Landscape is one of the principal types or genres of subject in Western art

Flatford Mill ('Scene on a Navigable River') 1816-17

Oil on canvas

- Introduction to the landscape genre

- Development of landscape

- Artists in focus

- Landscape in context

- Landscape in detail

Introduction to the landscape genre

The appreciation of nature for its own sake, and its choice as a specific subject for art, is a relatively recent phenomenon. Until the seventeenth century landscape was confined to the background of portraits or paintings dealing principally with religious, mythological or historical subjects (History painting).

In the work of the seventeenth-century painters Claude Lorraine and Nicholas Poussin, the landscape background began to dominate the history subjects that were the ostensible basis for the work. Their treatment of landscape however was highly stylised or artificial: they tried to evoke the landscape of classical Greece and Rome and their work became known as classical landscape. At the same time Dutch landscape painters such as Jacob van Ruysdael were developing a much more naturalistic form of landscape painting, based on what they saw around them.

Landscape with Rainbow, Henley-on-Thames circa 1690

Oil on canvas

support: 819 x 1029 mm

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1967

When, also in the seventeenth century, the French Academy classified the genres of art, it placed landscape fourth in order of importance out of five genres. Nevertheless, landscape painting became increasingly popular through the eighteenth century, although the classical idea predominated.

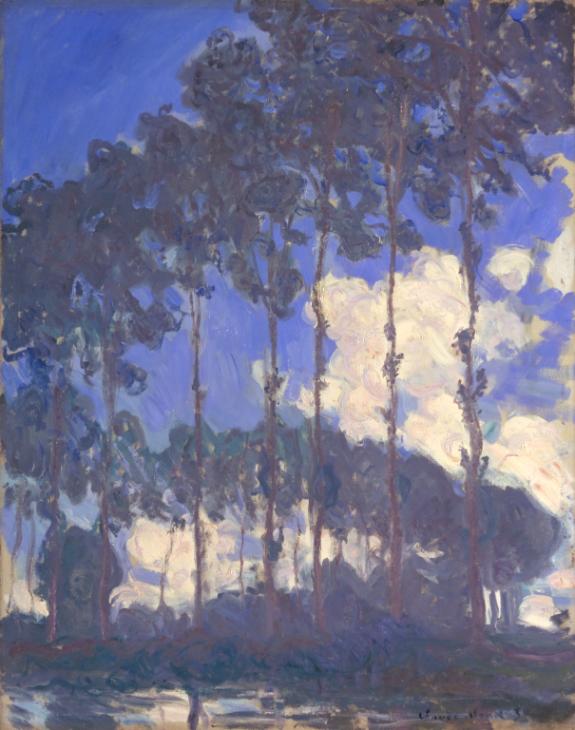

The nineteenth century, however, saw a remarkable explosion of naturalistic landscape painting, partly driven it seems by the notion that nature is a direct manifestation of God, and partly by the increasing alienation of many people from nature by growing industrialisation and urbanisation. Britain produced two outstanding contributors to this phenomenon in John Constable and J.M.W. Turner. The baton then passed to France where, in the hands of the impressionists, landscape painting became the vehicle for a revolution in Western painting (modern art) and the traditional hierarchy of the genres collapsed.

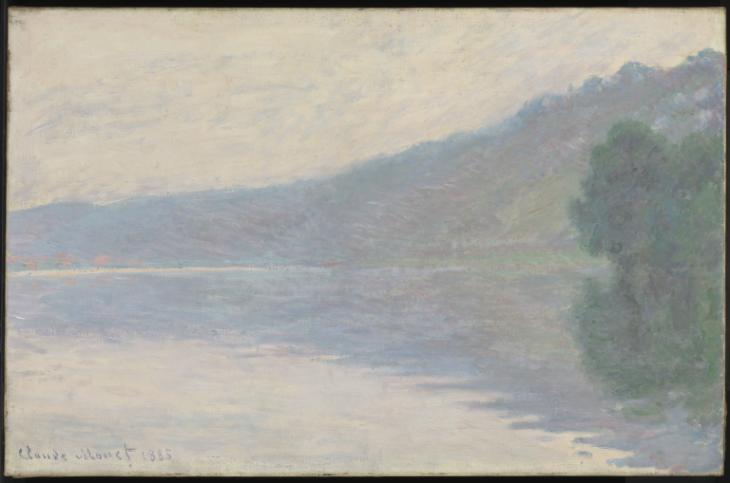

The Seine at Port-Villez 1894

Oil on canvas

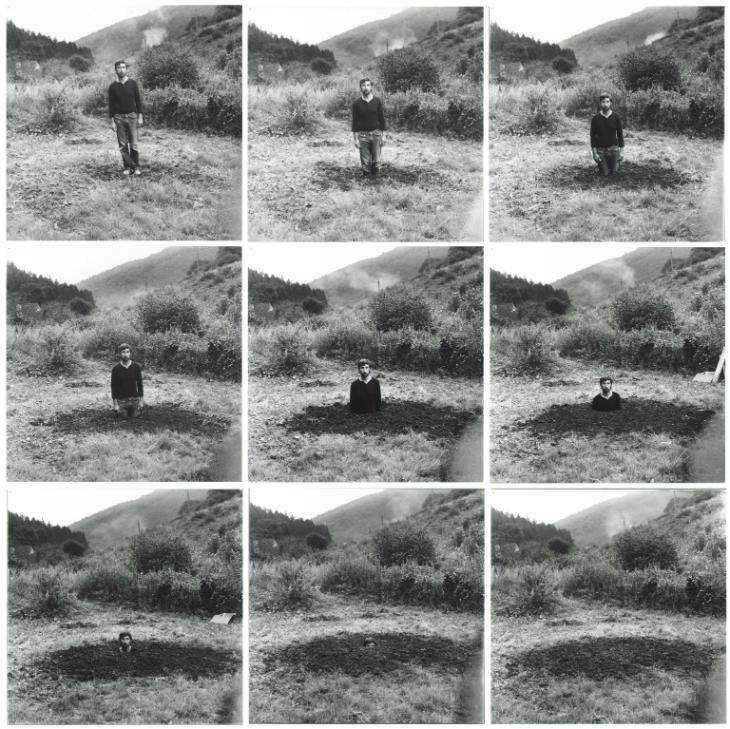

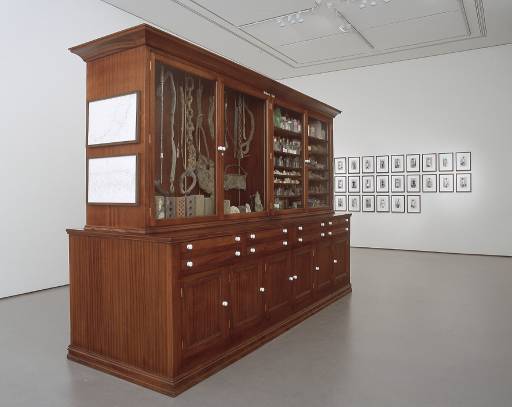

In the second half of the twentieth century, the definition of landscape was challenged. The genre expanded to include urban and industrial landscapes, and artists began to use less traditional media in the creation of landscape works. For example in the 1960s land artists such as Richard Long radically changed the relationship between landscape and art by creating artworks directly within the landscape.

Landscape continues to be a major theme in art with many artists using documentary techniques such as video, photography and classification processes to explore the ways we relate to the places we live in and to record the impact we have on the land and our environment..

The development of landscape

Explore the development of the landscape genre with our slideshow of key Tate artworks from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century, or use the links below to search these periods within Tate’s collection.

Further reading

Looking at the view

This thematic display looks at continuities in the way artists have framed our vision of the landscape over the past 300 years.

Art of the Garden

This exhibition which was at Tate Britain until August 2004, explores the impact of the garden on British art over the past two hundred years

Richard Long: Heaven and Earth

Find out how land artists in the 1960s began to radically re-think the relationship between landscape and art in this exhibition guide to Richard Long.

Artists in focus

J.M.W Turner and John Constable

The Valley Farm 1835

Oil on canvas

support: 1473 x 1251 mm

Presented by Robert Vernon 1847

Light and Colour (Goethe's Theory) - the Morning after the Deluge - Moses Writing the Book of Genesis exhibited 1843

Oil on canvas

support: 787 x 787 mm

frame: 1036 x 1036 x 115 mm

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Although considered to be rivals with notably different painting styles, J.M.W. Turner and John Constable changed the face of landscape painting in Britain. Both artists were influenced by romanticism, an artistic and literary movement of the late 1700s to mid-1800s which championed the expression of feeling and an interest in the natural world.

Many of Constable’s landscapes are of the Suffolk countryside close to his family home. He painted and sketched out-of-doors (en plein air) in order to get closer to nature and present a more realistic depiction of its details and the effects of light and the weather.

Turner on the other hand travelled extensively both within and outside of Britain painting dramatic seascapes and sublime landscapes which often had literary or historical references. Like Constable he was fascinated by the transient effects of light and weather. To Turner, light was the emanation of God’s spirit and he painted it with intensity using expressive brushwork to create shimmering landscapes which often appear almost abstract.

Introduction to J.M.W Turner

Read our introduction to this prolific landscape painter and browse videos, articles, learning activities and in-depth research publications about his work.

John Constable biography

Read our artist biography and see Constable artworks in Tate’s collection.

Graham Sutherland: An imaginative landscape

Black Landscape 1939-40

Oil and sand on canvas

support: 810 x 1321 mm

frame: 1006 x 1506 x 76 mm

Purchased 1980© The estate of Graham Sutherland

Graham Sutherland was a neo-romantic artist, who created rich, poetic and imaginative landscapes mainly inspired by Pembrokeshire in Wales. From 1941–1944 he was an official war artist, depicting the mining industry and the effects of bomb damage on the British landscape.

The precarious tension of opposites (happiness and unhappiness, beauty and ugliness)…can be interpreted according to the predilections and needs of the spectator with delight or horror…The painter is a kind of blotting paper; he soaks up impressions; he is very much part of the world.

Graham Sutherland

Graham Sutherland’s sketchbooks

Explore a digitised collection of forty sketchbooks and fragments of sketchbooks belonging to Sutherland, from 1935–1974.

Horned root forms in a landscape, from Sketchbook 4, 1944

Crayon on paper

© The estate of Graham Sutherland

View this item in Art & artists

Pink and black study of a winding road, with a bird in flight above, from Sketchbook 4, 1940–1944

Watercolour paint and ink on paper

© The estate of Graham Sutherland

View this item in Art & artists

Using a variety of materials such as graphite and watercolour, this sketchbook from 1940-1944 includes studies from the rolling hills and winding roads of Pembrokeshire alongside a sketch of some bomb damage to a lift-shaft.

Animating the Archives: Graham Sutherland

Watch the Animating the Archives video which looks at the conservation and digitisation of Graham Sutherland’s sketchbooks and the importance of archive collections to our understanding of artists’ practices.

Tate Archive 40 | 1980 Graham Sutherland ‘A Tragic Landscape’

Read our archive blog which discusses Sutherland’s preliminary sketch for Pastoral (1930), and how Sutherland was able to create images which conveyed the same sense of mystery and dramatic suspense of the Surrealists without ignoring visual reality or abandoning nature.

Paintings and Drawings by Graham Sutherland

This exhibition was on display in Tate Britain in 1953. Read the exhibition text, written by Sutherland, in which he describes his landscapes as paraphrases rather paintings directly from life.

Vija Celmins: Skies, seas and deserts

Galaxy 1975

Lithograph on paper

image: 317 x 418 mm

Purchased 1999© Vija Celmins

American artist Vija Celmins uses found photographs, often from scientific journals, as the source for her meticulous and mesmerising images of galaxies, seas and desert landscapes. Watch Celmins at work in her studio and find out about her ideas and processes:

Work of the Week: Galaxy by Vija Celmins

Read about what it is that draws Celmins to the texture of infinite landscapes in this blog article.

Celmins selects Turner

Celmins was invited to select works by J.M.W. Turner for this 2012 display at Tate Modern. Discover why this old master’s work inspires her.

Thinking drawing

Celmins discusses the development of her work in this interview for Tate Etc.

ARTIST ROOMS Vija Celmins learning resource

Explore the themes behind Celmins’s work and the processes and materials she uses in this online resource. Although written with teachers in mind, this resource is useful for anyone who would like to know more about the artist and her work.

Vija Celmins in Tate’s collection

See artworks by the artist in Tate’s collection.

Landscape in context

Watch curator Tim Batchelor discuss the 1650-1730 room at Tate Britain, a time when the restoration period introduced landscape painting as a new genre of art.

The detritus of the future and pleasure of the past

Critic and co-curator of Tate Britain’s Ruin Lust, Brian Dillion takes us through a chronological journey on artists fascination with ruins, from the seventeenth century to the present day.

Art maps: putting the Tate collection on the map

Tate meets Google maps. Browse art on the map or share your knowledge about locations.

Other perspectives

Gavin Pretor-Pinney, founder of the Cloud Appreciation Society, applies his cloud spotter’s eye to the Tate Collection.

The Edge of England

Poet Lavinia Greenlaw pens a poem on Constable inspired by a visit to the ruins of Hadleigh Castle, Kent.

River of dreams

Art historian John House and filmmaker Patrick Keiller talk about how London’s light has had an impact on the depiction of its river.

Ambient Landscape

Writer Martin Herbert looks at how artists and writers from the nineteenth century to the present day have depicted the loss of ruralism in England.

Contemporary British photographer Ingrid Pollard reflects on her artistic practice ‘in conversation’ with some key landscape works from Tate Britain’s collection displays.

Mind fields

Tate Etc. introduces eleven personal responses to artworks that reflect the changing face of British landscape, from 1811–1977.

Landscape in detail

A landscape of mortality

Read this essay which looks at landscape painter Paul Nash and how he depicted themes of mortality and spirit in his war inflicted landscapes.

The Art of the Sublime

Explore our online research publication which draws together the history of the sublime and the different ways the idea has been interpreted from the Baroque period to the present day, particularly in relation to the natural landscape.

Listen to this panel discussion on how landscape is portrayed in contemporary photography, from the creation of images that document man-made changes to our environment, to imagining worlds and views that range from the sublime, to the terrifying and ridiculous.

Related glossary terms

Picturesque, sublime, naturalism, plein air, romanticism, luminism, impressionism, neo-romanticism, land art, psychogeography