“You must refrain from thinking controversial thoughts out loud…” the Chair of Board of Governors told University of British Columbia (UBC) President, Dr. Arvind Gupta in May, 2015. Shortly afterward, UBC announced that Dr. Gupta, UBC’s first non-white President, had stepped down after serving only thirteen months of a five-year term. The year 2015 also marked the 100-year anniversary of UBC and Centennial celebrations, along with Dr. Gupta’s sudden departure, prompted my reflections here.

(Dr. Arvind Gupta, Former President of University of British Columbia,

image source)

The circumstances leading to Dr. Gupta’s mystifying and unprecedented exit from the UBC Presidency were not immediately disclosed and the university became embroiled in a public relations fiasco fueled by speculation. One UBC professor of Mathematics, Dr. Nassif Ghossoub, called for the resignation of the Chair of the Board of Governors over the “botched” announcement of the resignation. At the Sauder School of Business, Dr. Jennifer Berdahl, an expert in gender and diversity, wrote on her blog that the ex-President lost “the masculinity contest among leadership at UBC, as most women and minorities do at institutions dominated by white men” only to be chided by the Chair of the Board of Governors for this observation. Dr. Berdahl then publicly exposed what she experienced to be an attempt by the Chair to silence her and thus undermine her academic freedom.

Unlike 1915 when the university was founded, the dynamics of leadership were different as UBC entered its 100th year under a woman President, Dr. Piper. She had served in this position before (1997-2006) and was hastily reappointed for one year upon the untimely departure of Gupta. In a statement welcoming students, staff, instructors and faculty into the centennial year of the University of British Columbia, Piper said:

“We are as committed to our core mission of learning and research as were our founders in 1915, and this centennial year will give us the opportunity to show that the spirit of intellectual inquiry is alive and well at UBC as we reach new heights in innovation and discovery.”

(Dr. Martha Piper, Interim President, University of British Columbia,

image source)

Of course, what is left unsaid in Dr. Piper’s remarks is that the university’s 1915 ‘core mission’ as conceived by its founders relied upon the dispossession of the unceded traditional territories of the Musqueam and Coast Salish peoples. This ‘core mission’ placed the university at the centre of Eurocentric knowledge production and of fostering the emergent Canadian elite in the province, and indeed, the country. As such, the institution reflected, and was reflective of, the racial and imperial policies of a colonial-settler state and society. Moreover, the migration and settlement policies of the period sought to increase the presence and power of ‘preferred’ European ‘races’ while containing the permanent settlement of the ‘non-preferred’ races of Asia and Africa. In other words, UBC’s ‘core mission’ was of a piece with the practices that were to produce Canada as a ‘white man’s country.’

“It looks like a whitewash” was a comment I heard with regard to Dr. Gupta again and again in the community, as well as from a number of colleagues not particularly attuned to the politics of race or diversity. The high-handed replacement of UBC’s first President of colour with a white, albeit highly qualified and reputed, woman under secretive conditions raised many questions, not the least about the vexed politics of race, diversity, gender and equity at the university. These politics, of course, reach well beyond the level of optics in shaping intellectual and institutional life. The case of Dr. Gupta reveals that if the gender politics at UBC have shifted during its history, these now serve its racialized power structure. Indeed, UBC is becoming whiter at its Centennial even as this whiteness is contested in the world in which the university functions. Unfortunately, like 1915, white hegemony remains pretty resilient at UBC.

‘Race Culture’ Structures Life in the Canadian Academy

University campuses across North America have been in a state of heightened turmoil in the last decade. Debates and struggles sparked by the racial, gender, sexual and colonial/imperial politics that shape the academy are no less explosive now than they were at the height of the protest movements of the 1960s. Public attention in Canada has focused mainly on protests against anti-Black racism in the US, from Yale to Mizzou, but much less reported is the fact that protests against anti-Black, anti-Indigenous and other forms of racism are also being organized at Canadian universities. While protests against austerity measures and the ‘rape culture’ on campuses receives national (if intermittent) public attention – as with the rape chants and sexual assaults at UBC and the online posting of misogynist comments by a group of dentistry students at Dalhousie University – the ‘race culture’ that structures life in the Canadian academy receives far less public or scholarly attention.

(Canadian students protest, image source)

The glaring absence of Indigenous scholars and scholars of colour in leadership at UBC has been documented by the administration itself, as has been its culture of institutional whiteness. A 2013 report, Inclusion: A Consultation on Organizational Change to Support UBC’s Commitment to Equity and Diversity, commissioned by then President Toope found a “lack of representation of racialized groups in senior positions and on committees, a lack of safe spaces for racialized groups, as well as the persistence of Eurocentric norms in the evaluation of scholarship and work performance.” The report concluded bluntly, “UBC’s leadership and therefore its key decision-makers are white.”

UBC’s response to this report – which tied equity to diversity and linked both to race – was to ignore its findings on race, delink diversity from equity and link a generic approach to equity with ‘inclusion’. In this, UBC provided a textbook example of what has been theorized in the scholarly literature as the ‘non-performativity’ of diversity and anti-racism policies.

Sara Ahmed, in her empirical study of diversity work in universities, found that the writing of diversity statements, policies and reports is taken by administrations to be the ‘doing’ of the work of redressing inequalities of race. These policies and statements thus do not actually accomplish what they claim. They are ‘non-performative’ in that they do not translate into the action required to bring about the necessary change to make the institution diverse and anti-racist.

At UBC, the actionable information presented by the report was likewise not taken up to redress the lack of diversity and racial inequality in its leadership. Instead, this knowledge became calibrated to a race-blind approach that allowed for the enhancement of gender inclusion but deepened the racial inequality in the university’s institutional mechanisms. Put differently, the institution acted on the report to make itself whiter.

(image source)

Such institutional investments in whiteness shape the context in which the Gupta affair has played out. The crisis ignited by his unseemly departure – GuptaGate, as it is dubbed by some – deepened during the fall 2015 term with the administration’s (mis)handling of other cases related to gender, sex and race, some of which came to public attention. These included an investigation into the infringement of Dr. Jennifer Berdahl’s academic freedom, which led to the resignation of the Chair of the Board of Governors, but no apology from the university; and the institution’s (non)response to sexual assault cases on campus reported by women students, featured in a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation documentary.

The University Forced to Release Documents on ‘GuptaGate’

UBC finally broke its silence about the Gupta debacle with the release of the documents in late January (2016) in response to several Freedom of Information requests. The documents were highly redacted, but upon their release, online activists downloaded a treasure trove of uncensored attachments that were apparently released in error. These attachments made for intriguing reading for they revealed just how fractious the relationship between Dr. Gupta and some members of the Board of Governors (the majority of whom are political appointees) had become. They also pointed to serious violations of transparency, accountability and fair treatment at this publicly funded institution. Leaked statements from powerful members of the Board of Governors charged Dr. Gupta with exceeding his authority, acting in a manner unbefitting a university President, and generally being inept, divisive, confrontational and ineffectual.

The quote with which I began (“… you must refrain from thinking controversial thoughts aloud….”) provides a sense of the tone adopted by the Chair of the Board in his communication with the President. In contrast, Dr. Gupta’s response revealed a collegial and measured response to the very many criticisms leveled at him both personally and professionally. His emphasis was on the professional nature of their working relationships and on what he still clearly took to be their shared objectives.

Upon UBC’s release of these documents, Dr. Gupta spoke publicly about how his vision for transforming UBC into a 21st Century institution generated resistance from some sectors within the institution. Without specifying the exact scope and nature of the change he envisioned, or the particulars of the conflicts with the Board of Governors, he described how he found out about secret meetings held by an ad hoc committee of the Board. In Dr. Gupta’s estimation, “This group had only one intention… They decided they didn’t want me.” Eventually Dr. Gupta felt there remained no alternative but for him to resign if UBC was to be protected from further internal strife.

There have been suggestions that the conflicts between some members of the Board of Governors and Dr. Gupta may have included the former President’s attempt to restructure the top level of the administration with an emphasis on fiscal responsibility, accountability and transparency, and a shift of resources to faculty and students to support teaching, research and experiential learning. There is also speculation that Dr. Gupta’s ambitious attempts to resolve older “thorny and unfinished issues” – which included “a mishandled Athletics file, a controversial ‘Vantage College’, disagreements over copyrights, a faulty housing plan that never got off the ground, as well as various pre-approved big ticket capital expenditures” – were not well-received. The ex-President’s experience has been described as a “nightmare”, it raised concerns about “bullying and harassment” for at least one of his close colleagues. Moreover, the role of political appointees in running the university has sparked further public debate about the involvement of the provincial government in UBC’s internal workings. The refusal of the UBC administration to respond to these substantive issues has kept the speculation and rumors alive and growing.

(image source)

Three Lessons about Race and Gender from the Crisis at UBC

What, then, are the lessons of this ‘teachable’ moment that is the crisis of legitimacy at UBC? As a member of the UBC faculty who has worked for over a decade and a half to promote critical race feminist and anti-colonial studies and advocate for the leadership of faculty, sessionals and students of colour and of indigenous ancestry, I find this current imbroglio reveals a number of important insights into how the politics of race, gender and coloniality are currently being reconstituted at one of Canada’s leading academic institutions.

- White Hegemony Takes Work. The crisis at CBC demonstrates just how much work it takes to assert white hegemony within the university. Instead of a remnant of a regrettable past that has been transcended, the production and maintenance of this hegemony requires active, dynamic and ongoing efforts at the highest administrative levels. The present crisis demonstrates how those in positions of leadership work to contain the direction of change in order to enhance their own status and access to power. Most significant from my perspective, the departure of the first President of colour, his replacement by a white President, the announcement and press statements by UBC, and the release of documents, all took place without the word ‘race’ entering the public debates and discussions in any meaningful manner. If ‘race’ has been made invisible in this matter, so too has the ‘whiteness’ that is treated as the normative state of the institution.

- Disenfranchisement and Appropriation are Crucial Strategies. Producing this institutional whiteness requires the ongoing, active and collective disenfranchisement of underrepresented racialized groups and the appropriation of their creativity, labour and expertise. The UBC example shows how, despite the accomplishments of Dr. Gupta, even in the very neo-liberal terms set by the university, he was denied procedural fairness and due process as stipulated in his contract. And, despite the supposed urgency for his departure, the UBC leadership continued to state their commitment to move ahead with the strategic plan that he had envisioned, presumably with the resources he helped bring to UBC. This suggests there was no significant flaw in his strategic vision or abilities, only with the man himself. The university’s policies, procedures, statements and reports that hold the promise of fair and equitable treatment are thus shown to be set aside on the basis of nothing more than the preferences, choices and interests of the (white) leadership. The Gupta debacle demonstrates how little the principles of fair and equal treatment, transparency and accountability actually impact on the making of such decisions.

- White Women are the Main Beneficiaries of Equity Measures. The UBC crisis demonstrates how gender is put to work to advance institutional whiteness when the latter is destabilized. Of the four equity seeking constituencies, the greatest advances within the academy have been made in the area of gender equity, as Malinda Smith has found in her research. Significant, however, is that gender is read as white in the Canadian context, so that it is white women who have been the main beneficiaries of equity measures. Likewise at UBC, the treatment of gender continues to privilege white women, enabling them to corner the equity market by actively marginalizing women of colour faculty Situated at the forefront of ‘equity’ and ‘inclusion’ initiatives, gender (shorn of its intersections with other social relations, particularly race) now functions as a gatekeeper for the other equity seeking groups, Smith argues. Gender is thus a key site for the reconsolidation of a white hegemony that is deeply contested otherwise. In the present climate of local and global challenges to racial/imperial discourses of western superiority, promoting race-blind approaches to gender helps restabilize whiteness by containing and impeding the transformative potential of anti-colonial and anti-racist gender politics.

The UBC crisis is far from resolved. Even as the Board of Governors rushes ahead to consolidate what many define publicly as a coup against Dr. Gupta with its search for a replacement President, the Faculty Association and the AMS Student Society have called for an external investigation into the Board’s governance practices. They have also demanded the suspension of the search for a new President until such an investigation is complete. These developments have been followed by the release of a public statement from the Deans throwing their support behind the Board of Governors and the Presidential search committee. How and when the present standoff between the university’s leadership and its faculty and students will end remains to be seen.

The mess upending UBC’s centennial celebrations can be anticipated to keep feeding the tensions and upheavals in campus life, and the need for the administration to respond to the substantive matters raised by faculty, students and the general public becomes more pressing by the day. Even the most cursory of observations reveals that UBC’s leadership and its structures of authority reflect neither the demographic make-up nor the social and cultural environment in which the university operates, that it is not representative of the communities it claims to serve.

The making of UBC into a whiter institution will have major and far-reaching repercussions; this larger crisis affects not only the university’s governance, it sets back the cause of racial justice to which many of us are committed. That we have to speak out against the further entrenchment of white hegemony a century after UBC’s founding is a scandal.

~ Sunera Thobani is Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia. She is a co-founder of the cross-Canada network, Researchers and Academics of Colour for Equity (RACE), the former Director of the Centre for Race, Autobiography, Gender and Aging (RAGA) at UBC, and a former President of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women. Dr. Thobani is the author of Exalted Subjects: Studies in the Making of Race and Nation in Canada (University of Toronto Press, 2007), and coeditor of Asian Women: Interconnections (Canadian Scholars Press, 2005) and States of Race: A Critical Race Feminism for the 21st Century (Between the Lines, 2010). She is currently working on a book on Race and Coloniality in the Academy.

(Photo: Wiki-images)

(Photo: Wiki-images)

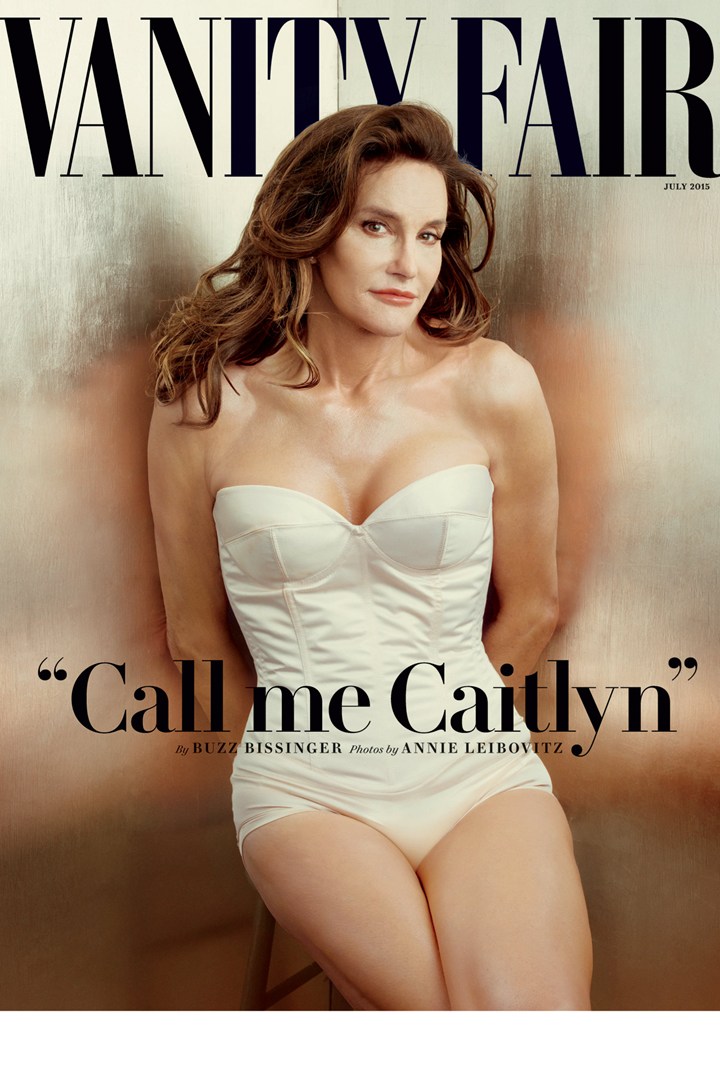

(Caitlyn Jenner for HM Sports,

(Caitlyn Jenner for HM Sports,