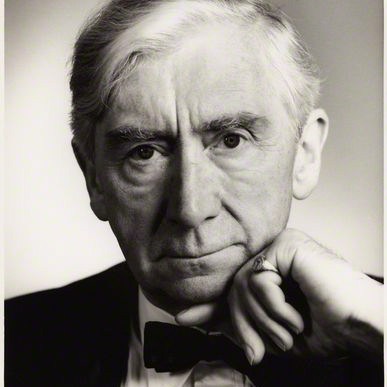

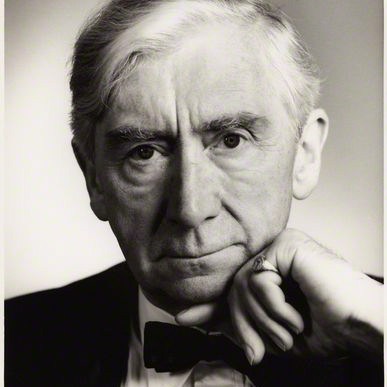

Howard Zinn: The Art of Revolution

I ended Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Ideas with excerpts from Herbert Read’s Poetry and Anarchism. I began Volume Two with excerpts from Read’s essay, “The Philosophy of Anarchism,” which helped inspire Murray Bookchin to develop his synthesis of anarchism and ecology. Both of these works are included in a collection of Read’s anarchist writings entitled, Anarchy and Order. In 1970, at the height of the Vietnam War, the celebrated American historian, Howard Zinn (1922-2010), wrote the introduction to a paperback edition. Space considerations prevented me from including it in Volume Two. Zinn’s introduction is well worth reading in its own right. It not only does an admirable job introducing both Read and anarchist ideas, it also clearly demonstrates Zinn’s own anarchist sympathies. Accordingly, I have taken the liberty of reproducing excerpts from Zinn’s introductory essay, “The Art of Revolution,” here. His words remain as relevant today as when they were written.

The Art of Revolution

The word anarchy unsettles most people in the Western world; it suggests disorder, violence, uncertainty. We have good reason for fearing those conditions, because we have been living with them for a long time, not in anarchist societies (there have never been any) but in exactly those societies most fearful of anarchy—the powerful nation-states of modern times.

At no time in human history has there been such social chaos. Fifty million dead in the Second World War. More than a million dead in Korea, a million in Vietnam, half a million in Indonesia, hundreds of thousands dead in Nigeria, and in Mozambique. A hundred violent political struggles all over the world in the twenty years following the second war to end all wars. Millions starving, or in prisons, or in mental institutions. Inner turmoil to the point of large-scale alienation, confusion, unhappiness. Outer turmoil symbolized by huge armies, stores of nerve gas, and stockpiles of hydrogen bombs. Wherever men, women, and children are even a bit conscious of the world outside their local borders, they have been living with the ultimate uncertainty: whether or not the human race itself will survive into the next generation.

It is these conditions that the anarchists have wanted to end; to bring a kind of order to the world for the first time. We have never listened to them carefully, except through the hearing aids supplied by the guardians of disorder—the national government leaders, whether capitalist or socialist.

The order desired by anarchists is different from the order (“Ordnung,” the Germans called it; “law and order,” say the American politicians) of national governments. They want a voluntary forming of human relations, arising out of the needs of people. Such an order comes from within, and so is natural. People flow into easy arrangements, rather than being pushed and forced. It is like the form given by the artist, a form congenial, often pleasing, sometimes beautiful. It has the grace of a voluntary, confident act…

The order of politics, as we have known it in the world, is an order imposed on society, neither desired by most people, nor directed to their needs. It is therefore chaotic and destructive. Politics grates on our sensibilities. It violates the elementary requirement of aesthetics—it is devoid of beauty. It is coercive, as if sound were forced into our ears at a decibel level such as to make us scream, and those responsible called this music. The “order” of modern life is a cacophony which has made us almost deaf to the gentler sounds of the universe.

The French Revolution

It is fitting that in modern times, around the time of the French and American Revolutions, exactly when man became most proud of his achievements, the ideas of anarchism arose to challenge that pride. Western civilization has never been modest in describing its qualities as an enormous advance in human history: the larger unity of national states replacing tribe and manor; parliamentary government replacing the divine right of kings; steam and electricity substituting for manual labor; education and science dispelling ignorance and superstition; due process of law canceling arbitrary justice. Anarchism arose in the most splendid days of Western “civilization” because the promises of that civilization were almost immediately broken.

Nationalism, promising freedom from outside tyranny, and security from internal disorder, vastly magnified both the stimulus and the possibility for worldwide empires over subjected people, and bloody conflicts among such empires: imperialism and war were intensified to the edge of global suicide exactly in the period of the national state. Parliamentary government, promising popular participation in important decisions, became a facade (differently constructed in one-party and two-party states) for rule by elites of wealth and power in the midst of almost-frenzied scurrying to polls and plebiscites. Mass production did not end poverty and exploitation; indeed it made the persistence of want more unpardonable. The production and distribution of goods became more rational technically, more irrational morally. Education and literacy did not end the deception of the many by the few; they enabled deception to be replaced by self-deception, mystification to be internalized, and social control to be even more effective than ever before, because now it had a large measure of self-control. Due process did not bring justice; it replaced the arbitrary, identifiable dispenser of injustice with the unidentifiable and impersonal. The “rule of law,” replacing the “rule of men,” was just a change in rulers.

Thomas Paine

In the midst of the American Revolution, Tom Paine, while calling for the establishment of an independent American government, had no illusions about even a new revolutionary government when he wrote, in Common Sense: “Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil.”

Anarchists almost immediately recognized that the fall of kings, and the rise of committees, assemblies, parliaments, did not bring democracy; that revolutions had the potential for liberation, but also for another form of despotism. Thus, Jacques Roux, a country priest in the French Revolution concerned with the lives of the peasants in his district, and then with the workingmen in the Gravilliers quarter of Paris, spoke in 1792 against “senatorial despotism,” saying it was “as terrible as the scepter of kings” because it chains the people without their knowing it and brutalizes and subjugates them by laws they themselves are supposed to have made. In Peter Weiss’s play, Marat-Sade, Roux, straitjacketed, breaks through the censorship of the play within the play and cries out:

“Who controls the markets

Who locks up the granaries

Who got the loot from the palaces

Who sits tight on the estates that were going to be divided between the poor

before he is quieted.”

A friend of Roux, Jean Varlet, in an early anarchist manifesto of the French Revolution called Explosion [Anarchism, Volume One, Selection 5], wrote:

“What a social monstrosity, what a masterpiece of Machiavellianism, this revolutionary government is in fact. For any reasoning being, Government and Revolution are incompatible, at least unless the people wishes to constitute the organs of power in permanent insurrection against themselves, which is too absurd to believe.”

Varlet: “The Explosion”

But it is exactly that which is “too absurd to believe” which the anarchists believe, because only an “absurd” perspective is revolutionary enough to see through the limits of revolution itself. Herbert Read, in a book with an appropriately absurd title, To Hell With Culture (he was seventy; this was 1963, five years before his death), wrote:

“What has been worth while in human history—the great achievements of physics and astronomy, of geographical discovery and of human healing, of philosophy and of art—has been the work of extremists—of those who believed in the absurd, dared the impossible… ”

Herbert Read

The Russian Revolution promised even more—to eliminate that injustice carried into modern times by the American and French Revolutions. Anarchist criticism of that Revolution was summed up by Emma Goldman (My Further Disillusionment in Russia, in Anarchism, Volume One, Selection 89) as follows:

“It is at once the great failure and the great tragedy of the Russian Revolution that it attempted… to change only institutions and conditions while ignoring entirely the human and social values involved in the Revolution…. No revolution can ever succeed as a factor of liberation unless the means used to further it be identical in spirit and tendency with the purposes to be achieved. Revolution is the negation of the existing, a violent protest against man’s inhumanity to man with all the thousand and one slaveries it involves. It is the destroyer of dominant values upon which a complex system of injustice, oppression, and wrong has been built up by ignorance and brutality. It is the herald of new values, ushering in a transformation of the basic relations of man to man, and of man to society.”

The institution of capitalism, anarchists believe, is destructive, irrational, inhumane. It feeds ravenously on the immense resources of the earth, and then churns out (this is its achievement—it is an immense stupid churn) huge quantities of products. Those products have only an accidental relationship to what is most needed by people, because the organizers and distributors of goods care not about human need; they are great business enterprises motivated only by profit. Therefore, bombs, guns, office buildings, and deodorants take priority over food, homes, and recreation areas. Is there anything closer to “anarchy” (in the common use of the word, meaning confusion) than the incredibly wild and wasteful economic system in America?

Emma Goldman

Anarchists believe the riches of the earth belong equally to all, and should be distributed according to need, not through the intricate, inhuman system of money and contracts which have so far channeled most of these riches into a small group of wealthy people, and into a few countries. (The United States, with six percent of the population, owns, produces, and consumes fifty percent of the world’s production.) They would agree with the Story Teller in Bertholt Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle, in the final words of the play:

“Take note what men of old concluded:

That what there is shall go to those who are good for it

Thus: the children to the motherly, that they prosper

The carts to good drivers, that they are well driven

And the valley to the waterers, that it bring forth fruit.”

It was on this principle that Gerard Winstanley, leader of the Diggers in 17th century England, ignored the law of private ownership and led his followers to plant grain on unused land. Winstanley wrote about his hope for the future [in Anarchism, Volume One, Selection 3]:

“When this universal law of equity rises up in every man and woman, then none shall lay claim to any creature and say, This is mine, and that is yours, This is my work, that is yours. But every one shall put to their hands to till the earth and bring up cattle, and the blessing of the earth shall be common to all; when a man hath need of any corn or cattle, take from the next storehouse he meets with. There shall be no buying and selling, no fairs or markets, but the whole earth shall be a common treasury for every man, for the earth is the Lord’s.”

Anarchy: Against the Machine

Our problem is to make use of the magnificent technology of our time, for human needs, without being victimized by a bureaucratic mechanism. The Soviet Union did show that national economic planning for common goals, replacing the profit-driven chaos of capitalist production, could produce remarkable results. It failed, however, to do what Herbert Read and other recent anarchists have suggested: to do away with the bureaucracy of large-scale industry, characteristic of both capitalism and socialism, and the consequent unhappiness of the workers who do not feel at ease with their work, with the products, with their fellow workers, with nature, with themselves. This problem could be solved, Read has suggested, by workers’ control of their own jobs, without sacrificing the benefits of planning and coordination for the larger social good.

“Property is theft,” Proudhon wrote in the mid-19th century (he was the first to call himself an anarchist, Anarchism, Volume One, Selection 8). Whether the resources of the earth and the energies of men are controlled by capitalist corporations or bureaucracies calling themselves “socialist,” a great theft of men’s life-work has occurred, as a kind of original sin which has led in human history to all sorts of trouble: exploitation, war, the establishment of colonies, the subjugation of women, attacks on property called “crime,” and the cruel system of punishments which all “civilized societies” have erected, known as “justice.”

Both the capitalist and the socialist bureaucracies of our time fail, anarchists say, on their greatest promise: to bring democracy. The essence of democracy is that people should control their own lives, by ones or twos or hundreds, depending on whether the decision being made affects one or two or a hundred. Instead, our lives are directed by a political-military- industrial complex in the United States, and a party hierarchy in the Soviet Union. In both situations there is the pretense of popular participation, by an elaborate scheme of voting for representatives who do not have real power (the difference between a one-party state and a two-party state being no more than one party—and that a smudged carbon copy of the other). The vote in modern societies is the currency of politics as money is the currency of economics; both mystify what is really taking place—control of the many by the few.

Anarchists believe the phrase “law and order” is one of the great deceptions of our age. Law does not bring order, certainly not the harmonious order of a cooperative society, which is the best meaning of that word. It brings, if anything, the order of the totalitarian state, or the prison, or the army, where fear and threat keep people in their assigned places. All law can do is artificially restrain people who are moved to acts of violence or theft or disobedience by a bad society. And the order brought by law is unstable, always on the brink of a fall, because coercion invites rebellion. Laws cannot, by their nature, create a good society; that will come from great numbers of people arranging resources and themselves voluntarily (“Mutual Aid,” Kropotkin called it, Anarchism, Volume One, Selection 54) so as to promote cooperation and happiness. And that will be the best order, when people do what they must, not because of law, but on their own.

What has modern civilization, with its “rule of law,” its giant industrial enterprises, its “representative democracy,” brought? Nuclear missiles already aimed and ready for the destruction of the world, and populations—literate, well-fed, and constantly voting—of a mind to accept this madness. Civilization has failed on two counts: it has perverted the natural resources of the earth, which have the capacity to make our lives joyful, and also the natural resources of people, which have the potential for genius and love.

Making the most of these possibilities requires the upbringing of new generations in an atmosphere of grace and art. Instead, we have been reared in politics. Herbert Read (in Art and Alienation) describes the stunted human being who emerges from this:

Making the most of these possibilities requires the upbringing of new generations in an atmosphere of grace and art. Instead, we have been reared in politics. Herbert Read (in Art and Alienation) describes the stunted human being who emerges from this:

“If seeing and handling, touching and hearing and all the refinements of sensation that developed historically in the conquest of nature and the manipulation of material substances are not educed and trained from birth to maturity the result is a being that hardly deserves to be called human: a dull-eyed, bored and listless automaton whose one desire is for violence in some form or other—violent action, violent sounds, distractions of any kind that can penetrate to its deadened nerves. Its preferred distractions are: the sports stadium, the pin-table alleys, the dance-hall, the passive ‘viewing’ of crime, farce and sadism on the television screen, gambling and drug addiction.”

What a waste of the evolutionary process! It took a billion years to create human beings who could, if they chose, form the materials of the earth and themselves into arrangements congenial to man, woman, and the universe. Can we still choose to do so?

It seems that revolutionary changes are needed—in the sense of profound transformations of our work processes, our decision- making arrangements, our sex and family relations, our thought and culture—toward a humane society. But this kind of revolution—changing our minds as well as our institutions— cannot be accomplished by customary methods: neither by military action to overthrow governments, as some tradition-bound radicals suggest; nor by that slow process of electoral reform, which traditional liberals urge on us. The state of the world today reflects the limitations of both those methods.

Anarchists have always been accused of a special addiction to violence as a mode of revolutionary change. The accusation comes from governments which came into being through violence, which maintain themselves in power through violence, and which use violence constantly to keep down rebellion and to bully other nations. Some anarchists—like other revolutionaries throughout history, whether American, French, Russian, or Chinese—have emphasized violent uprising. Some have advocated, and tried, assassination and terror. In this they are like other revolutionaries—of whatever epoch or ideology. What makes anarchists unique among revolutionaries, however, is that most of them see revolution as a cultural, ideological, creative process, in which violence would be as incidental as the outcries of mother and baby in childbirth. It might be unavoidable—given the natural resistance to change—but something to be kept at a minimum while more important things happen.

Alexander Berkman, who as a young man attempted to assassinate an American industrialist, expressed his more mature reflections on violence and revolution in The ABC of Anarchism [Anarchism, Volume One, Selection 117]:

“What, really, is there to destroy?

The wealth of the rich? Nay, that is something we want the whole of society to enjoy.

The land, the fields, the coal mines, the railroads, factories, mills and shops? These we want not to destroy but to make useful to the entire people.

The telegraphs, telephones, the means of communication and distribution—do we want to destroy them? No, we want them to serve the needs of all.

What, then, is the social revolution to destroy? It is to take over things for the general benefit, not to destroy them. It is to reorganize conditions for the public welfare.”

Revolution in its full sense cannot be achieved by force of arms. It must be prepared in the minds and behavior of men, even before institutions have radically changed. It is not an act but a process. Berkman describes this:

“If your object is to secure liberty, you must learn to do without authority and compulsion. If you intend to live in peace and harmony with your fellow men, you and they should cultivate brotherhood and respect for each other. If you want to work together with them for your mutual benefit, you must practice co-operation. The social revolution means much more than the reorganization of conditions only: it means the establishment of new human values and social relationships, a changed attitude of man to man, as of one free and independent to his equal; it means a different spirit in individual and collective life, and that spirit cannot be born overnight. It is a spirit to be cultivated, to be nurtured and reared, as the most delicate flower is, for indeed it is the flower of a new and beautiful existence… We must learn to think differently before the revolution can come. That alone can bring the revolution.”

Alexander Berkman

The anarchist sees revolutionary change as something immediate, something we must do now, where we are, where we live, where we work. It means starting this moment to do away with authoritarian, cruel relationships—between men and women, between parents and children, between one kind of worker and another kind. Such revolutionary action cannot be crushed like an armed uprising. It takes place in everyday life, in the tiny crannies where the powerful but clumsy hands of state power cannot easily reach. It is not centralized and isolated, so that it can be wiped out by the rich, the police, the military. It takes place in a hundred thousand places at once, in families, on streets, in neighborhoods, in places of work. It is a revolution of the whole culture. Squelched in one place, it springs up in another, until it is everywhere.

Such a revolution is an art. That is, it requires the courage not only of resistance, but of imagination. Herbert Read, after pointing out that modern democracy encourages both complacency and complicity, speaks (in Art and Alienation) of the role of art:

“Art, on the other hand, is eternally disturbing, permanently revolutionary. It is so because the artist, in the degree of his greatness, always confronts the unknown, and what he brings back from that confrontation is a novelty, a new symbol, a new vision of life, the outer image of inward things. His importance to society is not that he voices received opinions, or gives clear expression to the confused feelings of the masses: that is the function of the politician, the journalist, the demagogue. The artist is what the Germans call ein Ruttler, an upsetter of the established order.”

This should not be interpreted as an arrogant distinction be tween the elite artist and the mass of people. It is, rather, a recognition that in modern society, as Herbert Marcuse has pointed out, there is enormous pressure to create a “one dimensional mind” among masses of people, and this requires upsetting.

Herbert Read’s attraction to both art and anarchy seems a fitting response to the 20th century, and underscores the idea that revolution must be cultural as well as political. The title of his book To Hell With Culture might be misinterpreted if one did not read in it:

Herbert Read’s attraction to both art and anarchy seems a fitting response to the 20th century, and underscores the idea that revolution must be cultural as well as political. The title of his book To Hell With Culture might be misinterpreted if one did not read in it:

“Today we are bound hand and foot to the past. Because property is a sacred thing and land values a source of untold wealth, our houses must be crowded together and our streets must follow their ancient illogical meanderings… Because everything we buy for use must be sold for profit, and because there must always be this profitable margin between cost and price, our pots and our pans, our furniture and our clothes, have the same shoddy consistency, the same competitive cheapness. The whole of our capitalist culture is one immense veneer: a surface of refinement hiding the cheapness and shoddiness of the heart of things.

To hell with such a culture. To the rubbish-heap and furnace with it all! Let us celebrate the democratic revolution creatively. Let us build cities that are not too big, but spacious, with traffic flowing freely through their leafy avenues, with children playing safely in their green and flowery parks, with people living happily in bright efficient houses… Let us balance agriculture, and industry, town and country—let us do all these sensible and elementary things and then let us talk about culture.”

The anarchist tries to deal with the complex relationship between changing institutions and changing culture. He knows that we must revolutionize culture starting now; and yet he knows this will be limited until there is a new way of living for large numbers of people. Read writes in the same essay: “You cannot impose a culture from the top—it must come from under. It grows out of ‘the soil, out of the people, out of their daily life and work. It is a spontaneous expression of their joy in life, of their joy in work, and if this joy does’ not exist, the culture will not exist.”

For revolutionaries, the aesthetic element—the approach of the artist—is essential in breaking out of the past, for we have seen in history how revolutions have been cramped or diverted because the men who made them were still encumbered by tradition. The warning of Marx, in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, needs to be heeded by Marxists as well as by others seeking change:

“The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. And just when they seem engaged in revolutionizing themselves and things, in creating something entirely new, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service and borrow from them names, battle slogans and costumes in order to present the new scene of world history in this time-honoured disguise and this borrowed language.”

The art of revolution needs to go beyond what is called “reason,” and what is called “science,” because both reason and science are limited by the narrow experience of the past. To break those limits, to extend reason into the future, we need passion and instinct, coming out of those depths of human feeling which escape the bounds of a historical period. When Read spoke in London in 1961, before taking part in a mass act of civil disobedience in protest against Polaris nuclear submarines, he argued for breaking out of the limits of “reason” through action:

“This stalemate must be broken, but it will never be broken by rational argument. There are too many right reasons for wrong actions on both sides. It can be broken only by instinctive action. An act of disobedience is or should be collectively instinctive—a revolt of the instincts of man against the threat of mass destruction.

Instincts are dangerous to play with, but that is why, in the present desperate situation, we must play with instincts…

We must release the imagination of the people so that they become fully conscious of the fate that is threatening them, and we can best reach their imagination by our actions, by our fearlessness, by our willingness to sacrifice our comfort, our liberty, and even our lives, to the end that mankind shall be delivered from pain and suffering and universal death.”

Anarchism seeks that blend of order and spontaneity in our lives which gives us harmony with ourselves, with others, with nature. It understands the need to change our political and economic arrangements to free ourselves for the enjoyment of life. And it knows that the change must begin now, in those everyday human relations over which we have the most control. Anarchism knows the need for sober thinking, but also for that action which clarifies otherwise academic and abstract thought.

Herbert Read, in “Chains of Freedom,” writes that we need a “Black Market in culture, a determination to avoid the bankrupt academic institutions, the fixed values and standardized products of current art and literature; not to trade our spiritual goods through the recognized channels of Church, or State, or Press; rather to pass them ‘under the counter’.” If so, one of the first items to be passed under the counter must surely be the literature that speaks, counter to all the falsifications, about the ideas and imaginings of anarchism.

Howard Zinn

Boston, October 1970