- Loading...

-

Etruscan Art

Etruscan Art -

The Etruscan Origins of Rome and Italy

The Etruscan Origins of Rome and ItalyThe Etruscan Origins of Rome and Italy

A clip about the history of the Etruscans. Not much is known about them except for what has been found in the form of art, in burial sites and the occasional... -

Etruscan Art at the Louvre - L'Art Etrusque - L'arte degli Etruschi

Etruscan Art at the Louvre - L'Art Etrusque - L'arte degli EtruschiEtruscan Art at the Louvre - L'Art Etrusque - L'arte degli Etruschi

Etruscan Canopic Urn from Chiusi Canthare janiforme Sarcophagus of Cerveteri Couple 520BCE. -

Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part one)

Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part one)Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part one)

Aired on Channel Four (UK) in 2002 and co-produced by Gedeon Programmes; ARTE France; CNRS Images/Media; Le Musee De Louvre. -

M4 Etruscan Art

M4 Etruscan ArtM4 Etruscan Art

Made with Explain Everything -

Etruscans prt 1

Etruscans prt 1Etruscans prt 1

MORE: http://gekos.no/workshop/video.html The Etruscans, who lived in Etruria, were known as Tyrrhenians by the Greeks. They were at their height in Italy fr... -

Etruscan Women

Etruscan WomenEtruscan Women

Twenty-five hundred years ago, Etruscan women living in the Italian region of what is now called Tuscany were afforded a remarkably equal status with men. An... -

Arte Etrusca - Etruscan Art

Arte Etrusca - Etruscan ArtArte Etrusca - Etruscan Art

Gli alunni della classe clp13, 1P 2013/2014 del Liceo Enrico Fermi di Bologna, Vi riassumono il concetto di Arte Etrusca The students of the class clp13, 1P 2013/2014 of the high school Enrico Fermi of Bologna reassume the concept of Etruscan Art, enjoy !o) -

Italian Ancient Art Roman Greek Etruscan Traditions Italia Italy Old World Europe by BK Bazhe.com

Italian Ancient Art Roman Greek Etruscan Traditions Italia Italy Old World Europe by BK Bazhe.comItalian Ancient Art Roman Greek Etruscan Traditions Italia Italy Old World Europe by BK Bazhe.com

Italian Ancient Art - http://www.BAZHE.com Italian - Roman Art, Italia Italian Ancient Art is one of Europe's best, incorporating: the stunning Etruscan, Rom... -

The Etruscan, Greek and Roman Collections - Florence

The Etruscan, Greek and Roman Collections - FlorenceThe Etruscan, Greek and Roman Collections - Florence

The Archaeological Museum of Florence is situated in the heart of the city, in Palazzo della Crocetta, once the residence of Maria Maddalena de'Medici. Creat... -

Jewellery making gold glue solder for etruscan granulations, ancient goldsmiths enamel

Jewellery making gold glue solder for etruscan granulations, ancient goldsmiths enamelJewellery making gold glue solder for etruscan granulations, ancient goldsmiths enamel

Learn ancient goldsmiths art. Making antique reaction solder. In this video, I show my developed art with Chrysocolla stone from the Greek Chrysos (gold) and Kolla (glue) =gold glue (Goldleim) to soldering. The advantages are: high gloss after soldering, no polishing, high melting point and thus ideal for enameling Antique reaction soldering, so that the old Goldsmith's art will not be forgotten. More information on my Homepage www.Goldleim.de -

Funerary Art of the Etruscans

Funerary Art of the EtruscansFunerary Art of the Etruscans

Paul Denis, Associate Curator, World Cultures, Royal Ontario Museum, describes the cinerary chest (200 BC) and the practices of the Etruscans towards the dec... -

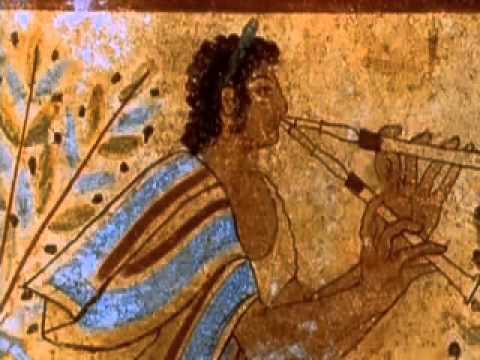

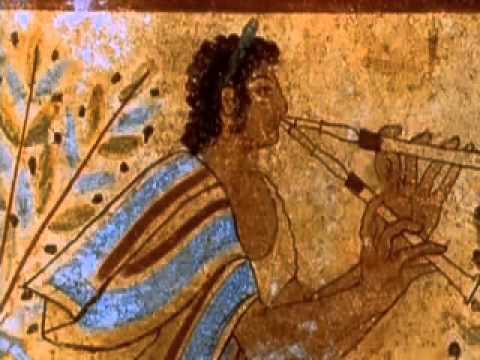

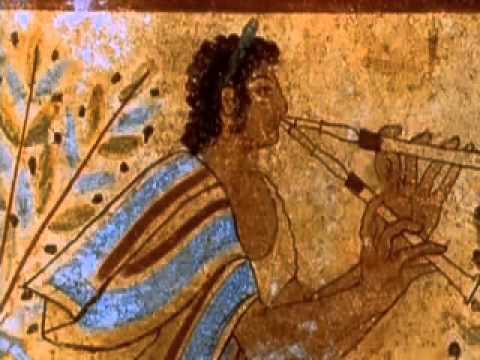

Etruscan Girl by "the NaYs"

Etruscan Girl by "the NaYs"Etruscan Girl by "the NaYs"

A young man falls in love with a picture of an Etruscan flute girl in his Art History book leading to a fanciful song about the imaginary relationship he cou... -

History of Art 5. Ancient Roman

History of Art 5. Ancient RomanHistory of Art 5. Ancient Roman

Ancient Roman. Fine Arts and Art History. Etruscan. Rome. Ókori Róma művészete. MUSIC: Arnold_Wohler - Adagio fur Orchester Colosseum KÉPJEGYZÉK: Etruscan, R...

- Ancient Egypt

- Ancient Greek art

- Apollo of Veii

- Art of Ancient Egypt

- Art of Mesopotamia

- Assyria

- Bronze Age

- Capitoline Museums

- Capitoline Wolf

- Category Pictish art

- Celtic art

- Central Italy

- Cerveteri

- Chiaroscuro

- Chimera of Arezzo

- Chiusi

- Corinth

- Etruscan art

- Etruscan religion

- Figurative art

- Fresco

- Funerary art

- Funerary cult

- Hellenistic

- Hellenistic art

- Ionia

- Iron Age

- Jōmon period

- Kroisos Kouros

- Metalworking

- Middle East

- Norchia

- Norse art

- Orvieto

- Phoenicia

- Populonia

- Portanaccio

- Roman art

- Sarcophagus

- Scythian art

- Situla (vessel)

- Tarquinia

- Veii

- Vetulonia

- Villanovan culture

- Visigothic art

- Vulca

- Vulci

- Walters Art Museum

-

Etruscan Art

Etruscan ArtEtruscan Art

-

The Etruscan Origins of Rome and Italy

The Etruscan Origins of Rome and ItalyThe Etruscan Origins of Rome and Italy

A clip about the history of the Etruscans. Not much is known about them except for what has been found in the form of art, in burial sites and the occasional... -

Etruscan Art at the Louvre - L'Art Etrusque - L'arte degli Etruschi

Etruscan Art at the Louvre - L'Art Etrusque - L'arte degli EtruschiEtruscan Art at the Louvre - L'Art Etrusque - L'arte degli Etruschi

Etruscan Canopic Urn from Chiusi Canthare janiforme Sarcophagus of Cerveteri Couple 520BCE. -

Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part one)

Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part one)Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part one)

Aired on Channel Four (UK) in 2002 and co-produced by Gedeon Programmes; ARTE France; CNRS Images/Media; Le Musee De Louvre. -

M4 Etruscan Art

M4 Etruscan ArtM4 Etruscan Art

Made with Explain Everything -

Etruscans prt 1

Etruscans prt 1Etruscans prt 1

MORE: http://gekos.no/workshop/video.html The Etruscans, who lived in Etruria, were known as Tyrrhenians by the Greeks. They were at their height in Italy fr... -

Etruscan Women

Etruscan WomenEtruscan Women

Twenty-five hundred years ago, Etruscan women living in the Italian region of what is now called Tuscany were afforded a remarkably equal status with men. An... -

Arte Etrusca - Etruscan Art

Arte Etrusca - Etruscan ArtArte Etrusca - Etruscan Art

Gli alunni della classe clp13, 1P 2013/2014 del Liceo Enrico Fermi di Bologna, Vi riassumono il concetto di Arte Etrusca The students of the class clp13, 1P 2013/2014 of the high school Enrico Fermi of Bologna reassume the concept of Etruscan Art, enjoy !o) -

Italian Ancient Art Roman Greek Etruscan Traditions Italia Italy Old World Europe by BK Bazhe.com

Italian Ancient Art Roman Greek Etruscan Traditions Italia Italy Old World Europe by BK Bazhe.comItalian Ancient Art Roman Greek Etruscan Traditions Italia Italy Old World Europe by BK Bazhe.com

Italian Ancient Art - http://www.BAZHE.com Italian - Roman Art, Italia Italian Ancient Art is one of Europe's best, incorporating: the stunning Etruscan, Rom... -

The Etruscan, Greek and Roman Collections - Florence

The Etruscan, Greek and Roman Collections - FlorenceThe Etruscan, Greek and Roman Collections - Florence

The Archaeological Museum of Florence is situated in the heart of the city, in Palazzo della Crocetta, once the residence of Maria Maddalena de'Medici. Creat... -

Jewellery making gold glue solder for etruscan granulations, ancient goldsmiths enamel

Jewellery making gold glue solder for etruscan granulations, ancient goldsmiths enamelJewellery making gold glue solder for etruscan granulations, ancient goldsmiths enamel

Learn ancient goldsmiths art. Making antique reaction solder. In this video, I show my developed art with Chrysocolla stone from the Greek Chrysos (gold) and Kolla (glue) =gold glue (Goldleim) to soldering. The advantages are: high gloss after soldering, no polishing, high melting point and thus ideal for enameling Antique reaction soldering, so that the old Goldsmith's art will not be forgotten. More information on my Homepage www.Goldleim.de -

Funerary Art of the Etruscans

Funerary Art of the EtruscansFunerary Art of the Etruscans

Paul Denis, Associate Curator, World Cultures, Royal Ontario Museum, describes the cinerary chest (200 BC) and the practices of the Etruscans towards the dec... -

Etruscan Girl by "the NaYs"

Etruscan Girl by "the NaYs"Etruscan Girl by "the NaYs"

A young man falls in love with a picture of an Etruscan flute girl in his Art History book leading to a fanciful song about the imaginary relationship he cou... -

History of Art 5. Ancient Roman

History of Art 5. Ancient RomanHistory of Art 5. Ancient Roman

Ancient Roman. Fine Arts and Art History. Etruscan. Rome. Ókori Róma művészete. MUSIC: Arnold_Wohler - Adagio fur Orchester Colosseum KÉPJEGYZÉK: Etruscan, R... -

We Speak Etruscan - Lee Hyla

We Speak Etruscan - Lee HylaWe Speak Etruscan - Lee Hyla

Lee Hyla's "We Speak Etruscan". From the Mobtown Modern "Low Art" Program, recorded October 7th, 2009 at the Metro Gallery in Baltimore, MD. Performed by Bri... -

Musée Maillol spotlights the Etruscans - le mag

Musée Maillol spotlights the Etruscans - le magMusée Maillol spotlights the Etruscans - le mag

A new exhibition at the Musée Maillol in Paris spotlights the culture of the Etruscan people, who... euronews, the most watched news channel in Europe Subscribe for your daily dose of international news, curated and explained:http://eurone.ws/10ZCK4a Euronews is available in 13 other languages: http://eurone.ws/17moBCU http://www.euronews.com/2013/10/28/musee-maillol-spotlights-the-etruscans A new exhibition at the Musée Maillol in Paris spotlights the culture of the Etruscan people, who predated the Romans as leaders among the Mediterranean's great civilisations. The discovery of many graves during the 19th century constituted archaeologi -

Etruscans, The Ancient Centers of Lazio ABNewsTV

Etruscans, The Ancient Centers of Lazio ABNewsTVEtruscans, The Ancient Centers of Lazio ABNewsTV

Etruscans, The Ancient Centers of Lazio tells the story of the period of maximum prosperity and expansion of the Etruscan civilization during the 6th and 5th... -

Who restores the Vatican's massive art collection?

Who restores the Vatican's massive art collection?Who restores the Vatican's massive art collection?

http://en.romereports.com From Etruscan art to priceless frescoes and everything in between, the Vatican has hundreds of thousands of art pieces in its collection. But all this beauty comes with responsibility, especially when it comes to restoring this massive collection. -

AKELO: I segreti degli ori etruschi - The Secrets of Etruscan Golden Jewelry

AKELO: I segreti degli ori etruschi - The Secrets of Etruscan Golden JewelryAKELO: I segreti degli ori etruschi - The Secrets of Etruscan Golden Jewelry

Akelo - I segreti degli ori etruschi Filmato tratto dalla trasmissione televisiva: "Ulisse, il piacere della scoperta - Sulle tracce degli Etruschi" di Piero... -

Art and Splendor of the Etruscans: Caere

Art and Splendor of the Etruscans: CaereArt and Splendor of the Etruscans: Caere

In this video you will see how Caere, modern day Cerveteri, Italy, dominated culture, art and craftmanship in ancient Italy for many centuries. The Etruscans... -

Etruscan Museum

Etruscan MuseumEtruscan Museum

the Etruscan Archaeological Museum; Chianciano, Tuscany, Italy. -

Ancient Etruscan House Discovered

Ancient Etruscan House DiscoveredAncient Etruscan House Discovered

http://www.discoverynews.com For the first time, Italian archaeologists have uncovered an intact Etruscan house. Researchers hope this find sheds light on th... -

etruscan burial practice british museum

etruscan burial practice british museumetruscan burial practice british museum

- published: 05 Oct 2013

- views: 38

- Duration: 7:50

- Updated: 15 Aug 2013

- published: 16 Dec 2010

- views: 13155

- author: eIectrostatic

- Duration: 2:33

- Updated: 03 Aug 2013

- published: 02 Jul 2012

- views: 692

- author: Sculptures Paintings Architecture

- Duration: 13:46

- Updated: 12 Oct 2013

- published: 12 Oct 2013

- views: 7

- Duration: 11:48

- Updated: 07 Jun 2014

- published: 07 Jun 2014

- views: 4

- Duration: 9:49

- Updated: 12 Aug 2013

- published: 05 Jan 2012

- views: 3709

- author: kunstskole

- Duration: 9:18

- Updated: 03 Aug 2013

- published: 26 Mar 2012

- views: 1670

- author: Tanguy de Thuret

- Duration: 1:17

- Updated: 15 May 2014

- published: 15 May 2014

- views: 1

- Duration: 6:05

- Updated: 08 Jul 2013

- published: 25 Jul 2008

- views: 3795

- author: BAZHE

- Duration: 1:11

- Updated: 09 Dec 2012

- published: 09 Dec 2012

- views: 46

- author: EdizioniTSMOfficial

- Duration: 9:45

- Updated: 25 Aug 2013

- published: 25 Aug 2013

- views: 205

- Duration: 1:27

- Updated: 02 Apr 2013

- published: 13 Jul 2012

- views: 423

- author: RoyalOntarioMuseum

- Duration: 4:05

- Updated: 06 Aug 2013

- published: 22 Dec 2008

- views: 6068

- author: widecrossing

- Duration: 9:28

- Updated: 04 Jun 2013

- published: 23 Feb 2013

- views: 459

- author: poendrawing

- Duration: 8:39

- Updated: 02 Jan 2013

- published: 17 Feb 2010

- views: 2190

- author: mobtownmodern

- Duration: 1:54

- Updated: 28 Oct 2013

- published: 28 Oct 2013

- views: 223

- Duration: 4:37

- Updated: 24 Jul 2013

- published: 19 Jan 2009

- views: 8424

- author: abnewstv

- Duration: 2:18

- Updated: 13 Oct 2013

- published: 13 Oct 2013

- views: 127

- Duration: 2:27

- Updated: 05 Jul 2013

- published: 01 Dec 2012

- views: 1120

- author: akeloIT

- Duration: 3:50

- Updated: 03 Apr 2013

- published: 29 Oct 2008

- views: 7277

- author: Eirene001

- Duration: 1:21

- Updated: 25 Feb 2013

- published: 25 Feb 2013

- views: 26

- author: Art Witkowski

- Duration: 2:55

- Updated: 03 Aug 2013

- published: 10 Jun 2010

- views: 16934

- author: Discovery

- Duration: 2:06

- Updated: 06 Jul 2013

http://wn.com/etruscan_burial_practice_british_museum

-

SECRETS OF ARCHAEOLOGY: A Place Called Etruria (Ancient History Documentary)

SECRETS OF ARCHAEOLOGY: A Place Called Etruria (Ancient History Documentary)SECRETS OF ARCHAEOLOGY: A Place Called Etruria (Ancient History Documentary)

SECRETS OF ARCHAEOLOGY: A Place Called Etruria (Ancient History Documentary) Take a virtual reality tour of history's most intriguing ancient civilizations. Uncover the secrets of the pyramids as the Pharaohs reach for immortality, walk the streets of the Eternal City of Rome, relive a step-by-step reconstruction of Pompeii under the shadow of mighty Vesuvius, experience life in bustling Baghdad and journey to Latin America to the mythical "El Dorado." SECRETS OF ARCHAEOLOGY makes history come alive! A PLACE CALLED ETRURIA Go on a journey to the ancient cities Volterra, Populonia and Cervetari and see why Etruscan civilization was famous fo -

An Italian Adventure: Etruscan Tombs and Ostia

An Italian Adventure: Etruscan Tombs and OstiaAn Italian Adventure: Etruscan Tombs and Ostia

Our day at the Etruscan Cemetery site of Necropoli Della Banditiaccia and the port city site of Ostia Antica. We did go to the Spanish Steps that night, but my pictures turned out badly and I took no video, so you can just google the Spanish Steps if you don't already know what they look like. Rome, Italy Nov. 9 2013 All video and pictures are mine. Disclaimer: I do not own the music used. 'Toilet' lecture by Dr. Browning. Pictures In Order of Appearance: Picture 1: A giant tumulus tomb at Necropoli Etrusche- Necropoli Della Banditaccia- An Etruscan Tomb complex. Picture 2: A tumulus tomb and ground tomb from the Necropoli Della Bandi -

A HISTORY OF ROME - THE ETRUSCANS AND ROME - PART 2 OF 32

A HISTORY OF ROME - THE ETRUSCANS AND ROME - PART 2 OF 32A HISTORY OF ROME - THE ETRUSCANS AND ROME - PART 2 OF 32

A HISTORY OF ROME - THE ETRUSCANS AND ROME - PART 2 OF 32. -

Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part three)

Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part three)Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part three)

Aired on Channel Four (UK) in 2002 and co-produced by Gedeon Programmes; ARTE France; CNRS Images/Media; Le Musee De Louvre. -

The Vatican Museum Comprehensive Tour (Part 1)

The Vatican Museum Comprehensive Tour (Part 1)The Vatican Museum Comprehensive Tour (Part 1)

(www.ARoadRetravelec.com) Our comprehensive tour of the Vatican Museums starts with the first piece of ancient art that started the entire museum! Also naked controversy: why are the privates of nude males missing, covered with fig leaves, or anatomically too small? In this episode we visit the Etruscan Museum, Egyptian Museum, the Round Room, and many fascinating ancient works of art. -

Meet the Artist: Dante Marioni

Meet the Artist: Dante MarioniMeet the Artist: Dante Marioni

Dante Marioni's sophisticated and boldly colored contemporary vessels are inspired by ancient Greek and Etruscan forms that reflect the rich history of class... -

Christopher Hitchens on Lost and Stolen Art of Ancient Civilizations (2009)

Christopher Hitchens on Lost and Stolen Art of Ancient Civilizations (2009)Christopher Hitchens on Lost and Stolen Art of Ancient Civilizations (2009)

Art theft is usually for the purpose of resale or for ransom (sometimes called artnapping). Stolen art is sometimes used by criminals as collateral to secure loans. Only a small percentage of stolen art is recovered—estimates range from 5 to 10%. This means that little is known about the scope and characteristics of art theft. In the public sphere, Interpol, the FBI Art Crime Team led by special agent Robert King Wittman, London's Metropolitan Police, New York Police Department's special frauds squad[6] and a number of other law enforcement agencies worldwide maintain "squads" dedicated to investigating thefts of this nature and recovering s -

CMEAC Symposium. Rozmeri Basic. March 7, 2013. Paper 01

CMEAC Symposium. Rozmeri Basic. March 7, 2013. Paper 01CMEAC Symposium. Rozmeri Basic. March 7, 2013. Paper 01

Lycian and Etruscan Rock Cut Tombs Interdisciplinary Symposium on Middle Eastern Architecture and Culture March 7-8 2013 College of Architecture, The Univers... -

Mrs. Peters Art History Review Part 2: Egyptian and Greek

Mrs. Peters Art History Review Part 2: Egyptian and GreekMrs. Peters Art History Review Part 2: Egyptian and Greek

My memory card filled up in the middle of recording this and I didn't realize until I went to check on the video when Mrs. Peters called for the pizza. I'm soooo sorry! The whole Greek period should be on here through the Archaic though. The only thing missing is Classical and Hellenistic from Greek, and the Roman period (starting with Etruscan and going through the Republican and Empirical halves through Constantine). I know those parts are crucial, especially Rome since there's nothing posted on that, and again I'm really sorry! I've made sure to clean my memory card out for next time! Hope this is still helpful despite the large chunk of m -

Italy's Great Hill Towns

Italy's Great Hill TownsItaly's Great Hill Towns

In this program, we'll drive through the Tuscan and Umbrian countryside connecting all the hill-town dots, see a ceiling fresco masterpiece NOT by Michelangelo, eat rustic bruschetta, walk a vineyard that goes all the way back to Etruscan times — and more, all while exploring a string of hill-capping medieval towns that somehow manage to keep their heads above the flood of the 21st century. -

Jewellery making gold dust granules

Jewellery making gold dust granulesJewellery making gold dust granules

Jewellery making gold dust granules for etruscan granulation. Soundtrack Produced by Wavetrip. -

ArtTV: Aegean Art Part 1

ArtTV: Aegean Art Part 1ArtTV: Aegean Art Part 1

A tour through ancient Aegean art. -

➜ Total War - Rome 2 Hannibal at the Gates Carthage - Part 31 [Legendary]

➜ Total War - Rome 2 Hannibal at the Gates Carthage - Part 31 [Legendary]➜ Total War - Rome 2 Hannibal at the Gates Carthage - Part 31 [Legendary]

The Etruscan League launches it's attack on one crucial city and it fails. ➜ Donation Link: https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted;_button_id=8D88TAHW5EQRN ➜ Walkthrough Master List: http://costinrazvan.tumblr.com/walkthroughs -

Alan Wilson & Baram Blackett - British and Welsh History, the Ancient Coelbren & the Khumry Hour 2

Alan Wilson & Baram Blackett - British and Welsh History, the Ancient Coelbren & the Khumry Hour 2Alan Wilson & Baram Blackett - British and Welsh History, the Ancient Coelbren & the Khumry Hour 2

Authors Baram Blackett and Alan Wilson talk about their 30 year research into the hidden British and Welsh history. They are the authors of King Arthur & the Charters of the Kings, The King Arthur Conspiracy, Moses in the Hieroglyphs, The Discovery of the Ark of the Covenant and The Trojan War of 650 BC. Their forthcoming book is called The Murder of Britain. They talk about their research and the hidden history of the ancient world and the relationship between ancient civilizations. They talk about the Khumric Coelbren Alphabet and the Etruscan Connection. Topics Discussed: solid foundations, the land of charters, amulet, Quentin Hutchinson -

Total war: Rome 2- Ardiaei 3 Assault the League!

Total war: Rome 2- Ardiaei 3 Assault the League!Total war: Rome 2- Ardiaei 3 Assault the League!

We sail over to the Etruscan league and give them a friendly bashing with some axes! -

Study Abroad Art History in Italy, 2012

Study Abroad Art History in Italy, 2012Study Abroad Art History in Italy, 2012

I was in Italy for a month and it was one of the most incredible experiences I've ever had! We were in a classroom for all of four hours and the rest was han... -

Images of Umbria

Images of UmbriaImages of Umbria

A Calming Escape To A Beautiful Place -- Combining breathtaking images and music, filmmaker Danny DeLorenzo takes you on a personal journey to one of the mos... -

Musee du Louvre, Paris, 2013

Musee du Louvre, Paris, 2013Musee du Louvre, Paris, 2013

The Louvre, originally a royal palace but now the world's most famous museum, is a must-visit for anyone with a slight interest in art. Some of the museum's most celebrated works of art include the Mona Lisa and the Venus of Milo.The Louvre Museum is one of the largest and most important museums in the world. It is housed in the expansive Louvre Palace, situated in the 1st arrondissement, at the heart of Paris. After entering the museum through the Louvre Pyramid or via the Carrousel du Louvre, you have access to three large wings: Sully, Richelieu and Denon. The Sully wing is the oldest part of the Louvre. The second floor holds a collecti -

Friedrich Kittler. The Roman Scriptural System. 2011

Friedrich Kittler. The Roman Scriptural System. 2011Friedrich Kittler. The Roman Scriptural System. 2011

http://www.egs.edu Friedrich Kittler, German historian and theorist, lecturing on the history of writing. In this lecture he talks about the innovations of t... -

Russain 19th Century Art Lecture with Sean Forester.

Russain 19th Century Art Lecture with Sean Forester.Russain 19th Century Art Lecture with Sean Forester.

Sean Forester from the Golden Gate Atelier in the San Francisco Bay area talks about 19th Century Russian Fine Art. -

Islamic Art by Simple Tree

Islamic Art by Simple TreeIslamic Art by Simple Tree

These widely diverse arts, from an area extending from southern Spain to Central Asia, trace the distinctive visual imagination of Islamic artists over a period of fourteen hundred years. The collection consists of glazed ceramics, inlaid metalwork, enameled glass, carved wood and stone, and manuscript illustration, illumination, and calligraphy. See more great art at simpletreebooks.com -

Belgesel - How Art Made The World

Belgesel - How Art Made The WorldBelgesel - How Art Made The World

http://www.mahmutyalcin.com.tr/ ══════════════════════ Şanlı Türk tarihi, Türkçülük, Turan, Türk Birliği, Tarihe damgasını vuran Türk'... -

Gothic Vaulting

Gothic VaultingGothic Vaulting

Art Historian Dr. Vida Hull ETSU Online Programs - http://www.etsu.edu/online Medieval Art Ub6 Chartres sculptureYT

- Duration: 25:00

- Updated: 06 Apr 2014

- published: 06 Apr 2014

- views: 305

- Duration: 20:21

- Updated: 31 Mar 2014

- published: 31 Mar 2014

- views: 4

- Duration: 22:49

- Updated: 26 Jul 2013

- published: 16 May 2011

- views: 5374

- author: Justin Walsh

- Duration: 22:57

- Updated: 12 Oct 2013

- published: 12 Oct 2013

- views: 7

- Duration: 22:01

- Updated: 10 Nov 2013

- published: 10 Nov 2013

- views: 29

- Duration: 44:49

- Updated: 26 Jun 2013

- published: 26 Sep 2011

- views: 1146

- author: corningmuseumofglass

- Duration: 77:54

- Updated: 20 Jan 2014

- published: 20 Jan 2014

- views: 15

- Duration: 21:05

- Updated: 01 Jun 2013

- published: 19 Apr 2013

- views: 263

- author: Khosrow Bozorgi

- Duration: 24:44

- Updated: 12 Dec 2013

- published: 12 Dec 2013

- views: 15

- Duration: 25:06

- Updated: 19 Aug 2013

- published: 19 Aug 2013

- views: 2375

- Duration: 27:52

- Updated: 07 Sep 2013

- published: 07 Sep 2013

- views: 231

- Duration: 35:01

- Updated: 13 Sep 2013

- published: 13 Sep 2013

- views: 109

![➜ Total War - Rome 2 Hannibal at the Gates Carthage - Part 31 [Legendary] ➜ Total War - Rome 2 Hannibal at the Gates Carthage - Part 31 [Legendary]](http://web.archive.org./web/20140903023521im_/http://i1.ytimg.com/vi/k4fMkilCfUQ/0.jpg)

- Duration: 24:46

- Updated: 17 Jun 2014

- published: 17 Jun 2014

- views: 205

- Duration: 59:20

- Updated: 01 Sep 2013

- published: 01 Sep 2013

- views: 5

- Duration: 46:58

- Updated: 30 May 2014

- published: 30 May 2014

- views: 187

- Duration: 24:39

- Updated: 09 Aug 2013

- published: 09 Aug 2013

- author: Austyn Victoria

- Duration: 66:41

- Updated: 02 Jul 2013

- published: 09 Jan 2010

- views: 24

- author: TravelVideoStore

- Duration: 49:12

- Updated: 18 Jan 2014

- published: 18 Jan 2014

- views: 14

- Duration: 36:00

- Updated: 12 Feb 2013

- published: 05 Jan 2013

- views: 342

- author: egsvideo

- Duration: 33:35

- Updated: 18 Jul 2013

- published: 18 Jul 2013

- views: 20

- Duration: 21:45

- Updated: 04 Nov 2013

- published: 04 Nov 2013

- views: 1

- Duration: 58:01

- Updated: 24 Jun 2013

- published: 18 May 2013

- views: 24

- author: Alp ATA

- Duration: 20:32

- Updated: 11 Apr 2014

- published: 11 Apr 2014

- views: 139

-

Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago | Olddirectory.com

Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago | Olddirectory.comAncient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago | Olddirectory.com

Ancient Greek, Ancient Roman, Byzantine, and Etruscan Art at the Art Institute of Chicago. See more about collectible appraisers, vintage clothing, coins at Olddirectory.com -

AKELO - ANDREA CAGNETTI: The Secrets of Etruscan Golden Jewelry - I Segreti degli Ori Etruschi

AKELO - ANDREA CAGNETTI: The Secrets of Etruscan Golden Jewelry - I Segreti degli Ori EtruschiAKELO - ANDREA CAGNETTI: The Secrets of Etruscan Golden Jewelry - I Segreti degli Ori Etruschi

Akelo - The Secrets of Etruscan Golden Jewelry Video taken from the Italian television transmission: : "Ulisse, Il piacere della scoperta - In the Footsteps of the Etruscans" di Piero ed Alberto Angela (RAI 3). The artist Akelo - Andrea Cagnetti explains the secrets of Etruscan gold working techniques and granulation. http://www.akelo.it/ Akelo - I Segreti degli Ori Etruschi Filmato tratto dalla trasmissione televisiva: "Ulisse, il piacere della scoperta - Sulle tracce degli Etruschi" di Piero ed Alberto Angela (RAI 3) . L'artista Akelo - Andrea Cagnetti spiega i segreti della lavorazione degli ori etruschi e della granulazione. http://www. -

Art of The Etruscans: Mr. Calzada's AP Art History Class Lectures

Art of The Etruscans: Mr. Calzada's AP Art History Class LecturesArt of The Etruscans: Mr. Calzada's AP Art History Class Lectures

Art of The Etruscans -

Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago

Ancient Art at the Art Institute of ChicagoAncient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago

Ancient Greek, Ancient Roman, Byzantine, and Etruscan Art at the Art Institute of Chicago. Producer: Michael Stepanovic Editor: Michael Stepanovic Voice: Gra... -

Susan Raber-Bray - "The Artists of Frog Hollow"

Susan Raber-Bray - "The Artists of Frog Hollow"Susan Raber-Bray - "The Artists of Frog Hollow"

Susan Raber-Bray's work has been influenced by her fascination with Etruscan art. In this episode of "The Artists of Frog Hollow," Susan contemplates societa... -

Antique Grecian Etruscan style (Italian 1940s) glazed eathen

Antique Grecian Etruscan style (Italian 1940s) glazed eathenAntique Grecian Etruscan style (Italian 1940s) glazed eathen

http://www.newel.com/PreviewImage.aspx?ItemID=15421 - Newel.com: Antique Grecian Etruscan style (Italian 1940s) glazed eathenware handled large vase with ani...

- Duration: 5:02

- Updated: 12 Dec 2013

- published: 12 Dec 2013

- views: 2

- Duration: 2:44

- Updated: 20 Nov 2013

- published: 20 Nov 2013

- views: 4

- Duration: 5:52

- Updated: 24 Oct 2013

- published: 24 Oct 2013

- views: 18

- Duration: 5:02

- Updated: 10 May 2013

- published: 10 May 2013

- views: 7

- author: StepanovicProduction

- Duration: 8:37

- Updated: 26 Jul 2012

- published: 09 Jul 2012

- views: 126

- author: retnvt

- Duration: 0:55

- Updated: 21 Jun 2010

- published: 16 Apr 2010

- views: 102

- author: NewelAntiques4

The Etruscan Origins of Rome and Italy

A clip about the history of the Etruscans. Not much is known about them except for what has been found in the form of art, in burial sites and the occasional...- published: 16 Dec 2010

- views: 13155

- author: eIectrostatic

Etruscan Art at the Louvre - L'Art Etrusque - L'arte degli Etruschi

Etruscan Canopic Urn from Chiusi Canthare janiforme Sarcophagus of Cerveteri Couple 520BCE.- published: 02 Jul 2012

- views: 692

- author: Sculptures Paintings Architecture

Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part one)

Aired on Channel Four (UK) in 2002 and co-produced by Gedeon Programmes; ARTE France; CNRS Images/Media; Le Musee De Louvre.- published: 12 Oct 2013

- views: 7

Etruscans prt 1

MORE: http://gekos.no/workshop/video.html The Etruscans, who lived in Etruria, were known as Tyrrhenians by the Greeks. They were at their height in Italy fr...- published: 05 Jan 2012

- views: 3709

- author: kunstskole

Etruscan Women

Twenty-five hundred years ago, Etruscan women living in the Italian region of what is now called Tuscany were afforded a remarkably equal status with men. An...- published: 26 Mar 2012

- views: 1670

- author: Tanguy de Thuret

Arte Etrusca - Etruscan Art

Gli alunni della classe clp13, 1P 2013/2014 del Liceo Enrico Fermi di Bologna, Vi riassumono il concetto di Arte Etrusca The students of the class clp13, 1P 2013/2014 of the high school Enrico Fermi of Bologna reassume the concept of Etruscan Art, enjoy !o)- published: 15 May 2014

- views: 1

Italian Ancient Art Roman Greek Etruscan Traditions Italia Italy Old World Europe by BK Bazhe.com

Italian Ancient Art - http://www.BAZHE.com Italian - Roman Art, Italia Italian Ancient Art is one of Europe's best, incorporating: the stunning Etruscan, Rom...- published: 25 Jul 2008

- views: 3795

- author: BAZHE

The Etruscan, Greek and Roman Collections - Florence

The Archaeological Museum of Florence is situated in the heart of the city, in Palazzo della Crocetta, once the residence of Maria Maddalena de'Medici. Creat...- published: 09 Dec 2012

- views: 46

- author: EdizioniTSMOfficial

Jewellery making gold glue solder for etruscan granulations, ancient goldsmiths enamel

Learn ancient goldsmiths art. Making antique reaction solder. In this video, I show my developed art with Chrysocolla stone from the Greek Chrysos (gold) and Kolla (glue) =gold glue (Goldleim) to soldering. The advantages are: high gloss after soldering, no polishing, high melting point and thus ideal for enameling Antique reaction soldering, so that the old Goldsmith's art will not be forgotten. More information on my Homepage www.Goldleim.de- published: 25 Aug 2013

- views: 205

Funerary Art of the Etruscans

Paul Denis, Associate Curator, World Cultures, Royal Ontario Museum, describes the cinerary chest (200 BC) and the practices of the Etruscans towards the dec...- published: 13 Jul 2012

- views: 423

- author: RoyalOntarioMuseum

Etruscan Girl by "the NaYs"

A young man falls in love with a picture of an Etruscan flute girl in his Art History book leading to a fanciful song about the imaginary relationship he cou...- published: 22 Dec 2008

- views: 6068

- author: widecrossing

History of Art 5. Ancient Roman

Ancient Roman. Fine Arts and Art History. Etruscan. Rome. Ókori Róma művészete. MUSIC: Arnold_Wohler - Adagio fur Orchester Colosseum KÉPJEGYZÉK: Etruscan, R...- published: 23 Feb 2013

- views: 459

- author: poendrawing

We Speak Etruscan - Lee Hyla

Lee Hyla's "We Speak Etruscan". From the Mobtown Modern "Low Art" Program, recorded October 7th, 2009 at the Metro Gallery in Baltimore, MD. Performed by Bri...- published: 17 Feb 2010

- views: 2190

- author: mobtownmodern

Musée Maillol spotlights the Etruscans - le mag

A new exhibition at the Musée Maillol in Paris spotlights the culture of the Etruscan people, who... euronews, the most watched news channel in Europe Subscribe for your daily dose of international news, curated and explained:http://eurone.ws/10ZCK4a Euronews is available in 13 other languages: http://eurone.ws/17moBCU http://www.euronews.com/2013/10/28/musee-maillol-spotlights-the-etruscans A new exhibition at the Musée Maillol in Paris spotlights the culture of the Etruscan people, who predated the Romans as leaders among the Mediterranean's great civilisations. The discovery of many graves during the 19th century constituted archaeologists' primary source of information on the Etruscans. As such, their history is often presented through stories associated with their burial traditions. However, this exhibition explores the daily life of the Etruscans and the culture that developed between the 9th and 2nd centuries BC, in an area that today corresponds to the Italian peninsula. Vincent Jolivet is an expert at the museum: "This exhibition shows that there is not just one Etruscan civilisation and one Etruscan art," he said. "It was truly a diverse population, which was able to integrate all kinds of influences. And it integrated them in a way that was not at all prescriptive or uniform, but instead very diverse depending on the different cities and different eras." With 250 works, from prestigious institutions in Italy and other European countries, the exhibition aims to study the Etruscans in the light of their everyday lives; using architecture to link the first huts to the founding of cities during the seventh century and on to the Roman conquest of Etruria in 351: "The objects are difficult, or rather, interesting to decrypt," Jolivet elaborated. "There are documents which seem to be linked to Egypt, and this could be true. Others recall items from the Phoenician or the Carthaginian world, and that is also true. In addition, the Greek world is very present." The exhibition commemorates the disappearance of a people who left behind a fascinating cultural heritage, which had a profound influence on Rome. Find us on: Youtube http://bit.ly/zr3upY Facebook http://www.facebook.com/euronews.fans Twitter http://twitter.com/euronews- published: 28 Oct 2013

- views: 223

Etruscans, The Ancient Centers of Lazio ABNewsTV

Etruscans, The Ancient Centers of Lazio tells the story of the period of maximum prosperity and expansion of the Etruscan civilization during the 6th and 5th...- published: 19 Jan 2009

- views: 8424

- author: abnewstv

Who restores the Vatican's massive art collection?

http://en.romereports.com From Etruscan art to priceless frescoes and everything in between, the Vatican has hundreds of thousands of art pieces in its collection. But all this beauty comes with responsibility, especially when it comes to restoring this massive collection.- published: 13 Oct 2013

- views: 127

SECRETS OF ARCHAEOLOGY: A Place Called Etruria (Ancient History Documentary)

SECRETS OF ARCHAEOLOGY: A Place Called Etruria (Ancient History Documentary) Take a virtual reality tour of history's most intriguing ancient civilizations. Uncover the secrets of the pyramids as the Pharaohs reach for immortality, walk the streets of the Eternal City of Rome, relive a step-by-step reconstruction of Pompeii under the shadow of mighty Vesuvius, experience life in bustling Baghdad and journey to Latin America to the mythical "El Dorado." SECRETS OF ARCHAEOLOGY makes history come alive! A PLACE CALLED ETRURIA Go on a journey to the ancient cities Volterra, Populonia and Cervetari and see why Etruscan civilization was famous for its extravagant wealth, fine ceramics, handicrafts and bustling trade, and how it was all lost in battles with the Greek colonies in southern Italy.- published: 06 Apr 2014

- views: 305

An Italian Adventure: Etruscan Tombs and Ostia

Our day at the Etruscan Cemetery site of Necropoli Della Banditiaccia and the port city site of Ostia Antica. We did go to the Spanish Steps that night, but my pictures turned out badly and I took no video, so you can just google the Spanish Steps if you don't already know what they look like. Rome, Italy Nov. 9 2013 All video and pictures are mine. Disclaimer: I do not own the music used. 'Toilet' lecture by Dr. Browning. Pictures In Order of Appearance: Picture 1: A giant tumulus tomb at Necropoli Etrusche- Necropoli Della Banditaccia- An Etruscan Tomb complex. Picture 2: A tumulus tomb and ground tomb from the Necropoli Della Banditaccia, the Etruscan Tomb complex. Picture 3: A ground tomb, at its entrance are carved items symbolic of the people buried in the tomb. A carved house indicates a woman, the carved circular pillar object, representing a specific male anatomy part, indicated a male. Picture 4: The Tomba dei Rilievi, the long stairway leads down into the hypogeum tomb of the wealthy Matuna family, which boasts carvings in the walls and pillars above the burial niches. On the wall are mythical creatures from the afterlife, on the pillars and around the mythical depiction are carvings of weapons, shields and household objects. Tombs were considered homes, often mirroring the homes of the living; this home is extravagantly decorated with the objects of daily living. Picture 5: The Tomba della Cornice, the tomb slab on the far wall is where the 'Smiling Couple' terracotta coffin top was set over a body. A stone chair is next to the door and another slab. Beyond the carved doorways are more slabs for the bodies of the family that owned the tomb of the Cornice. Picture 6: A slab carved into the wall, not part of an extensive tomb, but a slab with stone pillow in a wall in the Etruscan Tomb site. Picture 7: A little bit of Lady Liberty on a truck in Italy. A little bit of home. Picture 8: A mosaic floor of sea creatures surrounding Neptune in a sea-chariot pulled by giant sea horses. In the Terme di Nettuno: The bath house complex of Neptune in Ostia. Picture 9: A mosaic, which announced the shipping business office that would have occupied the small room/stall. These little rooms and mosaic business signs circled the Piazzale della Corporazioni which was a garden with a temple at the center. Picture 10: One wall in a bathhouse at Ostia, of the 'Seven Sages' who are all giving advice on how to have a good poop. The Bathhouse of the Seven Sages was mentioned in the toilet lecture, one of the sages is the one talking about the sponge on a stick. Picture 11: Another sections of the walls with the depictions of the Seven Sages from the bathhouse. Picture 12: A smaller section from the Seven Sages bathhouse, this wall depicting one of the Sages. Picture 13: A synagogue building in Ostia, separated from most of the city, pictured is the elevated area that would have had a cupboard, called the 'Shrine of the Book' that would have held the synagogues Torah and other books. At the top of the pillars, on the underside of the pillar-toppers, are carved Menorahs. Picture 14: Sitting on the remains of a toilet complex, Meghan is holding a stick with a pine cone- representing the sponge on a stick. Picture 15: "TO THE TOILETS!" It's the new "Charge!" statement. (After the video) Picture 16: A picture of one section of graves from the American Military Cemetery, all men from World War II. Picture 17: Another section of graves from the American Military Cemetery. There are also graves with the Star of David on the cross indicating a soldier of Jewish decent and faith. Picture 18: Some graves hold soldiers that could not be identified or named, their crosses simply read: Here Rests in Honored Glory A Comrade in Arms Known but to God- published: 31 Mar 2014

- views: 4

A HISTORY OF ROME - THE ETRUSCANS AND ROME - PART 2 OF 32

A HISTORY OF ROME - THE ETRUSCANS AND ROME - PART 2 OF 32.- published: 16 May 2011

- views: 5374

- author: Justin Walsh

Lost Worlds - Enigma Of The Etruscans (part three)

Aired on Channel Four (UK) in 2002 and co-produced by Gedeon Programmes; ARTE France; CNRS Images/Media; Le Musee De Louvre.- published: 12 Oct 2013

- views: 7

The Vatican Museum Comprehensive Tour (Part 1)

(www.ARoadRetravelec.com) Our comprehensive tour of the Vatican Museums starts with the first piece of ancient art that started the entire museum! Also naked controversy: why are the privates of nude males missing, covered with fig leaves, or anatomically too small? In this episode we visit the Etruscan Museum, Egyptian Museum, the Round Room, and many fascinating ancient works of art.- published: 10 Nov 2013

- views: 29

Meet the Artist: Dante Marioni

Dante Marioni's sophisticated and boldly colored contemporary vessels are inspired by ancient Greek and Etruscan forms that reflect the rich history of class...- published: 26 Sep 2011

- views: 1146

- author: corningmuseumofglass

Christopher Hitchens on Lost and Stolen Art of Ancient Civilizations (2009)

Art theft is usually for the purpose of resale or for ransom (sometimes called artnapping). Stolen art is sometimes used by criminals as collateral to secure loans. Only a small percentage of stolen art is recovered—estimates range from 5 to 10%. This means that little is known about the scope and characteristics of art theft. In the public sphere, Interpol, the FBI Art Crime Team led by special agent Robert King Wittman, London's Metropolitan Police, New York Police Department's special frauds squad[6] and a number of other law enforcement agencies worldwide maintain "squads" dedicated to investigating thefts of this nature and recovering stolen works of art. According to Robert K. Wittman, a former FBI agent who led the Art Crime Team until his retirement in 2008, the unit is very small compared with similar law-enforcement units in Europe, and most art thefts investigated by the FBI involve agents at local offices who handle routine property theft. "Art and antiquity crime is tolerated, in part, because it is considered a victimless crime," Wittman said in 2010.[5] Because antiquities are often regarded by the country of origin as national treasures, there are numerous cases where artworks (often displayed in the acquiring country for decades) have become the subject of highly charged and political controversy. One prominent example is the case of the Elgin Marbles, which were moved from Greece to the British Museum in 1816 by Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin. Many different Greek governments have maintained that removal was tantamount to theft.[7] Similar controversies have arisen over Etruscan, Aztec, and Italian artworks, with advocates of the originating countries generally alleging that the removal of artifacts is a pernicious form of cultural imperialism. Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History is engaged (as of November 2006) in talks with the government of Peru about possible repatriation of artifacts taken during the excavation of Machu Picchu by Yale's Hiram Bingham. In 2006, New York's Metropolitan Museum reached an agreement with Italy to return many disputed pieces. The Getty Museum in Los Angeles is also involved in a series of cases of this nature. The artwork in question is of Greek and ancient Italian origin. The museum agreed on November 20, 2006, to return 26 contested pieces to Italy. One of the Getty's signature pieces, a statue of the goddess Aphrodite, is the subject of particular scrutiny. From 1933 through the end of World War II, the Nazi regime maintained a policy of looting art for sale or for removal to museums in the Third Reich. Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, personally took charge of hundreds of valuable pieces, generally stolen from Jews and other victims of the Holocaust. Members of the families of the original owners of these artworks have, in many cases, persisted in claiming title to their pre-war property. In 2006, after a protracted court battle in the United States and Austria (see Republic of Austria v. Altmann), five paintings by Austrian artist Gustav Klimt were returned to Maria Altmann, the niece of pre-war owner, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer. Two of the paintings were portraits of Altmann's aunt, Adele. The more famous of the two, the gold Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, was sold in 2006 by Altmann and her co-heirs to philanthropist Ronald Lauder for $135 million. At the time of the sale, it was the highest known price ever paid for a painting. The remaining four restituted paintings were later sold at Christie's New York for over $190 million. Film How to Steal a Million (1966), about the recovery from a Paris museum of a fake Cellini committed by the character's grandfather, before its discovery and exposure as such. Gambit (1966), starring Michael Caine and Shirley MacLaine Once a Thief (1991), directed by John Woo, follows a trio of art-thieves in Hong Kong who stumble across a valuable cursed painting. Hudson Hawk (1991) centers on a cat burglar who is forced to steal Da Vinci works of art for a world domination plot. In the 1999 remake of The Thomas Crown Affair, the title character is a stylish, debonair playboy who steals art for amusement rather than for the money (the earlier 1968 film arranges the theft of cash from banks, not art). In Entrapment (1999), an insurance agent is persuaded to join the world of art theft by an aging master thief. Ocean's Twelve (2004) involves the theft of four paintings (including Blue Dancers by Edgar Degas) and the main plot revolves around a competition to steal a Fabergé egg. The Maiden Heist (2009), three museum security guards who devise a plan to steal back the artworks to which they have become attached after they are transferred to another museum. Headhunters (2011), a corporate recruiter who doubles as an art thief sets out to steal a Rubens painting from one of his job prospects. Trance (2013) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stolen_art- published: 20 Jan 2014

- views: 15

CMEAC Symposium. Rozmeri Basic. March 7, 2013. Paper 01

Lycian and Etruscan Rock Cut Tombs Interdisciplinary Symposium on Middle Eastern Architecture and Culture March 7-8 2013 College of Architecture, The Univers...- published: 19 Apr 2013

- views: 263

- author: Khosrow Bozorgi

Mrs. Peters Art History Review Part 2: Egyptian and Greek

My memory card filled up in the middle of recording this and I didn't realize until I went to check on the video when Mrs. Peters called for the pizza. I'm soooo sorry! The whole Greek period should be on here through the Archaic though. The only thing missing is Classical and Hellenistic from Greek, and the Roman period (starting with Etruscan and going through the Republican and Empirical halves through Constantine). I know those parts are crucial, especially Rome since there's nothing posted on that, and again I'm really sorry! I've made sure to clean my memory card out for next time! Hope this is still helpful despite the large chunk of missing information.- published: 12 Dec 2013

- views: 15

Italy's Great Hill Towns

In this program, we'll drive through the Tuscan and Umbrian countryside connecting all the hill-town dots, see a ceiling fresco masterpiece NOT by Michelangelo, eat rustic bruschetta, walk a vineyard that goes all the way back to Etruscan times — and more, all while exploring a string of hill-capping medieval towns that somehow manage to keep their heads above the flood of the 21st century.- published: 19 Aug 2013

- views: 2375

Jewellery making gold dust granules

Jewellery making gold dust granules for etruscan granulation. Soundtrack Produced by Wavetrip.- published: 07 Sep 2013

- views: 231

➜ Total War - Rome 2 Hannibal at the Gates Carthage - Part 31 [Legendary]

The Etruscan League launches it's attack on one crucial city and it fails. ➜ Donation Link: https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted;_button_id=8D88TAHW5EQRN ➜ Walkthrough Master List: http://costinrazvan.tumblr.com/walkthroughs- published: 17 Jun 2014

- views: 205

Alan Wilson & Baram Blackett - British and Welsh History, the Ancient Coelbren & the Khumry Hour 2

Authors Baram Blackett and Alan Wilson talk about their 30 year research into the hidden British and Welsh history. They are the authors of King Arthur & the Charters of the Kings, The King Arthur Conspiracy, Moses in the Hieroglyphs, The Discovery of the Ark of the Covenant and The Trojan War of 650 BC. Their forthcoming book is called The Murder of Britain. They talk about their research and the hidden history of the ancient world and the relationship between ancient civilizations. They talk about the Khumric Coelbren Alphabet and the Etruscan Connection. Topics Discussed: solid foundations, the land of charters, amulet, Quentin Hutchinson, history can be a paradox, King Arthur, linguistic divide, the banning of Welsh in Britain in 1846, invasion, King of Syria, Hittite King, Khumric people, second invasion by Brutus, Cardinal Baronius, Christianity, KHUMRI, deciphering the stone, Robert Williams, catastrophe, Holland (Holy Land), comet, Ogam alphabet, Barry Fell, Egypt, Britain, Aegean, Wallace Budge and more. We continue to talk with Alan Wilson in our members section about misdating and historical chronology. Also, we discuss the Ark of the Covenant. Then, Alan talks about cultural genocide and his excursion into the field. He shares his discoveries of constellations or astrological signs in the landscapes of Wales. We also talk about Alan's translation of the Etruscan Alphabet and Egyptian hieroglyphics. This is an interesting continuation that ties things together in regards to Alan and Baram's research. Topics Discussed: misdating, St Patrick, the eruption of Krakatoa, The Ark of the Covenant, Etruscan inscriptions, the Etruscan language, reading Egyptian hieroglyphics, the search for the grail, Greal, Sirius, Hercules, Capricorn and constellations or astrological signs in the landscapes of Wales. Alan Wilson and his life-long fellow researcher Baram Blackett have written and published nine books. Their books published to date (oldest first) are as follows: 1 - Arthur, King of Glamorgan and Gwent. 2 - Arthur and the Charter of Kings. 3 - Arthur the War King 4 - Artorius Rex Discovered 5 - The Holy Kingdom 6 - The King Arthur Conspiracy 7 - Moses in the Hieroglyphs 8 - The Discovery of the Ark of the Covenant 9 - The Trojan War of 650 BC- published: 01 Sep 2013

- views: 5

Total war: Rome 2- Ardiaei 3 Assault the League!

We sail over to the Etruscan league and give them a friendly bashing with some axes!- published: 30 May 2014

- views: 187

Study Abroad Art History in Italy, 2012

I was in Italy for a month and it was one of the most incredible experiences I've ever had! We were in a classroom for all of four hours and the rest was han...- published: 09 Aug 2013

- author: Austyn Victoria

Images of Umbria

A Calming Escape To A Beautiful Place -- Combining breathtaking images and music, filmmaker Danny DeLorenzo takes you on a personal journey to one of the mos...- published: 09 Jan 2010

- views: 24

- author: TravelVideoStore

Musee du Louvre, Paris, 2013

The Louvre, originally a royal palace but now the world's most famous museum, is a must-visit for anyone with a slight interest in art. Some of the museum's most celebrated works of art include the Mona Lisa and the Venus of Milo.The Louvre Museum is one of the largest and most important museums in the world. It is housed in the expansive Louvre Palace, situated in the 1st arrondissement, at the heart of Paris. After entering the museum through the Louvre Pyramid or via the Carrousel du Louvre, you have access to three large wings: Sully, Richelieu and Denon. The Sully wing is the oldest part of the Louvre. The second floor holds a collection of French paintings, drawings and prints. One of the highlights is the erotic Turkish Bath, painted in the late 18th century by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The first and ground floors of the Sully wing display works from the enormous collection of antiquities. In the 30 rooms with Egyptian antiquities you find artifacts and sculptures from Ancient Egypt such as the famous Seated Scribe and a colossal statue of Pharaoh Ramesses II. On the ground floor is the statue of Aphrodite, better known as the 'Venus of Milo', one of the highlights of the Louvre's Greek collection. Paintings from the Middle Ages up to the 19th century from across Europe are on the second floor of the Richelieu wing, including many works from master painters such as Rubens and Rembrandt. Some of the most notable works are the Lacemaker from Jan Vermeer and the Virgin of Chancellor Rolin, a 15th century work by the Flemish painter Jan van Eyck. The first floor of the Richelieu wing houses a collection of decorative arts, with objects such as clocks, furniture, china and tapestries. Richelieu Wing On the same floor are the sumptuously decorated Napoleon III Apartments. They give you an idea of what the Louvre interior looked like when it was still in use as a royal palace. The ground and lower ground floor are home to the Louvre's extensive collection of sculptures. They are arranged around two glass covered courtyards: Cour Puget and Cour Marly. The latter houses the Horses of Marly, large marble sculptures created in the 18th century by Guillaume Coustou. Nearby is the Tomb of Philippe Pot, supported by eight Pleurants ('weepers'). Denon Wing The Denon Wing is the most crowded of the three wings of the Louvre Museum; the Mona Lisa, a portrait of a woman by Leonardo da Vinci on the first floor is the biggest crowd puller. There are other masterpieces however, including the Wedding Feast at Cana from Veronese and the Consecration of Emperor Napoleon I by Jacques Louis David. Another star attraction of the museum is the Winged Victory of Samothrace, a Greek marble statue displayed at a prominent spot in the atrium connecting the Denon wing with the Sully wing. The ground floor of the Denon wing houses the museum's large collection of Roman and Etruscan antiquities as well as a collection of sculptures from the Renaissance to the 19th century. Here you find Antonio Canova's marble statue of Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss. Even more famous is Michelangelo's Dying Slave. On the same floor are eight rooms with artifacts from Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas. Medieval sculptures from Europe are displayed on the lower ground floor of the Denon wing. source: http://www.aviewoncities.com/paris/louvre.htm- published: 18 Jan 2014

- views: 14

Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago | Olddirectory.com

Ancient Greek, Ancient Roman, Byzantine, and Etruscan Art at the Art Institute of Chicago. See more about collectible appraisers, vintage clothing, coins at Olddirectory.com- published: 12 Dec 2013

- views: 2

AKELO - ANDREA CAGNETTI: The Secrets of Etruscan Golden Jewelry - I Segreti degli Ori Etruschi

Akelo - The Secrets of Etruscan Golden Jewelry Video taken from the Italian television transmission: : "Ulisse, Il piacere della scoperta - In the Footsteps of the Etruscans" di Piero ed Alberto Angela (RAI 3). The artist Akelo - Andrea Cagnetti explains the secrets of Etruscan gold working techniques and granulation. http://www.akelo.it/ Akelo - I Segreti degli Ori Etruschi Filmato tratto dalla trasmissione televisiva: "Ulisse, il piacere della scoperta - Sulle tracce degli Etruschi" di Piero ed Alberto Angela (RAI 3) . L'artista Akelo - Andrea Cagnetti spiega i segreti della lavorazione degli ori etruschi e della granulazione. http://www.akelo.it/- published: 20 Nov 2013

- views: 4

Art of The Etruscans: Mr. Calzada's AP Art History Class Lectures

Art of The Etruscans- published: 24 Oct 2013

- views: 18

Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago

Ancient Greek, Ancient Roman, Byzantine, and Etruscan Art at the Art Institute of Chicago. Producer: Michael Stepanovic Editor: Michael Stepanovic Voice: Gra...- published: 10 May 2013

- views: 7

- author: StepanovicProduction

Susan Raber-Bray - "The Artists of Frog Hollow"

Susan Raber-Bray's work has been influenced by her fascination with Etruscan art. In this episode of "The Artists of Frog Hollow," Susan contemplates societa...- published: 09 Jul 2012

- views: 126

- author: retnvt

Antique Grecian Etruscan style (Italian 1940s) glazed eathen

http://www.newel.com/PreviewImage.aspx?ItemID=15421 - Newel.com: Antique Grecian Etruscan style (Italian 1940s) glazed eathenware handled large vase with ani...- published: 16 Apr 2010

- views: 102

- author: NewelAntiques4

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Next page »

Etruscan art was the form of figurative art produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 9th and 2nd centuries BC. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta (particularly life-size on sarcophagi or temples) and cast bronze, wall-painting and metalworking (especially engraved bronze mirrors and situlae).

The origins of the Etruscans, and consequently of their artistic style, dates back to the people who inhabited or were expelled from Asia Minor during the Bronze Age and Iron Age (See the Villanovan culture). Due to the proximity and/or commercial contact to Etruria, other ancient cultures influenced Etruscan art, such as Greece, Phoenicia, Egypt, Assyria and the Middle East. The apparent simple character in the Hellenistic era conceals an innovative,and unique style whose pinnacle coincided with the Greek archaic period. The Romans would later come to absorb the Etruscan culture into theirs but would also be greatly influenced by them and their art.

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

Lee Hyla (born August 31, 1952, Niagara Falls, New York) is an American classical music composer.

Lee Hyla was born in Niagara Falls, New York, and grew up in Greencastle, Indiana. He has written for numerous performers including the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, the Kronos Quartet (with Allen Ginsberg), The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Speculum Musicae, the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, the Lydian String Quartet, Triple Helix, Tim Smith, Tim Berne, Laura Frautschi, Rhonda Rider, Stephen Drury, Mia Chung, Judith Gordon, Mary Nessinger, Boston Musica Viva, and House Blend, the resident ensemble at the Kitchen.

Hyla has received commissions from the Koussevitzky, Fromm, Barlow, and Naumburg foundations, the Mary Flagler Carey Charitable Trust, Concert Artist's Guild, three commissions from Chamber Music America and two Meet the Composer/Reader's Digest Consortium commissions. He has also been the recipient of the Stoeger Prize from the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, a Guggenheim Fellowship, two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, the Goddard Lieberson Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the St. Botolph Club Award, and the Rome Prize.

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.