- published: 28 Mar 2012

- views: 6058

Create your page here

-

remove the playlistOrbital Period

-

remove the playlistLatest Videos

-

remove the playlistLongest Videos

- remove the playlistOrbital Period

- remove the playlistLatest Videos

- remove the playlistLongest Videos

back to playlist

Use Newton's version of Kepler's 3rd law to calculate the orbital period of the moon.

- published: 12 Feb 2010

- views: 4289

I use our knowledge of the Milky Way rotation speed and our location to work out what the period is for the sun's orbit in the galaxy.

- published: 06 Oct 2011

- views: 5847

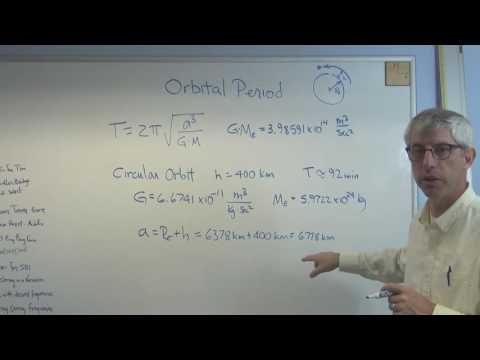

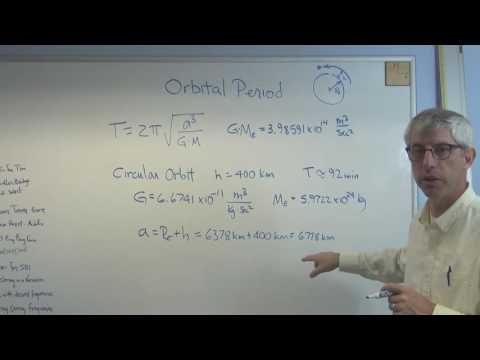

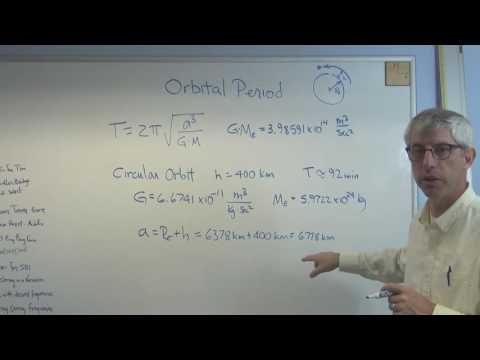

The orbital period is the time required to complete one orbit. Orbit period is easy to calculate and the expression works for both circular and elliptical orbits. I show how to calculate the period of a low Ear orbit and the period of the Earth around the Sun.

- published: 23 Jun 2016

- views: 4

Demonstrates the period (T) of a satellites orbit as a function of its earth radial distance (Re).

R1 = 1.05 Re, T1 = 90 minutes;

R2 = 3.2 Re, T2 = 12 hours;

R3 = 6.6 Re, T3 = 24 hours

Choose the correct reason for a satellite's orbit:

A) The satellite's orbit is governed by natural law (e.g. gravity, drag)

B) Symore controls the satellite's orbit with his supernatural powers

C) The satellite's orbit is just a mire illusion controlled by a simulation (e.g. movie Matrix)

- published: 17 Mar 2010

- views: 811

Orbital period

The orbital period is the time taken for a given object to make one complete orbit around another object.

When mentioned without further qualification in astronomy this refers to the sidereal period of an astronomical object, which is calculated with respect to the stars.

There are several kinds of orbital periods for objects around the Sun (or other celestial objects):

This page contains text from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia -

http://wn.com/Orbital_period

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

- Loading...

-

2:34

2:34orbital period of a satellite

orbital period of a satelliteorbital period of a satellite

-

10:53

10:53Orbital Period of the Moon

Orbital Period of the MoonOrbital Period of the Moon

Use Newton's version of Kepler's 3rd law to calculate the orbital period of the moon. -

![[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284; updated 29 May 2012; published 29 May 2012](http://web.archive.org./web/20160730151745im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/WSoOdAn44h0/0.jpg) 2:39

2:39[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284

[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284

BMS event [ノンジャンル] AUTOPLAY -

2:36

2:36bms Orbital Period - Photon Belt

bms Orbital Period - Photon Beltbms Orbital Period - Photon Belt

끵끵 -

5:10

5:10Orbital Period of Earth

Orbital Period of EarthOrbital Period of Earth

-

![[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY; updated 23 Dec 2012; published 23 Dec 2012](http://web.archive.org./web/20160730151745im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/1Z44L-BUXcI/0.jpg) 2:45

2:45[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY

[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY

-

![[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY; updated 03 Jul 2012; published 03 Jul 2012](http://web.archive.org./web/20160730151745im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/U1hXUkhh9RE/0.jpg) 2:44

2:44[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY

[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY

-

7:06

7:06Orbital Period of the Sun in the Milky Way

Orbital Period of the Sun in the Milky WayOrbital Period of the Sun in the Milky Way

I use our knowledge of the Milky Way rotation speed and our location to work out what the period is for the sun's orbit in the galaxy. -

14:18

14:18Orbital Period - Brain Waves

Orbital Period - Brain WavesOrbital Period - Brain Waves

The orbital period is the time required to complete one orbit. Orbit period is easy to calculate and the expression works for both circular and elliptical orbits. I show how to calculate the period of a low Ear orbit and the period of the Earth around the Sun. -

1:42

1:42Satellite Orbital Period vs Radial Distance

Satellite Orbital Period vs Radial DistanceSatellite Orbital Period vs Radial Distance

Demonstrates the period (T) of a satellites orbit as a function of its earth radial distance (Re). R1 = 1.05 Re, T1 = 90 minutes; R2 = 3.2 Re, T2 = 12 hours; R3 = 6.6 Re, T3 = 24 hours Choose the correct reason for a satellite's orbit: A) The satellite's orbit is governed by natural law (e.g. gravity, drag) B) Symore controls the satellite's orbit with his supernatural powers C) The satellite's orbit is just a mire illusion controlled by a simulation (e.g. movie Matrix)

-

orbital period of a satellite

-

Orbital Period of the Moon

Use Newton's version of Kepler's 3rd law to calculate the orbital period of the moon. -

[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284

BMS event [ノンジャンル] AUTOPLAY -

bms Orbital Period - Photon Belt

끵끵 -

Orbital Period of Earth

-

[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY

-

[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY

-

Orbital Period of the Sun in the Milky Way

I use our knowledge of the Milky Way rotation speed and our location to work out what the period is for the sun's orbit in the galaxy. -

Orbital Period - Brain Waves

The orbital period is the time required to complete one orbit. Orbit period is easy to calculate and the expression works for both circular and elliptical orbits. I show how to calculate the period of a low Ear orbit and the period of the Earth around the Sun. -

Satellite Orbital Period vs Radial Distance

Demonstrates the period (T) of a satellites orbit as a function of its earth radial distance (Re). R1 = 1.05 Re, T1 = 90 minutes; R2 = 3.2 Re, T2 = 12 hours; R3 = 6.6 Re, T3 = 24 hours Choose the correct reason for a satellite's orbit: A) The satellite's orbit is governed by natural law (e.g. gravity, drag) B) Symore controls the satellite's orbit with his supernatural powers C) The satellite's orbit is just a mire illusion controlled by a simulation (e.g. movie Matrix)

orbital period of a satellite

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:34

- Updated: 28 Mar 2012

- views: 6058

- published: 28 Mar 2012

- views: 6058

Orbital Period of the Moon

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:53

- Updated: 12 Feb 2010

- views: 4289

Use Newton's version of Kepler's 3rd law to calculate the orbital period of the moon.

Use Newton's version of Kepler's 3rd law to calculate the orbital period of the moon.

wn.com/Orbital Period Of The Moon

Use Newton's version of Kepler's 3rd law to calculate the orbital period of the moon.

- published: 12 Feb 2010

- views: 4289

[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:39

- Updated: 29 May 2012

- views: 498

BMS event [ノンジャンル] AUTOPLAY

BMS event [ノンジャンル] AUTOPLAY

wn.com/Bms Orbital Period 8284

bms Orbital Period - Photon Belt

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:36

- Updated: 21 Jul 2013

- views: 458

끵끵

끵끵

wn.com/Bms Orbital Period Photon Belt

끵끵

- published: 21 Jul 2013

- views: 458

Orbital Period of Earth

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:10

- Updated: 08 Mar 2016

- views: 34

- published: 08 Mar 2016

- views: 34

[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:45

- Updated: 23 Dec 2012

- views: 1847

- published: 23 Dec 2012

- views: 1847

[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:44

- Updated: 03 Jul 2012

- views: 350

- published: 03 Jul 2012

- views: 350

Orbital Period of the Sun in the Milky Way

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:06

- Updated: 06 Oct 2011

- views: 5847

I use our knowledge of the Milky Way rotation speed and our location to work out what the period is for the sun's orbit in the galaxy.

I use our knowledge of the Milky Way rotation speed and our location to work out what the period is for the sun's orbit in the galaxy.

wn.com/Orbital Period Of The Sun In The Milky Way

I use our knowledge of the Milky Way rotation speed and our location to work out what the period is for the sun's orbit in the galaxy.

- published: 06 Oct 2011

- views: 5847

Orbital Period - Brain Waves

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 14:18

- Updated: 23 Jun 2016

- views: 4

The orbital period is the time required to complete one orbit. Orbit period is easy to calculate and the expression works for both circular and elliptical orbi...

The orbital period is the time required to complete one orbit. Orbit period is easy to calculate and the expression works for both circular and elliptical orbits. I show how to calculate the period of a low Ear orbit and the period of the Earth around the Sun.

wn.com/Orbital Period Brain Waves

The orbital period is the time required to complete one orbit. Orbit period is easy to calculate and the expression works for both circular and elliptical orbits. I show how to calculate the period of a low Ear orbit and the period of the Earth around the Sun.

- published: 23 Jun 2016

- views: 4

Satellite Orbital Period vs Radial Distance

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:42

- Updated: 17 Mar 2010

- views: 811

Demonstrates the period (T) of a satellites orbit as a function of its earth radial distance (Re).

R1 = 1.05 Re, T1 = 90 minutes;

R2 = 3.2 Re, T2 = 12 hours;...

Demonstrates the period (T) of a satellites orbit as a function of its earth radial distance (Re).

R1 = 1.05 Re, T1 = 90 minutes;

R2 = 3.2 Re, T2 = 12 hours;

R3 = 6.6 Re, T3 = 24 hours

Choose the correct reason for a satellite's orbit:

A) The satellite's orbit is governed by natural law (e.g. gravity, drag)

B) Symore controls the satellite's orbit with his supernatural powers

C) The satellite's orbit is just a mire illusion controlled by a simulation (e.g. movie Matrix)

wn.com/Satellite Orbital Period Vs Radial Distance

Demonstrates the period (T) of a satellites orbit as a function of its earth radial distance (Re).

R1 = 1.05 Re, T1 = 90 minutes;

R2 = 3.2 Re, T2 = 12 hours;

R3 = 6.6 Re, T3 = 24 hours

Choose the correct reason for a satellite's orbit:

A) The satellite's orbit is governed by natural law (e.g. gravity, drag)

B) Symore controls the satellite's orbit with his supernatural powers

C) The satellite's orbit is just a mire illusion controlled by a simulation (e.g. movie Matrix)

- published: 17 Mar 2010

- views: 811

-

Orbital Period & Rotation Period

How long does the Earth and the other planets finish orbiting around the Sun? MERCURY - 88 Days VENUS - 224 Days EARTH - 365 Days MARS - 687 Days JUPITER - 11 Years SATURN - 29 Years URANUS - 84 Years NEPTUNE - 165 Years The time that the planets finish orbiting around the Sun is called a year. -------------------------------------------------------- How long does the Earth and the other planets finish rotating? MERCURY - 59 Days VENUS - 245 Days EARTH - 24 Hours MARS - 24 Hours JUPITER - 9 Hours SATURN - 10 Hours URANUS - 17 Hours NEPTUNE - 16 Hours The time that the planets finish rotating is called a day. -

A year is the orbital period of the Earth moving in its orbit around the Sun.

Use this material to improve your skills of listening, reading and speaking. Practice every day until you master it. Subscribe and share so that more people can use it. Castle TV. -

[Artcore]8284 - Orbital Period

-

Orbital evolution in Kepler-223

These animations show approximately 200,000 years of orbital evolution in the Kepler-223 planetary system. The planets’ interactions with the disk of gas and dust in which they formed caused their orbits to shrink toward their star over time at differing rates. Once two planets reach a resonant state (for example, one planet orbits its star three times every time the next planet orbits two times), the planets strongly interact with each other. The interactions become apparent in the animations as the orbits shrink (left and top right) when the orbital period ratios of neighboring planets (bottom right) get stuck at constant values. Even as the planets continue moving inwards (upper right) they do so in concert, migrating together locked in this configuration. They also cause each other’s o... -

-

Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

Pollux Beta - Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix) - Pollux Records This lo-fi version of this song / video is currently displayed via the Symphonic Distribution YouTube with full permission from the record label distributing the release. The label and its artist retain all ownership and hereby agree to all of the terms & conditions placed by Symphonic Distribution, the hosting party of this video, and all other terms as listed on their agreement. Please support the label and its artist(s) by purchasing this release via iTunes, eMusic, Rhapsody, and many more of the retailers located worldwide. If you are a label or artist and you are interested in getting your music out there, visit www.symphonicdistribution.com. -

-

Mass of Sagittarius A* from SO-2 (S2) Star's Orbital Parameters

Sagittarius A* is a suspected supermassive black hole located at the center of our Milky Way Galaxy. It is located approximately 26,000 light-years from Earth. There are a number of stars orbiting Sagittarius A* and a few have a remarkably short orbital periods. One of the stars has a period of 15.6 years and it is known as SO-2 (also S-2). The semi-major axis and period of SO-2 about Sagittarius A*are the orbital parameters used to calculate the mass of Sagittarius A* (also known as Sgr A*). The mass of Sgr A* is found to be the equivalent of about 4 million Suns. Andrew R. Ochadlick Jr. received a Ph.D. in Physics from the State University of New York at Albany (SUNYA) and is a career physicist with university, government and industry R&D; experience and teaching experience at the u...

Orbital Period & Rotation Period

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:32

- Updated: 26 Jun 2016

- views: 21

How long does the Earth and the other planets finish orbiting around the Sun?

MERCURY - 88 Days

VENUS - 224 Days

EARTH - 365 Days

MARS - 687 Days

JUPITER - 11 Y...

How long does the Earth and the other planets finish orbiting around the Sun?

MERCURY - 88 Days

VENUS - 224 Days

EARTH - 365 Days

MARS - 687 Days

JUPITER - 11 Years

SATURN - 29 Years

URANUS - 84 Years

NEPTUNE - 165 Years

The time that the planets finish orbiting around the Sun is called a year.

--------------------------------------------------------

How long does the Earth and the other planets finish rotating?

MERCURY - 59 Days

VENUS - 245 Days

EARTH - 24 Hours

MARS - 24 Hours

JUPITER - 9 Hours

SATURN - 10 Hours

URANUS - 17 Hours

NEPTUNE - 16 Hours

The time that the planets finish rotating is called a day.

wn.com/Orbital Period Rotation Period

How long does the Earth and the other planets finish orbiting around the Sun?

MERCURY - 88 Days

VENUS - 224 Days

EARTH - 365 Days

MARS - 687 Days

JUPITER - 11 Years

SATURN - 29 Years

URANUS - 84 Years

NEPTUNE - 165 Years

The time that the planets finish orbiting around the Sun is called a year.

--------------------------------------------------------

How long does the Earth and the other planets finish rotating?

MERCURY - 59 Days

VENUS - 245 Days

EARTH - 24 Hours

MARS - 24 Hours

JUPITER - 9 Hours

SATURN - 10 Hours

URANUS - 17 Hours

NEPTUNE - 16 Hours

The time that the planets finish rotating is called a day.

- published: 26 Jun 2016

- views: 21

A year is the orbital period of the Earth moving in its orbit around the Sun.

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:28

- Updated: 17 Jun 2016

- views: 32

Use this material to improve your skills of listening, reading and speaking. Practice every day until you master it. Subscribe and share so that more people can...

Use this material to improve your skills of listening, reading and speaking. Practice every day until you master it. Subscribe and share so that more people can use it. Castle TV.

wn.com/A Year Is The Orbital Period Of The Earth Moving In Its Orbit Around The Sun.

Use this material to improve your skills of listening, reading and speaking. Practice every day until you master it. Subscribe and share so that more people can use it. Castle TV.

- published: 17 Jun 2016

- views: 32

[Artcore]8284 - Orbital Period

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:36

- Updated: 06 Jun 2016

- views: 89

- published: 06 Jun 2016

- views: 89

Orbital evolution in Kepler-223

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:18

- Updated: 11 May 2016

- views: 9511

These animations show approximately 200,000 years of orbital evolution in the Kepler-223 planetary system. The planets’ interactions with the disk of gas and du...

These animations show approximately 200,000 years of orbital evolution in the Kepler-223 planetary system. The planets’ interactions with the disk of gas and dust in which they formed caused their orbits to shrink toward their star over time at differing rates. Once two planets reach a resonant state (for example, one planet orbits its star three times every time the next planet orbits two times), the planets strongly interact with each other. The interactions become apparent in the animations as the orbits shrink (left and top right) when the orbital period ratios of neighboring planets (bottom right) get stuck at constant values. Even as the planets continue moving inwards (upper right) they do so in concert, migrating together locked in this configuration. They also cause each other’s orbits to change from nearly circular to elliptical. This is represented by the varying orbits on the left panel and the spread of the orbital distances for each individual planet in the upper right. (Credit: Daniel Fabrycky and Cezary Migazewski)

wn.com/Orbital Evolution In Kepler 223

These animations show approximately 200,000 years of orbital evolution in the Kepler-223 planetary system. The planets’ interactions with the disk of gas and dust in which they formed caused their orbits to shrink toward their star over time at differing rates. Once two planets reach a resonant state (for example, one planet orbits its star three times every time the next planet orbits two times), the planets strongly interact with each other. The interactions become apparent in the animations as the orbits shrink (left and top right) when the orbital period ratios of neighboring planets (bottom right) get stuck at constant values. Even as the planets continue moving inwards (upper right) they do so in concert, migrating together locked in this configuration. They also cause each other’s orbits to change from nearly circular to elliptical. This is represented by the varying orbits on the left panel and the spread of the orbital distances for each individual planet in the upper right. (Credit: Daniel Fabrycky and Cezary Migazewski)

- published: 11 May 2016

- views: 9511

PXR047 / Pollux Beta - Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:05

- Updated: 11 Apr 2016

- views: 27

Buy from Beatport: https://pro.beatport.com/label/pollux-records/14760

Contact : polluxrecords@gmail.com

Web-Site : http://www.polluxrecords.com

Subscribe : ht...

Buy from Beatport: https://pro.beatport.com/label/pollux-records/14760

Contact : polluxrecords@gmail.com

Web-Site : http://www.polluxrecords.com

Subscribe : http://www.youtube.com/polluxrecords

Like : https://www.facebook.com/polluxrec

wn.com/Pxr047 Pollux Beta Orbital Period 589 Days (Original Mix)

Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:06

- Updated: 04 Mar 2016

- views: 5

Pollux Beta - Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix) - Pollux Records

This lo-fi version of this song / video is currently displayed via the S...

Pollux Beta - Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix) - Pollux Records

This lo-fi version of this song / video is currently displayed via the Symphonic Distribution YouTube with full permission from the record label distributing the release. The label and its artist retain all ownership and hereby agree to all of the terms & conditions placed by Symphonic Distribution, the hosting party of this video, and all other terms as listed on their agreement. Please support the label and its artist(s) by purchasing this release via iTunes, eMusic, Rhapsody, and many more of the retailers located worldwide. If you are a label or artist and you are interested in getting your music out there, visit www.symphonicdistribution.com.

wn.com/Pollux Beta Orbital Period 589 Days (Original Mix)

Pollux Beta - Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix) - Pollux Records

This lo-fi version of this song / video is currently displayed via the Symphonic Distribution YouTube with full permission from the record label distributing the release. The label and its artist retain all ownership and hereby agree to all of the terms & conditions placed by Symphonic Distribution, the hosting party of this video, and all other terms as listed on their agreement. Please support the label and its artist(s) by purchasing this release via iTunes, eMusic, Rhapsody, and many more of the retailers located worldwide. If you are a label or artist and you are interested in getting your music out there, visit www.symphonicdistribution.com.

- published: 04 Mar 2016

- views: 5

Elite Dangerous planet's orbital moving simulation in different flying modes

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:50

- Updated: 10 Feb 2016

- views: 230

Planets are moving smoothly in supercruise mode and in shorts dashes in normal flying mode.

Tested on Merope 5 A, 1.1 D orbital period

Planets are moving smoothly in supercruise mode and in shorts dashes in normal flying mode.

Tested on Merope 5 A, 1.1 D orbital period

wn.com/Elite Dangerous Planet's Orbital Moving Simulation In Different Flying Modes

Mass of Sagittarius A* from SO-2 (S2) Star's Orbital Parameters

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:09

- Updated: 05 Feb 2016

- views: 79

Sagittarius A* is a suspected supermassive black hole located at the center of our Milky Way Galaxy. It is located approximately 26,000 light-years from Earth....

Sagittarius A* is a suspected supermassive black hole located at the center of our Milky Way Galaxy. It is located approximately 26,000 light-years from Earth. There are a number of stars orbiting Sagittarius A* and a few have a remarkably short orbital periods. One of the stars has a period of 15.6 years and it is known as SO-2 (also S-2). The semi-major axis and period of SO-2 about Sagittarius A*are the orbital parameters used to calculate the mass of Sagittarius A* (also known as Sgr A*). The mass of Sgr A* is found to be the equivalent of about 4 million Suns. Andrew R. Ochadlick Jr. received a Ph.D. in Physics from the State University of New York at Albany (SUNYA) and is a career physicist with university, government and industry R&D; experience and teaching experience at the undergraduate and graduate level. He may be reached at andrewochadlickphysics@alumni.albany.edu .

wn.com/Mass Of Sagittarius A From So 2 (S2) Star's Orbital Parameters

Sagittarius A* is a suspected supermassive black hole located at the center of our Milky Way Galaxy. It is located approximately 26,000 light-years from Earth. There are a number of stars orbiting Sagittarius A* and a few have a remarkably short orbital periods. One of the stars has a period of 15.6 years and it is known as SO-2 (also S-2). The semi-major axis and period of SO-2 about Sagittarius A*are the orbital parameters used to calculate the mass of Sagittarius A* (also known as Sgr A*). The mass of Sgr A* is found to be the equivalent of about 4 million Suns. Andrew R. Ochadlick Jr. received a Ph.D. in Physics from the State University of New York at Albany (SUNYA) and is a career physicist with university, government and industry R&D; experience and teaching experience at the undergraduate and graduate level. He may be reached at andrewochadlickphysics@alumni.albany.edu .

- published: 05 Feb 2016

- views: 79

-

Molecular Orbital Theory IV: Period 2 Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules

Molecular orbital diagrams of Li2, Be2, B2, C2, N2, O2, F2, and Ne2. Long winded video, but it explains how the p orbitals form sigma and pi MO's. -

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens - Konstantin Batygin - SETI Talks The statistics of extrasolar planetary systems indicate that the default mode of planetary formation generates planets with orbital periods shorter than 100 days, and masses substantially exceeding that of the Earth. When viewed in this context, the Solar System, which contains no planets interior to Mercury’s 88-day orbit, is unusual. Extra-solar planetary detection surveys also suggest that planets with masses and periods broadly similar to Jupiter’s are somewhat uncommon, with occurrence fraction of less than approximately 10%. In this talk, Dr. Batygin will present calculations which show that a popular formation scenario for Jupiter and Saturn, in which Jupiter migrates inward fr... -

Lec 22: Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, and Maneuvers | 8.01 Classical Mechanics (Walter Lewin)

Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, Change of Orbits, and the famous passing of a Ham Sandwich. Kepler's three Laws summarize the motion of the planets in our solar system. Following Newton's law of universal gravitation, the conservation of angular momentum and mechanical energy allow us to calculate the semimajor axis of the elliptical orbits, the orbital period and other orbital parameters. All we have to know is one position and the associated velocity of a planet and the entire orbit follows. This lecture is part of 8.01 Physics I: Classical Mechanics, as taught in Fall 1999 by Dr. Walter Lewin at MIT. This video was formerly hosted on the YouTube channel MIT OpenCourseWare. This version was downloaded from the Internet Archive, at https://archive.org/details/MIT8.01F99/. Attribution... -

Kerbal Space Program - Part 2 - Orbital Docking, Transfers and Trigonometry (Docking 101)

Join me on Twitter: http://twitter.com/WhatDaMath Hello and welcome to What Da Math. In this video I will be using Kerbal Space Program and trigonometry, specifically cosine waves as well as the orbital period formulas to calculate a perfect time for an orbital transfer while orbiting Kerbin. Thank you and please subscribe! -

KEPLER 186F Discovered And Life After Earth - 2016 Documentary - 2 Hours

Kepler-186f is an exoplanet orbiting the red dwarf Kepler-186,[4][5][6] about 490 light-years (151 pc) from the Earth.[1] It is the first planet with a radius similar to Earth's to be discovered in the habitable zone of another star. NASA's Kepler spacecraft detected it using the transit method, along with four additional planets orbiting much closer to the star (all modestly larger than Earth).[5] Analysis of three years of data was required to find its signal.[7] The results were presented initially at a conference on 19 March 2014[8] and some details were reported in the media at the time.[9][10] The public announcement was on 17 April 2014,[2] followed by publication in Science.[1] Orbital parameters relative to habitable zone[edit] Kepler-186f orbits an M-dwarf star with about 4% of t... -

【東方】 交響曲「幻想郷世界」

ニコニコ動画から転載 http://www.nicovideo.jp/watch/sm16495241 東方アレンジメドレー100曲です -

BUMP OF CHICKEN PONTSUKA!! 2007年4月8日

BUMP OF CHICKEN バンプオブチキン ポンツカ 藤原基央さん28歳誕生日回 記念すべきorbital periodですね -

Class 10+1, Chapter 6, Question 14, Orbital speed, Time period, Energy of satelite

Class 10+1, Chapter 6, Question 14, Orbital speed, Time period, Energy of satelite -

The Black Knight Satellite 2014 new information

Black Knight also known as the Black Knight satellite is an alleged object orbiting Earth in near-polar orbit that ufologists and fringe authors believe is approximately 13,000 years old and of extraterrestrial origin. However it is most probable that Black Knight is the result of a conflation of a number of unrelated stories.[1] Stories[edit] Fringe authors claim that there is a connection between long delayed echos and reports that Nikola Tesla picked up a repeating radio signal in 1899 which he believed was coming from space. The satellite explanation originated in 1954 when newspapers including the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the San Francisco Examiner ran stories attributed to retired naval aviation major and UFO researcher Donald Keyhoe saying that the US Air Force had reported that... -

Bruce Leybourne - Validation of Earth Endogenous Theory

Climate oscillations with periods ~20 and ~60-years, appear synchronized to Jupiter (12-years) and Saturn (29-years) orbital periods, while Moon’s orbital cycle appears synchronized to an Earthy 9.1 -year temperature cycle (Scafetta, 2010). The Earth’s magnetic moment % decay over the past century reflects 30 -year weakening-trends and 30-year strengthening-trends of solar magnetic field, exhibiting the same periods (60-years) well correlated to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). In addition, magnetic trends exhibit 3 smaller inflection changes during the 30-year trends which appears correlated: (i) with the 9.1-year Moon orbital cycle and (ii) with El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) patterns overprinted with the 22-year Hale Cycle, more closely associated with a Jupit...

Molecular Orbital Theory IV: Period 2 Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 24:21

- Updated: 07 Aug 2011

- views: 157230

Molecular orbital diagrams of Li2, Be2, B2, C2, N2, O2, F2, and Ne2. Long winded video, but it explains how the p orbitals form sigma and pi MO's.

Molecular orbital diagrams of Li2, Be2, B2, C2, N2, O2, F2, and Ne2. Long winded video, but it explains how the p orbitals form sigma and pi MO's.

wn.com/Molecular Orbital Theory Iv Period 2 Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules

Molecular orbital diagrams of Li2, Be2, B2, C2, N2, O2, F2, and Ne2. Long winded video, but it explains how the p orbitals form sigma and pi MO's.

- published: 07 Aug 2011

- views: 157230

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 66:01

- Updated: 16 Apr 2015

- views: 5570

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens - Konstantin Batygin - SETI Talks

The statistics of extrasolar planetary systems indicate ...

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens - Konstantin Batygin - SETI Talks

The statistics of extrasolar planetary systems indicate that the default mode of planetary formation generates planets with orbital periods shorter than 100 days, and masses substantially exceeding that of the Earth. When viewed in this context, the Solar System, which contains no planets interior to Mercury’s 88-day orbit, is unusual.

Extra-solar planetary detection surveys also suggest that planets with masses and periods broadly similar to Jupiter’s are somewhat uncommon, with occurrence fraction of less than approximately 10%.

In this talk, Dr. Batygin will present calculations which show that a popular formation scenario for Jupiter and Saturn, in which Jupiter migrates inward from a greater than 5AU to approximately 1.5 AU and then reverses direction, can explain the low overall mass of the Solar System’s terrestrial planets, as well as the absence of planets with a less than 0.4 AU. Jupiter’s inward migration entrained s greater than 10 − 100 km planetesimals into low - order mean-motion resonances, shepherding of order 10 Earth masses of this material into the a ∼ 1 AU region while exciting substantial orbital eccentricity (e ∼ 0.2 − 0.4).

He will argue that under these conditions, a collisional cascade will ensue, generating a planetesimal disk that would have flushed any preexisting short-period super-Earth-like planets into the Sun. In this scenario, the Solar System’s terrestrial planets formed from gas-starved mass-depleted debris that remained after the primary period of dynamical evolution.

wn.com/Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture Through An Extrasolar Lens

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens - Konstantin Batygin - SETI Talks

The statistics of extrasolar planetary systems indicate that the default mode of planetary formation generates planets with orbital periods shorter than 100 days, and masses substantially exceeding that of the Earth. When viewed in this context, the Solar System, which contains no planets interior to Mercury’s 88-day orbit, is unusual.

Extra-solar planetary detection surveys also suggest that planets with masses and periods broadly similar to Jupiter’s are somewhat uncommon, with occurrence fraction of less than approximately 10%.

In this talk, Dr. Batygin will present calculations which show that a popular formation scenario for Jupiter and Saturn, in which Jupiter migrates inward from a greater than 5AU to approximately 1.5 AU and then reverses direction, can explain the low overall mass of the Solar System’s terrestrial planets, as well as the absence of planets with a less than 0.4 AU. Jupiter’s inward migration entrained s greater than 10 − 100 km planetesimals into low - order mean-motion resonances, shepherding of order 10 Earth masses of this material into the a ∼ 1 AU region while exciting substantial orbital eccentricity (e ∼ 0.2 − 0.4).

He will argue that under these conditions, a collisional cascade will ensue, generating a planetesimal disk that would have flushed any preexisting short-period super-Earth-like planets into the Sun. In this scenario, the Solar System’s terrestrial planets formed from gas-starved mass-depleted debris that remained after the primary period of dynamical evolution.

- published: 16 Apr 2015

- views: 5570

Lec 22: Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, and Maneuvers | 8.01 Classical Mechanics (Walter Lewin)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 49:09

- Updated: 11 Dec 2014

- views: 17839

Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, Change of Orbits, and the famous passing of a Ham Sandwich. Kepler's three Laws summarize the motion of the planets in our sol...

Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, Change of Orbits, and the famous passing of a Ham Sandwich. Kepler's three Laws summarize the motion of the planets in our solar system. Following Newton's law of universal gravitation, the conservation of angular momentum and mechanical energy allow us to calculate the semimajor axis of the elliptical orbits, the orbital period and other orbital parameters. All we have to know is one position and the associated velocity of a planet and the entire orbit follows.

This lecture is part of 8.01 Physics I: Classical Mechanics, as taught in Fall 1999 by Dr. Walter Lewin at MIT.

This video was formerly hosted on the YouTube channel MIT OpenCourseWare.

This version was downloaded from the Internet Archive, at https://archive.org/details/MIT8.01F99/.

Attribution: MIT OpenCourseWare

License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/.

More information at http://ocw.mit.edu/terms/.

This YouTube channel is independently operated. It is neither affiliated with nor endorsed by MIT, MIT OpenCourseWare, the Internet Archive, or Dr. Lewin.

wn.com/Lec 22 Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, And Maneuvers | 8.01 Classical Mechanics (Walter Lewin)

Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, Change of Orbits, and the famous passing of a Ham Sandwich. Kepler's three Laws summarize the motion of the planets in our solar system. Following Newton's law of universal gravitation, the conservation of angular momentum and mechanical energy allow us to calculate the semimajor axis of the elliptical orbits, the orbital period and other orbital parameters. All we have to know is one position and the associated velocity of a planet and the entire orbit follows.

This lecture is part of 8.01 Physics I: Classical Mechanics, as taught in Fall 1999 by Dr. Walter Lewin at MIT.

This video was formerly hosted on the YouTube channel MIT OpenCourseWare.

This version was downloaded from the Internet Archive, at https://archive.org/details/MIT8.01F99/.

Attribution: MIT OpenCourseWare

License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/.

More information at http://ocw.mit.edu/terms/.

This YouTube channel is independently operated. It is neither affiliated with nor endorsed by MIT, MIT OpenCourseWare, the Internet Archive, or Dr. Lewin.

- published: 11 Dec 2014

- views: 17839

Kerbal Space Program - Part 2 - Orbital Docking, Transfers and Trigonometry (Docking 101)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 20:58

- Updated: 06 Dec 2014

- views: 431

Join me on Twitter: http://twitter.com/WhatDaMath

Hello and welcome to What Da Math.

In this video I will be using Kerbal Space Program and trigonometry, spec...

Join me on Twitter: http://twitter.com/WhatDaMath

Hello and welcome to What Da Math.

In this video I will be using Kerbal Space Program and trigonometry, specifically cosine waves as well as the orbital period formulas to calculate a perfect time for an orbital transfer while orbiting Kerbin.

Thank you and please subscribe!

wn.com/Kerbal Space Program Part 2 Orbital Docking, Transfers And Trigonometry (Docking 101)

Join me on Twitter: http://twitter.com/WhatDaMath

Hello and welcome to What Da Math.

In this video I will be using Kerbal Space Program and trigonometry, specifically cosine waves as well as the orbital period formulas to calculate a perfect time for an orbital transfer while orbiting Kerbin.

Thank you and please subscribe!

- published: 06 Dec 2014

- views: 431

KEPLER 186F Discovered And Life After Earth - 2016 Documentary - 2 Hours

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 114:47

- Updated: 10 Jun 2016

- views: 201

Kepler-186f is an exoplanet orbiting the red dwarf Kepler-186,[4][5][6] about 490 light-years (151 pc) from the Earth.[1] It is the first planet with a radius s...

Kepler-186f is an exoplanet orbiting the red dwarf Kepler-186,[4][5][6] about 490 light-years (151 pc) from the Earth.[1] It is the first planet with a radius similar to Earth's to be discovered in the habitable zone of another star. NASA's Kepler spacecraft detected it using the transit method, along with four additional planets orbiting much closer to the star (all modestly larger than Earth).[5] Analysis of three years of data was required to find its signal.[7] The results were presented initially at a conference on 19 March 2014[8] and some details were reported in the media at the time.[9][10] The public announcement was on 17 April 2014,[2] followed by publication in Science.[1]

Orbital parameters relative to habitable zone[edit]

Kepler-186f orbits an M-dwarf star with about 4% of the Sun's luminosity with an orbital period of 129.9 days and an orbital radius of about 0.36[1] or 0.40[3] times that of Earth's (compared to 0.39 AU for Mercury). The habitable zone for this system is estimated conservatively to extend over distances receiving from 88% to 25% of Earth's illumination (from 0.22 to 0.40 AU).[1] Kepler-186f receives about 32%, placing it within the conservative zone but near the outer edge, similar to the position of Mars in our Solar System.[1]

Mass, density and composition[edit]

The only physical property directly derivable from the observations (besides the orbital period) is the ratio of the radius of the planet to that of the central star, which follows from the amount of occultation of stellar light during a transit. This ratio was measured to be 0.021.[1] This yields a planetary radius of 1.11±0.14 times that of Earth,[2][5] taking into account uncertainty in the star's diameter and the degree of occultation. Thus, the planet is about 11% larger in radius than Earth (between 4.5% smaller and 26.5% larger), giving a volume about 1.37 times that of Earth (between 0.87 and 2.03 times as large).

There is a very wide range of possible masses that can be calculated by combining the radius with densities derived from the possible types of matter that planets can be made from; it could be a rocky terrestrial planet or a lower density ocean planet with a thick atmosphere. However, a massive hydrogen/helium (H/He) atmosphere is thought to be unlikely in a planet with a radius below 1.5 R⊕. Planets with radii of more than 1.5 times that of Earth tend to accumulate the thick atmospheres that would make them less likely to be habitable.[11] Red dwarfs emit a much stronger extreme ultraviolet (XUV) flux when young than later in life; the planet's primordial atmosphere would have been subjected to elevated photoevaporation during that period, which would probably have largely removed any H/He-rich envelope through hydrodynamic mass loss.[1] Mass estimates range from 0.32 M⊕ for a pure water/ice composition to 3.77 M⊕ if made up entirely of iron (both implausible extremes). For a body with radius 1.11 R⊕, a composition similar to Earth’s (1/3 iron, 2/3 silicate rock) yields a mass of 1.44 M⊕,[1] taking into account the higher density due to the higher average pressure compared to Earth.

Formation, tidal evolution and habitability[edit]

The star hosts four other planets discovered so far, though Kepler-186 b, c, d, and e (in order of increasing orbital radius) are too close to the star, and are therefore too hot to have liquid water. The four innermost planets are probably tidally locked but Kepler-186f is in a higher orbit, where the star's tidal effects are much weaker, so there may not have been enough time for its spin to slow down that much. Because of the very slow evolution of red dwarfs, the age of the Kepler-186 system is poorly constrained, although it is likely to be greater than a few billion years.[3] There is an approximately 50% chance it is tidally locked. Since it is closer to its star than Earth is to the Sun, it will probably rotate much more slowly than Earth; its day could be weeks or months long (see Tidal effects on rotation rate, axial tilt and orbit).[12]

Artist's concept of a rocky Earth-sized exoplanet in the habitable zone of its host star, possibly compatible with Kepler-186f’s known data (NASA/SETI/JPL)

Kepler-186f's axial tilt (obliquity) is likely very small, in which case it wouldn't have tilt-induced seasons as Earth and Mars do. Its orbit is probably close to circular,[12] so it will also lack eccentricity-induced seasonal changes like those of Mars. However, the axial tilt could be larger (about 23 degrees) if another undetected nontransiting planet orbits between it and Kepler-186e; planetary formation simulations have shown that the presence of at least one additional planet in this region is likely. If such a planet exists, it cannot be much more massive than Earth as it would then cause orbital instabilities.[3]

wn.com/Kepler 186F Discovered And Life After Earth 2016 Documentary 2 Hours

Kepler-186f is an exoplanet orbiting the red dwarf Kepler-186,[4][5][6] about 490 light-years (151 pc) from the Earth.[1] It is the first planet with a radius similar to Earth's to be discovered in the habitable zone of another star. NASA's Kepler spacecraft detected it using the transit method, along with four additional planets orbiting much closer to the star (all modestly larger than Earth).[5] Analysis of three years of data was required to find its signal.[7] The results were presented initially at a conference on 19 March 2014[8] and some details were reported in the media at the time.[9][10] The public announcement was on 17 April 2014,[2] followed by publication in Science.[1]

Orbital parameters relative to habitable zone[edit]

Kepler-186f orbits an M-dwarf star with about 4% of the Sun's luminosity with an orbital period of 129.9 days and an orbital radius of about 0.36[1] or 0.40[3] times that of Earth's (compared to 0.39 AU for Mercury). The habitable zone for this system is estimated conservatively to extend over distances receiving from 88% to 25% of Earth's illumination (from 0.22 to 0.40 AU).[1] Kepler-186f receives about 32%, placing it within the conservative zone but near the outer edge, similar to the position of Mars in our Solar System.[1]

Mass, density and composition[edit]

The only physical property directly derivable from the observations (besides the orbital period) is the ratio of the radius of the planet to that of the central star, which follows from the amount of occultation of stellar light during a transit. This ratio was measured to be 0.021.[1] This yields a planetary radius of 1.11±0.14 times that of Earth,[2][5] taking into account uncertainty in the star's diameter and the degree of occultation. Thus, the planet is about 11% larger in radius than Earth (between 4.5% smaller and 26.5% larger), giving a volume about 1.37 times that of Earth (between 0.87 and 2.03 times as large).

There is a very wide range of possible masses that can be calculated by combining the radius with densities derived from the possible types of matter that planets can be made from; it could be a rocky terrestrial planet or a lower density ocean planet with a thick atmosphere. However, a massive hydrogen/helium (H/He) atmosphere is thought to be unlikely in a planet with a radius below 1.5 R⊕. Planets with radii of more than 1.5 times that of Earth tend to accumulate the thick atmospheres that would make them less likely to be habitable.[11] Red dwarfs emit a much stronger extreme ultraviolet (XUV) flux when young than later in life; the planet's primordial atmosphere would have been subjected to elevated photoevaporation during that period, which would probably have largely removed any H/He-rich envelope through hydrodynamic mass loss.[1] Mass estimates range from 0.32 M⊕ for a pure water/ice composition to 3.77 M⊕ if made up entirely of iron (both implausible extremes). For a body with radius 1.11 R⊕, a composition similar to Earth’s (1/3 iron, 2/3 silicate rock) yields a mass of 1.44 M⊕,[1] taking into account the higher density due to the higher average pressure compared to Earth.

Formation, tidal evolution and habitability[edit]

The star hosts four other planets discovered so far, though Kepler-186 b, c, d, and e (in order of increasing orbital radius) are too close to the star, and are therefore too hot to have liquid water. The four innermost planets are probably tidally locked but Kepler-186f is in a higher orbit, where the star's tidal effects are much weaker, so there may not have been enough time for its spin to slow down that much. Because of the very slow evolution of red dwarfs, the age of the Kepler-186 system is poorly constrained, although it is likely to be greater than a few billion years.[3] There is an approximately 50% chance it is tidally locked. Since it is closer to its star than Earth is to the Sun, it will probably rotate much more slowly than Earth; its day could be weeks or months long (see Tidal effects on rotation rate, axial tilt and orbit).[12]

Artist's concept of a rocky Earth-sized exoplanet in the habitable zone of its host star, possibly compatible with Kepler-186f’s known data (NASA/SETI/JPL)

Kepler-186f's axial tilt (obliquity) is likely very small, in which case it wouldn't have tilt-induced seasons as Earth and Mars do. Its orbit is probably close to circular,[12] so it will also lack eccentricity-induced seasonal changes like those of Mars. However, the axial tilt could be larger (about 23 degrees) if another undetected nontransiting planet orbits between it and Kepler-186e; planetary formation simulations have shown that the presence of at least one additional planet in this region is likely. If such a planet exists, it cannot be much more massive than Earth as it would then cause orbital instabilities.[3]

- published: 10 Jun 2016

- views: 201

【東方】 交響曲「幻想郷世界」

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 55:11

- Updated: 19 Aug 2012

- views: 105995

ニコニコ動画から転載

http://www.nicovideo.jp/watch/sm16495241

東方アレンジメドレー100曲です

ニコニコ動画から転載

http://www.nicovideo.jp/watch/sm16495241

東方アレンジメドレー100曲です

wn.com/【東方】 交響曲「幻想郷世界」

ニコニコ動画から転載

http://www.nicovideo.jp/watch/sm16495241

東方アレンジメドレー100曲です

- published: 19 Aug 2012

- views: 105995

BUMP OF CHICKEN PONTSUKA!! 2007年4月8日

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 30:37

- Updated: 10 Sep 2015

- views: 4622

BUMP OF CHICKEN

バンプオブチキン

ポンツカ

藤原基央さん28歳誕生日回

記念すべきorbital periodですね

BUMP OF CHICKEN

バンプオブチキン

ポンツカ

藤原基央さん28歳誕生日回

記念すべきorbital periodですね

wn.com/Bump Of Chicken Pontsuka 2007年4月8日

BUMP OF CHICKEN

バンプオブチキン

ポンツカ

藤原基央さん28歳誕生日回

記念すべきorbital periodですね

- published: 10 Sep 2015

- views: 4622

Class 10+1, Chapter 6, Question 14, Orbital speed, Time period, Energy of satelite

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 24:37

- Updated: 08 Aug 2015

- views: 26

Class 10+1, Chapter 6, Question 14, Orbital speed, Time period, Energy of satelite

- published: 08 Aug 2015

- views: 26

The Black Knight Satellite 2014 new information

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 32:27

- Updated: 12 Oct 2014

- views: 1114770

Black Knight also known as the Black Knight satellite is an alleged object orbiting Earth in near-polar orbit that ufologists and fringe authors believe is appr...

Black Knight also known as the Black Knight satellite is an alleged object orbiting Earth in near-polar orbit that ufologists and fringe authors believe is approximately 13,000 years old and of extraterrestrial origin. However it is most probable that Black Knight is the result of a conflation of a number of unrelated stories.[1]

Stories[edit]

Fringe authors claim that there is a connection between long delayed echos and reports that Nikola Tesla picked up a repeating radio signal in 1899 which he believed was coming from space. The satellite explanation originated in 1954 when newspapers including the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the San Francisco Examiner ran stories attributed to retired naval aviation major and UFO researcher Donald Keyhoe saying that the US Air Force had reported that two satellites orbiting the Earth had been detected. At this time no man-made satellites had been launched.[2]

In February 1960 there was a further report that the US Navy had detected a dark, tumbling object in an orbit inclined at 79° from the equator with an orbital period of 104.5 minutes. Its orbit was also highly eccentric with an apogee of 1,728 km (1,074 mi) and a perigee of only 216 km (134 mi). At the time the Navy was tracking a fragment of casing from the Discoverer VIII satellite launch which had a very similar orbit. The dark object was later confirmed to be another part of this casing that had been presumed lost.[2][3]

In 1973 the Scottish writer Duncan Lunan analyzed the data from the Norwegian radio researchers, coming to the conclusion that they produced a star chart pointing the way to Epsilon Boötis, a double star in the constellation of Boötes. Lunan's hypothesis was that these signals were being transmitted from a 12,600 year old object located at one of Earth's Lagrangian points. Lunan later found that his analysis had been based on flawed data and withdrew it, and at no time did he associate it with the unidentified orbiting object.[4]

An object photographed in 1998 during the STS-88 mission has been widely claimed to be this "alien artifact". However, it is more probable that the photographs are of a thermal blanket that had been lost during an EVA.[1] Alternatively, people analyzing these pictures have suggested that it could be the Pakal Spacecraft, a supposed Mayan spacecraft written about by controversial pseudoarchiological author Erich von Däniken.[5]

wn.com/The Black Knight Satellite 2014 New Information

Black Knight also known as the Black Knight satellite is an alleged object orbiting Earth in near-polar orbit that ufologists and fringe authors believe is approximately 13,000 years old and of extraterrestrial origin. However it is most probable that Black Knight is the result of a conflation of a number of unrelated stories.[1]

Stories[edit]

Fringe authors claim that there is a connection between long delayed echos and reports that Nikola Tesla picked up a repeating radio signal in 1899 which he believed was coming from space. The satellite explanation originated in 1954 when newspapers including the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the San Francisco Examiner ran stories attributed to retired naval aviation major and UFO researcher Donald Keyhoe saying that the US Air Force had reported that two satellites orbiting the Earth had been detected. At this time no man-made satellites had been launched.[2]

In February 1960 there was a further report that the US Navy had detected a dark, tumbling object in an orbit inclined at 79° from the equator with an orbital period of 104.5 minutes. Its orbit was also highly eccentric with an apogee of 1,728 km (1,074 mi) and a perigee of only 216 km (134 mi). At the time the Navy was tracking a fragment of casing from the Discoverer VIII satellite launch which had a very similar orbit. The dark object was later confirmed to be another part of this casing that had been presumed lost.[2][3]

In 1973 the Scottish writer Duncan Lunan analyzed the data from the Norwegian radio researchers, coming to the conclusion that they produced a star chart pointing the way to Epsilon Boötis, a double star in the constellation of Boötes. Lunan's hypothesis was that these signals were being transmitted from a 12,600 year old object located at one of Earth's Lagrangian points. Lunan later found that his analysis had been based on flawed data and withdrew it, and at no time did he associate it with the unidentified orbiting object.[4]

An object photographed in 1998 during the STS-88 mission has been widely claimed to be this "alien artifact". However, it is more probable that the photographs are of a thermal blanket that had been lost during an EVA.[1] Alternatively, people analyzing these pictures have suggested that it could be the Pakal Spacecraft, a supposed Mayan spacecraft written about by controversial pseudoarchiological author Erich von Däniken.[5]

- published: 12 Oct 2014

- views: 1114770

Bruce Leybourne - Validation of Earth Endogenous Theory

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 38:51

- Updated: 29 Jun 2015

- views: 437

Climate oscillations with periods ~20 and ~60-years, appear synchronized to Jupiter (12-years) and Saturn (29-years) orbital periods, while Moon’s orbital ...

Climate oscillations with periods ~20 and ~60-years, appear synchronized to Jupiter (12-years) and Saturn (29-years) orbital periods, while Moon’s orbital cycle appears synchronized to an Earthy 9.1 -year temperature cycle (Scafetta, 2010). The Earth’s magnetic moment % decay over the past century reflects 30 -year weakening-trends and 30-year strengthening-trends of solar magnetic field, exhibiting the same periods (60-years) well correlated to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). In addition, magnetic trends exhibit 3 smaller inflection changes during the 30-year trends which appears correlated: (i) with the 9.1-year Moon orbital cycle and (ii) with El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) patterns overprinted with the 22-year Hale Cycle, more closely associated with a Jupiter affect. Finally the MaddenJulian Oscillation (MJO) 40-day power-spectrum correlates with the period in which Earth experiences a complete solar rotation and interestingly also a north-south oscillation of earthquakes along the Western Pacific rim (Krishnamurti, 2009). A review of the literature indicates that El Niño’s have 6-month earthquake precursors (Walker, 1995). In addition the Nation Earthquake information Center database reveals that large 9.0+ earthquakes only occur along the 30-year cooling trend during solar magnetic field strengthening. During this same period Earth also experiences electromagnetic (e.m.) induction charging, mostly from southern plasma ring-currents coupled to telluric currents in the ridge encircling Antarctica. This transformer effect from the south-pole exerts climate control over the planet via aligned tectonic vortex structures along the Western Pacific rim, electrically connected to the core. This is consistent with the “Earth Endogenous Energy” theory (Gregori, 2002 – Earth as a rechargeable battery/capacitor).

Link to full paper:http://worldnpa.org/climate-oscillations-mjo-enso-pdo-considered-with-validation-of-earth-endogenous-energy-theory/

wn.com/Bruce Leybourne Validation Of Earth Endogenous Theory

Climate oscillations with periods ~20 and ~60-years, appear synchronized to Jupiter (12-years) and Saturn (29-years) orbital periods, while Moon’s orbital cycle appears synchronized to an Earthy 9.1 -year temperature cycle (Scafetta, 2010). The Earth’s magnetic moment % decay over the past century reflects 30 -year weakening-trends and 30-year strengthening-trends of solar magnetic field, exhibiting the same periods (60-years) well correlated to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). In addition, magnetic trends exhibit 3 smaller inflection changes during the 30-year trends which appears correlated: (i) with the 9.1-year Moon orbital cycle and (ii) with El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) patterns overprinted with the 22-year Hale Cycle, more closely associated with a Jupiter affect. Finally the MaddenJulian Oscillation (MJO) 40-day power-spectrum correlates with the period in which Earth experiences a complete solar rotation and interestingly also a north-south oscillation of earthquakes along the Western Pacific rim (Krishnamurti, 2009). A review of the literature indicates that El Niño’s have 6-month earthquake precursors (Walker, 1995). In addition the Nation Earthquake information Center database reveals that large 9.0+ earthquakes only occur along the 30-year cooling trend during solar magnetic field strengthening. During this same period Earth also experiences electromagnetic (e.m.) induction charging, mostly from southern plasma ring-currents coupled to telluric currents in the ridge encircling Antarctica. This transformer effect from the south-pole exerts climate control over the planet via aligned tectonic vortex structures along the Western Pacific rim, electrically connected to the core. This is consistent with the “Earth Endogenous Energy” theory (Gregori, 2002 – Earth as a rechargeable battery/capacitor).

Link to full paper:http://worldnpa.org/climate-oscillations-mjo-enso-pdo-considered-with-validation-of-earth-endogenous-energy-theory/

- published: 29 Jun 2015

- views: 437

close fullscreen

- Playlist

- Chat

close fullscreen

- Playlist

- Chat

2:34

orbital period of a satellite

published: 28 Mar 2012

orbital period of a satellite

orbital period of a satellite

- Report rights infringement

- published: 28 Mar 2012

- views: 6058

10:53

Orbital Period of the Moon

Use Newton's version of Kepler's 3rd law to calculate the orbital period of the moon.

published: 12 Feb 2010

Orbital Period of the Moon

Orbital Period of the Moon

- Report rights infringement

- published: 12 Feb 2010

- views: 4289

2:39

[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284

BMS event [ノンジャンル] AUTOPLAY

published: 29 May 2012

[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284

[BMS]Orbital Period - 8284

- Report rights infringement

- published: 29 May 2012

- views: 498

2:36

bms Orbital Period - Photon Belt

끵끵

published: 21 Jul 2013

bms Orbital Period - Photon Belt

bms Orbital Period - Photon Belt

- Report rights infringement

- published: 21 Jul 2013

- views: 458

5:10

Orbital Period of Earth

published: 08 Mar 2016

Orbital Period of Earth

Orbital Period of Earth

- Report rights infringement

- published: 08 Mar 2016

- views: 34

2:45

[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY

published: 23 Dec 2012

[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY

[BMS] ◆◆12 Orbital Period -Photon Belt- AUTOPLAY

- Report rights infringement

- published: 23 Dec 2012

- views: 1847

2:44

[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY

published: 03 Jul 2012

[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY

[BMS] ▼2 Orbital Period [ANOTHER] AUTOPLAY

- Report rights infringement

- published: 03 Jul 2012

- views: 350

7:06

Orbital Period of the Sun in the Milky Way

I use our knowledge of the Milky Way rotation speed and our location to work out what the ...

published: 06 Oct 2011

Orbital Period of the Sun in the Milky Way

Orbital Period of the Sun in the Milky Way

- Report rights infringement

- published: 06 Oct 2011

- views: 5847

14:18

Orbital Period - Brain Waves

The orbital period is the time required to complete one orbit. Orbit period is easy to ca...

published: 23 Jun 2016

Orbital Period - Brain Waves

Orbital Period - Brain Waves

- Report rights infringement

- published: 23 Jun 2016

- views: 4

1:42

Satellite Orbital Period vs Radial Distance

Demonstrates the period (T) of a satellites orbit as a function of its earth radial distan...

published: 17 Mar 2010

Satellite Orbital Period vs Radial Distance

Satellite Orbital Period vs Radial Distance

- Report rights infringement

- published: 17 Mar 2010

- views: 811

close fullscreen

- Playlist

- Chat

1:32

Orbital Period & Rotation Period

How long does the Earth and the other planets finish orbiting around the Sun?

MERCURY - 88...

published: 26 Jun 2016

Orbital Period & Rotation Period

Orbital Period & Rotation Period

- Report rights infringement

- published: 26 Jun 2016

- views: 21

1:28

A year is the orbital period of the Earth moving in its orbit around the Sun.

Use this material to improve your skills of listening, reading and speaking. Practice ever...

published: 17 Jun 2016

A year is the orbital period of the Earth moving in its orbit around the Sun.

A year is the orbital period of the Earth moving in its orbit around the Sun.

- Report rights infringement

- published: 17 Jun 2016

- views: 32

2:36

[Artcore]8284 - Orbital Period

published: 06 Jun 2016

[Artcore]8284 - Orbital Period

[Artcore]8284 - Orbital Period

- Report rights infringement

- published: 06 Jun 2016

- views: 89

0:18

Orbital evolution in Kepler-223

These animations show approximately 200,000 years of orbital evolution in the Kepler-223 p...

published: 11 May 2016

Orbital evolution in Kepler-223

Orbital evolution in Kepler-223

- Report rights infringement

- published: 11 May 2016

- views: 9511

7:05

PXR047 / Pollux Beta - Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

Buy from Beatport: https://pro.beatport.com/label/pollux-records/14760

Contact : polluxre...

published: 11 Apr 2016

PXR047 / Pollux Beta - Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

PXR047 / Pollux Beta - Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

- Report rights infringement

- published: 11 Apr 2016

- views: 27

7:06

Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

Pollux Beta - Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix) - Pollux Records

Th...

published: 04 Mar 2016

Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

Pollux Beta: Orbital Period : 589 Days (Original Mix)

- Report rights infringement

- published: 04 Mar 2016

- views: 5

3:50

Elite Dangerous planet's orbital moving simulation in different flying modes

Planets are moving smoothly in supercruise mode and in shorts dashes in normal flying mode...

published: 10 Feb 2016

Elite Dangerous planet's orbital moving simulation in different flying modes

7:09

Mass of Sagittarius A* from SO-2 (S2) Star's Orbital Parameters

Sagittarius A* is a suspected supermassive black hole located at the center of our Milky W...

published: 05 Feb 2016

Mass of Sagittarius A* from SO-2 (S2) Star's Orbital Parameters

Mass of Sagittarius A* from SO-2 (S2) Star's Orbital Parameters

- Report rights infringement

- published: 05 Feb 2016

- views: 79

close fullscreen

- Playlist

- Chat

24:21

Molecular Orbital Theory IV: Period 2 Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules

Molecular orbital diagrams of Li2, Be2, B2, C2, N2, O2, F2, and Ne2. Long winded video, b...

published: 07 Aug 2011

Molecular Orbital Theory IV: Period 2 Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules

Molecular Orbital Theory IV: Period 2 Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules

- Report rights infringement

- published: 07 Aug 2011

- views: 157230

66:01

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens - Konstantin Batygin ...

published: 16 Apr 2015

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens

Viewing Solar System Orbital Architecture through an Extrasolar Lens

- Report rights infringement

- published: 16 Apr 2015

- views: 5570

49:09

Lec 22: Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, and Maneuvers | 8.01 Classical Mechanics (Walter Lewin)

Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, Change of Orbits, and the famous passing of a Ham Sandwi...

published: 11 Dec 2014

Lec 22: Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, and Maneuvers | 8.01 Classical Mechanics (Walter Lewin)

Lec 22: Kepler's Laws, Elliptical Orbits, and Maneuvers | 8.01 Classical Mechanics (Walter Lewin)

- Report rights infringement

- published: 11 Dec 2014

- views: 17839

20:58

Kerbal Space Program - Part 2 - Orbital Docking, Transfers and Trigonometry (Docking 101)

Join me on Twitter: http://twitter.com/WhatDaMath

Hello and welcome to What Da Math.

In ...

published: 06 Dec 2014

Kerbal Space Program - Part 2 - Orbital Docking, Transfers and Trigonometry (Docking 101)

Kerbal Space Program - Part 2 - Orbital Docking, Transfers and Trigonometry (Docking 101)

- Report rights infringement

- published: 06 Dec 2014

- views: 431

114:47

KEPLER 186F Discovered And Life After Earth - 2016 Documentary - 2 Hours

Kepler-186f is an exoplanet orbiting the red dwarf Kepler-186,[4][5][6] about 490 light-ye...

published: 10 Jun 2016

KEPLER 186F Discovered And Life After Earth - 2016 Documentary - 2 Hours

KEPLER 186F Discovered And Life After Earth - 2016 Documentary - 2 Hours

- Report rights infringement

- published: 10 Jun 2016

- views: 201

55:11

【東方】 交響曲「幻想郷世界」

ニコニコ動画から転載

http://www.nicovideo.jp/watch/sm16495241

東方アレンジメドレー100曲です

published: 19 Aug 2012

【東方】 交響曲「幻想郷世界」

【東方】 交響曲「幻想郷世界」

- Report rights infringement

- published: 19 Aug 2012

- views: 105995

30:37

BUMP OF CHICKEN PONTSUKA!! 2007年4月8日

BUMP OF CHICKEN

バンプオブチキン

ポンツカ

藤原基央さん28歳誕生日回

記念すべきorbital periodですね

published: 10 Sep 2015

BUMP OF CHICKEN PONTSUKA!! 2007年4月8日

BUMP OF CHICKEN PONTSUKA!! 2007年4月8日

- Report rights infringement

- published: 10 Sep 2015

- views: 4622

24:37

Class 10+1, Chapter 6, Question 14, Orbital speed, Time period, Energy of satelite

Class 10+1, Chapter 6, Question 14, Orbital speed, Time period, Energy of satelite

published: 08 Aug 2015

Class 10+1, Chapter 6, Question 14, Orbital speed, Time period, Energy of satelite

Class 10+1, Chapter 6, Question 14, Orbital speed, Time period, Energy of satelite

- Report rights infringement

- published: 08 Aug 2015

- views: 26

32:27

The Black Knight Satellite 2014 new information

Black Knight also known as the Black Knight satellite is an alleged object orbiting Earth ...

published: 12 Oct 2014

The Black Knight Satellite 2014 new information

The Black Knight Satellite 2014 new information

- Report rights infringement

- published: 12 Oct 2014

- views: 1114770

38:51

Bruce Leybourne - Validation of Earth Endogenous Theory

Climate oscillations with periods ~20 and ~60-years, appear synchronized to Jupiter (12-ye...

published: 29 Jun 2015

Bruce Leybourne - Validation of Earth Endogenous Theory

Bruce Leybourne - Validation of Earth Endogenous Theory

- Report rights infringement

- published: 29 Jun 2015

- views: 437

Convention over, Clinton faces hacking, Trump criticism

Edit The Virginian-Pilot 30 Jul 2016

HARRISBURG, Pa. (AP) — A giddy if exhausted Hillary Clinton embarked on a post-convention Rust Belt bus tour just hours after becoming the first female presidential nominee of a major political party ... ....

Stephen Hawking Issues Warning For What Brexit Could Mean For The Human Species

Edit WorldNews.com 29 Jul 2016

Stephen Hawking has penned a thoughtful appeal for post-Brexit Britain to reconsider the role that wealth plays in society, warning that isolationism and envy could even lead to the end of the human species, Mashable reports. In a Guardian essay, the world-renowned physicist made the case for a more comprehensive and generous definition of wealth "to include knowledge, natural resources and human capacity." ... ....

Belgium arrests two men suspected of planning attack

Edit The Hindu 30 Jul 2016

The two, named as 33-year-old Nourredine H ... Seven houses searched ... No weapons or explosives were found. Keywords....

Wing part 'highly likely' from MH370, Australian officials say

Edit CNN 30 Jul 2016

(CNN)A large wing part recently found on a Tanzanian island "highly likely" came from missing Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, according to Australia's transport minister. The piece of debris was found in late June on Pemba Island, in the Indian Ocean near the mainland ... A piece of aircraft debris found on Pemba Island, just off Tanzania, in late June was analyzed in Australia ... MH370. Timeline of found parts. March. 2016. 1. Engine Cowling ... 2 ... 3....

« back to news headlines

NASA's getting ready to plunge a spacecraft deeper into the sun than ever before

Edit Business Insider 30 Jul 2016

NASA ... The Solar Probe Plus mission will start with the launch of a spaceship that will complete 24 orbits of the sun ... The three closest orbits will be just under 4 million miles from the Sun’s surface — that’s seven times closer than any spacecraft has ever come to our neighborhood fireball. That close to the sun, the spacecraft will face 500 times as much solar intensity as a spacecraft orbiting Earth ... NASA ... Loading video... ....

U.S. growth barely rises

Edit Times Union 30 Jul 2016

The April-June quarter was the third consecutive period in which the economy advanced at less than a 2 percent annual rate, the weakest stretch in four years. The new economic data underscores the continuing frustration about the current growth cycle, which has now gone on for seven years — longer than most economic upswings — but which has repeatedly failed to break out into a higher orbit....

Quantum theory and Einstein's special relativity applied to plasma physics issues

Edit Science Daily 30 Jul 2016

Among the intriguing issues in plasma physics are those surrounding X-ray pulsars -- collapsed stars that orbit around a cosmic companion and beam light at regular intervals, like lighthouses in the sky. Physicists want to know the strength of the magnetic field and density of the plasma that surrounds these pulsars, which can be millions of times greater than the density of plasma in stars like the sun ... ....

French Court finds that Luc Besson’s Lockout copied Escape From New York

Edit The Verge 30 Jul 2016

... was offered a pardon if he would rescue the president’s daughter (Maggie Grace), who was being held captive after a prison riot in an orbital prison....

Six-year-old from Oman born with Crouzon Syndrome given new lease of life at Fortis

Edit The Times of India 30 Jul 2016

Dr Gagan Sabharwal, Maxillofacial Surgeon, Department of Dentistry and Maxillofacial Surgery and Dr Amitabh Singh, Consultant, Cosmetic & Plastic Surgery, Fortis Memorial Research Institute stated that, "After a consolidation period of four days following the surgery performed at FMRI, the mid face and upper jaw was pulled forward @ 1 mm a day....

Broncos Training Camp Takeaways: Day 2 (Denver Broncos)

Edit Public Technologies 30 Jul 2016

-- If you've clicked around Broncos-related social media or this site, you know about Jordan Taylor's circus catch during the one-on-one period ... His catch in the one-on-one period is as spectacular as anything in recent memory from a training-camp practice ... Lynch missed a golden opportunity for a deep connection when his pass to Taylor in the team period hung up a bit too long ... He also caught a pass from Lynch in the second team period....

HCL Infosystems Q1 loss narrows to Rs 35.7 cr

Edit The Times of India 30 Jul 2016

As required under Section 2 (41) of the Companies Act 2013, during the previous period, the company and its subsidiaries have changed its accounting period from July-June to April-March and therefore, the previous accounting period comprised of results for nine months period ended March 31, 2016, it said....

DMRC to help run Noida line

Edit The Times of India 30 Jul 2016

The assistance for operations and maintenance services would be rendered during the pre-commercial operation period of the NMRC and three-year post-commercial operation period too ... Explaining the details of the MoU, officials said that during the pre-commercial operation period, the permanent or contractual manpower requirements will be advised and recruited by the DMRC in consultation with the NMRC....

World energy giant Exxon Mobil reports quarterly loss

Edit Xinhua 30 Jul 2016

oil company, reported on Friday a profits loss of nearly 60 percent in its second quarter of this year as compared with the same period of last year ... same period of last year, Exxon Mobil said in a statement issued on Friday....

Nestle India second quarter profit at Rs 231 crore

Edit Deccan Chronicle 30 Jul 2016

Net sales of the company during the quarter under review were up 16.66 per cent to Rs 2,256.09 crore as against Rs 1,933.84 crore of the year-ago period, Nestle said in a BSE filing ... For the first half of the year, Nestle's net profit was up 91.43 per cent to Rs 489.84 crore as against Rs 255.88 crore of the corresponding period of 2015....

Brazil's Embraer registers over one-bln-USD deficit

Edit Xinhua 30 Jul 2016

dollars) in the second quarter of 2016 ... dollars) it obtained in profit during the same period in 2015 ... dollars) in the second quarter ... dollars) from the same period in 2015 ... dollars) in the first half of 2016, 77.3 percent less than the same period of 2015 ... dollars, 4.3 percent lower than the same period in 2015 and the same as the the first quarter of 2016 ... The investment estimations remain the same for all of 2016 ... ....

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Next page »