, which is pretty much all the top political leaders on the Democratic and Republican side, hundreds of Senators come, thousands of delegates, Jews and non-Jews, mostly Jews, but others too. They have influence. They have power. There’s no question about that. They push a very hardline position.

There are small groups. The group Jewish Voice for Peace is one that I have a lot of time for. They’re a lobby group of sorts. They’re liberal Jews. They’re based around the US. They have, I think, about 100,000 people signed up. They speak out very forcefully about occupation.

Let’s not forget, BDS was established, officially, in 2005 by Palestinian Civil Society, essentially saying to the world, “We’re living here under occupation. We’re asking you to please help us by not supporting any institution within Israel. That could be cultural. That could be academic.”

I think there is a desperate attempt now, in the US, to make BDS illegal. I don’t think we’re that far away from a very important test case that I suspect will go to the Supreme Court.

We’re talking about criticizing a policy which demonizes Palestinians for over half a century. Within Israel itself, BDS is not supported by the majority of Israel Jews. There’s no question about that.

Thank you, very much.

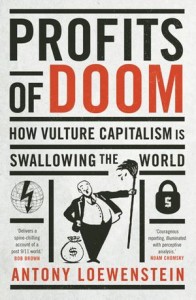

Vulture capitalism has seen the corporation become more powerful than the state, and yet its work is often done by stealth, supported by political and media elites. The result is privatised wars and outsourced detention centres, mining companies pillaging precious land in developing countries and struggling nations invaded by NGOs and the corporate dollar.

Best-selling journalist Antony Loewenstein travels to Afghanistan, Pakistan, Haiti, Papua New Guinea and across Australia to witness the reality of this largely hidden world of privatised detention centres, outsourced aid, destructive resource wars and militarized private security. Who is involved and why? Can it be stopped? What are the alternatives in a globalised world?

Vulture capitalism has seen the corporation become more powerful than the state, and yet its work is often done by stealth, supported by political and media elites. The result is privatised wars and outsourced detention centres, mining companies pillaging precious land in developing countries and struggling nations invaded by NGOs and the corporate dollar.

Best-selling journalist Antony Loewenstein travels to Afghanistan, Pakistan, Haiti, Papua New Guinea and across Australia to witness the reality of this largely hidden world of privatised detention centres, outsourced aid, destructive resource wars and militarized private security. Who is involved and why? Can it be stopped? What are the alternatives in a globalised world?

The 2008 financial crisis opened the door for a bold, progressive social movement. But despite widespread revulsion at economic inequity and political opportunism, after the crash very little has changed.

Has the Left failed? What agenda should progressives pursue? And what alternatives do they dare to imagine?

The 2008 financial crisis opened the door for a bold, progressive social movement. But despite widespread revulsion at economic inequity and political opportunism, after the crash very little has changed.

Has the Left failed? What agenda should progressives pursue? And what alternatives do they dare to imagine?

The Blogging Revolution, released by

The Blogging Revolution, released by  The best-selling book on the Israel/Palestine conflict,

The best-selling book on the Israel/Palestine conflict,