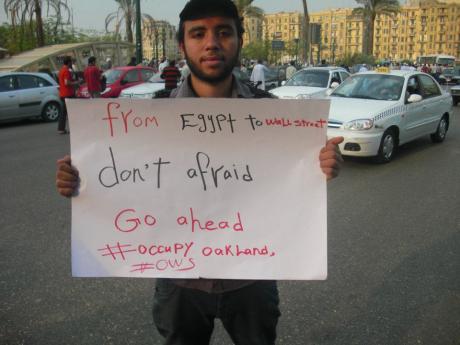

Wendell Hassan Marsh on the links between the Wisconsin protests, the Egyptian Revolution and the Occupy movement.

Former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak had already stepped down, following a popular movement that established a micro-republic, the Gumhuriyyah el-Tahrir (Republic of Liberty), which contradicted the pervading logic of the international economic system. And now protesters in Wisconsin were occupying the state house to prevent the passing of legislation that would effectively suspend bargaining rights for public workers. Sitting in a Washington newsroom, we needed a headline. I very quickly suggested something along these lines: “Middle East unrest spreads to the Midwest.” I got a side eye. After all, how could a free and open society, the democratic society, be taking its cues from, of all places, Egypt, an antique land with backward ways, Islamic fundamentalists, and Arab dictators? The editors went with a more modest title.

However, for many in the Arab world, the connection was not lost for a minute. They saw in the occupation of the Wisconsin State Capitol the same spirit that was present in Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation: the refusal to accept the financial order’s demand to obliterate decades of progressive struggle and negotiation.

Maybe my own time in Cairo made me see the easy connection that my editors missed. I lived there for a almost a year and a half on the largess of the American government. The conditions of my presence were a reminder of the structural inequalities of the global system. Any old American can arrive to the airport without a visa, little training in any useful domain and quickly find gainful employment and a life of comfort. An Egyptian, however, even with years of education, has to struggle to make a living.

As many set out today to occupy everything, let us take a moment to remember the real origins of this global movement and allow it to guide our ongoing politics.

Deep in the land of Hannibal the Carthaginian, who once challenged the power of another global empire, Bouazizi was born to a construction worker, living his entire life in Sidi Bouzid, an agrarian town. The 26-year-old scraped together an existence for himself and a large family by selling fruit. Relatively speaking, he did well to have even that hustle, as the New York Times reported that unemployment reaches as high as 30% in his area. There was a nearby factory, but that only pays around $50 a month. Even the college educated were heading to the coast, where they too struggled with underemployment.

A veteran fruit vendor, Bouazizi was used to the authorities that policed the fruit stands. Sometimes he paid a fine, other times a bribe. But on the morning of December 17, Bouazizi refused to do either. He also refused an attempted confiscation of his fruit, commodities that are often bought on credit by the para-legal vendors. The representative of the state eventually won the first battle. Beaten and humiliated, Bouazizi quickly tried redressing his grievances at the governor’s office, requesting that, at the least, his scale be returned. Ignored at the governor’s, he was reported to ask, “how do you expect me to make a living?” He set himself ablaze and ignited a global movement.

Protests started hours after the incident. Bouazizi’s family and friends threw coins at the governor’s gate. “Here is your bribe,” they yelled. As the unrest grew, police started to beat protesters, firing tear gas and eventually bullets. But the spirit wouldn’t be stifled. Organized labor joined in the struggle, identifying the central problem as economic. After all, it was global capital that had denied Bouazizi and his supporters their dignity; it extracted surplus value from human objects down to the last drop of blood.

Former colonial power France offered to lend a hand with its security savoir-faire. Or maybe they would have just hired a private firm to handle the contract. Later acknowledging the misstep, Sarkozy tried to justify his government’s support of the authoritarian regime with revealing, if trite, arguments. “Behind the emancipation of women, the drive for education and training, the economic dynamism, the emergence of a middle class, there was a despair, a suffering, a sense of suffocation. We have to recognise that we underestimated it,” Sarkozy said in a press conference.

Sarkozy underestimated the effect that the “economic dynamism” of the ruling elite had on the majority of the country. He underestimated the diminished economic prospects that resulted from Tunisia’s decreased agricultural and manufacturing exports to Europe. He underestimated the Tunisian people’s reaction in the face of potential annihilation by economic violence.

The movement quickly spread to nearby Egypt, where conditions have been even worse, the socio-economic divide between the top 1% and the rest even more dramatic. Several self-immolations occurred throughout the country, prompting the Cheikh of al Azhar, the most respected institution in the Sunni Islamic world, to issue a fatwa against the practice. Youth with degrees but without jobs started to occupy Tahrir Square, to call for the dignity that global neoliberal policies had denied them. They took the recent tactics of Egypt’s young but growing labor movement and added others.

When Mubarak, whose 30-year reign had been marked by the opening of the country to Western business interests, started to crack down on the protesters as the empire’s strong man, the people said he had to go. The public began to protest against dictatorship, but only insofar as they were protesting the global economic empire.

Somehow a popular narrative has emerged in our media that the Arab spring protested against dictatorship, against murderous regimes. These popular struggles have been reduced to rebellions against the villainies of a Qaddafi, an Assad, a Saleh.

But the Arab Spring started as a protest against global finance and its henchmen. Almost across the board, protesters claiming public space were demanding mostly economic reforms. It was only after Arab dictators, whose decennial rules offered up their countries to the jaws of the global market, started to repress this popular struggle with violence, that dictatorship became the target of regime change.

Occupy Wall Street and the subsequent Occupy movement were initiated in the same spirit of economic justice. Zuccotti Park, ironically taken and renamed Liberty Plaza by its occupiers, is a micro-republic where the logic of empire doesn’t work. People take pride in discomfort, in being arrested and working for free. Altruism has become normative and hierarchy repugnant. To be sure, there is inner dissent and struggle within the body politic of the micro-republic. Nevertheless, the audacity to live a utopian practice has become liberating in itself.

Yet this movement can’t content itself with granting young people the right to take on more debt to live the lives the world can’t sustain, or reforming the way candidates fund their campaigns. The despotism that western powers decry in the name of human rights is a symptom of a wider system of economic exploitation, which at home manifests itself in the attack on the American working and middle class. They are connected.

The repressive measures states use against their own populations has also been imported from the Middle East. A recent post by Max Blumenthal connects the dots behind recent alarming examples of social control and police militarization:

The police repression on display in Oakland reminded me of tactics I witnessed the Israeli army employ against Palestinian popular struggle demonstrations in occupied West Bank villages like Nabi Saleh, Ni’lin and Bilin. So I was not surprised when I learned that the same company that supplies the Israeli army with teargas rounds and other weapons of mass suppression is selling its dangerous wares to the Oakland police. The company is Defense Technology, a Casper, Wyoming based arms firm that claims to “specialize in less lethal technology” and other “crowd management products.” Defense Tech sells everything from rubber coated teargas rounds that bounce in order to maximize gas dispersal to 40 millimeter “direct impact” sponge rounds to “specialty impact” 12 gauge rubber bullets.

One veteran of the war in Iraq knows the effects of the police-sponsored violence firsthand. After being hit by a tear gas canister launched by the Oakland Police Department, Scott Olsen suffered a fractured skull and a swollen brain. As though that were not enough, video footage shows a police officer throwing a flash bang grenade next to the bloodied man to disperse the crowd of people coming to his aid. But such police brutality is nothing new in Oakland, home of a radical black politics that has struggled against structural economic and physical violence against the working class, the poor, and minorities.

We should remember that the politics forged by the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s and 1970s made deep ties with the anti-imperial projects of North Africa, the hotbed of today’s vanguard movement. Algeria made the Panther headquarters in Oakland their embassy, providing a sort of diplomatic shield against police surveillance. When Eldridge Cleaver went into exile, Algeria hosted him and the international section of the party. A chapter was also created in Cairo, then, a nerve center for the world wide freedom struggle.

Much is riding on the direction of the Occupy movement in America. While visiting the Wall Street occupiers, two of Tahrir’s leading activists emphasized the importance of the Occupy movement for the renewal of the Arab Spring. To Americans who asked how they could help the ongoing Egyptian struggle, Asmaa Mahfouz replied, “get your revolution done. That’s the biggest help you can give us.” What Mahfouz was counting on was the possibility that struggles in the United States could pressure the government to cut off the $1.3 billion yearly payments that sustain Egypt’s military.

Long-time activist Ahmad Maher reminded the crowd of the immense task the Arab Spring confronted, and which activists around the world still confront. An American asked him the most fundamental question: “how do you overthrow a system?” Speaking as a grassroots political organizer who has been on the Egyptian street for years, Maher replied, “It’s easier to overthrow a dictator than an entire system.”

There is a reason that the Occupy movement does not have a singular message, tied to one political body; its success or failure will lie in the degree to which it changes everything.

- Printer-friendly version

- Login or register to post comments

Can comment on articles and discussions

Can comment on articles and discussions