Posted by Mark Thoma on Thursday, April 14, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (8)

Robert Frank:

Why Luck Matters More Than You Might Think: ...chance plays a far larger role in life outcomes than most people realize. And yet,... Wealthy people overwhelmingly attribute their own success to hard work rather than to factors like luck or being in the right place at the right time.

That’s troubling, because a growing body of evidence suggests that seeing ourselves as self-made—rather than as talented, hardworking, and lucky—leads us to be less generous and public-spirited. It may even make the lucky less likely to support the conditions (such as high-quality public infrastructure and education) that made their own success possible. ...

The one dimension of personal luck that transcends all others is to have been born in a highly developed country. ... Being born in a favorable environment is an enormous stroke of luck. But maintaining such an environment requires high levels of public investment in everything from infrastructure to education—something Americans have lately been unwilling to support. Many factors have contributed to this reticence, but one in particular stands out: budget deficits resulting from a long-term decline in the United States’ top marginal tax rate. ...

A recent study by the political scientists Benjamin Page, Larry Bartels, and Jason Seawright found that the top 1 percent of U.S. wealth-holders are “extremely active politically” and are much more likely than the rest of the American public to resist taxation, regulation, and government spending. ... Surely it’s a short hop from overlooking luck’s role in success to feeling entitled to keep the lion’s share of your income—and to being reluctant to sustain the public investments that let you succeed in the first place.

And yet this state of affairs does not appear to be inevitable: Recent research suggests that being prompted to recognize luck can encourage generosity. ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Wednesday, April 13, 2016 at 08:46 AM in Economics |

Permalink

Comments (29)

Paul Krugman:

Why Monetarism Failed: Brad DeLong asks why monetarism — broadly defined as the view that monetary policy can and should be used to stabilize economies — has more or less disappeared from the scene, both intellectually and politically. As it happens, I wrote about essentially the same question back in 2010, inspired by the more or less hysterical pushback against quantitative easing. I thought then and think now that ... Milton Friedman’s project was always doomed to failure.

To repeat the key points of my argument:

On the intellectual side, the “neoclassical synthesis” — of which Friedman-style monetarism was essentially part, despite his occasional efforts to make it seem completely different — was inherently an awkward construct. Economists were urged to build everything from “micro foundations”... But to get a macro picture that looked anything like the real world, and which justified monetary activism, you needed to assume that for some reason wages and prices were slow to adjust.

Inevitably the drive for purism collided with the realistic accommodations, the ad hockery, needed to be useful; sure enough, half the macroeconomics profession basically said, “what are you going to believe, our models or your lying eyes?” and abandoned any good sense Friedman had originally brought to the subject.

On the political side, there was a similar collision. Right-wingers insisted — Friedman taught them to insist — that government intervention ... always made things worse. Monetarism added the clause, “except for monetary expansion to fight recessions.” Sooner or later gold bugs and Austrians, with their pure message, were going to write that escape clause out of the acceptable doctrine. So we have the most likely non-Trump GOP nominee calling for a gold standard, and the chairman of Ways and Means demanding that the Fed abandon its concerns about unemployment and focus only on controlling the never-materializing threat of inflation. ...

The point is that the monetarist idea no longer serves any useful purpose, intellectually or politically. ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Wednesday, April 13, 2016 at 08:14 AM

Permalink

Comments (15)

Lifespan inequality:

New study shows rich, poor have huge mortality gap in U.S., by Peter Dizikes; MIT News: Poverty in the U.S. is often associated with deprivation, in areas including housing, employment, and education. Now a study co-authored by two MIT researchers has shown, in unprecedented geographic detail, ... that in the U.S., the richest 1 percent of men lives 14.6 years longer on average than the poorest 1 percent of men, while among women in those wealth percentiles, the difference is 10.1 years on average.

This eye-opening gap is also growing rapidly: Over roughly the last 15 years, life expectancy increased by 2.34 years for men and 2.91 years for women who are among the top 5 percent of income earners in America, but by just 0.32 and 0.04 years for men and women in the bottom 5 percent of the income tables.

“When we think about income inequality in the United States, we think that low-income Americans can’t afford to purchase the same homes, live in the same neighborhoods, and buy the same goods and services as higher-income Americans,” says Michael Stepner, a PhD candidate in MIT’s Department of Economics. “But the fact that they can on average expect to have 10 or 15 fewer years of life really demonstrates the level of inequality we’ve had in the United States.”

Stepner and Sarah Abraham, another PhD candidate in MIT’s Department of Economics, are among the co-authors of a newly published paper summarizing the study’s findings, and have played central roles in a three-year research project establishing the results.

In addition to reporting the size and growth of the income gap, the study finds that the average lifespan varies considerably by region in the U.S. (by as much as 4.5 years), but that the sources of that regional variation are subtle, and, like the aggregate national gap, subject to further investigation.

“The patterns are not exactly what you might expect,” says Abraham, noting that regional variation in longevity does not seem strongly correlated with factors such as access to health care, environmental issues, income inequality, or the job market.

“We don’t find those to be as highly correlated with differences in longevity as we find measures of health behavior, such as smoking rates or obesity rates” [to be correlated with lifespan], Abraham observes.

The paper, “The Association between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014,” is being published ... by the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The authors are Raj Chetty, a professor of economics at Stanford University; Stepner and Abraham of MIT, who are the second and third authors on the paper; Shelby Lin, an analyst with McKinsey and Company in New York; Benjamin Scuderi, a predoctorate fellow in Harvard University’s Economics Department; Augustin Bergeron, a PhD candidate in Harvard University’s Economics Department; Nicholas Turner of the Office of Tax Analysis in the U.S. Department of the Treasury; and David Cutler, a professor of economics at Harvard University.

The geography of mortality

The researchers looked at 1.4 billion anonymized income tax filings from the federal government, and combined that with mortality data from the years 2001 through 2014 from the Social Security Administration. This represents the most complete geographic and demographic landscape of mortality in America.

Among other things, the growth of the gap in mortality rates — by nearly three years — struck the researchers as noteworthy. To put it in perspective, they note that federal health officials estimate that curing all forms of cancer would add three years to the average lifespan.

“That change over the last 15 years is the equivalent of the richest Americans winning the war on cancer,” Stepner observes.

At the same time, the researchers are quick to point out that the findings cannot immediately be reduced to simple cause-and-effect explanations. For instance, as social scientists have long observed, it is very hard to say whether having wealth leads to better health — or if health, on aggregate, is a prerequisite for accumulating wealth. Most likely, the two interact in complex ways, something the study cannot resolve.

“It’s a descriptive story,” Stepner says of the data.

A new puzzle emerging from the study, the authors note, is that differences in lifespan exist along the entire continuum of wealth in the U.S.; it is not as if, say, the top 10 percent of earners cluster around identical average lifespans.

“As you go up in the income distribution, life expectancy continues to increase, at every point,” Stepner says.

And then there are the new geographic patterns in the findings. For instance: Eight of the 10 states with the lowest life expectancies for people in the bottom income quartile form a contiguous belt, curving around from Michigan through Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Kansas.

So while average lifespans for everyone are lower in some Southern states, the poor do not fare worse in those places than they do in other regions.

“The Deep South is the lowest-income area in America, but when we’re looking at life expectancy conditional on having a low income, it’s not worse to be poor in the Deep South than it is in other areas of America,” Stepner says. “It’s just that there are far more poor people living in the South.”

Future research: Think local

The researchers say that more analysis on the sources of local variation in lifespans could be among the most fruitful research areas stemming from the current paper. The research team is releasing all the data from the study today as well.

Among the municipalities where low-income people have experienced the greatest increases in lifespan from 2001-2014, for example, are Toms River, New Jersey; Birmingham, Alabama; and Richmond, Virginia. Cities with the largest drops in lifespan among the poor are Tampa and Pensacola, Florida; and Knoxville, Tennessee.

“We’re not making any normative statements about what policy should be, but there is a wide dispersion of [results] happening in the U.S.,” Abraham says. “That might need to be addressed at a more granular level.”

Places with the overall longest lifespans for the poor include New York City, with a chart-topping 81.8 years on average, as well as a passel of cities in California. The bottom of that list includes Gary, Indiana (77.4 years on average); Las Vegas; and Oklahoma City.

Among the top income earners, people live longest in Salt Lake City (87.8 years on average); Portland, Maine; and Spokane, Washington. The rich have the shortest lives in Las Vegas (84.1 years on average); Gary, Indiana; and Honolulu.

Abraham also observes that the findings could have implications for national policy programs, as well.

“Things like Social Security aren’t going to be as redistributive if the richer people are getting paid for 10 more years than the poorer people,” she says.

Overall, the researchers say they hope to spark a larger discussion among the research and policy communities.

“We don’t have all the answers,” Abraham says. “But it’s really important to make these statistics widely used so people have an idea of what the magnitude of these problems is, where they might focus their attention, and why this matters.”

Posted by Mark Thoma on Wednesday, April 13, 2016 at 07:14 AM in Economics |

Permalink

Comments (14)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Wednesday, April 13, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (203)

Chris Dillow:

For an inheritance tax: The news that David Cameron got £500,000 tax-free from his parents raises the question of how or whether inheritances should be taxed. My view is that they should be, and heavily so.

Certainly, a lot of the defences of inheritance look pathetically weak. For example:

“Because a parent’s income was taxed, taxing inheritances is a form of double taxation.” But the same is true for most incomes. When people buy the Investors Chronicle – thus handing money over to me - they do so out of taxed income. Should I therefore escape income tax?

“People should be able to provide for their kids.” Most recipients of inheritances, however, are middle-aged. And the prospect of a big inheritance can actually damage offspring, by reducing their self-reliance and incentives to work and save. ...

“Inheritance tax punishes aspiration.” In most cases, though, the aspiration is an illusory one. HMRC data show that of the 279,301 estates that were left in 2012-13, a mere 6.4% attracted tax. Even if the IHT threshold were greatly reduced, only a minority would pay it.

This, though, brings me to why I favour inheritance taxes. ... We should think of every penny of inheritance which is not taxed as a penny which has to be raised from income taxes. Low inheritance tax thus means high income tax. From this perspective, those who want tax-free inheritances are exactly like benefit scroungers. They want something for nothing at the expense of hardworking tax-payers. It is, therefore, the lack of a serious inheritance tax – and thus the higher taxes on workers, savers and entrepreneurs – that is truly an attack upon aspirations.

If – as I find plausible – the prospect of getting an inheritance reduces labour supply, then optimal taxation might require big inheritance tax rates; these might be less distortionary than income taxes. ...

Surely, there is something fundamentally unjust about being able to get £500,000 tax-free from not working, when the same sum obtained by work would be heavily taxed.

I suspect opposition to sensible inheritance taxes owes more to the rich’s colossal sense of entitlement than it does to justice or economic efficiency. ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Tuesday, April 12, 2016 at 07:08 AM in Economics, Taxes |

Permalink

Comments (160)

Maurice Obstfeld on the latest World Economic Outlook from the IMF:

Global Growth: Too Slow for Too Long: Global growth continues, but at an increasingly disappointing pace that leaves the world economy more exposed to negative risks. Growth has been too slow for too long.

The new World Economic Outlook released today anticipates a slight acceleration in growth this year, from 3.1 to 3.2 percent, followed by 3.5 percent growth in 2017. Our projections, however, continue to be progressively less optimistic over time.

The downgraded forecasts reflect a broad-based slowdown across all countries. ...

Both to support global growth and to guard against downside risks to that baseline scenario, we propose a three-pronged policy approach based on monetary, fiscal and structural policies. ...

With its downside possibilities, the current diminished outlook calls for an immediate, proactive response. To repeat: there is no longer much room for error. But by clearly recognizing the risks they jointly face and acting together to prepare for them, national policymakers can bolster confidence, support growth, and guard more effectively against the risk of a derailed recovery.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Tuesday, April 12, 2016 at 06:52 AM in Economics |

Permalink

Comments (36)

At MoneyWatch:

Donald Trump's fuzzy deficit-cutting math, by Mark A. Thoma: Donald Trump has big -- huuuge -- plans for the economy. Do those plans have any merit?

Perhaps it's a mistake to take presidential candidates' economic proposals as serious policy rather than signals of tribal affiliation, opening bids in post-election negotiations or pandering for votes by telling various groups what they want to hear, even if the parts don't add up to a feasible whole.

Nevertheless, I'm taking Trump's proposals for taxes, the government debt, Medicare and Social Security as though they are genuine...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Tuesday, April 12, 2016 at 06:24 AM in Economics, Politics |

Permalink

Comments (13)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Tuesday, April 12, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (136)

Helicopter Milton:

What tools does the Fed have left? Part 3: Helicopter money:

“Let us suppose now that one day a helicopter flies over this community and drops an additional $1,000 in bills from the sky, which is, of course, hastily collected by members of the community. Let us suppose further that everyone is convinced that this is a unique event which will never be repeated." (Milton Friedman, “The Optimum Quantity of Money,” 1969)

"The deflation speech saddled me with the nickname 'Helicopter Ben.' In a discussion of hypothetical possibilities for combating deflation I mentioned an extreme tactic—a broad-based tax cut combined with money creation by the central bank to finance the cut. Milton Friedman had dubbed the approach a 'helicopter drop' of money. Dave Skidmore, the media relations officer…had advised me to delete the helicopter-drop metaphor…'It’s just not the sort of thing a central banker says,' he told me. I replied, 'Everybody knows Milton Friedman said it.' As it turned out, many Wall Street bond traders had apparently not delved deeply into Milton’s oeuvre.” (Ben Bernanke, The Courage to Act, 2015, p. 64)

In previous posts, I discussed tools that the Fed might use in response to a future slowdown in the U.S. economy. I argued that, even if the scope for conventional interest-rate cuts is limited by already-low rates, the Fed has additional policy tools available, ranging from forward guidance about future rate policies to additional quantitative easing to targeting longer-term rates. Still, so long as people have the option of holding currency, there are limits to how far the Fed or any central bank can depress interest rates.[1] Moreover, the benefits of low rates may erode over time, while the costs are likely to increase. Consequently, at some point monetary policy faces diminishing returns.

When monetary policy alone is inadequate to support economic recovery or to avoid too-low inflation, fiscal policy provides a potentially powerful alternative—especially when interest rates are “stuck” near zero [2] However, in recent years, legislatures in advanced industrial economies have for the most part been reluctant to use fiscal tools, in many cases because of concerns that government debt is already too high. In this context, Milton Friedman’s idea of money-financed (as opposed to debt-financed) tax cuts—“helicopter money”—has received a flurry of attention, with influential advocates including Adair Turner, Willem Buiter, and Jordi Gali.

In this post, I consider the merits of helicopter money as a (presumably last-resort) strategy for policymakers. I make two points. First, in theory at least, helicopter money could prove a valuable tool. In particular, it has the attractive feature that it should work even when more conventional monetary policies are ineffective and the initial level of government debt is high. However, second, as a practical matter, the use of helicopter money would involve some difficult issues of implementation. These include (1) the need to integrate the approach with standard monetary policy frameworks and (2) the challenge of achieving the necessary coordination between fiscal and monetary policymakers, without compromising central bank independence or long-run fiscal discipline. I propose some tentative solutions for these problems.

To be clear, the probability of so-called helicopter money being used in the United States in the foreseeable future seems extremely low. ... However, under certain extreme circumstances—sharply deficient aggregate demand, exhausted monetary policy, and unwillingness of the legislature to use debt-financed fiscal policies—such programs may be the best available alternative. It would be premature to rule them out.

[There is quite a bit more detail in the full post.]

Posted by Mark Thoma on Monday, April 11, 2016 at 07:37 AM

Permalink

Comments (52)

Larry Summers:

What’s behind the revolt against global integration?: Since the end of World War II, a broad consensus in support of global economic integration as a force for peace and prosperity has been a pillar of the international order. ...

This broad program of global integration has been more successful than could reasonably have been hoped. ... Yet a revolt against global integration is underway in the West. ...

One substantial part of what is behind the resistance is a lack of knowledge. ...The core of the revolt against global integration, though, is not ignorance. It is a sense — unfortunately not wholly unwarranted — that it is a project being carried out by elites for elites, with little consideration for the interests of ordinary people. ...

Elites can continue on the current path of pursuing integration projects and defending existing integration, hoping to win enough popular support that their efforts are not thwarted. On the evidence of the U.S. presidential campaign and the Brexit debate, this strategy may have run its course. ...

Much more promising is this idea: The promotion of global integration can become a bottom-up rather than a top-down project. The emphasis can shift from promoting integration to managing its consequences. This would mean a shift from international trade agreements to international harmonization agreements, whereby issues such as labor rights and environmental protection would be central, while issues related to empowering foreign producers would be secondary. It would also mean devoting as much political capital to the trillions of dollars that escape taxation or evade regulation through cross-border capital flows as we now devote to trade agreements. And it would mean an emphasis on the challenges of middle-class parents everywhere who doubt, but still hope desperately, that their kids can have better lives than they did.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Monday, April 11, 2016 at 07:02 AM in Economics, International Trade |

Permalink

Comments (61)

Systemically important presidential elections:

Snoopy the Destroyer, by Paul Krugman, NY Times: Has Snoopy just doomed us to another severe financial crisis? Unfortunately, that’s a real possibility, thanks to a bad judicial ruling that threatens a key part of financial reform. ...

At the end of 2014 the regulators designated MetLife, whose business extends far beyond individual life insurance, a systemically important financial institution. Other firms faced with this designation have tried to get out by changing their business models. For example, General Electric ... sold off much of its finance business. But MetLife went to court. And it has won a favorable ruling from Rosemary Collyer, a Federal District Court judge.

It was a peculiar ruling. Judge Collyer repeatedly complained that the regulators had failed to do a cost-benefit analysis, which the law doesn’t say they should do, and for good reason. Financial crises are, after all, rare but drastic events; it’s unreasonable to expect regulators to game out in advance just how likely the next crisis is, or how it might play out, before imposing prudential standards. To demand that officials quantify the unquantifiable would, in effect, establish a strong presumption against any kind of protective measures.

Of course, that’s what financial firms want. Conservatives like to pretend that the “systemically important” designation is actually a privilege, a guarantee that firms will be bailed out. Back in 2012 Mitt Romney described this part of reform as “a kiss that’s been given to New York banks”..., an “enormous boon for them.” Strange to say, however, firms are doing all they can to dodge this “boon” — and MetLife’s stock rose sharply when the ruling came down.

The federal government will appeal..., but even if it wins the ruling may open the floodgates to a wave of challenges to financial reform. And that’s the sense in which Snoopy may be setting us up for future disaster.

It doesn’t have to happen. As with so much else, this year’s election is crucial. A Democrat in the White House would enforce the spirit as well as the letter of reform — and would also appoint judges sympathetic to that endeavor. A Republican, any Republican, would make every effort to undermine reform, even if he didn’t manage an explicit repeal.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying that the 2010 financial reform was enough. The next crisis might come even if it remains intact. But the odds of crisis will be a lot higher if it falls apart.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Monday, April 11, 2016 at 06:29 AM in Economics, Financial System, Regulation |

Permalink

Comments (40)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Monday, April 11, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (106)

Simon Wren-Lewis:

Can central banks make 3 major mistakes in a row and stay independent?: Mistake 1 If you are going to blame anyone for not seeing the financial crisis coming, it would have to be central banks. They had the data that showed a massive increase in financial sector leverage. That should have rung alarm bells...

Mistake 2 Of course the main culprit for the slow recovery from the Great Recession was austerity... But the slow recovery also reflects a failure of monetary policy. In my view the biggest failure occurred very early on in the recession. Monetary policy makers should have said very clearly, both to politicians and to the public, that with interest rates at their lower bound they could no longer do their job effectively, and that fiscal stimulus would have helped them do that job. Central banks might have had the power to prevent austerity happening, but they failed to use it. ...

What could be mistake 3 The third big mistake may be being made right now in the UK and US. It could be called supply side pessimism. Central bankers want to ‘normalise’ their situation... They want to declare that they are back in control. But this involves writing off the capacity that appears to have been lost as a result of the Great Recession.

The UK and US situations are different. ...

I think these differences are details. In both cases the central bank is treating potential output as something that is independent of its own decisions and the level of actual output. ...

Perhaps that is correct, but there has to be a fair chance that it is not. If it is not, by trying to adjust demand to this incorrectly perceived low level of supply central banks are wasting a huge amount of potential resources. Their excuses for doing this are not strong. It is not as if our models of aggregate supply and inflation are well developed and reliable... The real question to ask is whether firms with current technology would like to produce more if the demand for this output was there, and we do not have good data on that.

What central banks should be doing in these circumstances is allowing their economies to run hot for a time, even though this might produce some increase in inflation above target. If when that is done both price and wage inflation appear to be continuing to rise above target, while ‘supply’ shows no sign of increasing with demand, then pessimism will have been proved right and the central bank can easily pull things back. The costs of this experiment will not have been great...

It does not appear that the Bank of England or Fed are prepared to do that. If we subsequently find out that their supply side pessimism was incorrect ..., this could spell the end of central bank independence. ... The Great Moderation is becoming a distant memory clouded by more recent failures. ... Mainstream economics remains pretty committed to central bank independence. But as we have seen with austerity, at the end of the day what mainstream economics thinks is not decisive when it comes to political decisions on economic matters. ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Sunday, April 10, 2016 at 09:14 AM in Economics, Monetary Policy, Politics |

Permalink

Comments (44)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Sunday, April 10, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (117)

Brad Delong:

A Note on the Likelihood of Recession: With global inflation currently more than quiescent, there is no chance that global recovery will be—as Rudi Dornbusch used to say—assassinated by inflation-fighting central banks raising interest rates.

As for recovery being assassinated by financial chaos, we face a paradox here: Financial risks that policymakers and economists can see are those that bankers can see and hedge against as well. It is only the financial risks that policymakers and economists do not see that are truly dangerous. Many back in 2005 saw the global imbalance of China's export surplus and feared disaster from a fall in the dollar coupled with the discovery of money-center institutions having sold massive amounts of unhedged dollar puts. Very few, if any--even among those who believed US housing was a massive bubble likely to pop—feared that any problems created thereby would not be rapidly handled and neutralized by the Federal Reserve.

The most likely danger of recession is thus absent, and the second most likely danger is unknowable.

That leaves the third: a global economy that drifts into a downturn because both fiscal and monetary policymakers sit on their hands and refuse to use the stimulative demand management tools they have.

Here there is, I think, some reason to fear. A passage from a recent speech by the nearly-godlike Stan Fischer was flagged to me by Tim Duy:

If the recent financial market developments lead to a sustained tightening of financial conditions, they could signal a slowing in the global economy that could affect growth and inflation in the United States. But we have seen similar periods of volatility in recent years--including in the second half of 2011--that have left little visible imprint on the economy, and it is still early to judge the ramifications of the increased market volatility of the first seven weeks of 2016. As Chair Yellen said in her testimony to the Congress two weeks ago, while "global financial developments could produce a slowing in the economy, I think we want to be careful not to jump to a premature conclusion about what is in store for the U.S. economy”…

And Tim commented:

This… again misses the Fed's response to financial turmoil…. I really do not understand how Fed officials can continue to dismiss market turmoil using comparisons to past episodes when those episodes triggered a monetary policy response. They don't quite seem to understand the endogeneity in the system…

However, anything that could be called a “global recession” in the near term still looks like a less than 20% chance to me. But that is up from a 5% chance nine months ago. ...

A Note on China: ...

A Note on the Non-Need for a New Plaza Accord: ...

A Note on Negative Interest Rates: ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Saturday, April 9, 2016 at 02:06 PM in Economics |

Permalink

Comments (45)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Saturday, April 9, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (211)

Next paper at the conference:

Inequality and Aggregate Demand, by with Adrien Auclert and Mathew Rognile: Abstract: We explore the quantitative effects of transitory and persistent increases in income inequality on equilibrium interest rates and output. Our starting point is a Bewley-Huggett-Aiyagari model featuring rich heterogeneity and earnings dynamics as well as downward nominal wage rigidities. A temporary rise in inequality, if not accommodated by monetary policy, has an immediate effect on output that can be quantified using the empirical covariance between income and marginal propensities to consume. A permanent rise in inequality can lead to a permanent Keynesian recession, which is not fully offset by monetary policy due to a lower bound on interest rates. We show that the magnitude of the real interest rate fall and the severity of the steady-state slump can be approximated by simple formulas involving quantifiable elasticities and shares, together with two parameters that summarize the effect of idiosyncratic uncertainty and real interest rates on aggregate savings. For plausible parametrizations the rise in inequality can push the economy into a liquidity trap and create a deep recession. Capital investment and deficit-financed fiscal policy mitigate the fall in real interest rates and the severity of the slump.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Friday, April 8, 2016 at 10:34 AM in Economics, Income Distribution |

Permalink

Comments (18)

Barry Eichengreen (I left out quite a bit of the discussion...):

The Case for a Grand Bargain: The current malaise of stagnation and lowflation is a global phenomenon. And, unfortunately, individual efforts to defeat it, by central banks and governments proceeding on their own, are clearly not working. ... Nor do policy makers in different countries all share a common diagnosis of the nature of the problem and its remedy. ...

But in the underbrush of these disagreements lie the seeds of a grand bargain. Countries with fiscal room for maneuver, such as the United States and Germany, should agree to use it. Economies lacking fiscal space for their part can agree to use monetary stimulus more aggressively... And countries where structural reform is urgent, not just the Southern European countries that are Germany’s concern but also emerging markets like China and Brazil, can recommit to the reform...

This is not the perfect bargain, but then we do not live in a perfect world. In particular, the dollar would strengthen against other currencies... That strong dollar would cause U.S. exporters to howl, but that is the price of international cooperation to jumpstart global growth. A relatively strong dollar is appropriate, after all, given the relatively strong condition of the U.S. economy... A further problem or cost is that global imbalances – a growing external deficit for the U.S. and surpluses for other countries – would reemerge.

But only temporarily. Once global growth firmed, U.S. fiscal stimulus could be withdrawn. Monetary policies in other countries could be normalized. The dollar would give back ground, and global imbalances would narrow. ...

Skeptics will say that I am a dreamer for imagining this grand bargain. But the alternative to this dream is an ongoing economic nightmare.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Friday, April 8, 2016 at 07:33 AM in Economics |

Permalink

Comments (29)

Paul Krugman:

Sanders Over the Edge, by Paul Krugman, Commentary, NY Times: From the beginning, many and probably most liberal policy wonks were skeptical about Bernie Sanders. On many major issues — including the signature issues of his campaign, especially financial reform — he seemed to go for easy slogans over hard thinking. And his political theory of change, his waving away of limits, seemed utterly unrealistic.

Some Sanders supporters responded angrily when these concerns were raised... But intolerance and cultishness from some of a candidate’s supporters are one thing; what about the candidate himself? Unfortunately,... Mr. Sanders is starting to sound like his worst followers. Bernie is becoming a Bernie Bro.

Let me illustrate the point about issues by talking about bank reform..., were big banks really at the heart of the financial crisis...?

Many analysts concluded years ago that the answers to both questions were no. Predatory lending was largely carried out by smaller, non-Wall Street institutions like Countrywide Financial; the crisis itself was centered not on big banks but on “shadow banks” like Lehman Brothers that weren’t necessarily that big..., pounding the table about big banks misses the point. ...

And this absence of substance beyond the slogans seems to be true of his positions across the board.

You could argue that policy details are unimportant as long as a politician has the right values and character ... But ... the way Mr. Sanders is now campaigning raises serious character and values issues.

It’s one thing for the Sanders campaign to point to Hillary Clinton’s Wall Street connections, which are real, although the question should be whether they have distorted her positions, a case the campaign has never even tried to make. But recent attacks on Mrs. Clinton as a tool of the fossil fuel industry are just plain dishonest, and speak of a campaign that has lost its ethical moorings.

And then there was Wednesday’s rant about how Mrs. Clinton is not “qualified” to be president. ...

Is Mr. Sanders positioning himself to join the “Bernie or bust” crowd, walking away if he can’t pull off an extraordinary upset, and possibly helping put Donald Trump or Ted Cruz in the White House? If not, what does he think he’s doing?

The Sanders campaign has brought out a lot of idealism and energy that the progressive movement needs. It has also, however, brought out a streak of petulant self-righteousness among some supporters. Has it brought out that streak in the candidate, too?

Posted by Mark Thoma on Friday, April 8, 2016 at 06:07 AM in Economics, Politics |

Permalink

Comments (271)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Friday, April 8, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (116)

Tim Duy:

How Much of an Overshoot?: The Federal Reserve formally adopted a 2 percent inflation target back in January of 2012.

Policymakers at the central bank amended their objective this year to clarify that they expect "symmetric errors" around the target; in other words there is the possibility of the central bank overshooting or undershooting its self-proclaimed goal on inflation. Despite this clarification, concerns about the Fed’s commitment to the target persist and have intensified following Fed Chair Janet Yellen's speech last month. Even before then, however, it was easy to see why such worries existed. The central bank began the process of policy “normalization,” first by ending quantitative easing and then by raising benchmark interest rates, even though inflation has fallen short of the Fed's self-proclaimed target every month since May of 2012.

This raises a simple question: Given consistently below-target inflation since the Fed adopted its target, how much, if any, overshooting might the Fed be willing to tolerate as the expansion continues? ... Continued at Bloomberg

Posted by Mark Thoma on Thursday, April 7, 2016 at 09:17 AM in Economics, Monetary Policy |

Permalink

Comments (11)

I am here today and tomorrow:

St. Louis Advances in Research (STLAR) Conference Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Thursday, April 7, 2016

11:30 – 12:30 pm Consumption and House Prices in the Great Recession: Model meets Evidence Presenter: Greg Kaplan (Princeton University) Coauthors: Kurt Mitman, Gianluca Violante

1:30 – 2:30 pm How Credit Constraints Impact Job Finding Rates, Sorting & Aggregate Output Presenter: Kyle Herkenhoff (University of Minnesota) Coauthors: Ethan Cohen-Cole, Gordon Phillips

2:45 – 3:45 pm The Influence of Benefit Extensions on Unemployment Presenter: Loukas Karabarbounis (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis)

4:00 – 5:00 pm House Prices and Consumer Spending Presenter: David Berger (Northwestern University) Coauthors: Veronica Guerreri, Guido Lorenzoni, Joe Vavra

5:00 – 6:00 pm Do Banks Pass Through Credit Expansions to Consumers Who Want to Borrow? Presenter: Johannes Stroebel (New York University) Coauthors: Sumit Agarwal, Souphala Chomsisengphet, Neale Mahoney

Friday, April 8, 2016

9:00 – 10:00 am Lack of Selection and Limits to Delegation: Firm Dynamics in Developing Countries Presenter: Ufuk Akcigit (University of Chicago) Coauthors: Harun Alp, Michael Peters

10:00 – 11:00 am Urban-Rural Wage Gaps in Developing Countries: Spatial Misallocation or Efficient Sorting? Presenter: David Lagakos (University of California, San Diego) Coauthors: Mushfiq Mobarak, Michael Waugh

11:15 – 12:15 pm Inequality and Aggregate Demand Presenter: Adrien Auclert (Stanford University)

12:15 – 1:15 pm Unconventional Monetary Policy and the Allocation of Credit Presenter: Amir Kermani (Berkeley University) Coauthors: Marco Di Maggio, Christopher Palmer

Posted by Mark Thoma on Thursday, April 7, 2016 at 09:16 AM in Conferences, Economics |

Permalink

Comments (0)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Thursday, April 7, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (221)

Tim Duy:

Dovish Minutes, by Tim Duy: The FOMC minutes indicates the Fed is just a dovish as believed. This was somewhat surprising given the tendency of minutes to have a more balanced perspective which would appear to be hawkish relative to current market expectations. But not this time. This time the message was fairly clear: They can't ignore the asymmetry of policy risks any longer. Gradual went to glacial, with April now off the table, leaving June as the next possible data for a rate hike. Expect Fedspeak to sound somewhat hawkish given they will want to keep June on the table - but I am less than certain they will have the data in hand to justify another hike until the second half of the year.

Meeting participants were generally confident in the outlook:

With respect to the outlook for economic activity and the labor market, participants shared the assessment that, with gradual adjustments in the stance of monetary policy, real GDP would continue to increase at a moderate rate over the medium term and labor market indicators would continue to strengthen. Participants observed that strong job gains in recent months had reduced concerns about a possible slowing of progress in the labor market.

But outside of the consumer, all is not rosy:

Many participants, however, anticipated that relative strength in household spending would be partially offset by weakness in net exports associated with lackluster foreign growth and the appreciation of the dollar since mid-2014. In addition, business fixed investment seemed likely to remain sluggish.

And global concerns loomed large:

Furthermore, participants generally saw global economic and financial developments as continuing to pose risks to the outlook for economic activity and the labor market in the United States. In particular, several participants expressed the view that the underlying factors abroad that led to a sharp, though temporary, deterioration in global financial conditions earlier this year had not been fully resolved and thus posed ongoing downside risks.

Caveats abound, however:

Several participants also noted the possibility that economic activity or labor market conditions could turn out to be stronger than anticipated. For example, strong expansion of household demand could result in rapid employment growth and overly tight resource utilization, particularly if productivity gains remained sluggish.

Is the economy at full employment? Maybe:

Some participants judged that current labor market conditions were at or near those consistent with maximum sustainable employment, noting that the unemployment rate was at or below their estimates of its longer-run normal level and citing anecdotal reports of labor shortages or increased wage pressures.

Maybe not:

In contrast, some other participants judged that the economy had not yet reached maximum employment. They noted several indicators other than the unemployment rate that pointed to remaining underutilization of labor resources; these indicators included the still-high rate of involuntary part-time employment and the low level of the employment-to-population ratio for prime-age workers. The surprisingly limited extent to which aggregate data indicated upward pressure on wage growth also suggested some remaining slack in labor markets.

The climb in the unemployment rate since the March meeting supports the latter over the former. There was mixed views regarding the inflation outlook:

Participants commented on the recent increase in inflation. Some participants saw the increase as consistent with a firming trend in inflation. Some others, however, expressed the view that the increase was unlikely to be sustained, in part because it appeared to reflect, to an appreciable degree, increases in prices that had been relatively volatile in the past.

But concerns about too low inflation clear dominated:

Several participants indicated that the persistence of global disinflationary pressures or the possibility that inflation expectations were moving lower continued to pose downside risks to the inflation outlook. A few others expressed the view that there were also risks that could lead to inflation running higher than anticipated; for example, overly tight resource utilization could push inflation above the Committee's 2 percent goal, particularly if productivity gains remained sluggish.

And there was concern that low inflation was bleeding into expectations:

Some participants concluded that longer-run inflation expectations remained reasonably stable, but some others expressed concern that longer-run inflation expectations may have already moved lower, or that they might do so if inflation was to persist for much longer at a rate below the Committee's objective.

Notably, no one was concerned that inflation expectations were trending up. The consensus was stable or deteriorating. One-sided risks.

The primary reason the Fed anticipates stable growth this year is because they marked down interest rate forecasts:

...most participants, while recognizing the likely positive effects of recent policy actions abroad, saw foreign economic growth as likely to run at a somewhat slower pace than previously expected, a development that probably would further restrain growth in U.S. exports and tend to damp overall aggregate demand. Several participants also cited wider credit spreads as a factor that was likely to restrain growth in demand. Accordingly, many participants expressed the view that a somewhat lower path for the federal funds rate than they had projected in December now seemed most likely to be appropriate for achieving the Committee's dual mandate. Many participants also noted that a somewhat lower projected interest rate path was one reason for the relatively small revisions in their medium-term projections for economic activity, unemployment, and inflation.

Altogether, the risks are simply too one-sided to ignore:

Several participants also argued for proceeding cautiously in reducing policy accommodation because they saw the risks to the U.S. economy stemming from developments abroad as tilted to the downside or because they were concerned that longer-term inflation expectations might be slipping lower, skewing the risks to the outlook for inflation to the downside. Many participants noted that, with the target range for the federal funds rate only slightly above zero, the FOMC continued to have little room to ease monetary policy through conventional means if economic activity or inflation turned out to be materially weaker than anticipated, but could raise rates quickly if the economy appeared to be overheating or if inflation was to increase significantly more rapidly than anticipated. In their view, this asymmetry made it prudent to wait for additional information regarding the underlying strength of economic activity and prospects for inflation before taking another step to reduce policy accommodation.

The winter turmoil made the asymmetric risks all-too-real. They need to allow the economy to run hot to justify sufficient rate hikes to drive a wedge between policy and the zero bound. They need to make a choice: Risk inflation, or risk returning to the zero bound? They are coming around to seeing the former as a less costly risk as the latter.

This begs the question of how quick they will be to react to inflation that overshoots 2%. I don't think they will react too quickly - they will need to tolerate some overshooting to avoid cutting the recovery off at the knees. It will still be about the balance of risks until interest rates are much higher.

Finally, the pretty much decided they wouldn't have enough data to hike rates in April:

A number of participants judged that the headwinds restraining growth and holding down the neutral rate of interest were likely to subside only slowly. In light of this expectation and their assessment of the risks to the economic outlook, several expressed the view that a cautious approach to raising rates would be prudent or noted their concern that raising the target range as soon as April would signal a sense of urgency they did not think appropriate. In contrast, some other participants indicated that an increase in the target range at the Committee's next meeting might well be warranted if the incoming economic data remained consistent with their expectations for moderate growth in output, further strengthening of the labor market, and inflation rising to 2 percent over the medium term.

Not clear that they will in June either. First quarter growth numbers are looking weak, so they may want a clear picture of the second quarter before acting. That speaks to July or September.

Bottom Line: The Fed is on hold until they are sufficiently confident they can make a liftoff stick. The bar is higher now given the focus on asymmetric risks. They won't want to take June off the table just yet, so expect them to say that it is still too early to rule it out. April, however, is set to be a yawner.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Wednesday, April 6, 2016 at 03:13 PM in Economics, Fed Watch, Monetary Policy |

Permalink

Comments (11)

David Beckworth:

The Safe Asset Problem is Back: Negative Interest Rate Edition: The safe asset shortage problem is back. Actually, it never went away..., yields on government bonds considered safe assets have been steadily declining since the crisis broke out.

This problem is now manifesting itself in a new form: central banks tinkering with negative interest rates. Many view this development as the latest manifestation of central banks running amok. A more nuance read is that central banks are continuing to imperfectly respond to safe asset shortage problem. ...

But many observers miss this point. They confuse the symptom--central bankers tinkering with negative interest rates--for the cause--the safe asset shortage. So I want to revisit the safe asset shortage problem in this post by reviewing what exactly it is, why it has persisted for so long, and what can be done to remedy it. ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Wednesday, April 6, 2016 at 10:33 AM in Economics, Monetary Policy |

Permalink

Comments (29)

“Networks and the Macroeconomy: An Empirical Exploration,” by Daron Acemoglu, Ufuk Akcigit, and William Kerr (this will be published in the NBER Macroeconomics Annual):

How Network Effects Hurt Economies, by Peter Dizikes, MIT News Office: When large-scale economic struggles hit a region, a country, or even a continent, the explanations tend to be big in nature as well.

Macroeconomists — who study large economic phenomena — often look for sweeping explanations of what has gone wrong, such as declines in productivity, consumer demand, or investor confidence, or significant changes in monetary policy.

But what if large-scale economic slumps can be traced to declines in relatively narrow industrial sectors? A newly published study co-authored by an MIT economist provides evidence that economic problems may often have smaller points of origin and then spread as part of a network effect.

“Relatively small shocks can become magnified and then become shocks you have to contend with [on a large scale],” says MIT economist Daron Acemoglu, one of the authors of a paper detailing the research.

The findings run counter to “real business cycle theory,” which became popular in the 1970s and holds that smaller, industry-specific effects tend to get swamped by larger, economy-wide trends.

More precisely, Acemoglu and his colleagues have found cases where industry-specific problems lead to six-fold declines in production across the U.S. economy as a whole. For example, for every dollar of value-added growth lost in the manufacturing industries because of competition from China, six dollars of value-added growth were lost in the U.S. economy as a whole.

The researchers also examined four different types of economic shocks to the U.S. economy that occurred over the years 1991-2009, and quantified the extent to which those problems spread “upstream” or “downstream” of the central industry in question — that is, whether the network effects more strongly hurt industrial suppliers or businesses that sell products and provide services to consumers.

All told, the researchers state in the paper, “Our results suggest that the transmission of various different types of shocks through economic networks and industry interlinkages could have first-order implications for the macroeconomy.” ...

Upstream or downstream

Acemoglu, Afcigit, and Kerr used manufacturing data from the National Bureau of Economic Analysis, and industry-specific data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, to examine four economic shocks hitting the U.S. economy during that 1991-2009 period. Those were: the impact of export competition on U.S. manufacturing; changes in federal government spending, which affect areas such as defense manufacturing; changes in Total Factor Productivity; and variation in levels of patents coming from foreign industry.

As noted, the network effect of manufacturing competition with China made the overall economic shock about six times as great as it was to manufacturing alone. (This research built on previously published work by economists David Autor of MIT, David Dorn of the University of Zurich, and Gordon Hanson of the University of California at San Diego, sometimes in collaboration with Acemoglu and MIT graduate student Brendan Price.)

In studying changes in the levels of federal spending after 1992, the researchers found a network effect about three to five times as large as that on directly-affected firms alone.

The decline in Total Factor Productivity constituted a smaller economic shock but one with a larger network effect, of more than 15 times the initial impact. In the case of increased foreign patenting (another way of looking at corporate productivity), the researchers found a network effect similar to that of Total Factor Productivity.

The first two of these areas constitute demand-side shocks, affecting consumer demand for the products in question. The last two are supply-side shocks, affecting firms’ ability to be good at what they do.

One of the key findings of the study, which confirms and builds on existing theory, is that demand-side shocks spread almost exclusively “upstream” in economic networks, and supply-side shocks spread almost exclusively “downstream.” To see why, Acemoglu suggests, consider an auto manufacturer, which has parts suppliers upstream and is linked with auto dealers, repair shops, and other businesses downstream.

When auto demand drops, “It’s the suppliers [upstream] that get affected,” Acemoglu explains. “You’re going to cut the production of autos, and you buy less of each of the inputs,” or supplies.

Now suppose the supply changes, perhaps due to an increase in manufacturing efficiency, which makes cars cheaper. In that case, Acemoglu adds, “People who use auto as inputs will buy more of them” — picture a delivery company — “so that shock will get transmitted to the downstream industries.”

To be sure, it is widely understood that the auto industry, like almost every other industry, is situated within a larger economic network. Yet estimating the spillover effects of struggles within any given industry, in the quantitative form of the current study, is rarely done.

“Given the importance of this, it’s surprising how scant the evidence is,” Acemoglu says. ...

This could have policy implications: Proponents of government investment, such as the so-called stimulus bill of 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, have contended that government spending creates a “multiplier effect” in terms of growth. Opponents of such legislation sometimes assert that government spending crowds out private investment and thus does not generate more growth than would otherwise occur. In theory, a more granular understanding of these network effects could help describe and define what a multiplier effect is, and in which industrial areas it may be the most pronounced. ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Wednesday, April 6, 2016 at 12:24 AM in Economics, Macroeconomics |

Permalink

Comments (25)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Wednesday, April 6, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (251)

Tim Duy:

Fed Has Little Reason to Hike Rates, by Tim Duy: Despite some occasionally hawkish rhetoric from a handful of disaffected Federal Reserve bank presidents, expect the Fed to remain on hold until inflationary threats clearly emerge. In practice, that means the Fed is not likely to raise rates until the unemployment rate resumes its downward trajectory. Soft though generally positive data coupled with market turbulence over the winter scared most policymakers straight with regards to their overly-optimistic plans to normalize policy. The risks to the outlook are simply too one-sided too believe this is anything like the tightening cycles of the past.

Generally positive incoming data continues to defy the predictions of the recessionistas. ISM data, both manufacturing:

and nonmanufacturing:

posted improved headline numbers with general solid internals. The worst of the manufacturing downturn may be behind us. The JOLTS numbers:

have remained fairly stable in recent months, suggesting no significant changes in dynamics in labor flows in and out of firms. Not surprisingly, nonfarm payroll growth remains on its steady path:

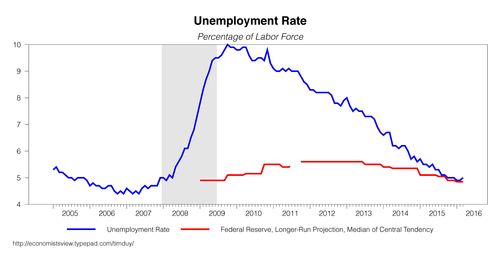

The unemployment rate ticked up in March as the labor force grew:

The Fed would like unemployment to settle somewhat below their estimates of the natural rate to promote further reduction of underemployment. So a stagnant unemployment rate at these levels argues for stable policy.

One red flag I see is that temporary employment has stalled, suggesting some loss of momentum:

Nothing to panic about, just something I am watching. Indeed, in many ways the current dynamic is not dissimilar to the mid-90s, when the economy sputtered in the wake of tighter monetary policy. Then, like now, the Fed need to back down in response. The economy subsequently gathered steam.

Moreover, declining estimates of first quarter growth also give the Fed reason to remain on hold. Soft consumption, weaker auto sales, still anemic manufacturing, and a rising trade deficit have all conspired to bring the latest Atlanta Fed estimate of first quarter growth to an anemic 0.4%. To be sure, this might just be the first quarter curse of recent years. As such, the Fed may be confident it does not represent the pace of underlying activity. And they expect that the worst impact of the rising dollar and falling oil prices on manufacturing will soon be behind us. But they don't know these things - and it will take another three months of data at least until they know these things. That pushes that date of another rate hike into the until June at the earliest, but don't be surprised if they want to see a more complete picture of the second quarter before acting.

A steady unemployment rate at or above the Fed's estimate of the natural rate also argues for a substantial policy pause. I am hard pressed to see a reason for the Fed to resume hiking rates until unemployment clearly resumes declining. This holds true even if a growing labor force drives a flattening unemployment rate. The Fed will see that as evidence that excess slack remains in the economy, hence inflationary pressures are less than feared when the unemployment rate was heading steadily lower.

Note also tamer inflation in February after a spike the previous month:

This supports Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen's caution over reading too much into any one inflation reading.

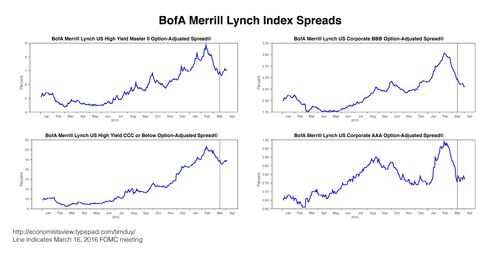

Financial indicators have firmed in recent months:

That said, the improvement for most indicators largely just offsets the damage done during the winter. And credit conditions for less than perfect debt remain less than perfect.

In short, while the data is not indicating a recession it upon us, and supportive of the case for improvement later this year, it also gives little reason to justify a rate hike anytime soon.

Furthermore, the Fed appears to have stopped - at least for the moment - pursuing rate hikes for the sake of hiking rates. The financial market turmoil made them realize that yes, the policy risks are asymmetric, and they need to take the asymmetries seriously. Chicago Federal Reserve President Charles Evans concisely summaries the challenges of being hit with a negative shock while near the zero bound:

Faced with such uncertainty, policymakers could make two potential policy mistakes. The first mistake is that the FOMC could raise rates too quickly, only to be hit by one or more of the downside surprises. In order to put the economy back on track, we would have to cut interest rates back to zero and possibly even resort to unconventional policy tools, such as more quantitative easing. I think unconventional policy tools have been effective, but they clearly are second-best alternatives to traditional policy and something we would all like to avoid. I should note, too, that with the economy facing a potentially lower growth rate and lower equilibrium interest rates, the likelihood of some shock forcing us back to the effective lower bound may be uncomfortably high. The difficulties experienced in Japan and Europe come to mind.

And compares it to the challenges of being hit with a positive shock:

The second (alternative) potential policy mistake the Committee could make is that sometime during the gradual normalization process the U.S. economy experiences upside surprises in growth and inflation. Well, policymakers have the experience and the appropriate tools to deal with such an outcome; we probably could keep inflation in check with only moderate increases in interest rates relative to current forecasts. Given how gradual the rate increases are in the baseline SEP, policy could be made a good deal more restrictive, for example, by simply increasing rates 25 basis points at every meeting — just as we did during the measured pace adjustments of 2004–06. A question for the audience: Who thinks those were fast? So, to me, concerns about the risks of rapid increases in rates in this scenario seem overblown.

Until now, the driving argument for raising rates was that they needed to do so to avoid a faster pace of rate hikes. But as Evans points out, why the rush? Would it really be so bad to raise rates at a "moderate" pace rather than a "gradual" or what has become now a "glacial" place? After all, they have better tools to reduce inflation than to raise it. Clearly, many Fed officials did not appreciate the asymmetry of risks until this past winter.

Separately, Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren argued that financial market participants are getting it wrong:

So, while problems could still arise, I would expect that the very slow removal of accommodation reflected in futures market pricing could prove too pessimistic. While it has been appropriate to pause while waiting for information that clarified the response of the U.S. economy to foreign turmoil, it increasingly appears that the U.S. has weathered foreign shocks quite well. As a consequence, if the incoming data continue to show a moderate recovery – as I expect they will – I believe it will likely be appropriate to resume the path of gradual tightening sooner than is implied by financial-market futures.

He seems to have learned little from Federal Reserve Vice-Chair Stanley Fisher's experience in January:

Well, we watch what the market thinks, but we can't be led by what the market thinks. We've got to make our own analysis. We make our own analysis and our analysis says that the market is underestimating where we are going to be. You know, you can't rule out that there is some probability they are right because there's uncertainty. But we think that they are too low .

They would probably be better off just stating their expectations as the baseline rather than appearing to challenge the markets so directly. But they can't seem to help themselves; they seem to view it as their job to warn that rate hikes are coming, that markets are getting it wrong, an unnecessarily hawkish message for a central bank trying to raise inflation while facing an asymmetric balance of risks. Not sure what the point is anyway - if Rosengren is at two rate hikes this year while the market is at one, is that difference really all that significant? Is he just priming us for Fed minutes that will also be more hawkish than current market expectations?

And the implied hawkish message has proven consistently wrong, for that matter. The history of this recovery is that while the Fed always sounds hawkish relative to market expectations, the Fed has consistently moved in the direction of market expectations.

Bottom Line: The Fed is on hold for at least a few months until the data provides a more definite reason to justify another hike. With any luck, if the Fed continues to hold steady now, maybe they will get the chance to chase the long-end of the curve higher later - which is exactly what they need to be able to "normalize" policy. Expect officials to remind us that they expect a faster pace of a rate hikes than markets anticipate. But I think the bar for further hikes has risen since December. An appreciation of the asymmetric policy risks will prod them to seek more definitive signs inflationary pressures are growing to justify the next rate hike.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Tuesday, April 5, 2016 at 04:13 PM in Economics, Fed Watch, Monetary Policy |

Permalink

Comments (10)

I have a new column:

What Bernie Sanders Gets Right: A little over a year ago, Bernie Sanders expressed one of the themes of his presidential campaign in a speech at the Brookings Institution:

We are moving rapidly away from our democratic heritage into an oligarchic form of society… billionaire families are now able to spend hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars to purchase the candidates of their choice. The billionaire class now owns the economy, and they are working day and night to make certain that they own the United States government.

This gets at the heart of the justification for our economic system. According to economic theory, one of the wonders of capitalism is that the pursuit of self-interest by individuals in society is guided, as if by an invisible hand, to maximize the collective social interest. Ruthless, cutthroat competition between individuals and businesses is magically transformed through the marketplace into a harmonious outcome that is best for society as a whole.

But there are important questions about the extent to which this describes how our economy actually works. ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Tuesday, April 5, 2016 at 05:08 AM in Economics, Fiscal Times, Politics |

Permalink

Comments (243)

Tim Taylor:

What is a "Good Job?": On the surface, it's easy to sketch what a "good job" means: having a job in the first place, along with good pay and access to benefits like health insurance. But that quick description is far from adequate, for several interrelated reasons. When most of us think about a "good job," we have more than the paycheck in mind. Jobs can vary a lot in working conditions and predictability of hours. Jobs also vary according to whether the job offers a chance to develop useful skills and a chance for a career path over time. In turn, the extent to which a worker develops skills at a given job will affect whether that worker worker is a replaceable cog who can expect only minimal pay increases over time, or whether the worker will be in a position to get pay raises--or have options to be a leading candidate for jobs with other employers. ...

When you start thinking about "good jobs" in these broader terms, the challenge of creating good jobs for a 21st century economy becomes more complex. A good job has what economists have called an element of "gift exchange," which means that a motivated worker stands ready to offer some extra effort and energy beyond the bare minimum, while a motivated employer stands ready to offer their workers at all skill levels some extra pay, training, and support beyond the bare minimum. A good job has a degree of stability and predictability in the present, along with prospects for growth of skills and corresponding pay raises in the future. We want good jobs to be available at all skill levels, so that there is a pathway in the job market for those with little experience or skill to work their way up. But in the current economy, the average time spent at a given job is declining and on-the-job training is in decline.

I certainly don't expect that we will ever reach a future in which jobs will be all about deep internal fulfillment, with a few giggles and some comradeship tossed in. As my wife and I remind each other when one of us has an especially tough day at the office, there's a reason they call it "work," which is closely related to the reason that you get paid for doing it.

But with the unemployment rate now under 5%, the main issue in the workforce isn't a raw lack of jobs--as it was in the depths of the Great Recession--but instead is about how to encourage the economy to develop more good jobs. I don't have a well-designed agenda to offer here. But what's needed goes well beyond our standard public arguments about whether firms should be required to offer certain minimum levels of wages and benefits.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Tuesday, April 5, 2016 at 05:04 AM in Economics |

Permalink

Comments (12)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Tuesday, April 5, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (236)

Larry Summers:

Data collection is the ultimate public good: On Wednesday I spoke at a World Bank conference on price statistics. While price statistics are not usually thought of as a scintillating subject, I got a great deal of satisfaction out of preparing and presenting my remarks. In part this was because my late father Robert Summers focused his economic research on International price comparisons. It was also because I am convinced that data is the ultimate public good and that we will soon have much more data than we do today. I made four primary observations.

First, scientific progress is driven more by new tools and new observations than by hypothesis construction and testing. ...

Second, if mathematics is the queen of the hard sciences than statistics is the queen of the social sciences. ...

Third, I urged that what “you count counts” and argued that we needed much more timely and complete data. ...

Fourth, I envisioned what might be possible in a world where there will soon be as many smart phones as adults. ...

This is the work of both governments and the private sector. It is fantasy to suppose data, the ultimate public good, will come into being without government effort. Equally, we will sell ourselves short if we stick with traditional collection methods and ignore innovative providers and methods such as the use of smart phones, drones, satellites and supercomputers. ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Monday, April 4, 2016 at 07:44 AM in Economics |

Permalink

Comments (35)

At MoneyWatch:

Why the Fed has a wary eye on China's economy, by Mark Thoma: Uncertainty about the global economy is making the Federal Reserve more cautious about raising U.S. interest rates. That was Fed Chair Janet Yellen's message in a speech to the Economic Club of New York last week. This uncertainty is reflected in the Fed's dialed-back forecast for rate increases this year. In December, the central bank signaled that rates would go up by 1 percent over the course of the year, but that projection dropped to a half-percent at the Fed's most recent meeting.

And when the topic is the health of the global economy, the discussion is largely about the performance of the Chinese economy. From 2002 through 2011, China's average growth rate was a remarkable 10.6 percent, according to International Monetary Fund data. But that has fallen steadily to 6.8 percent in 2015, and it's projected to slide further to 6 percent by 2017 then level off in subsequent years.

But this forecast itself has quite a bit of uncertainty. China faces several challenges that it must overcome to avoid an even lower growth rate -- and perhaps a "crash landing." ...

Posted by Mark Thoma on Monday, April 4, 2016 at 07:38 AM in China, Economics, Monetary Policy |

Permalink

Comments (34)

"Real solutions to real problems":

Cities for Everyone, by Paul Krugman, Commentary, NY Times: Remember when Ted Cruz tried to take Donald Trump down by accusing him of having “New York values”? It didn’t work, of course, mainly because it addressed the wrong form of hatred. Mr. Cruz was trying to associate his rival with social liberalism — but among Republican voters distaste for, say, gay marriage runs a distant second to racial enmity, which the Trump campaign is catering to quite nicely, thank you.

But there was another reason...: Old-fashioned anti-urban rants don’t fit with the realities of modern American urbanism. Time was when big cities could be portrayed as arenas of dystopian social collapse, of rampant crime and drug addiction. These days, however, we’re experiencing an urban renaissance. ...

Upper-income Americans are moving into high-density areas, where they can benefit from city amenities; lower-income families are moving out of such areas... You may be tempted to say, so what else is new? Urban life has become desirable again, urban dwellings are in limited supply, so wouldn’t you expect the affluent to outbid the rest and move in? ...

But living in the city isn’t like living on the beach, because the shortage of urban dwellings is mainly artificial. Our big cities ... could comfortably hold quite a few more families... The reason they don’t is that rules and regulations block construction. Limits on building height, in particular, prevent us from making more use of the most efficient public transit system yet invented – the elevator. ... And that restrictiveness brings major economic costs. ...

So there’s a very strong case for allowing more building in our big cities. The question is, how can higher density be sold politically? The answer, surely, is to package a loosening of building restrictions with other measures. Which is why what’s happening in New York is so interesting.

In brief, Mayor Bill de Blasio has pushed through a program that would selectively loosen rules on density, height, and parking as long as developers include affordable and senior housing. ...

Not everyone likes this plan. ... But it’s a smart attempt to address the issue, in a way that could, among other things, at least slightly mitigate inequality.

And may I say how refreshing it is, in this ghastly year, to see a politician trying to offer real solutions to real problems? If this is an example of New York values in action, we need more of them.

Posted by Mark Thoma on Monday, April 4, 2016 at 07:33 AM in Economics, Housing, Regulation |

Permalink

Comments (45)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Monday, April 4, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (275)

Gavyn Davies:

The internet and the productivity slump: How much would an average American, whose annual disposable income is $42,300, need to be paid in order to be persuaded to give up their mobile phone and access to the internet, for a full year? ... The question is relevant to a much more familiar issue. Why has productivity growth slowed down so much in all major economies...

Chad Syverson reckons that the unrecorded value of the digital economy to the average citizen would need to be $8400 per year in order to explain the entire productivity gap. This is one fifth of net disposable income per person. He suggests, on prima facie grounds, that few people would value their access to the digital economy at one fifth of their disposable income.

Maybe, but what is the appropriate figure? ... Faced with the choice, I doubt whether they would be prepared to be transported back to the obsolete technology of a decade ago in exchange for an annual payment of less than, say, a few thousand dollars a year...

If that conjecture (and it is no more than a conjecture) is valid, there might be something in the mismeasurement hypothesis after all. But the evidence suggests that it is not the main reason for the productivity debacle .

Posted by Mark Thoma on Sunday, April 3, 2016 at 10:33 AM in Economics, Productivity, Technology |

Permalink

Comments (110)

Posted by Mark Thoma on Sunday, April 3, 2016 at 12:06 AM in Economics, Links |

Permalink

Comments (230)

Branko Milanovic: