Abbiateci, A., Arsonists in Eighteenth-Century France, in Foster, R., Ranum, O. (Eds), Deviants and the Abandoned in French Society, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins UP, 1978 pp. 157-179.

Abbiateci, A., Les incendiaries devant le Parlement de Paris: Essai de Typologie Criminelle (XVIIIe siècle), in Abbiateci, A. (Ed.), Crimes et Criminalité en France sous l’Ancien Régime, XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles, Paris, Colin, 1971, pp. 13-32.

Adam, T., Blickle, P., (Eds), Bundschuh: Untergrombach 1502, das unruhige Reich und die Revolutionierbarkeit Europas, Stuttgart, Steiner, 2004.

Ammerer, G., Heimat Straße. Vaganten im Österreich des Ancien Régime, Wien, Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, 2003.

Avé-Lallemant, F. C. B., Das deutsche Gaunerthum in seiner sozialpolitischen, literarischen und linguistischen Ausbildung zu seinem heutigen Bestande, 3 vols., Leipzig, Brockhaus, 1858-1862.

Baumann, R., Landsknechte, Munich, Beck, 1994.

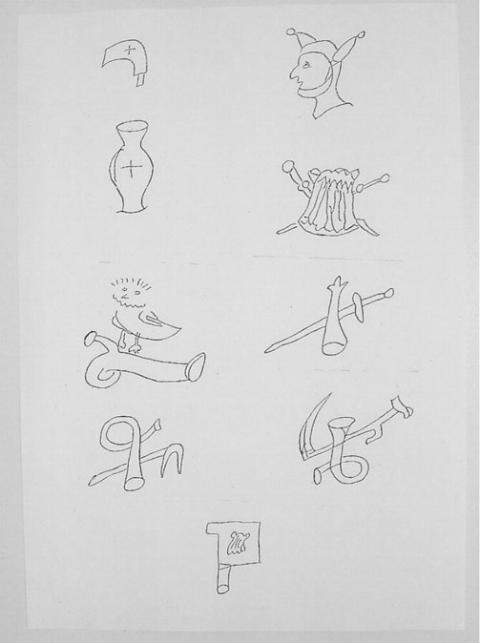

Bechstein, L., Die Mordbrenner zur Zeit des deutschen Krieges und deren Zeichen, in Bechstein, L. (Ed.), Deutsches Museum für Geschichte, Literatur, Kunst und Alterthumsforschung, 2 vols., Jena, Mauke, 1842/43, reprint Hildesheim, Olms 1973, pp. 309-320.

Behringer, W., Der Abwickler der Hexenforschung im Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA): Günther Franz, in Bauer, D. et al. (Eds), Himmler Hexenkartothek, Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld, 1999, pp. 109-134.

Behringer, W., Geschichte der Hexenforschung, in Sönke, L., Schmidt, J.-M. (Eds), Wider alle Hexerei und Teufelswerk. Die europäische Hexenverfolgung und ihre Auswirkungen auf Südwestdeutschland, Thorbecke, Ostfildern, 2004, pp. 485-668.

Blickle, P., Kommunalismus, 2 vols., Munich, Oldenbourg, 2000.

Delumeau, J., Angst im Abendland, Reinbek bei Hamburg, Rowohlt, 1989.

Dillinger, J., «Böse Leute». Hexenverfolgungen in Schwäbisch-Österreich und Kurtrier im Vergleich, Trier, Paulinus, 1999.

Dillinger, J.,Freiburgs Bundschuh, Zeitschrift für historische Forschung, 2005, 32, pp. 407-435.

Dillinger, J., Terrorists and Witches: Popular Ideas of Evil in the Early Modern Period, History of European Ideas, 2004, 30, pp. 167-182.

Dolan, F., Ashes and ‘the Archive’: The London Fire of 1666, Partisanship, and Proof, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, 2001, 31, 2, pp. 379-408.

Fiedler, S., Kriegswesen und Kriegführung im Zeitalter der Landsknechte, Koblenz, Bernard & Graefe, 1985.

Franz, G., Der deutsche Bauernkrieg, 12th edition, Darmstadt, WGB, 1984.

Fritz, G., Räuberbanden und Polizeistreifen. Der Kampf zwischen Kriminalität und Staatsgewalt im Südwesten des Alten Reiches zwischen 1648 und 1806, Remshalden, Manfred Hennecke Verlag, 2003.

Fritz, T., Hexenverfolgungen in der Reichsstadt Reutlingen, in Dillinger, J., Fritz, T., Mährle, W. (Eds), Zum Feuer verdammt, Stuttgart, Steiner, 1998, pp. 163-324.

Geremek, B., Les fils de Caïn. L’image des pauvres et des vagabonds dans la littérature européenne du XVe au XVIIe siècle, Paris, Flammarion,1991.

Geremek, B., Les marginaux parisiens aux XIVe et XVe siècles, Paris, Flammarion, 1976.

Ginzburg, C., Ecstasies. Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath, New York, Penguin, 1992.

Grassberger, R., Die Brandlegungskriminalität, Wien, Springer, 1928.

Graus, F., Organisationsformen der Randständigen. Das sogenannte Königreich der Bettler, in Gilomen, H.-P., Moraw, P., Schwinges, R. (Eds), Frantisek Graus: Ausgewählte Aufsätze (1959-1989), Stuttgart, Thorbecke 2002, pp. 351-368.

Guazzo, F., Compendium Maleficarum, (Original: Milan 1608), Summers, M. (Ed.), New York, Dover, 2nd ed. 1988.

Gueniffey, P., La politique de la Terreur. Essai sur la violence révolutionnaire, Paris, Fayard, 2000.

Hartung, W., Die Spielleute. Eine Randgruppe in der Gesellschaft des Mittelalters, Wiesbaden, Steiner, 1982.

Helleiner, K.‚ Brandstiftung als Kriegsmittel, Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, 1930, 20, pp. 326-349

Hellwig, A., Brandstiftungen aus Aberglauben, Monatsschrift für Kriminalpsychologie und Strafrechtsreform, 1910, 6, pp. 500-506.

Heydenreuter, R. (Ed.), «Gott zur Ehr, dem Nächsten zur Wehr»: Zur Geschichte der Feuerwehr in Bayerisch-Schwaben, Munich, Generaldirektion der staatlichen Archive Bayerns, 2000.

Hiro, D., War without End, London, Routledge, 2002.

Hobsbawm, E., Captain Swing, 2nd ed. New York, Norton, 1975.

Hoffman, B., Inside Terrorism, New York, Columbia U.P., 1998.

Irsigler, F., Lassotta, A., Bettler und Gaukler, Dirnen und Henken. Randgruppen und Außenseiter in Köln 1300-1600, Köln, Greven, 1984.

Jenkins, P., Images of Terror, Yew York, Aldine de Gruyter, 2003.

Jones, E. L., Porter, S., Turner, M., A Gazetteer of English Urban Fire Disasters, 1500-1900, Norwich, Geo Books, 1984.

Jütte, R., Abbild und soziale Wirklichkeit des Bettler- und Gaunertums zu Beginn der Neuzeit. Sozial- mentalitäts- und sprachgeschichtliche Studien zum Liber Vagatorum (1510), Cologne, Böhlau, 1988.

Jütte, R., Arme, Bettler, Beutelschneider. Eine Sozialgeschichte der Armut, Weimar, Böhlau, 2000.

Kästle, H., Brandstiftung: Erkennen, Aufklären, Verhüten, Stuttgart, Boorberg, 1992.

Köhn, R., Der Bundschuh von 1517, in Adam, T., Blickle, P., (Eds), Bundschuh: Untergrombach 1502, das unruhige Reich und die Revolutionierbarkeit Europas, Stuttgart, Steiner, 2004, pp. 122-138.

Kramer, K.-S., Grundriß einer rechtlichen Volkskunde, Göttingen, Schwartz, 1974.

Lefebvre, G., La Grande Peur de 1789, 3ème édition, Paris, Colin, 1988.

Metzger, H.-D., Heiden, Juden oder Teufel? Millenniarismus und Indianermission in Massachusetts 1630-1700’ Geschichte und Gesellschaft, 2001, 27, pp. 118-148.

Monter, W., Witchcraft in France and Switzerland, Ithaca, Cornell U.P., 1976.

Naphy, W., Plagnes, Poisons and Potions, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2002.

Po-Chia Hsia, R.,The Myth of Ritual Murder: Jews and Magic in Reformation Germany, New Haven, Yale U.P., 1988.

Ramsay, C., The Ideology of the Great Fear, Johns Hopkins UP, Baltimore, 1992.

Reyscher, A. L. (Ed.), Vollständige, historisch und kritisch bearbeitete Sammlung der württembergischen Gesetze, 29 vols.,Tübingen, Cotta, 1828-1851.

Roberts, P., Arson, Conspiracy and Rumour in Early Modern Europe, Continuity and Change, 1997, 12, pp. 9-20.

Roeck, B., Außenseiter, Randgruppen, Minderheiten, Göttingen, Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, 1993.

Rosenkranz, A., Der Bundschuh. Die Erhebung des südwestdeutschen Bauernstandes in den Jahren 1493-1517, 2 vols., Heidelberg, Winter, 1927.

Schild, W., Die Dimensionen der Hexerei: Vorstellung-Begriff-Verbrechen-Phantasie, in Lorenz, S. et al. (Eds), Wider alle Hexerei und Teufelswerk. Die europäische Hexenverfolgung und ihre Auswirkungen auf Südwestdeutschland, Ostfildern, Thorbecke, 2004, pp. 1-104.

Schubert, E., Fahrendes Volk im Mittelalter, Bielefeld: Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, 1995.

Schulte, R., Feuer im Dorf, in Reif, H. (Ed.), Räuber, Volk und Obrigkeit. Studien zur Geschichte der Kriminalität in Deutschland seit dem 18. Jahrhundert, Frankfurt a. M, Suhrkamp, 1984, pp. 100-152.

Schwerhoff, G., Aktenkundig und gerichtsnotorisch. Einführung in die Historische Kriminalitätsforschung, in Historische Einführungen, vol. 3, Tübingen, Diskord,1999, pp. 61-68.

Scott, T., Freiburg and the Breisgau, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1986.

Scott, T., «Nichts denn die Gerechtigkeit Gottes» Jos Fritz und der Bundschuh, in Haumann, H., Schadek, H. (Eds), Geschichte der Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau, 3 vols., 2nd edition, Stuttgart: Theiss 2001, 2, pp. 28-35.

Scotti, J.J. (Ed.), Sammlung der Gesetze und Verordnungen welche in dem vormaligen Churfürstenthm Trier über Gegenstände der Landeshoheit, Verfassung, Verwaltung und Rechtspflege ergangen sind, 3 vols., Düsseldorf, Wolf, 1832.

Scribner, B., The Mordbrenner Fear in Sixteenth-Century Germany: Political Paranoia or the Revenge of the Outcast? In The German Underworld. Deviants and Outcasts in German History, ed. Richard Evans, London, Routledge, 1988, pp. 29-56.

Spicker-Beck, M., Mordbrennerakten: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Analyse von Folterprozessen des 16. Jahrhunderts, in Häberlein, M. (Ed.), Devianz, Widerstand und Herrschaftspraxis in der Vormoderne: Studien zu Konflikten im südwestdeutschen Raum (15.-18. Jahrhundert), Konstanz, UVK, 1999, pp. 53-66.

Spicker-Beck, M., Räuber, Mordbrenner, umschweifendes Gesind, Freiburg i.B., Rombach, 1995.

Repertorium der Policeyordnungen der Frühen Neuzeit ed. Härter K., Stolleis M., 5 vols, Frankfurt, Klostermann 1996-2004.

Timcke, G., Der Straftatbestand der Brandstiftung in seiner Entwicklung durch die Wissenschaft des Gemeinen Strafrechts, Göttingen, Typoscript, 1965.

Underdown, D., Fire from Heaven, New Haven, Yale UP, 1992.

Ventzke, M., Fürsten als Feuerbekämper, in Ventzke, M. (Ed.), Hofkultur und aufklärerische Reformen in Thüringen, Cologne, Böhlau, 2002, pp. 223-235.

Wucke, B., Gebrochen ist des Feuers Macht: Ein Abriß zur Geschichte der Feuerwehr, Erlensee, EFB, 1995.

Art. Mordbrenner, in Zedler, J. H. (Ed.), Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexikon, 64 vols., (Original: Leipzig, Zedler, 1732-1750), Graz, Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt, 1961, pp. 1582-1588.