Cockroaches are insects of the order Blattaria or Blattodea, of which about 30 species out of 4,500 total are associated with human habitations. About four species are well known as pests.[1][2]

Among the best-known pest species are the American cockroach, Periplaneta americana, which is about 30 millimetres (1.2 in) long, the German cockroach, Blattella germanica, about 15 millimetres (0.59 in) long, the Asian cockroach, Blattella asahinai, also about 15 millimetres (0.59 in) in length, and the Oriental cockroach, Blatta orientalis, about 25 millimetres (0.98 in). Tropical cockroaches are often much bigger, and extinct cockroach relatives and 'roachoids' such as the Carboniferous Archimylacris and the Permian Apthoroblattina were not as large as the biggest modern species.

The name cockroach comes from the Spanish word cucaracha, "chafer", "beetle", from cuca, "kind of caterpillar." The scientific name derives from the Latinized Greek name for the insect (Doric Greek: βλάττα, blátta; Ionic and Attic Greek: βλάττη, blátte'

The English form cockroach is a folk etymology reanalysis of the Spanish word into meaningful native parts, although cock referred to a rooster and a roach is a type of fish.

- Blattella germanica, German cockroach

- Blaptica dubia, South American/Peruvian Dubia cockroach

- Blatta orientalis, Oriental cockroach

- Blattella asahinai, Asian cockroach

- Blaberus craniifer, true death's head cockroach

- Blaberus discoidalis, discoid cockroach or false death's head

- Eurycotis floridana, Florida woods cockroach

- Gromphadorhina portentosa, Madagascar hissing cockroach

- laxta granicollis, Bark cockroach

- Parcoblatta pennsylvanica, Pennsylvania woods cockroach

- Periplaneta americana, American cockroach

- Periplaneta australasiae, Australian cockroach

- Periplaneta brunnea, black Mississippi cockroach

- Periplaneta fuliginosa, smokybrown cockroach

- Pycnoscelus surinamensis, Surinam cockroach

- Supella longipalpa, brown-banded cockroach

A 40–50 million year old cockroach in Baltic amber

|

A proposed phylogeny of the families.[3]

|

Mantodea, Isoptera, and Blattaria are usually combined by entomologists into a higher group called Dictyoptera. Current evidence strongly suggests that termites evolved directly from true cockroaches, and many authors now consider termites to be an epifamily of cockroaches,[4][5] as Blattaria excluding Isoptera is not a monophyletic group.[6]

Historically, the name Blattaria has been used largely interchangeably with the name Blattodea, and this name is used for the order by the current world catalogue, the Blattodea Species File Online. Another name, Blattoptera has come into use for this same paraphyletic group.[7] These earliest cockroach-like fossils ("Blattopterans" or "roachids") are from the Carboniferous period between 354–295 million years ago. However, these fossils differ from modern cockroaches in having long external ovipositors and are the ancestors of mantises as well as modern roaches. The first fossils of modern cockroaches with internal ovipositors appear in the early Cretaceous.

A bush cockroach (

Ellipsidion australe).

Cockroaches live in a wide range of environments around the world. Pest species of cockroaches adapt readily to a variety of environments, but prefer warm conditions found within buildings. Many tropical species prefer even warmer environments and do not fare well in the average household.

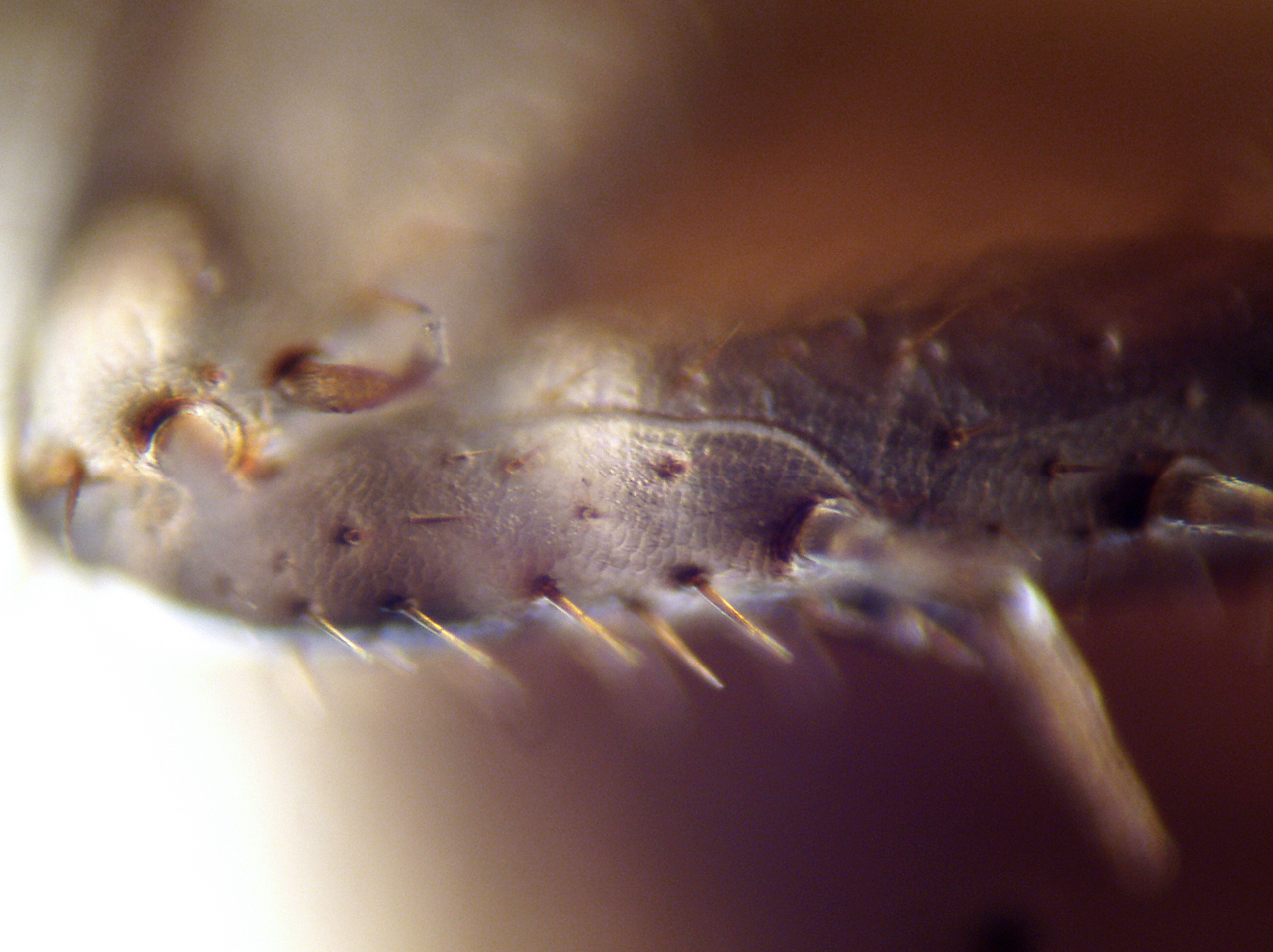

The spines on the legs were earlier considered to be sensory, but observations of their locomotion on sand and wire meshes have demonstrated that they help in locomotion on difficult terrain. The structures have been used as inspiration for robotic legs.[8][9]

Cockroaches leave chemical trails in their feces as well as emitting airborne pheromones for swarming and mating. These chemical trails transmit bacteria on surfaces.[citation needed] Other cockroaches will follow these trails to discover sources of food and water, and also discover where other cockroaches are hiding. Thus, cockroaches can exhibit emergent behavior,[10] in which group or swarm behavior emerges from a simple set of individual interactions.

Daily rhythms may also be regulated by a complex set of hormonal controls of which only a small subset have been understood. In 2005, the role of one of these proteins, Pigment Dispersing Factor (PDF), was isolated and found to be a key mediator in the circadian rhythms of the cockroach.[11]

Research has shown that group-based decision-making is responsible for complex behavior such as resource allocation. In a study where 50 cockroaches were placed in a dish with three shelters with a capacity for 40 insects in each, the insects arranged themselves in two shelters with 25 insects in each, leaving the third shelter empty. When the capacity of the shelters was increased to more than 50 insects per shelter, all of the cockroaches arranged themselves in one shelter. Researchers found a balance between cooperation and competition exists in the group decision-making behavior found in cockroaches. The models used in this research can also explain the group dynamics of other insects and animals.[10]

Cockroaches are mainly nocturnal[12] and will run away when exposed to light. A peculiar exception is the Asian cockroach, which is attracted to light. Another study tested the hypothesis that cockroaches use just two pieces of information to decide where to go under those conditions: how dark it is and how many other cockroaches there are. The study conducted by José Halloy and colleagues at the Free University of Brussels and other European institutions created a set of tiny robots that appear to the roaches as other roaches and can thus alter the roaches' perception of critical mass. The robots were also specially scented so that they would be accepted by the real roaches.[13]

Additionally, researchers at Tohoku University engaged in a classical conditioning experiment with cockroaches and discovered that the insects were able to associate the scent of vanilla and peppermint with a sugar treat.[14]

Cockroaches are generally rather large insects. Most species are about the size of a thumbnail, but several species are bigger. The world's heaviest cockroach is the Australian giant burrowing cockroach, which can reach 9 centimetres (3.5 in) in length and weigh more than 30 grams (1.1 oz). Comparable in size is the Central American giant cockroach Blaberus giganteus, which grows to a similar length but is not as heavy.

Cockroaches have a broad, flattened body and a relatively small head. They are generalized insects, with few special adaptations, and may be among the most primitive living neopteran insects. The mouthparts are on the underside of the head and include generalised chewing mandibles. They have large compound eyes, two ocelli, and long, flexible, antennae.

The first pair of wings (the tegmina) are tough and protective, lying as a shield on top of the membranous hind wings. All four wings have branching longitudinal veins, and multiple cross-veins. The legs are sturdy, with large coxae and five claws each. The abdomen has ten segments and several cerci.[15]

Female cockroaches are sometimes seen carrying egg cases on the end of their abdomen; the egg case of the German cockroach holds about 30 to 40 long, thin eggs, packed like frankfurters in the case called an ootheca. The egg capsule may take more than five hours to lay and is initially bright white in color. The eggs are hatched from the combined pressure of the hatchlings gulping air. The hatchlings are initially bright white nymphs and continue inflating themselves with air, becoming harder and darker within about four hours. Their transient white stage while hatching and later while molting has led many to claim the existence of albino cockroaches.

A female German cockroach carries an egg capsule containing around 40 eggs. She drops the capsule prior to hatching, though live births do occur in rare instances. Development from eggs to adults takes 3 to 4 months. Cockroaches live up to a year. The female may produce up to eight egg cases in a lifetime; in favorable conditions, she can produce 300 to 400 offspring. Other species of cockroach, however, can produce an extremely high number of eggs in a lifetime; in some cases a female needs to be impregnated only once to be able to lay eggs for the rest of her life.

Aside from the famous hissing noise, some cockroaches (including a species in Florida) will make a chirping noise.[16]

Cockroaches are most common in tropical and subtropical climates. Some species are in close association with human dwellings and widely found around garbage or in the kitchen. Cockroaches are generally omnivorous with the exception of the wood-eating species such as Cryptocercus; these roaches are incapable of digesting cellulose themselves, but have symbiotic relationships with various protozoans and bacteria that digest the cellulose, allowing them to extract the nutrients.

The similarity of these symbionts in the genus Cryptocercus to those in termites are such that it has been suggested that they are more closely related to termites than to other cockroaches,[17] and current research strongly supports this hypothesis of relationships.[18] All species studied so far carry the obligate mutualistic endosymbiont bacterium Blattabacterium, with the exception of Nocticola australiensise, an Australian cave dwelling species without eyes, pigment or wings, and which recent genetic studies indicates are very primitive cockroaches.[19][20]

Nymph of a cockroach, 3 mm in length.

Cockroaches, like all insects, breathe through a system of tubes called tracheae. The tracheae of insects are attached to the spiracles, excluding the head. Thus cockroaches, like all insects, are not dependent on the mouth and windpipe to breathe. The valves open when the CO2 level in the insect rises to a high level; then the CO2 diffuses out of the tracheae to the outside and fresh O2 diffuses in. Unlike in vertebrates that depend on blood for transporting O2 and CO2, the tracheal system brings the air directly to cells, the tracheal tubes branching continually like a tree until their finest divisions, tracheoles, are associated with each cell, allowing gaseous oxygen to dissolve in the cytoplasm lying across the fine cuticle lining of the tracheole. CO2 diffuses out of the cell into the tracheole.

While cockroaches do not have lungs and thus do not actively breathe in the vertebrate lung manner, in some very large species the body musculature may contract rhythmically to forcibly move air out and in the spiracles; this may be considered a form of breathing.[21]

Cockroaches use pheromones to attract mates, and the males practice courtship rituals such as posturing and stridulation. Like many insects, cockroaches mate facing away from each other with their genitalia in contact, and copulation can be prolonged. A few species are known to be parthenogenetic, reproducing without the need for males.[15]

The female usually attaches the egg-case to a substrate, inserts it into a suitably protective crevice, or carries it about until just before the eggs hatch. Some species, however, are ovoviviparous, keeping the eggs inside their bodies, with or without an egg-case, until they hatch. At least one genus, Diploptera is fully viviparous.[15]

Cockroach nymphs are generally similar to the adults, except for undeveloped wings and genitalia. Development is generally slow, and may take anywhere from a few months to over a year. The adults are also long-lived, and have been recorded as surviving for four years in the laboratory.[15]

Cockroaches are among the hardiest insects on the planet. Some species are capable of remaining active for a month without food and are able to survive on limited resources like the glue from the back of postage stamps.[22] Some can go without air for 45 minutes. In one experiment, cockroaches were able to recover from being submerged underwater for half an hour.[23]

It is popularly suggested that cockroaches will "inherit the earth" if humanity destroys itself in a nuclear war. Cockroaches do indeed have a much higher radiation resistance than vertebrates, with the lethal dose perhaps 6 to 15 times that for humans. However, they are not exceptionally radiation-resistant compared to other insects, such as the fruit fly.[24]

The cockroach's ability to withstand radiation better than human beings can be explained through the cell cycle. Cells are most vulnerable to the effects of radiation when they are dividing. A cockroach's cells divide only once each time it molts, which is weekly at most in a juvenile roach. Since not all cockroaches would be molting at the same time, many would be unaffected by an acute burst of radiation, but lingering radioactive fallout would still be harmful.[25]

Cockroaches are one of the most commonly noted household pest insects.[26] They feed on human and pet food, and can leave an offensive odor.[27] They can also passively transport microbes on their body surfaces including those that are potentially dangerous to humans, particularly in environments such as hospitals.[28][29] Cockroaches have been shown to be linked with allergic reactions in humans.[30][31] One of the proteins that triggers allergic reactions has been identified as tropomyosin.[32] These allergens have also been found to be linked with asthma.[33]

General preventive measures against household pests include keeping all food stored away in sealed containers, using garbage cans with a tight lid, frequent cleaning in the kitchen, and regular vacuuming. Any water leaks, such as dripping taps, should also be repaired. It is also helpful to seal off any entry points, such as holes around baseboards, in between kitchen cabinets, pipes, doors, and windows with some steel wool or copper mesh and some cement, putty or silicone caulk.

Diatomaceous earth applied as a fine powder works very well to eliminate cockroaches as long as it remains in place and dry. Diatomaceous earth is harmless to humans and feels like talcum powder. Most insects, including bed bugs, are vulnerable to it.

Some cockroaches have been known to live up to three months without food and a month without water. Frequently living outdoors, although preferring warm climates and considered "cold intolerant," they are resilient enough to survive occasional freezing temperatures. This makes them difficult to eradicate once they have infested an area.

There are numerous parasites and predators of cockroaches, but few of them have proven to be highly effective for biological control of pest species. Wasps in the family Evaniidae are perhaps the most effective insect predators, as they attack the egg cases, and wasps in the family Ampulicidae are predators on adult and nymphal cockroaches (e.g., Ampulex compressa). The house centipede is probably the most effective control agent of cockroaches, though many homeowners find the centipedes themselves objectionable.

Ampulex wasps sting the roach more than once and in a specific way. The first sting is directed at nerve ganglia in the cockroach's thorax; temporarily paralyzing the victim for 2–5 minutes, which is more than enough time for the wasp to deliver a second sting. The second sting is directed into a region of the cockroach's brain that controls the escape reflex, among other things.[34] When the cockroach has recovered from the first sting, it makes no attempt to flee. The wasp clips the antennae with its mandibles and drinks some of the hemolymph before walking backwards and dragging the roach by its clipped antennae to a burrow, where an egg will be laid upon it. The wasp larva feeds on the subdued, living cockroach.

Bait stations, gels containing hydramethylnon or fipronil, as well as boric acid powder, are toxic to cockroaches.[35] Baits with egg killers are also quite effective at reducing the cockroach population. Additionally, pest control products containing deltamethrin or pyrethrin are very effective.[35]

In Singapore and Malaysia, taxi drivers use Pandan leaves as a cockroach repellent in their vehicles.[36]

An inexpensive roach trap can easily be made from a deep smooth-walled jar with some roach food inside, placed with the top of the jar touching a wall or with sticks leading up to the top, so that the roaches can reach the opening. Once inside, they cannot climb back out. An inch or so of water or stale beer (by itself a roach attractant) will ensure they drown. The method works well with the American cockroach but less so with the German cockroach.[37] A bit of Vaseline can be smeared on the inside of the jar to enhance slipperiness. The method is sometimes called the "Vegas roach trap" after it was popularized by a Las Vegas-based TV station. This version of the trap uses coffee grounds and water.[38]

Some of the earliest writings about cockroaches encouraged their use as medicine. Pedanius Dioscorides (1st century), Abu Hanifa ad-Dainuri (9th century), and Kamal al-Din al-Damiri (14th century ) all offered medicines that either suggest grinding them up with oil or boiling them, and Lafcadio Hearn claimed[39] that in the 1870s many New Orleanians had great faith in a remedy of boiled cockroach tea.

Because of their long, persistent association with humans, cockroaches are frequently referred to in art, literature, folk tales and theater and film and real life. In Western culture, cockroaches are often depicted as vile and dirty pests. Their size, long antennae, shiny appearance and spiny legs make them disgusting to many humans, sometimes even to the point of phobic responses.[40][41] This is borne out in many depictions of cockroaches, from political versions of the song La Cucaracha where political opponents are compared to cockroaches, through the 1982 movie Creepshow and TV shows such as the X-Files, to the Hutu extremists' reference to the Tutsi minority as cockroaches during the Rwandan Genocide in 1994 and the controversial cartoons published in the "Iran weekly magazine" in 2006 which implied a comparison between Iranian Azeris and cockroaches. The second part of the Harry Hole crime novels written by Jo Nesbø is called The Cockroaches (Kakerlakkene in Norwegian). In the movie Men in Black a giant alien cockroach is shown as a predator who eats a farmer and then uses his skin to disguise itself as a human being. In Oliver Twist, the children, Mr. Bumble, and Widow Corney sing about feeding Oliver cockroaches in a canister. Award-winning computer and video game series Fallout takes place in a post-Atom bomb war universe, in which enlarged, irradiated cockroaches are present as early enemies. This is a nod to the notion of their nuclear fortitude. Also, in Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis, a man, Gregor, is transformed overnight into a monstrous insect with cockroach-like features. He views himself as repulsive in his new identity. Ayn Rand in her early novel "We the Living" compared the Soviet Union to a huge pile of cockroaches. During Australian Rugby League State of Origin matches it is common slang to refer to Queensland as canetoads and New South Wales as cockroaches.

Not all depictions of cockroaches are purely negative, however. Twilight of the Cockroaches depicts the extermination of cockroaches as a holocaust, and presents a happy ending as the pregnant lead cockroach, Naomi, escapes to mother many generations. In the Pixar film Wall-E, a cockroach that has survived all humanity is the best friend of the lead character (a robot), and waits patiently on him to return. The same cockroach survives getting squished twice. In the film Joe's Apartment, the cockroaches help the titular hero, and the narrator of the book archy and mehitabel is a sympathetic cockroach. In the book Revolt of the Cockroach People, an autobiographical novel by Oscar Zeta Acosta, cockroaches are used as a metaphor for oppressed and downtrodden minorities in US society in the 1960s and 70s. The image of cockroaches as resilient also leads people to compare themselves to cockroaches. Madonna has famously quoted, "I am a survivor. I am like a cockroach, you just can't get rid of me."[42] "Cockroach", or some variant of it is also used as a nickname, for example Boxing coach Freddie Roach, who was nicknamed La Cucaracha (The Cockroach) when he was still competing as a fighter. The album The Lonesome Crowded West by rock group Modest Mouse features a song with the title and lyric "Doin' The Cockroach". In the Netherlands 'Zaza the cockroach' becomes a buddy of the boy called Pluk in a popular Dutch book for children: 'Pluk van de Petteflet', written by Annie M.G. Schmidt. In Suzanne Collins's Underland Chronicles series, giant cockroaches are allies of humans in the Underland, and they and a toddler named Margaret (a.k.a. Boots, or "the princess," as the cockroaches call her) love each other.

- ^ Valles, SM; Koehler, PG; Brenner, RJ. (1999). "Comparative insecticide susceptibility and detoxification enzyme activities among pestiferous blattodea". Comp Infibous Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol 124 (3): 227–232. DOI:10.1016/S0742-8413(99)00076-6. PMID 10661713.

- ^ Schal, C; Hamilton, R. L. (1990). "Integrated suppression of synanthropic cockroaches". Annu. Rev. Entomol 35: 521–551. DOI:10.1146/annurev.en.35.010190.002513. PMID 2405773. http://www4.ncsu.edu/~coby/schal/1990SchalAREreview.pdf.

- ^ Maekawa K., Kiyoto; Matsumoto T. (2000). "Molecular phylogeny of cockroaches (Blattaria) based on mitochondrial COII gene sequences". Systematic Entomology 25 (4): 511–519. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3113.2000.00128.x.

- ^ "Termites are 'social cockroaches'". BBC News. 13 April 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/6553219.stm.

- ^ Eggleton, P. (2007), Biological Letters, June 7, cited in Science News vol. 171, p. 318

- ^ Termites are 'social cockroaches' news.bbc.co.uk, April 13, 2007

- ^ Grimaldi, D (1997): A fossil mantis (Insecta: Mantoidea) in Cretaceous amber of New Jersey, with comments on early history of Dictyoptera. American Museum Novitates 3204: 1–11

- ^ Ritzmann, Roy E.; Quinn, Roger D.; Fischer, Martin S. (2004). "Convergent evolution and locomotion through complex terrain by insects, vertebrates and robots". Arthropod Structure & Development 33 (3): 361–379. DOI:10.1016/j.asd.2004.05.001. http://www.case.edu/artsci/biol/ritzmann/Ritzmann%204.pdf.

- ^ Spagna, J C; Goldman, D I; Lin, P-C; Koditschek, D E; Full, Robert J (2007). "Distributed mechanical feedback control of rapid running on challenging terrain". Bioinspir Biomim 2 (1): 9–18. DOI:10.1088/1748-3182/2/1/002. PMID 17671322.

- ^ a b Jennifer Viegas. "Cockroaches Make Group Decisions". Discovery Channel. http://animal.discovery.com/news/briefs/20060327/cockroach.html. Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ^ Hamasaka, Yasutaka; Mohrherr, CJ; Predel, R; Wegener, C (22). "Chronobiological analysis and mass spectrometric characterization of pigment-dispersing factor in the cockroach Leucophaea maderae". The Journal of Insect Science 5 (43): 43. PMC 1615250. PMID 17119625. //www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1615250.

- ^ University of California Integrated Pest Management Program. Ipm.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved on 2012-04-29.

- ^ Lemonick, Michael D. (2007-11-15). "Robotic Roaches Do the Trick". Time Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1684427,00.html?imw=Y.

- ^ Wynne Parry. "Pavlovian Cockroaches Learn Like Dogs (and Humans)". Discover Magazine. http://discovermagazine.com/2007/sep/pavlovian-cockroaches-learn-like-dogs-and-humans. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ a b c d Hoell, H.V., Doyen, J.T. & Purcell, A.H. (1998). Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity, 2nd ed.. Oxford University Press. pp. 362–364. ISBN 0-19-510033-6.

- ^ CockRoach (Blattella Germanica). Archived 8 August 2011 at WebCite pest911.com

- ^ Eggleton, P. (2001). "Termites and trees: a review of recent advances in termite phylogenetics". Insectes Sociaux 48 (3): 187–193. DOI:10.1007/PL00001766.

- ^ Lo, N.; Bandi, C; Watanabe, H; Nalepa, C; Beninati, T (2003). "Evidence for Cocladogenesis Between Diverse Dictyopteran Lineages and Their Intracellular Endosymbionts". Molecular Biology and Evolution 20 (6): 907–13. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msg097. PMID 12716997. http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/20/6/907.pdf. Archived 8 August 2011 at WebCite

- ^ Cave may hold missing link. Theage.com.au (2007-03-21). Retrieved on 2012-04-29.

- ^ Lo, N; Beninati, T; Stone, F; Walker, J; Sacchi, L (2007). "Cockroaches that lack Blattabacterium endosymbionts: The phylogenetically divergent genus Nocticola". Biology letters 3 (3): 327–30. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0614. PMC 2464682. PMID 17376757. //www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2464682.

- ^ The Cockroach FAQ Archived 8 August 2011 at WebCite bio.umass.edu

- ^ Mullen, Gary; Lance Durden, Cameron Connor, Daniel Perera, Lynsey Little, Michael Groves and Rebecca Erskine (2002). Medical and Veterinary Entomology. Amsterdam: Academic Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-12-510451-0.

- ^ MythBusters – Drowning Cockroaches?. YouTube (2008-07-23). Retrieved on 2012-04-29.

- ^ "Cockroaches & Radiation". http://www.abc.net.au/science/k2/moments/s1567313.htm. Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ^ Joseph G. Kunkel. "Are cockroaches resistant to radiation?". http://www.bio.umass.edu/biology/kunkel/cockroach_faq.html#Q5. Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ^ "How to Get Rid of Cockroaches". Bill Larsen. http://summitpestmanagement.com/how_to_get_rid_of_roaches.php. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Brenner, R.J.; Koehler, P.; Patterson, R.S. (1987). "Health Implications of Cockroach Infestations". Infestations in Med 4 (8): 349–355.

- ^ Rivault, C.; Cloarec, A.; Guyader, A. Le (1993). "Bacterial load of cockroaches in relation to urban environment". Epidemiology and Infection 110 (2): 317–325. DOI:10.1017/S0950268800068254. PMC 2272268. PMID 8472775. //www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2272268.

- ^ Elgderi, RM; Ghenghesh, KS; Berbash, N. (2006). "Carriage by the German cockroach (Blattella germanica) of multiple-antibiotic-resistant bacteria that are potentially pathogenic to humans, in hospitals and households in Tripoli, Libya". Ann Trop Med Parasitol 100 (1): 55–62. DOI:10.1179/136485906X78463. PMID 16417714.

- ^ Bernton, H.S.; Brown, H. (1964). "Insect Allergy Preliminary Studies of the Cockroach". J. Allergy 35 (506–513): 506–13. PMID 14226309.

- ^ Kutrup, B (2003). "Cockroach Infestation in Some Hospitals in Trabzon, Turkey". Turk. J. Zool. 27: 73–77. http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/issues/zoo-03-27-1/zoo-27-1-12-0005-1.pdf.

- ^ Santos, AB; Chapman, MD; Aalberse, RC; Vailes, LD; Ferriani, VP; Oliver, C; Rizzo, MC; Naspitz, CK et al. (1999). "Cockroach allergens and asthma in Brazil: identification of tropomyosin as a major allergen with potential cross-reactivity with mite and shrimp allergens". J Allergy Clin Immunol 104 (2): 329–337. DOI:10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70375-1. PMID 10452753.

- ^ Kang, B; Vellody, D; Homburger, H; Yunginger, JW (1979). "Cockroach cause of allergic asthma. Its specificity and immunologic profile". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 63 (2): 80–86. DOI:10.1016/0091-6749(79)90196-9. PMID 83332.

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- ^ a b "Cockroaches". Alamance County Department of Environmental Health. http://www.alamance-nc.com/Alamance-NC/Departments/Environmental+Health/Environmental+Hazards/Cockroaches.htm. Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- ^ Li J. and Ho S.H. Pandan leaves (Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb.) As A Natural Cockroach Repellent. Proceedings of the 9th National Undergraduate Research Opportunites Programme (2003-09-13).

- ^ William Brodbeck Herms. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. The MacMillan company, 1915, p. 44.

- ^ Inexpensive Cockroach Trap Proving More Effective Than Sprays – KVBC, Las Vegas, June 27, 2006.

- ^ Quoted in The Eat-A-Bug Cookbook p. 66

- ^ Berle, D. (2007). "Graded Exposure Therapy for Long-Standing Disgust-Related Cockroach Avoidance in an Older Male". Clinical Case Studies 6 (4): 339. DOI:10.1177/1534650106288965.

- ^ Botella, C.M.; Juan, M.C.; Baños, R.M.; Alcañiz, M.; Guillén, V.; Rey, B. (2005). "Mixing Realities? An Application of Augmented Reality for the Treatment of Cockroach Phobia". CyberPsychology & Behavior 8 (2): 162. DOI:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.162.

- ^ "I am a survivor. I am like a cockroach, you just can't get rid of me." – Madonna. Thinkexist.com. Retrieved on 2012-04-29.

- Cockroaches: Ecology, Behavior, and Natural History, by William J. Bell, Louis M. Roth, and Christine A. Nalepa, ISBN 0-8018-8616-3, 2007

- Firefly Encyclopedia of Insects and Spiders, edited by Christopher O'Toole, ISBN 1-55297-612-2, 2002

- Insects: Their Biology and Cultural History, Bernhard Klausnitzer, ISBN 0-87663-666-0, 1987

Entries at the University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Featured Creatures Web site: