Cryptology: the art and science of keeping words secure

As a cryptologist (alternatively cryptographer), what greater important responsibility could I possibly bear than that of keeping words secure? Cryptology is sometimes defined as the art of writing and solving codes. I am going to contest that on a number of fronts, not the least being that cryptology is far more important to all of us than that definition suggests.

Codes and ciphers

The word code comes with one major ambiguity. Most definitions agree that a code represents a system for representing symbols (often in the form of letters) by other symbols. It is often assumed that this must be for providing secrecy. However there are many good reasons why we use codes for purposes other than keeping secrets. Arguably the most famous code of all, Morse code, was invented in order to transfer messages over a communication channel that could only transmit pulses of electronic current. There is nothing secret about this. Indeed the whole point is that anyone with access to these pulses can recover the words that they represent.

The term cipher is often used as a synonym for code, but is consistently associated with codes that provide secrecy. Good practice in design of ciphers dictates that the general technique for enciphering should be understood by everyone, including those from whom we are trying to hide our words. This requires that the genuine users of the cipher know a secret that is unknown to everyone else.

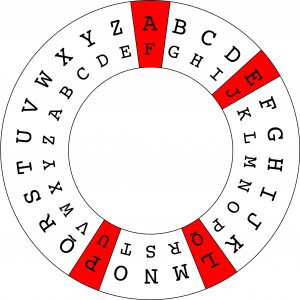

A simple example may clarify this. The classical Shift cipher enciphers a letter by replacing it with the letter a predetermined number of positions ahead of it in the alphabet. Many people know that this is how the Shift cipher works in principle, but to actually decipher a secret message you need to know a secret, which in this case is the agreed shift length. Hence the message APPLE is converted to FUUQJ under a secret shift of 5.

Just to confuse things, the word cipher is not only used as above to describe the overall system, but sometimes also used to describe the secret, and occasionally even the enciphered message itself. That is why cryptologists tend to avoid the word cipher and refer to these three separate concepts as the cryptosystem, key, and ciphertext, respectively.

Much more than secrecy

Up until the mass adoption of computers and digital networks, cryptology was an art practiced mainly in the military and intelligence domains. From the application of Mary Queen of Scots’ Babington cipher through to the Enigma, these are environments in which the need to keep certain information secret should be self-evident. Keeping words secure in this context is mainly about providing secrecy, which cryptologists tend to refer to as confidentiality.

Fast forwarding to today’s interconnected technological world, the need for confidentiality of certain types of data remains, but nowadays we have even greater concerns. Consider, for example, that most of our financial transactions speed around the globe on digital networks. While we may not be keen on others observing the details of our personal banking, what matters more is that the associated data is transferred correctly and between the right people. Cryptology provides the tools to address both of these problems through mechanisms for providing data integrity and authentication. These tools make sure that when our words arrive at their intended destination they may well be secret, but more importantly they are precisely as we formed them (spelling mistakes intact) and demonstrably from us.

Words to secure words

There is an irony which must now be highlighted.

Words, as combinations of letters, are not processed by computers directly. Instead they are first converted into binary, which is itself a code (not a cipher!) consisting of strings of ones and zeroes. Indeed the means of converting letters into binary is itself dictated by standardized codes (not ciphers) such as ASCII. Modern cryptographic mechanisms process binary, not letters, and the secret keys upon which these algorithms rely must also be represented in binary. This is fine if the key is stored on the chip of a bank card but there are occasions when we need to activate a cryptographic key on a computer, such as when we instruct file encryption software to protect a document of particularly treasured words.

Guess what? We are not too hot at remembering sequences of ones and zeroes of the length required by modern cryptosystems. A related version of the same problem occurs when we log on to a digital system and are asked to provide evidence that we are who we claim to be. So what do we tend to use as a proxy for cryptographic keys? Words, of course, in the form of passwords.

Cryptology may well be responsible for garbling beautiful words into unintelligible nonsense, but words are also responsible for making cryptology work for all of us.

The opinions and other information contained in OxfordWords blog posts and comments do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Oxford University Press.

Next post: What are the origins of lord and lady?

Next post: What are the origins of lord and lady?  Previous Post: Quiz: which Hunger Games character are you?

Previous Post: Quiz: which Hunger Games character are you?

Comments