Mayday at the Pigeon Palace

This article appeared originally in the “Dispatch” section of the East Bay Review about a week ago. It fell off the internet (!) so I am delighted to have it reposted here. My friend Elizabeth Creely is the author, and she has also been a great supporter of our organizing efforts to save the Pigeon Palace.

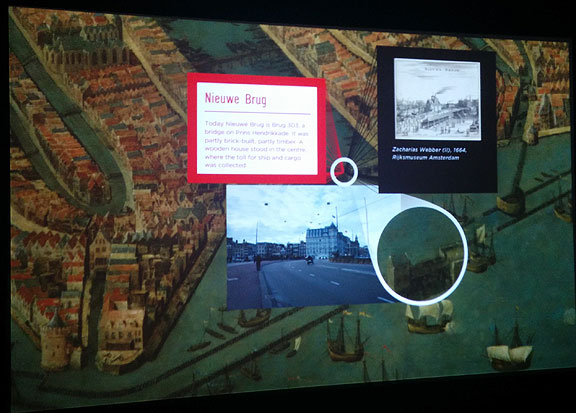

Real estate investors calculating profit margins on the potential purchase of the Pigeon Palace, May 5, 2015.

May 5, 2015: A man driving a gleaming SUV pulled over in front of an apartment building in San Francisco and let out a long, low whistle under his breath that was almost reverent. 2840 Folsom Street, a massive Victorian painted in shades of lemon yellow and chocolate brown, had banners made of bed sheets flying from every window. “Pigeon Palace 4 Ever,” read one. Another sheet, flapping and turning in the wind, read “Affordable Housing Forever.” These banners were made by the tenants of the Pigeon Palace, so-called because of the owner’s love of the birds. The building was for sale, and eviction was in the air. The current tenants had scheduled a protest that day to forestall the sale and forewarn any interested buyer that they would fight to stay in their homes.

The man parked his SUV and got out and walked over to look at the banners more closely. He looked expensive like his car: groomed silver hair, leather driving moccasins, and jeans which had been pressed. The look was a Wealthy Normcore, a low-key rendition of unstudied, luxurious ease. He stood under one of the banners, studying it. I walked over.

“Hi there,” I said. “Are you interested in buying this building?”

He looked at me. “Uh, no,” he replied. “I’m not interested.”

“No? How did you find out about this?” I gestured with my writing pad to the building.

“I was just driving by…” His words trailed off. He was mentally quitting the scene, having barely seen anything except the banners and their upstart proclamations.

“Can I get your name?” I asked.

“No,” he answered flatly. He turned on his heel and left.

The silver-haired man was probably lying. He was obviously there for a “walk-through”— a preliminary step in the eventual sale of a property. It had been scheduled that day by the state-appointed conservators of Frances Carati, the elderly landlord and owner of the property who had been declared incompetent to manage her own affairs a few years earlier by the county’s Adult Protective Services agency. She’s now living in a nursing home in San Francisco.

Frances’s father purchased the building in 1942 with his GI Bill for $12,000. Now it is worth at least $2 million. That’s the offer that was made by the San Francisco Community Land Trust, which had worked with the tenants of the building to purchase the Pigeon Palace. If the Land Trust’s offer had been accepted by the conservators, the tenants would have owned the building cooperatively and the Pigeon Palace would have been taken off the market. But the conservators didn’t accept the Land Trust’s offer and put the building on the auction block, citing their obligation to meet Frances Carati’s financial interests, which, they said, must be upheld. Two million wouldn’t cut it. The building must be sold and quickly. There would be more silver-haired men that day looking at the property, sizing up its dilapidated glory, balancing the cost of renovation against the profit it might produce, minus its current tenants.

Buyouts are the most common method for clearing a building. Low level harassment works, too. Real estate agents and speculators know that tenants will abandon their rights and their apartments, leaving them empty, ready for a quick coat of paint and maybe a new sink, before remerging on the rental market as a shiny dwelling available for $4,268.00, the median price of a two-bedroom apartment in the Mission District. I remember the elderly Latin American couple who lived down the street from me. The woman and I would greet each other equably on our way to the laundromat. “Hola,” we would murmur to each other in passing. One day, I noticed that the façade of their white stuccoed building was now a plastered a smooth slate-gray. The door to their apartment was gone. Under what conditions they’d been gotten rid off was anyone’s guess, but whether it was by preemptory command—you have to go now—or a buyout, the effect was the same. The couple had vanished, along with their door.

The tenants of the Pigeon Palace plan on staying put. As the silver-haired man sped away in his SUV, the tenants—Chris Carlsson, Adriana Camarena, Ed Wolf, Kirk Read, Keith Hennessy, and Carin McKay—were in their apartments, preparing to meet their friends and supporters outside to confront the buyers who wanted to buy the place.

Oscar Salinas was one of the first to arrive. He stood on the sidewalk reading a flyer; this was the Pigeon Manifesto, written by the tenants. It began: “Our six-unit building is called the Pigeon Palace, after the hearty rule-defying birds loved by our dear landlord Frances Carati. But oh shit! Our home is for sale! And the vultures are circling.”

Chris Carlsson, one of the tenants, walked down the steps. “Hey, there,” he said, walking over to Salinas. “Great to see you!”

“How you doing, buddy?” replied Salinas. The two men hugged.

Ian Waisler, a former tenant, walked up, smiling. “Hi,” he said to no one in particular. He sat down on the front stoop, a burrito in hand, and began eating it.

A man carrying a saxophone arrived, and looked around. “Where is everyone?” he asked. Ofir (that was his name) was a member of the Brass Liberation Orchestra, a “multigender/multiracial/multigenerational” musical group that provides a musical soundtrack for protests. He slung the saxophone around his neck and blew a few bluesy notes.

More people started arriving. I asked one them, Thom, why he was there. He hesitated. “Well…it’s simple,” he said finally. “I’m here to save my friends’ house. It’s that basic.” He looked relieved as he told me this.

Earlier, Chris had passed out a piece of paper with questions to pose to prospective buyers. “Do you know who lives here?” was one question. “What is your goal today?” was another. And “Can you imagine not evicting tenants?” The questions were simple and provocative and read like messages on a Jenny Holzer projection, designed to intervene in a process that was supposed to be smooth, unpublicized, and uneventful.

“This isn’t what people expect when they come to buy real estate,” observed the writer Rebecca Solnit, who had strolled up from the direction of 26th Street. “So I think it’s effective. But you know”—she turned her large eyes on me—“some people can create very elaborate rationales for evicting people.”

“Do you know what structure this is gonna be?” asked Thom. “Are we gonna stand around, Critical Mass style?” It would have been appropriate. Chris Carlsson is widely credited with starting Critical Mass, the monthly bike ride through the streets of San Francisco, although he flatly denies this.

Chris is a writer and the founder of Shaping San Francisco, a history project. (“History from below” is the purpose of the organization.) Chris and his co-tenants represent the now-vanishing culture of writers, artists and activists once native to America’s big cities and now becoming increasingly rare as San Francisco and New York host an influx of the wealthy, who seem intent on privatizing everything.

Privately held properties like the Pigeon Palace are not normally thought of as public space, but the distinction gets blurry when the tenants are masterful activists like Ed Wolf, a noted AIDS activist, or Adriana Camarena, founder of Unsettlers: Migrants, Homies and Mammas, a media project that investigates and chronicles the Mission District’s historic Latin American community. The Pigeon Palace became public space because of the activities that took place there. Small conventions of all sorts and for every reason made the apartments of the Pigeon Palace a public commons. Doors were open, dinners were made, plans discussed, visions brought forth. The city was shaped in the living rooms and kitchens of Pigeon Palace. The cheap rent birthed big ideas and projects: the artists, writers and activists who live at the Palace wrote books, edited anthologies, painted gorgeous murals, fought for health care during the AIDS crisis and, generally speaking, critically reflected San Francisco’s mythic past, muddled present, and vaunted future back out to the city. In a city where renters happily fork over 50 percent of their paycheck in order to live in a city enriched by ‘culture,’ people like Chris are being shown the door, while the work they did, which gave the city its identity as interesting and provocative place to live in, is both un-remunerated and monetized every time a real estate agent or development LLC refers to “vibrancy.” Your work here is finished, is the message. More »