In this installment from the “Anarchist Current,” the Afterword to Volume Three of my anthology of anarchist writings, Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, I discuss the “Libertarians” of the late 1950s who had jettisoned any idea of a successful social revolution in favour of the idea of “permanent protest,” and the reemergence of anarchist currents in the protest movements of the 1960s.

The Impulso group was most concerned that the “new” anarchism represented by the “resistencialists” would lead anarchists away from their historic commitment to revolution, a concern not without foundation. In the 1950s in Australia, for example, the Sydney Libertarians developed a critique of anarchist “utopianism,” which for them was based on the supposed anarchist over-emphasis on “co-operation and rational persuasion” (Volume Two, Selection 41), a critique later expanded upon by post-modern anarchists (Volume Three, Chapter 12). In response, without endorsing the more narrow approach of the Impulso group, one can argue that these sorts of critiques are themselves insufficiently critical because they repeat and incorporate common misconceptions of anarchism as a theory based on an excessively naïve and optimistic view of human nature (Jesse Cohen, Volume Three, Selection 67).

For the Sydney Libertarians, not only is it unlikely that a future anarchist society will be achieved, it is unnecessary because “there are anarchist-like activities such as criticizing the views of authoritarians, resisting the pressure towards servility and conformity, [and] having unauthoritarian sexual relationships, which can be carried on for their own sake, here and now, without any reference to supposed future ends.” They described this kind of anarchism as “anarchism without ends”, “pessimistic anarchism” and “permanent protest,” stressing “the carrying on of particular libertarian activities within existing society” regardless of the prospects of a successful social revolution (Volume Two, Selection 41).

New Social Movements

The resurgence of anarchism during the1960s surprised both “pessimistic anarchists” and the more traditional “class struggle” anarchists associated with the Impulso group, some of whom, such as Pier Carlo Masini, abandoned anarchism altogether when it appeared to them that the working class was not going to embrace the anarchist cause. Other class struggle anarchists, such as André Prudhommeaux (1902-1968), recognized that the masses were “unmoved” by revolutionary declamations “heralding social revolution in Teheran, Cairo or Caracas and Judgment Day in Paris the following day at the latest,” because when “nothing is happening,” to make such claims is “like calling out the fire brigade on a hoax.” To gain the support of the people, anarchists must work with them to protect their “civil liberties and basic rights by means of direct action, civil disobedience, strikes and individual and collective revolution in all their many forms” (Volume One, Selection 30).

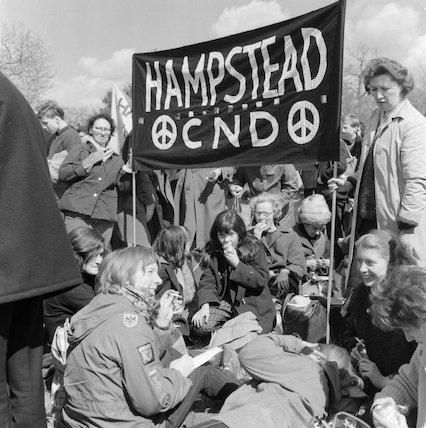

By the early 1960s, peace and anti-war movements had risen in Europe and North America in which many anarchists, following Prudhommeaux’s suggestion, were involved. Anarchist influence within the social movements of the 1960s did not come out of nowhere but emerged from the work of anarchists and like-minded individuals in the 1950s, most of whom, like Prudhommeaux, had connections with the various pre-war anarchist movements. There was growing dissatisfaction among people regarding the quality of life in post-war America and Europe and their prospects for the future, given the ongoing threat of nuclear war and continued involvement of their respective governments, relying on conscript armies, in conflicts abroad as various peoples sought to liberate themselves from European and U.S. control.

Robert Graham