- Order:

- Duration: 3:06

- Published: 03 Oct 2010

- Uploaded: 20 Oct 2010

- Author: Bianx81795

Cone cells, or cones, are photoreceptor cells in the retina of the eye that are responsible for color vision; they function best in relatively bright light, as opposed to rod cells that work better in dim light. Cone cells are densely packed in the fovea, but gradually become sparser towards the periphery of the retina.

A commonly cited figure of six million in the human eye was found by Osterberg in 1935. Oyster's textbook (1999) cites work by Curcio et al. (1990) indicating an average closer to 4.5 million cone cells and 90 million rod cells in the human retina.

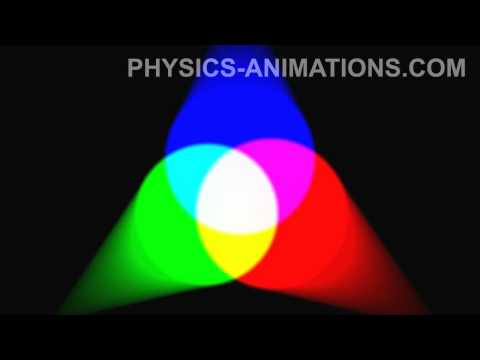

Cones are less sensitive to light than the rod cells in the retina (which support vision at low light levels), but allow the perception of color. They are also able to perceive finer detail and more rapid changes in images, because their response times to stimuli are faster than those of rods. Because humans usually have three kinds of cones with different photopsins, which have different response curves and thus respond to variation in color in different ways, they have trichromatic vision. Being color blind can change this, and there have been reports of people with four or more types of cones, giving them tetrachromatic vision.

The color yellow, for example, is perceived when the L cones are stimulated slightly more than the M cones, and the color red is perceived when the L cones are stimulated significantly more than the M cones. Similarly, blue and violet hues are perceived when the S receptor is stimulated more than the other two.

The S cones are most sensitive to light at wavelengths around 420 nm. However, the lens and cornea of the human eye are increasingly absorptive to smaller wavelengths, and this sets the lower wavelength limit of human-visible light to approximately 380 nm, which is therefore called 'ultraviolet' light. People with aphakia, a condition where the eye lacks a lens, sometimes report the ability to see into the ultraviolet range. At moderate to bright light levels where the cones function, the eye is more sensitive to yellowish-green light than other colors because this stimulates the two most common of the three kinds of cones almost equally. At lower light levels, where only the rod cells function, the sensitivity is greatest at a blueish-green wavelength.

Cone cells are somewhat shorter than rods, but wider and tapered, and are much less numerous than rods in most parts of the retina, but greatly outnumber rods in the fovea. Structurally, cone cells have a cone-like shape at one end where a pigment filters incoming light, giving them their different response curves. They are typically 40-50 µm long, and their diameter varies from 0.5 to 4.0 µm, being smallest and most tightly packed at the center of the eye at the fovea. The S cones are a little larger than the others.

Photobleaching can be used to determine cone arrangement. This is done by exposing dark-adapted retina to a certain wavelength of light that paralyzes the particular type of cone sensitive to that wavelength for up to thirty minutes from being able to dark-adapt making it appear white in contrast to the grey dark-adapted cones when a picture of the retina is taken. The results illustrate that S cones are randomly placed and appear much less frequently than the M and L cones. The ratio of M and L cones varies greatly among different people with regular vision (e.g. values of 75.8% L with 20.0% M versus 50.6% L with 44.2% M in two male subjects).

Like rods, each cone cell has a synaptic terminal, an inner segment, and an outer segment as well as an interior nucleus and various mitochondria. The synaptic terminal forms a synapse with a neuron such as a bipolar cell. The inner and outer segments are connected by a cilium. The inner segment contains organelles and the cell's nucleus, while the outer segment, which is pointed toward the back of the eye, contains the light-absorbing materials.

Like rods, the outer segments of cones have invaginations of their cell membranes that create stacks of membranous disks. Photopigments exist as transmembrane proteins within these disks, which provide more surface area for light to affect the pigments. In cones, these disks are attached to the outer membrane, whereas they are pinched off and exist separately in rods. Neither rods nor cones divide, but their membranous disks wear out and are worn off at the end of the outer segment, to be consumed and recycled by phagocytic cells.

The response of cone cells to light is also directionally nonuniform, peaking at a direction that receives light from the center of the pupil; this effect is known as the Stiles–Crawford effect.

Category:Photoreceptor cells Category:Eye Category:Human cells Category:Neurons

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.