- published: 23 Apr 2016

- views: 20605

-

remove the playlistChris Hoffman

-

remove the playlistLongest Videos

- remove the playlistChris Hoffman

- remove the playlistLongest Videos

- published: 20 Apr 2016

- views: 3517

- published: 24 Apr 2016

- views: 8798

- published: 17 Oct 2014

- views: 1139

- published: 25 Apr 2014

- views: 731

- published: 03 May 2016

- views: 112

Chris

Chris is a short form of various names including Christopher, Christian, Christina, Christine, and Christos. Unlike these names, however, it does not indicate the person's gender although it is much more common for males to have this name than it is for females.

It is the preferred form of the full name of such notable individuals as Chris Tucker and Chris Penn. To find an article about one of these people, see List of all pages beginning with "Chris".

The word is also part of phrases, including Tropical Storm Chris, Ruth's Chris Steak House, and many more which refer to notable people, places, and things. For a list of these, see All pages with titles containing chris.

People with the given name

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

Hoffman

Hoffmann or Hofmann is a surname of German origin. The original meaning in medieval times was "steward, i.e. one who manages the property of another". The name was later adopted by many Jewish families. In English and other European languages, including Yiddish and Dutch, the name is also spelt Hoffman, Hofman, Huffman, Gofman or Hofmans.

Hoffman

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

- Loading...

-

6:19

6:19Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 2 Full Fight Vid

Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 2 Full Fight VidPilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 2 Full Fight Vid

Chris Hoffman and Caloy Baduria continue their slugfest on round two. That's all I am going to share! It's bad enough that I was rooting for Caloy and that he lost because he got injured. Overall, amazing fight between these two great legends of URCC! -

7:32

7:32Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 1 Full Fight Video

Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 1 Full Fight Video -

3:18

3:18URCC 27 Rebellion: CHRIS HOFFMAN vs. CALOY BADURIA PRIMER

URCC 27 Rebellion: CHRIS HOFFMAN vs. CALOY BADURIA PRIMERURCC 27 Rebellion: CHRIS HOFFMAN vs. CALOY BADURIA PRIMER

See the preparation of Chris Hoffman and Caloy Baduria before their much-awaited fight. Subscribe to ABS-CBN Sports And Action channel! - http://bit.ly/ABSCBNSports Visit our website at http://sports.abs-cbn.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABSCBNSports Twitter: https://twitter.com/abscbnsports Instagram: https://instagram.com/abs_cbnsports -

1:43

1:43URCC 27: Chris Hoffman vs Caloy Baduria

URCC 27: Chris Hoffman vs Caloy BaduriaURCC 27: Chris Hoffman vs Caloy Baduria

URCC 27: Chris Hoffman vs Caloy Baduria Fight Highlights - April 23, 2016 Subscribe to ABS-CBN Sports And Action channel! - http://bit.ly/ABSCBNSports Visit our website at http://sports.abs-cbn.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABSCBNSports Twitter: https://twitter.com/abscbnsports Instagram: https://instagram.com/abs_cbnsports -

9:09

9:09Chris Hoffman VS. Brandon Horton

Chris Hoffman VS. Brandon Horton -

0:52

0:52URCC 25 TAKEOVER: CHRIS HOFFMAN (DEFTAC)

URCC 25 TAKEOVER: CHRIS HOFFMAN (DEFTAC)URCC 25 TAKEOVER: CHRIS HOFFMAN (DEFTAC)

FIGHT TEASER undefeated in bjj comps and amateur mma, this standout wants to show everybody that he is a force to be reckoned with in the URCC. He will be going up against an equally undefeated opponent in the guise of Philippine Volcanoes Nikson Kola, a native of Papua New Guinea. Watch him fight LIVE at the URCC Takeover on October 23, 2014 at the MOA Arena! Get your tickets NOW fight fans! Only 6 days left till fight night! Bakbakan na! -

1:10

1:10URCC 27 Caloy Baduria vs Chris Hoffman Weigh-in

URCC 27 Caloy Baduria vs Chris Hoffman Weigh-inURCC 27 Caloy Baduria vs Chris Hoffman Weigh-in

-

5:17

5:17Madmen april 2014 James Mcnamara vs Chris Hoffman

Madmen april 2014 James Mcnamara vs Chris HoffmanMadmen april 2014 James Mcnamara vs Chris Hoffman

"Madmen" april 2014 James Mcnamara vs Chris Hoffman #liveinthecage Amateur Combat Sports Live Also Known as www.ACSLIVE.TV has jumped ahead of the game and started a Sports Network of their own. Live Fighting and FREE FIGHT VIDEOs in the cage or maybe some cool sounds from your favorite local band I've seen them cover it all.Live Mixed Martial Arts , despite what many might think, Live Mixed Martial Arts is well known across hundreds of nations all over the world. Live Mixed Martial Arts has been around for several centuries and has a very important meaning in the lives of many. It would be safe to assume that Live Mixed Martial Arts is going to be around for a long time and have an enormous impact on the lives of many people. FREE FIGHT VIDEOs,free fighting,free mma video's ,free cage fighting video,Facebook https://www.facebook.com/Acslivetv Youtube http://www.youtube.com/user/Keystrokeguru website www.amateurcombatsportslive.com -

3:55

3:55Chris Hoffman Creep

Chris Hoffman Creep -

![LABtrio, Michaël Attias, Chris Hoffman - Low Fat [JAZZ TODAY!]; updated 03 May 2016; published 03 May 2016](http://web.archive.org./web/20160712230833im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/AiUFOSLsa4I/0.jpg) 4:31

4:31LABtrio, Michaël Attias, Chris Hoffman - Low Fat [JAZZ TODAY!]

LABtrio, Michaël Attias, Chris Hoffman - Low Fat [JAZZ TODAY!]LABtrio, Michaël Attias, Chris Hoffman - Low Fat [JAZZ TODAY!]

A meticulous selection of the best artists that make JAZZ TODAY ! With Dj Cam Quartet, Ben Sidran, Anne Paceo... ✔ Listen to the full playlist : http://bit.ly/1rR1GhK ✔ Follow us on Spotify: http://bit.ly/23dLyE7 / Deezer: http://bit.ly/23dLEvD ✔ Subscribe to Jazz Everyday → http://bit.ly/1Ydc0dN ↓TRACKLIST↓ 1 Cap de bonne espérance - Florian Pellissier Quintet 2 Dakota Mab - Henri Texier 3 Blue Sunday - Luca Aquino 4 Yggdrasil - PJ5 5 Low Fat - LABTrio 6 Diner Flottant - Perrine Mansuy 7 Angel Heart (The Session Version) - Dj Cam Quartet 8 Moons - Anne Paceo 9 Lennon - Dino Rubino 10 aKa 466 (After the Sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti)Aka Moon Fabian Fiorini 11 Sicilienne - Pierre de Bethmann Trio 12 Jeju-Do Rémi Panossian Trio 13 The Whistleblowers - David Linx, Paolo Fresu, Diederik Wissels 14 Calm Down - Leron Thomas 15 Si tu vois ma mère - David Krakauer Production: | My Favorite Things

'Chris Hoffman' is featured as a movie character in the following productions:

Ignition Buzz TV Countdown (2003)

Actors: Andy Samberg (actor), Akiva Schaffer (actor), Jorma Taccone (actor), Andy Samberg (producer), Akiva Schaffer (producer), Jorma Taccone (producer), Andy Samberg (writer), Andy Samberg (writer), Akiva Schaffer (writer), Akiva Schaffer (writer), Jorma Taccone (writer), Jorma Taccone (writer), Jorma Taccone (composer), Akiva Schaffer (director), Akiva Schaffer (editor),

Genres: Comedy, Short,Hoffman, Chris Filmography

-

2009, role: actor , character name: Gus

-

2007, role: actor , character name: Bully Dog

-

2004, role: actor , character name: Office Dork

-

2004, role: actor , character name: Steve

-

2003, role: actor , character name: Watcher

-

2002, role: actor , character name: Detective Kecker

-

2000, role: actor , character name: Dennis Hobbs

-

1999, role: actor , character name: Louis

-

1999, role: actor

-

1998, role: actor

-

1992, role: actor , character name: Wiseone

-

1992, role: actor , character name: Surfer

-

1992, role: actor , character name: Tango Dancer

-

1992, role: actor , character name: Note

-

1991, role: actor

-

1989, role: actor , character name: Narrator

-

1987, role: actor

-

1985, role: actor

Hoffman, Chris Filmography

-

2013, role: miscellaneous crew

Hoffman, Chris Filmography

-

2003, role: miscellaneous crew

-

Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 2 Full Fight Vid

Chris Hoffman and Caloy Baduria continue their slugfest on round two. That's all I am going to share! It's bad enough that I was rooting for Caloy and that he lost because he got injured. Overall, amazing fight between these two great legends of URCC! -

-

URCC 27 Rebellion: CHRIS HOFFMAN vs. CALOY BADURIA PRIMER

See the preparation of Chris Hoffman and Caloy Baduria before their much-awaited fight. Subscribe to ABS-CBN Sports And Action channel! - http://bit.ly/ABSCBNSports Visit our website at http://sports.abs-cbn.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABSCBNSports Twitter: https://twitter.com/abscbnsports Instagram: https://instagram.com/abs_cbnsports -

URCC 27: Chris Hoffman vs Caloy Baduria

URCC 27: Chris Hoffman vs Caloy Baduria Fight Highlights - April 23, 2016 Subscribe to ABS-CBN Sports And Action channel! - http://bit.ly/ABSCBNSports Visit our website at http://sports.abs-cbn.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABSCBNSports Twitter: https://twitter.com/abscbnsports Instagram: https://instagram.com/abs_cbnsports -

-

URCC 25 TAKEOVER: CHRIS HOFFMAN (DEFTAC)

FIGHT TEASER undefeated in bjj comps and amateur mma, this standout wants to show everybody that he is a force to be reckoned with in the URCC. He will be going up against an equally undefeated opponent in the guise of Philippine Volcanoes Nikson Kola, a native of Papua New Guinea. Watch him fight LIVE at the URCC Takeover on October 23, 2014 at the MOA Arena! Get your tickets NOW fight fans! Only 6 days left till fight night! Bakbakan na! -

URCC 27 Caloy Baduria vs Chris Hoffman Weigh-in

-

Madmen april 2014 James Mcnamara vs Chris Hoffman

"Madmen" april 2014 James Mcnamara vs Chris Hoffman #liveinthecage Amateur Combat Sports Live Also Known as www.ACSLIVE.TV has jumped ahead of the game and started a Sports Network of their own. Live Fighting and FREE FIGHT VIDEOs in the cage or maybe some cool sounds from your favorite local band I've seen them cover it all.Live Mixed Martial Arts , despite what many might think, Live Mixed Martial Arts is well known across hundreds of nations all over the world. Live Mixed Martial Arts has been around for several centuries and has a very important meaning in the lives of many. It would be safe to assume that Live Mixed Martial Arts is going to be around for a long time and have an enormous impact on the lives of many people. FREE FIGHT VIDEOs,free fighting,free mma video's ,free cag... -

-

LABtrio, Michaël Attias, Chris Hoffman - Low Fat [JAZZ TODAY!]

A meticulous selection of the best artists that make JAZZ TODAY ! With Dj Cam Quartet, Ben Sidran, Anne Paceo... ✔ Listen to the full playlist : http://bit.ly/1rR1GhK ✔ Follow us on Spotify: http://bit.ly/23dLyE7 / Deezer: http://bit.ly/23dLEvD ✔ Subscribe to Jazz Everyday → http://bit.ly/1Ydc0dN ↓TRACKLIST↓ 1 Cap de bonne espérance - Florian Pellissier Quintet 2 Dakota Mab - Henri Texier 3 Blue Sunday - Luca Aquino 4 Yggdrasil - PJ5 5 Low Fat - LABTrio 6 Diner Flottant - Perrine Mansuy 7 Angel Heart (The Session Version) - Dj Cam Quartet 8 Moons - Anne Paceo 9 Lennon - Dino Rubino 10 aKa 466 (After the Sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti)Aka Moon Fabian Fiorini 11 Sicilienne - Pierre de Bethmann Trio 12 Jeju-Do Rémi Panossian Trio 13 The Whistleblowers - David Linx, Paolo Fresu, Diederik Wisse...

Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 2 Full Fight Vid

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:19

- Updated: 23 Apr 2016

- views: 20605

Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 1 Full Fight Video

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:32

- Updated: 23 Apr 2016

- views: 11824

URCC 27 Rebellion: CHRIS HOFFMAN vs. CALOY BADURIA PRIMER

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:18

- Updated: 20 Apr 2016

- views: 3517

- published: 20 Apr 2016

- views: 3517

URCC 27: Chris Hoffman vs Caloy Baduria

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:43

- Updated: 24 Apr 2016

- views: 8798

- published: 24 Apr 2016

- views: 8798

Chris Hoffman VS. Brandon Horton

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:09

- Updated: 23 Dec 2011

- views: 1108

URCC 25 TAKEOVER: CHRIS HOFFMAN (DEFTAC)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:52

- Updated: 17 Oct 2014

- views: 1139

- published: 17 Oct 2014

- views: 1139

URCC 27 Caloy Baduria vs Chris Hoffman Weigh-in

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:10

- Updated: 22 Apr 2016

- views: 435

- published: 22 Apr 2016

- views: 435

Madmen april 2014 James Mcnamara vs Chris Hoffman

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:17

- Updated: 25 Apr 2014

- views: 731

- published: 25 Apr 2014

- views: 731

Chris Hoffman Creep

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:55

- Updated: 08 Jan 2015

- views: 99

LABtrio, Michaël Attias, Chris Hoffman - Low Fat [JAZZ TODAY!]

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:31

- Updated: 03 May 2016

- views: 112

- published: 03 May 2016

- views: 112

-

Chris and Catherine Hoffman Wedding 2016

March 5th, 2016 @ Radisson Hotel Beachside - Indian Harbor Beach, FL -

Juan Pablo Carletti / Tony Malaby / Christopher Hoffman - In Gardens - Arts For Art - Sep 20 2014

Juan Pablo Carletti - drums, compositions Tony Malaby - tenor saxophone Christopher Hoffman - cello http://www.artsforart.org/support.html -

Dr Chris Hoffman: Cotrimoxazole as Preventive Therapy, Sept 2010

-

RIT TownHall - Sept 2015 (4 of 4) - Research Data Management - Chris Hoffman

Chris Hoffman, Manager of Informatics Services in UC Berkeley's Research IT group, gives an overview of the newly-launched Research Data Management program at a Town Hall meeting of 24 Sept 2015. -

Flyers vs. Dryden --Chris Hoffman.mov

-

TFN Opening - Chief Bryce Williams, Kenneth D'Sena and Chris Hoffman

Chief Bryce WIlliams starts the event with an opening prayer, followed by introductions and opening remarks by Envision Financial's Kenneth D'Sena. TFN Economic Development Corporation's Chris Hoffman delivers an economic development overview. -

-

CIA Bitcoin CONSPIRACY, SILVER TO BREAK THE ECONOMY - Andy Hoffman & Chris Duane

IN THIS INTERVIEW: *Bitcoin Price Surpasses Gold (0:51) *CIA Involved in Bitcoin (9:15) *Silver Will Break the Financial System (14:42) *Federal Reserve Has NO CHOICE Than To Print Money (21:12) ANDY HOFFMAN: http://MilesFranklin.com & http://bit.ly/AndyHoffmanBlog CHRIS DUANE: http://Dont-Tread-On.me & http://youtube.com/TruthNeverTold LIBERTY MASTERMIND SYMPOSIUM: Join Elijah Johnson, Andy Hoffman, Chris Duane along with 12 more of the most influential thought leaders in the world of alternative media at the Liberty Mastermind Symposium in Las Vegas Feb. 21-22, 2014. Register today at: http://LibertyMastermind.us FINANCE AND LIBERTY: SUBSCRIBE (It's FREE!) to "Finance and Liberty" for more interviews and financial insight: http://bit.ly/Subscription-Link Website: http://FinanceAndLibe... -

Panel: Quantum Theory and Free Will - Chris Fields, Henry Stapp & Donald Hoffman

Quantum theory incorporates two seemingly-contradictory ideas about free will. On the one hand, an observer can choose both the system to measure and the kind of measurement to make; given these choices, the theory predicts a probability distribution over the possible outcomes and nothing more. is is "quantum indeterminism." On the other hand, a system that no one is looking at evolves through time according the dynamics that are perfectly deterministic. No one is "looking at" the universe as a whole - all observers are inside the universe by definition - so the time evolution of the whole universe must be perfectly deterministic. This clash between indeterminism and determinism is sharpened by the existence of a strong theorem, the Conway-Kochen "free will theorem," that says that if hu... -

Chris and Catherine Hoffman Wedding 2016

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 118:52

- Updated: 27 Mar 2016

- views: 50

- published: 27 Mar 2016

- views: 50

Juan Pablo Carletti / Tony Malaby / Christopher Hoffman - In Gardens - Arts For Art - Sep 20 2014

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 35:27

- Updated: 24 Sep 2014

- views: 1464

- published: 24 Sep 2014

- views: 1464

Dr Chris Hoffman: Cotrimoxazole as Preventive Therapy, Sept 2010

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 41:31

- Updated: 10 Jul 2012

- views: 752

- published: 10 Jul 2012

- views: 752

RIT TownHall - Sept 2015 (4 of 4) - Research Data Management - Chris Hoffman

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 30:26

- Updated: 29 Sep 2015

- views: 60

- published: 29 Sep 2015

- views: 60

Flyers vs. Dryden --Chris Hoffman.mov

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 139:21

- Updated: 18 Apr 2012

- views: 45

- published: 18 Apr 2012

- views: 45

TFN Opening - Chief Bryce Williams, Kenneth D'Sena and Chris Hoffman

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 26:30

- Updated: 17 Oct 2014

- views: 71

- published: 17 Oct 2014

- views: 71

Hand-Eye Supply Curiosity Club presents Chris Hoffman of Ryn

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 41:01

- Updated: 13 Feb 2013

- views: 35

CIA Bitcoin CONSPIRACY, SILVER TO BREAK THE ECONOMY - Andy Hoffman & Chris Duane

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 31:09

- Updated: 03 Dec 2013

- views: 37600

- published: 03 Dec 2013

- views: 37600

Panel: Quantum Theory and Free Will - Chris Fields, Henry Stapp & Donald Hoffman

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 65:07

- Updated: 18 Nov 2014

- views: 26476

- published: 18 Nov 2014

- views: 26476

Jonah and Chris Baptism

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 62:36

- Updated: 28 Jun 2016

- views: 21

- Playlist

- Chat

- Playlist

- Chat

Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 2 Full Fight Vid

- Report rights infringement

- published: 23 Apr 2016

- views: 20605

Pilipinas MMA's live URCC27 Chris Hoffman vs. Caloy Baduria Round 1 Full Fight Video

- Report rights infringement

- published: 23 Apr 2016

- views: 11824

URCC 27 Rebellion: CHRIS HOFFMAN vs. CALOY BADURIA PRIMER

- Report rights infringement

- published: 20 Apr 2016

- views: 3517

URCC 27: Chris Hoffman vs Caloy Baduria

- Report rights infringement

- published: 24 Apr 2016

- views: 8798

Chris Hoffman VS. Brandon Horton

- Report rights infringement

- published: 23 Dec 2011

- views: 1108

URCC 25 TAKEOVER: CHRIS HOFFMAN (DEFTAC)

- Report rights infringement

- published: 17 Oct 2014

- views: 1139

URCC 27 Caloy Baduria vs Chris Hoffman Weigh-in

- Report rights infringement

- published: 22 Apr 2016

- views: 435

Madmen april 2014 James Mcnamara vs Chris Hoffman

- Report rights infringement

- published: 25 Apr 2014

- views: 731

Chris Hoffman Creep

- Report rights infringement

- published: 08 Jan 2015

- views: 99

LABtrio, Michaël Attias, Chris Hoffman - Low Fat [JAZZ TODAY!]

- Report rights infringement

- published: 03 May 2016

- views: 112

- Playlist

- Chat

Chris and Catherine Hoffman Wedding 2016

- Report rights infringement

- published: 27 Mar 2016

- views: 50

Juan Pablo Carletti / Tony Malaby / Christopher Hoffman - In Gardens - Arts For Art - Sep 20 2014

- Report rights infringement

- published: 24 Sep 2014

- views: 1464

Dr Chris Hoffman: Cotrimoxazole as Preventive Therapy, Sept 2010

- Report rights infringement

- published: 10 Jul 2012

- views: 752

RIT TownHall - Sept 2015 (4 of 4) - Research Data Management - Chris Hoffman

- Report rights infringement

- published: 29 Sep 2015

- views: 60

Flyers vs. Dryden --Chris Hoffman.mov

- Report rights infringement

- published: 18 Apr 2012

- views: 45

TFN Opening - Chief Bryce Williams, Kenneth D'Sena and Chris Hoffman

- Report rights infringement

- published: 17 Oct 2014

- views: 71

Hand-Eye Supply Curiosity Club presents Chris Hoffman of Ryn

- Report rights infringement

- published: 13 Feb 2013

- views: 35

CIA Bitcoin CONSPIRACY, SILVER TO BREAK THE ECONOMY - Andy Hoffman & Chris Duane

- Report rights infringement

- published: 03 Dec 2013

- views: 37600

Panel: Quantum Theory and Free Will - Chris Fields, Henry Stapp & Donald Hoffman

- Report rights infringement

- published: 18 Nov 2014

- views: 26476

Jonah and Chris Baptism

- Report rights infringement

- published: 28 Jun 2016

- views: 21

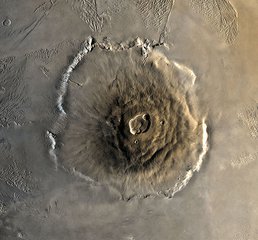

[VIDEO]: Stunning 'Hidden Morse Code Message' Found On Martian Surface

Edit WorldNews.com 12 Jul 201616-Year Veteran Firefighter Unemployed After Black Lives Matter Racist Facebook Posts

Edit WorldNews.com 12 Jul 2016Summer Of Chaos In U.S. Mirrors The End Of Power

Edit WorldNews.com 12 Jul 2016Up, Up and Away! Child Nearly Abducted By Eagle At Australian Wildlife Show

Edit WorldNews.com 12 Jul 2016Philippines wins South China Sea case against China

Edit The Irish Times 12 Jul 2016OPP DNA sweep 'overly broad': Report

Edit Toronto Sun 13 Jul 2016How this one hole could change the outcome of the British Open

Edit New York Post 13 Jul 2016Argonauts hope to take advantage at home vs. Redblacks

Edit Toronto Sun 13 Jul 2016RealNetworks Appoints Chris Jones to Board of Directors

Edit PR Newswire 12 Jul 2016TV News Roundup: Chris Harrison Returns To Host ‘Miss America,’ Netflix Sets Premiere Date for ‘Fearless’

Edit Variety 12 Jul 2016Chris Brown's Las Vegas Residency On Hold Following 'Racist' Allegations Against Drai's Nightclub

Edit Billboard 12 Jul 2016The Squeeze: Face to Face with Chris Harris Jr. (Denver Broncos)

Edit Public Technologies 12 Jul 2016Tuesday cover: Focus is on Chris Froome who targets third Tour de France title

Edit The National 12 Jul 2016qch chris and tina d'esposito goats

Edit Australian Broadcasting Corporation 12 Jul 2016Chris Sale: I quit chewing tobacco when Tony Gwynn died

Edit USA Today 12 Jul 2016AL All-Star starter Chris Sale ready to 'let it eat' for one inning

Edit Chicago Tribune 12 Jul 2016- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Next page »