From Our Daily Report

-

There is common political content to all the relentless terror attacks—whether they come from the Islamist right or Islamophobie right, they are equally part of the global reaction.

-

Hackers linked to Russian state intelligence used WikiLeaks to throw the US election, so Trump and Putin can instate a fascist order worldwide. Yes, we're serious.

-

Civilian casualties have reached a record high in the first half of 2016, with 5,166 civilians recorded killed or maimed, the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan reports.

-

At least 48 Palestinian prisoners now participating in an open-ended hunger strike in protest of Israel's policy of detention without charge or trial.

DEFEAT PENDEJO-FASCISM!

Bernie is OK — but not 'or Bust'

by Bill Weinberg, The Villager

A few weeks ago, I wrote about a protest by members of New York's Peruvian immigrant community in Union Square, to oppose the candidacy of Keiko Fujimori in the South American country's presidential race—the daughter of imprisoned ex-dictator Alberto Fujimori, who intransigently defends her father's blood-drenched legacy. Peru's left mobilized for her defeat.

Keiko was opposed by a merely odious center-right technocrat and former cabinet minister, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, or "PPK." Verónika Mendoza, the left-wing candidate who was bumped out of the race in the first round in April, urged her supporters to vote for pro-corporate conservative PPK, so as to keep openly fascistic Keiko out of office—and to be prepared to build a vigorous opposition from his first day on the job.

It was a very close vote, but it worked—PPK won by the proverbial hair in the June 5 run-off.

As if to drive home the point that PPK is merely a lesser enemy (but still very much an enemy), soon after his election he unveiled an economic program that calls for privatization of Peru's communal indigenous and peasant lands—and their sale to mining, oil and agribusiness interests. Land-grabs by corporate interests have already been a source of much rural unrest in Peru in recent years.

I hope the analogy is clear.

OAXACA TEACHERS MOVEMENT

Not Thwarted by State Terror

by Shirin Hess, Waging Nonviolence

On June 19, the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca was the scene of a senseless massacre. The bloody battle took place in the rural town of Nochixtlan and resulted in the death of at least nine civilians. "Right now, the federal police are withdrawing, going back to their vehicles," said a witness of the attack as he filmed the horrific scene. Bullets are heard smashing against metal traffic barriers on the roadside as the camera image shakes. Taking heavy breaths he calmly continued, "And as they retreat, they are shooting at us with firearms."

A week earlier, police crackdowns had begun in various regions of Oaxaca state. These acts of violence are occurring in light of current protests in Oaxaca, where—since May 15—the teachers’ movement has set up a peaceful plantón, or encampment, in the city center, and dozens of roadblocks across the state, including Nochixtlan. The teachers demanded a dialogue with the local and federal government about a recently approved education overhaul and the implementation of its neoliberal policies in Oaxaca.

DEMOCRACY GODDESS COMES TO CHINATOWN

by Bill Weinberg, The Villager

The "Goddess of Democracy" became a global icon when she was raised by student protesters in Beijing's Tiananmen Square in 1989—before the movement was put down in the massacre of June 4. In the prelude to this year's anniversary of the massacre, the Democracy Goddess came to Manhattan's Chinatown. While the original raised in Beijing 27 years ago was of papier-maché and stood some 30 feet, this one was of fiberglass and about 10 feet high. It was raised in Confucius Plaza on May 30, right in front of the statue of the revered philosopher, at the corner of Bowery and Division.

Owing much to New York’s Statue of Liberty but also to the French Marianne, the Goddess stands holding a torch aloft. Across the statue's breast is a banner with the words "Freedom is not free."

Standing below are her creator, California-based artist Chen Weiming, and his small entourage. They have just arrived in the city following a cross-country tour with the Goddess.

WHY MINING CORPORATIONS LOVE TRADE DEALS

by Ben Beachy, Huffington Post

From the salmon-spawning waters of Alaska to the cloud forests of Ecuador, communities are standing up to mining projects that threaten their health, environment, and livelihoods.

But mining corporations are fighting back with a powerful tool buried in trade and investment agreements: the ability to go to private, unaccountable tribunals and sue governments that act to protect communities from mining.

In these private tribunals, which sit outside of any domestic legal system, corporate lawyers—not judges—decide whether governments must pay corporations for halting destructive mining projects. To date, mining corporations have used these private tribunals to sue over 40 governments more than 100 times.

In two-thirds of the concluded cases, governments either have been ordered to pay the mining corporations or have settled with them, which can require handing over payment and/or weakening mining restrictions. In the 44 publicly available mining cases still pending, mining corporations are demanding over $53 billion from governments.

EL NIÑO & ETHIOPIA'S THREATENED PASTORALISTS

by James Jeffrey, IRIN

BORAMA — Sitting on parched ground pummelled by the sun, a camel looks on majestically as pastoralists mill around it in a whirl of activity. Loaded onto its back are sacks of grains and pulses, yellow jerry cans, bottles of cooking oil, bits of fabric and plastic to make rough bivouac structures, and more.

After a final check of ropes, a woman makes a loud purring noise while gesturing upwards. The camel jerkily stands up, emitting a loud groan. Leading it by a rope, the family rejoins other pastoralists trekking through the Awdal Region abutting Somaliland's northwestern border with Ethiopia: home for those on the move.

Faced with desiccated pastures in Ethiopia's Somali Region last November, these pastoralists and many others responded to rumors of rains and good pasture hundreds of kilometers away on the coast of Somaliland, an internationally unrecognized but de facto sovereign nation separate from Somalia.

But, when they got there, there wasn't enough rain or pasture for the numbers that descended. Thousands of goats, sheep, cows, and even drought-hardy camels died, buried in mass graves to prevent disease spreading. (It still broke out, killing further livestock). Now, the pastoralists are returning to Ethiopia, or trying to do so.

CHIBOK GIRLS — DO WE REALLY CARE?

#BringBackOurGirls should be more than a hashtag

by Hilary Matfess, IRIN

MAIDUGURI — The world united in a campaign to demand #BringBackOurGirls after the abduction of the Chibok school girls two years ago by the Nigerian jihadist group Boko Haram. But there has been next to nothing in the way of support to the women that have managed to escape the militants.

They are now homeless, reduced to begging to survive, and forced to deal alone with the trauma of their ordeal.

Safiya sits on a woven mat under a scraggly tree in the grounds of Madina Mosque, on the outskirts of the northeastern city of Maiduguri, rocking her newborn son. The mosque has become a rough-and-ready sanctuary for around 2,000 people who have fled the conflict.

"We spent three months in the forest, crawling through the bush, bringing all five children and trying not to disturb the infection in my husband's wound from where Boko Haram shot him," she says.

She was pregnant as well at the time. When she felt the baby was almost due, she left her husband with the children and walked the remaining 70 kilometres to Maiduguri, and this mosque.

Safiya delivered her son here a week later, without a doctor, midwife, or medicine. Her family finally managed to join her, helped by communities along their path, and though they are now physically safe and united, that's about the extent of it.

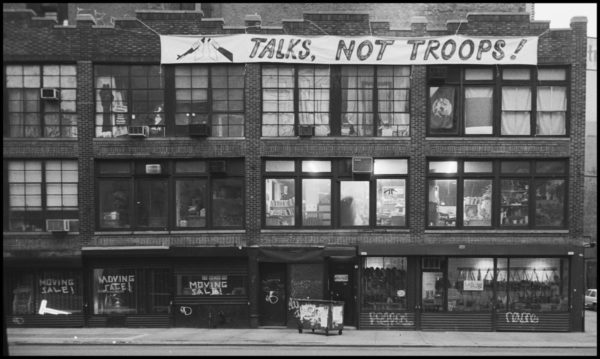

ADIEU TO THE 'PEACE PENTAGON'

by Bill Weinberg, The Villager

The night of Thursday May 5 was a bittersweet one for me. For probably the last time in my life, I crossed the threshold of 339 Lafayette St., for a "Moving the Movement" farewell party. I was bidding adieu to the building that three generations of activists had affectionately called the "Peace Pentagon." The gathering was confined to one room of the three-story structure, with construction tape barring access to the other rooms, and the halls deserted. It was an eerie feeling.

The first time I entered the building at the corner of Lafayette and Bleecker, I was in my senior year of high school. It was 1980, Reagan's election was imminent, the Iran hostage crisis and Soviet invasion of Afghanistan dominated the headlines, and the big lurch to the right was in frightening progress. President Carter, who had been elected on a pledge to pardon Vietnam-era draft resisters, capitulated to the new bellicose zeitgeist by bringing back draft registration. I was in the first crop of 18-year-olds to have to register with the Selective Service System since 1973. This precipitated my first activist involvement—a student anti-draft group. Through this, I was inevitably drawn into the orbit of the War Resisters League—the venerable pacifist organization that grew out of anti-draft efforts in World War I, and was the anchor tenant at 339.

CHALLENGING THE NATION STATE IN SYRIA

by Leila Al Shami, Fifth Estate

Syria's current borders were drawn up by imperial map-makers a hundred years ago in the midst of World War I as part of a secret accord between France and Britain to divide the Mideast spoils of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. As the colonial state gave way to the post-independence state, power was transferred from Western masters to local elites.

The three major discourses which grew out of the anti-colonial struggle—socialism, Arab nationalism, and Islamism—all fetishized the idea of a strong state as the basis of resistance to Western hegemony. In the case of Syria, it led to the emergence of an ultra-authoritarian regime where power is centralized around one man in Damascus, Bashar al-Assad, bolstered by the state bureaucracy, and security forces. But today, new ways of organizing have emerged which challenge centralized authority and the state framework.

During the course of the revolution against Assad that began in Syria in 2011, land was liberated to the extent that by 2013 the regime had lost control over some four-fifths of the country. As the state began to disintegrate, communities needed to build alternative structures to keep life functioning in the newly created autonomous zones.

Recent Updates

11 hours 49 min ago

18 hours 46 min ago

20 hours 12 min ago

20 hours 18 min ago

1 day 18 hours ago

1 day 18 hours ago

3 days 15 hours ago

3 days 16 hours ago

3 days 16 hours ago

5 days 8 hours ago