Rough waters for container shipping. Why Hanjin, the world’s seventh largest container line, went under

Olaf Merk, Ports and Shipping expert at the International Transport Forum (ITF), OECD. We are co-publishing this post with the ITF’s Transport Policy Matters blog

Sad news. After months – even years – of pain and suffering, the South Korean container shipping company Hanjin finally sank and passed away. Not just any casualty, but the largest shipping bankruptcy in history: Hanjin was the world’s seventh biggest container line with a fleet of 90 ships. Was this an accident, an isolated case of bad luck, or is something more structural going on?

Like with any bereavement, there are the immediate arrangements to make. Terminal operators and maritime service providers were not paid for their services and need their money, so they have seized Hanjin ships in ports to have some sort of guarantee. Hanjin’s clients are eager to know that their goods will be delivered and not be stuck on ships. Competitors are circling around the deceased to pick up some of the ships that Hanjin leaves behind.

At the same time, people are starting to wonder how all this could have happened. Forensic analysts talk about the sluggish demand for container transport, hit by declining trade from China, the overcapacity in container shipping and the resulting low ocean freight rates that have made it very difficult to make profits in container shipping. All this sounds very logical, but also pretty abstract, and – more fundamentally – it obscures an uncomfortable truth: this was not an accident, but market forces at play – and it will happen again.

The story starts – in a way – in a corporate boardroom in Copenhagen in 2010. Then, the world’s largest container shipping company, Maersk Line, decided to order a set of new container ships that were larger than the world had ever seen, able to carry 18,000 standard containers. Putting more containers on a more fuel-efficient ship would save costs and thus give it a better position in a very competitive market.

For a weekly container service between Asia and Europe – the route on which the largest ships are deployed – ten to eleven ships are needed; a lot of capital that smaller companies would not be able to collect. As the order for the new mega-ships was placed while the global economic crisis was still unfolding, banks were unwilling to lend much to a risky business like shipping, especially the smaller ones with high risk profiles. Timing was excellent, with ship prices low due to overcapacity in shipbuilding yards. The new mega-ships were smartly marketed as “Triple E” ships, providing economies of scale, energy efficiency and environmental performance. They also provided a once in a lifetime opportunity “for the market consolidation that big players hoped for“.

Yet things worked out differently: other firms reacted by ordering similar mega-ships and by organising themselves in alliances. They agreed to share slots on each other’s vessels, which means they can offer networks and connections that they would not be able to offer if they would go it alone. Alliances had existed before, but the Triple E-strategy involuntarily resulted in stronger alliances in which more carriers were involved. These consortia were also used to share newly acquired mega-ships, so individual carriers would only need to buy a few of these, instead of having to shoulder a whole set of ten ships. Consequently, many carriers were able to rapidly catch up and also order mega-ships, many more than expected. The alliances became such powerful mechanisms that even the largest companies found themselves forced to find alliance partners.

This gave a different twist to the play, but with a similar outcome. The combined mega-ship orders in a period of sluggish demand created a sensational amount of overcapacity: way more ships than were needed. This overcapacity resulted in lower freight rates, lower revenues and several years of losses, which we have not started to see the end of yet. Whoever has the longest breath and biggest pockets will survive; the others won’t and will suffer death by overcapacity, like Hanjin.

There will very likely be more Hanjins. Hardly any container shipping line is making profit nowadays and the perspectives are bleak. Sputtering trade growth and gigantic ship overcapacity will continue to depress ocean freight rates. Banks, creditors and governments might well get impatient with some of the liners and cut life lines again.

Economic theory champions the notion of “creative destruction”, in which inefficient firms are replaced by more efficient ones. So, even if it is hardly any comfort for employees that lose their jobs in the process, one could consider it a natural thing that weaker shipping firms disappear.

There is just one problem. If this process continues, it will soon lead to a very small group of powerful carriers dominating an already concentrated market, enabling them to put a lot of pressure on clients and ports. We are starting to see what the results of this are: less choice, less service and fewer connections for shippers, the clients of shipping lines. The ports that accepted the offer they could not refuse and invested in becoming mega ship-ready may find out that they placed their fate in the hands of a few big players who frequently change loyalties at fast as the wind.

Hanjin is gone; the problem is still very much there.

Useful links

The impact of mega-ships Olaf Merk on OECD Insights

The Hanjin case is a practical illustration of the complexity of sectors such as international shipping. The OECD is organising a Workshop on Complexity and Policy, 29-30 September, OECD HQ, Paris, along with the European Commission and INET. Watch the webcast: 29/09 morning; 29/09 afternoon; 30/09 morning

Air pollution: Tyre and brake fatigue compound an exhausting problem

Shayne MacLachlan, OECD Environment Directorate

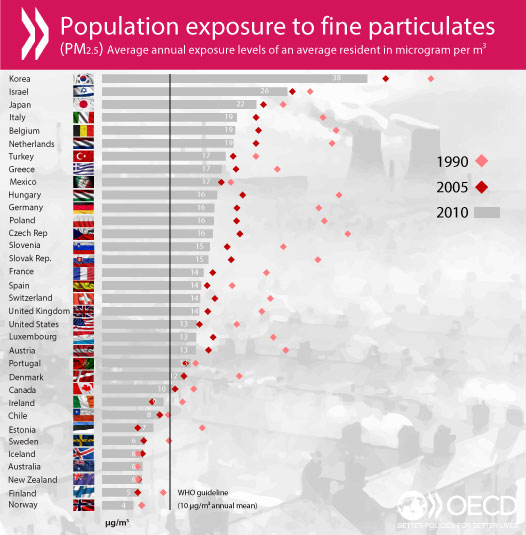

Anyone else feeling exhausted by all this drum humming about air pollution? Indeed it appears the fumes won’t be dissipating any time soon as we consider the extent to which tyre and brake rubbish exacerbate the problem. The European Commission says exhaust and non-exhaust sources may contribute almost equally to total traffic-related PM10 emissions. A few months ago, I was proposing (on this very Insights blog) that electric cars are essential in fighting filthy air pollution in urban areas because humans are unwilling to relinquish the comfort of their vehicles. Since then, I find myself mulling hard after this “alarmingly obvious” realisation that electric cars use tyres and brakes too! Even if they emit less of the harmful fine particles than conventional vehicles, please do feel free to file that blog in the “seemed like a good idea at the time” folder. And to turn insult to injury, I see that my own colleagues at the OECD have just published new data on PM2.5 emissions which did little to ease my blushes.

Fine particles vs coarse particles

A lot of non-exhaust pollution from tyres and brakes winds up in rivers, streams and lakes. They produce particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) which is more harmful for humans than gas pollutants like ozone and NO2. Fine particulate matter penetrates deep into your lungs and cardiovascular system. New research has even discovered tiny particles of pollution inside samples of brain tissue. The OECD is amongst a few international organisations proudly leading the fight against ambient air pollution. And rightly so, with 80% of the world population exposed to PM2.5. Outdoor air pollution causes 3.7 million premature deaths a year and 1 in 8 people die from filthy air. OECD Environment Director, Simon Upton recently stated that air pollution is not just an economic issue, but also a moral one. He urges governments to stop fussing over the costs of efforts to limit pollution and start worrying more about the even larger costs they will incur if they continue to allow it to go unchecked.

Dead “tyred” but rolling on

Tyre rubbish is the 13th largest source of air pollution in Los Angeles, California, a city famous for its smog. A recent study showed links between PM2.5 particles and the daily death rate in 6 Californian counties. When the PM2.5 count was high, so was the death rate. Then there’s nanoparticles, ultrafine particles used in tyres. Manufacturers didn’t know it at the time but research now contends possible links to lung cancer from recycling some of the 1 billion dead tyres used in, for example, the surfaces of playgrounds. Some are calling it “the new asbestos”. The complexity of the problem is evident: there are over 1 billion cars on the road globally and on top of that just as many motorbikes and scooters. Add to that the pneumatic tyres used on trucks and public transport such as metro train systems and buses and we have a considerable source of road rubber. A road with 25,000 vehicles using it each day can produce up to nine kilograms of tyre dust per kilometre. That’s only ¼ of the 100,000 cars that use the Champs-Elysées each day so that makes at least 36 kilograms of tyre pollution a day on the world’s most famous street.

Bliss ignorance until my tyre burst

When I think back 10 years, sharing my time between the “not so clean” cities of London and Paris, I really had no idea that the air in these places was so bad. I recall often emptying my nostrils of its black contents after using underground transport, but now learning about the added impact of tyre and brake rubbish, I’m not really sure being better informed is better—at least from a personal health standpoint. I have friends in Paris that actively avoid Châtelet and other central metro stations for a number of reasons, one of those being the eye-watering pollution. The metro trains’ brakes and tyres are contributing to this “perfect pollution storm in a subterranean teacup”. Sometimes you can find between 70-120 micrograms of PM10 per m3 down there with peaks at 1,000 micrograms per m3 trapped in the station. In comparison, the average concentration of PM10 outside is around 25-30 micrograms per m3.

So what can we do?

In an ideal world, we would ditch cars completely, but I’m not sure we’re ready to take that step yet. However, several cities are working on implementing policies that will ban or severely reduce the amount of cars. Oslo announced a plan to ban all cars from its city centre in 2019; and Norway is in the process of preparing a bill that would issue a nation-wide ban of the sale of petrol-powered cars. In places such as Tuscany, cars are banned in city centres except for residents. Others park their car just outside and then take public transport. This is common in the UK too. This means that when there are more people in the centre during the day, there are fewer cars, meaning fewer people are exposed. Hopefully, other cities and nations will be inspired by such drastic changes in transportation methods and follow suit. There are certainly enough reasons to do so.

Play the cards dealt and work towards a better hand

It’s hard not to feel we’ve exhausted our current options. I’ve gone through several cycles of choosing my methods of transportation and have ended up cycling—literally and figuratively. Do bicycle tyres contain rubber (though they emit precious little)? Yes; and so do bus and some metro train tyres, as well as motorbikes and scooters. We are left with only imperfect options. They won’t solve the problem, but they can reduce it and that’s something to be optimistic about. As with many actions that influence health and the environment, human behaviour and choices matter massively. Choosing the least damaging option of getting around your town means the bicycle is still a great option. It might also be worth trying to avoid times in which the pollution levels are the highest: 9h, 12h and 18h in many cities. But of course the exercise and associated heavy breathing whilst riding, exposes you to the risk, even though you are contributing least to the problem. So while the thought of all that damaging pollution is ever so “tyring”, it seems that the pollution, including from brakes and tyres itself might also leave you feeling worse for wear.

An international deal on air pollution

WHO guidelines indicate that by reducing PM10 pollution from 70 to 20 micrograms per m3, air pollution-related deaths could be reduced by roughly 15%. Staging a climate COP (Conference of the Parties) style conference to address air pollution emissions seems like a good start. Who could disagree that setting limits for polluting emissions from all sources is an absolute minimum requirement to give our lungs and environment a breather. Moving forward, it’s crucial we keep pushing governments to come up with innovations and policies that vigorously tackle air pollution issues. Governments also need to ensure that people are aware of the issues and help them make the best choices. In the meantime, we all have to play the cards we’re dealt and make a conscious effort to choose least polluting options.

Useful links

The Economic Consequences of Outdoor Air Pollution

Health Impacts of Road Transport

OECD data on emissions:

A dash of data: Spotlight on Australian households

Economic growth (GDP) always gets a lot of attention, but when it comes to determining how people are doing it’s interesting to look at other indicators that focus more on the actual material conditions of households. Let’s see how households in Australia are doing by looking at a few alternative indicators.

GDP and household income

Real household disposable income per capita increased 0.9% in Q1 2016 compared to the previous quarter (the index increased from 113.7 in Q4 2015 to 114.7 in Q1 2016), outpacing GDP per capita which increased 0.6% from the previous quarter (the index increased from 108.1 in Q4 2015 to 108.8 in Q1 2016). The rise in household disposable income mainly reflected a growing compensation of employees and income from self-employment, and – to a slighter extent – an increase in interest received by households.

This recent development continues the trend observed since the first quarter of 2007. Indeed Australian real household disposable income per capita has grown considerably more than real GDP per capita: 14.7% versus 8.8% (chart 1). The growth in household income over that period partly reflects government interventions during the first years of the crisis which, it is worth noting, did not impact the Australian economy as severely as it did other OECD countries. Even though there was a dip in economic activity in Q4 2008, the Australian economy was never formally in recession (defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth).

Chart 2 shows that net cash transfers to households increased sharply at the start of the financial crisis, mainly due to increases in social benefits. Since the peak in Q2 2009, net cash transfers to households exhibit a downward trend corresponding to the time period when economic growth and household disposable income have started to move (more or less) in tandem.

Confidence, consumption and savings

Household disposable income is a meaningful way to assess material living standards, but to get a fuller picture of household economic well-being, one may also want to look at households’ consumption behaviour. Consumer confidence (chart 3) remained broadly stable at 99.7 in Q1 2016. This contributed to sustaining real household consumption expenditure per capita which increased by 0.3% in Q1 2016 (the index increased from 107.7 in Q4 2015 to 108.0 in Q1 2016) (chart 4).

The households’ savings rate (chart 5) shows the proportion that households are saving out of current income. In Q1 2016, the savings rate ticked-up to 15.8% showing that households chose to save some of their additional income, rather than spending it on goods and services. Overall, Australian households have a relatively high savings rate. Over the whole period observed, the average rate is 16.2%, one of the highest among OECD countries. In Q4 2008, the savings rate increased sharply, to its highest level (19%), partly reflecting households’ responses to deteriorations in financial markets and an increased level of uncertainty over future income.

Debt and net worth

The households’ indebtedness ratio, i.e. the total outstanding debt of households as a percentage of their disposable income, may reflect (changes in) financial vulnerabilities of the household sector and provides a useful yardstick to assess their debt sustainability. In Q1 2016, household indebtedness increased to 198.5% of disposable income (chart 6), doubling over the past 20 years and one of the highest levels among OECD countries. This rise in household’s indebtedness followed the introduction of mortgage packages in the 1980s and 90s, which allowed homeowners to draw down on their mortgages when needed, without having to sell their house. In addition Australian households have increasingly borrowed money to finance house purchases (Chart 6).

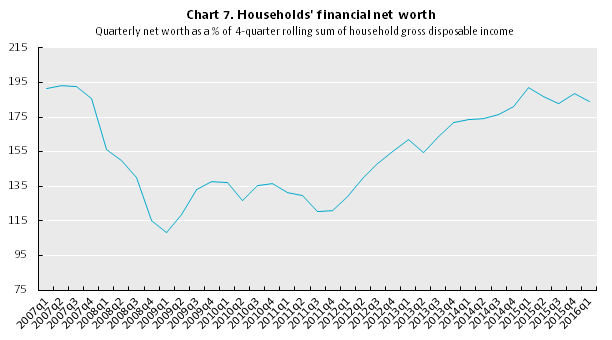

When assessing households’ economic vulnerabilities, one should also look at the availability of assets, preferably taking into account both financial assets (saving deposits, shares, etc.) and non-financial assets (for households, predominantly dwellings). Because information on households’ non-financial assets is generally not available on a quarterly basis, financial net worth (i.e. the excess of financial assets over liabilities) is used as an indicator of the financial vulnerability of households.

In Q1 2016, financial net worth of households was 183.9% of disposable income (chart 7), 4.9 percentage points less than in the previous quarter. This decrease was predominately driven by the rise in household debt (chart 6), and holding losses on pension assets, equity and investment fund shares.

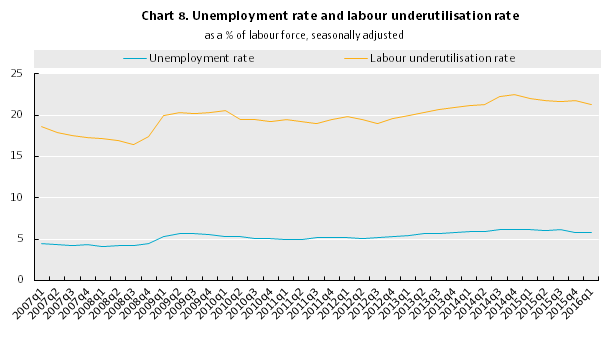

The unemployment rate and the labour underutilisation rate (chart 8) also provide indications of potential vulnerabilities of the household sector. More generally, unemployment has a major impact on people’s well-being. In Q1 2016 the unemployment rate in Australia remained at 5.8%, while the labour underutilisation rate, which takes into account underemployed workers and discouraged job seekers, decreased slightly to 21.3% (from 21.8% in Q4 2015). Notwithstanding this small decline, the gap between the unemployment rate and the labour underutilisation rate remains large in Australia – the largest among OECD countries, indicating unmet aspirations for more work among Australian workers.

One should keep in mind that households’ income, consumption and savings may differ considerably across various groups of households; the same holds for households’ indebtedness and (financial) net worth. The OECD is working on these distributional aspects and preliminary results can be found here and here. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has also a long history analysing households’ developments broken down by income and household characteristics.

Overall, the first quarter of 2016 saw a continued increase of Australian households’ material well-being with still expanding income and consumption per capita. The upward trend in the household debt-to-income ratio and the high labour underutilisation rate – reflecting the challenge for some groups of workers to bounce back after displacement – remain a source of concern. Despite increasing household debt, financial net worth is slowly getting back to its pre-crisis level. However, to fully grasp people’s overall well-being, one should go beyond material conditions, and also look at a range of other dimensions of what shapes people’s lives, as is done in the OECD Better Life Initiative.

Useful links

For many years, OECD has been focusing on people’s well-being and societal progress. To learn more on OECD’s work on measuring well-being, visit the Better Life Initiative.

Interested in how households are doing in other OECD countries? Visit our household’s economic well-being dashboard.

How to Assess China’s G20 Presidency

Noe van Hulst, Ambassador of the Netherlands to the OECD

Noe van Hulst, Ambassador of the Netherlands to the OECD

It was a unique event, for sure: China hosting its first G20 summit in Hangzhou on 4-5 September. The city where Chinese leader Mao Zedong half a century ago regularly met with Third World guerrilla leaders to discuss the battle against US “imperialism”. China has come a long way since then, now leading the G20 push to escape from the “low-growth trap”, stalling globalization and the tide of rising protectionism. With growth persistently too low and trade even lagging this low rate, it is time for more decisive policy action. The overall result in the final communique has been coined The Hangzhou Consensus: linking a vision based on innovative, sustainable economic growth and a well-balanced policy mix with forcefully tackling inequalities and promoting an open global economy. It is encouraging to see China make the case for a rules-based global system of open trade and investment. Of course, this commitment also should have important consequences for domestic policies in China, as well as in other G20 countries. In this context, it’s a remarkable step that G20 leaders have now agreed to tackle the excess capacity in the steel market.

What was striking in China’s approach to the G20 presidency is the welcome focus on medium- and long-term structural economic policies, in combination with an orientation on policy-action. Trade and investment moved up on the policy agenda, resulting in a G20 Strategy for Global Trade Growth and G20 Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking. Completely new was the emphasis on innovation, digital economy and the New Industrial Revolution, nicely brought together in a G20 Blueprint on Innovative Growth. In addition, there was a drive to deliver an Enhanced Structural Reform Agenda, identifying priority areas for structural reforms and monitoring a new set of quantitative indicators.

As always, implementation will be key, especially on reversing adverse trends in trade, investment, structural reform and Internet control. Although these elements were in my view the most remarkable, of course many other policy areas have also been advanced: taxation, finance, employment, entrepreneurship, sustainability, energy, green finance and climate change. The announcement by both China and the US of their ratification of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change was widely welcomed as an important step in the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Another remarkable factor about China’s G20 presidency is the continuing important role of the OECD Secretariat. Although China is not a member of OECD, it nevertheless relied substantially on the analytical support and assistance of the OECD Secretariat in a substantial number of key areas, e.g. innovation, trade and investment, structural reform, employment, inequality, green finance and taxation. This can be interpreted as an important sign of appreciation for the quality of the work. We can observe a welcome rapprochement between China and the OECD Secretariat, as well as with the IEA in the energy field. The OECD Secretariat also showed laudable flexibility and adaptability in responding timely to the G20’s call to pull together a new Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS), which now has 85 countries, including many developing countries, committed to the BEPS roadmap.

Of course, much work is still ahead of us. Apart from the existing work streams, the OECD is tasked with taking forward the work on innovation/digital economy, overcapacity in the steel market (within a new Global Forum led by OECD) and designing tax policies for inclusive growth, among other things. The Netherlands views the supporting role of the OECD Secretariat in the G20 as very useful, as it provides non-G20 OECD countries an important window on and bridge to the G20.

Where is the G20 heading? Created as a mechanism for crisis management, it is now moving in the direction of a “steering committee” of the global economy. China’s emphasis on medium- and long-term structural policies has been helpful in this respect. Some observers express disappointment with the G20’s effectiveness in the face of persistent weak growth and a widely proliferating G20 agenda. This is partly understandable, in particular where it comes to insufficient implementation of agreed G20 commitments, like on trade and structural reform. That’s why structural policy measures following the 2014 G20 commitment to raise global GDP by an additional 2% by 2018 have so far only resulted in 1% according to OECD and IMF calculations. And it has been widely reported that G20 protectionism has been on the rise, contrary to what has been agreed. However, as the G20 expert Tristram Sainsbury (of the Australian Lowy Institute) says: “if the G20 did not exist, we would have to invent it”. With so many global problems requiring coordinated collective policy responses or new global standard-setting, not even big countries can go at it alone. At the same time, it is in the G20’s own interest to find constructive channels of engagement with non-G20 countries, some of whom are at the vanguard of policy innovation, implementing first what later often becomes mainstream in the rest of the world.

After the successful G20 summit in Hangzhou, we already start looking forward to the German presidency of the G20 in 2017. We would expect Germany to further advance the G20 attention for structural policies, including on topics like the digital economy, health care and responsible business conduct in global value chains. Undoubtedly, the OECD Secretariat will again provide the presidency useful analytical support. Wir werden bald sehen!

Useful links

OECD to help put innovation at heart of G20 global growth strategy

Ryan Parmentier, OECD Environment Directorate

Ryan Parmentier, OECD Environment Directorate

Imagine you have an important decision to make. Do you carefully consider the long-term implications of each possible option or do you act impulsively? Would you approach the decision-making process differently if the consequences stretched out to 30 or even 50 years?

Urban, spatial and land use planning professionals repeatedly find themselves in this predicament. There are significant and long-lasting economic as well as environmental impacts of the decisions that are made with respect to transportation, energy, waste, water, buildings and infrastructure. Yet, many land-use interventions do not properly account for environmental consequences. The decisions made regarding where and when roads are built, and the density, type and location of buildings all have long-term impacts on air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity and water use. Even seemingly indirect or unrelated decisions on the taxation of property can have a significant impact on environmental outcomes. As a result, the innumerable decisions related to land use – both big and small – need to be made so that growth is green.

This is an easy thing to say, but an increasingly challenging thing to do in a world that is changing incredibly fast. As a recent article on urban planning in the Economist pointed out, the city of London took 2000 years to grow from 30,000 to almost 10 million people. Cities in China are achieving the same growth rate in just 30 years! The pressures to deliver the services required by an expanding global population are challenging and the long-term environmental consequences are becoming impossible to ignore.

The 2016 OECD Green Growth and Sustainable Development Forum will tackle these very issues under the theme of “Urban green growth, spatial planning and land use”. An engaging agenda is being developed that will explore, through examples, whether existing land-use policies support green growth. The Forum will discuss the challenge of urban sprawl and the associated social and environmental consequences. It will examine the green growth challenges at the city level, giving consideration to innovative approaches and best practices. Issues related to resilient infrastructure, tracking and measuring progress on green growth as well as the role that finance and tax policies can have on land use outcomes will also be discussed. One session will focus on the OECD’s Inclusive Growth in Cities Campaign and discuss how to build cities that are both inclusive and environmentally sustainable.

The Forum will consider green growth at all relevant levels, i.e. from both the national and sub-national perspectives and part of the broader international agenda. The latter includes the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement on climate change, Habitat III (the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development – Quito, Ecuador 17-20 October, 2016) and the 2017 Annual Green Growth Knowledge Platform Conference on resilient infrastructure that will be hosted by the World Bank.

The wide-ranging issues related to land use and the broader international agenda clearly demonstrate that to be successful, co-operation is crucial. This includes co-operation across local, regional and national levels to effectively green urban and spatial planning as well as land-use policies and decisions. Enhanced international co-operation is becoming urgent. This is particularly relevant in a world that is facing increasing uncertainty. There will be growing pressure and a natural instinct to continue to make decisions that benefit the short term when the future is uncertain. But now more than ever, we need to work together to make sure that does not happen.

Useful links

The 2016 OECD Green Growth and Sustainable Development (GGSD) Forum: Urban Green Growth, Spatial Planning and Land Use Paris, 9-10 November

“Cities and Green Growth: A Conceptual Framework”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers 2011/08