By Ray Bennett

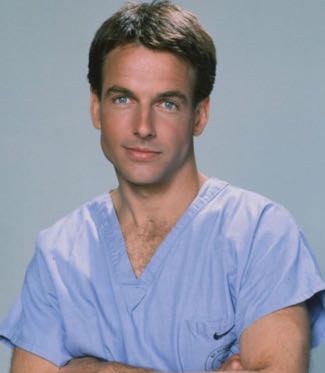

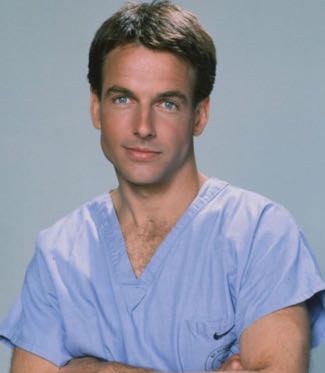

LONDON – I first met Mark Harmon, who turns 65 today, when he was 29 years-old and it was clear then that he had the talent and determination to become one of the most enduring and popular stars on American television.

Few TV stars can match his longevity from “Flamingo Road” to “St. Elsewhere” (below) to “Reasonable Doubts” to “Chicago Hope” and his long-running current hit series “NCIS” (above) with many feature films, TV movies and other series along the way.

Harmon was among the first people I came to know when I started to make regular visits to Hollywood to write stories for TV Guide Canada in the early Eighties. I’d stop by his little house in Studio City or we’d meet at Du-Par’s restaurant and bakery on Ventura Boulevard. Often, he’d be in the company of actress Cristina Raines (pictured with Harmon below), whom he was dating at the time, and that was just fine because like any young man who’d seen her as Keith Carradine’s girlfriend in Robert Altman’s “Nashville”, I was a little bit in love with her too.

I’d stop by the Warner Bros. set of the primetime soap “Flamingo Road”, in which they both starred, and chuckle over the reaction of co-star Morgan Fairchild. Harmon told me, “She can sense that there’s a member of the press here and she can’t figure out why you’re not talking to her.”

I’d stop by the Warner Bros. set of the primetime soap “Flamingo Road”, in which they both starred, and chuckle over the reaction of co-star Morgan Fairchild. Harmon told me, “She can sense that there’s a member of the press here and she can’t figure out why you’re not talking to her.”

One time, he invited me to join him and Raines at Faulkner’s Falcon Studio on Hollywood where former Olympic fencer Ralph B. Faulkner had for decades taught actors such as Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Errol Flynn how to sword-fight in the movies.

The young actor took such instruction very seriously. He said, “Acting is photographed movement. To be able to move is really important. Put Errol Flynn on a screen and, I tell you, he’s magnetism; he’s incredible to watch because he moves so great. Astaire and Rogers. That’s where my head is at because that’s what it’s all about. That’s what I’m trying to do, to be prepared to do anything I get the chance to do when the opportunity arises. It’s a waiting game and you gotta learn how to wait, and when you get the chance you’ve got to be ready. If you’re not ready, who cares? Somebody else who looks just like you and is just as talented, maybe more talented, he’ll do it. People fall by the wayside. I’m a competitive person. I’m a disciplined person. That goes ’way back.”

Harmon was born in the shadow of his father, an American football legend at the University of Michigan and the Los Angeles Rams, who became a successful broadcaster. Mark told me, “‘When I hit my first home run in Little League, when I was nine, people said, ‘Well, he’s Tom Harmon’s son.’ When I went to college and started playing football, people said, ‘Oh, Pepper Rogers gave Tom Harmon’s kid a scholarship, isn’t that terrific.’ I could never understand that logic. My Dad raised me real tough and he made damned sure that whatever it was I wanted, I worked for it, and I did. My mind is real clear about that. Nothing was ever given to me to me.”

If he wanted to play catch with his father, he had to wait, hopeful that, when he got home Sunday night after a road trip and a broadcast, it was still light out: “I didn’t just throw the football, either. I hit right shoulder, left shoulder, ear, ear, chin. Baseball, the same. When I threw one in the dirt or threw one high, he went inside. That was it. I’m talking an 8 year-old kid with amazing control.”

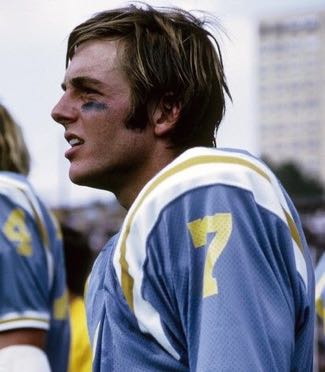

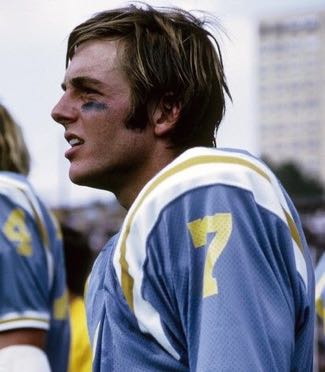

He sensed even then that his father was breeding a competitive spirit in him: “He would always push a bit more but he was smart enough to know that I responded to that. Think about this: I was 17 years-old before I beat my Dad in a 40-yard run. My first game for UCLA against Nebraska at the Coliseum, all he told me was ‘Relax, have fun, play your game.’ We beat them and when I came out of the locker room, he was just leaning there. There were a lot of people around. I looked at him and he said, ‘Hey.’ He smiled and he said, ‘Great game!’ I just started crying. I ran to him and he started crying.”

Acting, he said, was not an option, it was a deliberate choice. He had done national commercials and print work from the time he was aged 6. He entered speech contests and did stage plays: “I knew I wanted to do that. It was great to get up and entertain people. People would ask, ‘What do you want to do?’ I’d say, ‘I want to go to the biggest school I  can go to and compete.’ It turned out to be UCLA (right) and it was a wonderful experience. I played athletics in college but I played for different reasons than a lot of people there. To put on a uniform and run around in front of 80,000 people on a Saturday, that was a kick.”

can go to and compete.’ It turned out to be UCLA (right) and it was a wonderful experience. I played athletics in college but I played for different reasons than a lot of people there. To put on a uniform and run around in front of 80,000 people on a Saturday, that was a kick.”

He knew that he could make good money playing football: “When I was a senior at UCLA, the WFL was in full swing and the CFL and the NFL were getting into horrendous bidding wars for athletes because there was only a certain number of players who were available. I’m not saying I could have made the team, any team, in any of the leagues. But I am saying that I could have gone to camp and received bonus money that was incredible at the time. They were offering big bucks and when you’re 20 years-old, to turn down $40,000 just for reporting to camp was an awesome decision. It was for me. The guys who were my friends, 19 kids that I played with were drafted and went on to play professional football. Every one of them made more in six months than I made in three years. Now, only two of them are still playing so the thing evens out and I’m sitting here saying ‘knock on wood’. But there was a whole lot of time when the decision was anything but brilliant.”

He did not, however, jump right into a role on TV: “I took a job in an advertising firm. I studied acting all the time. Advertising was a good arena to study people and it gave me the money to study acting at night, which is what I did for one year and two months, two different jobs. I could have tried carpentry but I wouldn’t have gotten the dollars I got from advertising, and the acting classes, the fencing lessons, and ballet lessons were expensive. Then I decided it was time to make the commitment. When I quit the advertising job there weren’t many people I knew who didn’t think I was out of my mind but I quit my job, sold my house, sold my car and hung in there.”

Bit parts led to bigger roles and then came “Flamingo Road”. Then in it’s second season, Harmon remained clear-eyed about it: “In comparison to other shows that have been cancelled, it’s not getting the numbers that qualify it to stay on the schedule. That’s the fact of the matter. So, if it stays on the air, great; if it doesn’t, you know, there’s always tomorrow.”

Bit parts led to bigger roles and then came “Flamingo Road”. Then in it’s second season, Harmon remained clear-eyed about it: “In comparison to other shows that have been cancelled, it’s not getting the numbers that qualify it to stay on the schedule. That’s the fact of the matter. So, if it stays on the air, great; if it doesn’t, you know, there’s always tomorrow.”

He enjoyed the work: “It’s a nice family on the show. I go to work each day and I get to work with people like Kevin McCarthy and Howard Duff. I couldn’t get educated like that in any classroom across America. They’re wonderful people. I fight real hard to keep it in perspective, and say, OK, that’s alright, the learning experience was in the chance, not necessarily in the finished product.”

His idols, he said, were old time movie stars: “When I saw William Wellman’s ‘Wings’ when I was 6, I was Buddy Rogers flying that airplane. That’s the kind of stuff I want to do. I watch a lot of old movies on TV. I’m a great fan of the bottom 10 in the Nielsen ratings. The actors I admire the most are the ones who are so damned natural on the screen. They work so hard that the ‘act natural’ thing comes across. The trick is to be natural and not let the effort show. Directors at first complained about Gary Cooper, ‘When will he start acting?’ but the point is that when he was on screen, you couldn’t look at anybody else.”

What he loved about the business, he told me, was the insecurity: “As an actor, you have to be asked to exercise your talents. It’s not like writing or sculpting or painting. You can’t do it without somebody else asking you to do it. It’s a waiting game and it’s real important to learn how to wait. I hope I’ve learned how. I’ve always had a game plan. I’m a big dreamer. I dream big, in colour. That’s an advantage and a disadvantage. I don’t think I’ve been pleased with much of anything I’ve done. Maybe I won’t ever be.”