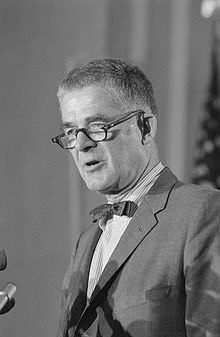

Archibald Cox

| Archibald Cox | |

|---|---|

|

|

| 31st United States Solicitor General | |

| In office January 1961 – July 1965 |

|

| President | John F. Kennedy Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | J. Lee Rankin |

| Succeeded by | Thurgood Marshall |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Archibald Cox, Jr. May 17, 1912 Plainfield, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | May 29, 2004 (aged 92) Brooksville, Maine, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Phyllis Ames Cox (June 13, 1937-his death). |

| Children | Sarah, Archibald, Jr. and Phyllis |

| Alma mater | Harvard College (B.A., 1934) Harvard Law School (J.D., 1937) |

Archibald Cox, Jr. (May 17, 1912 – May 29, 2004) was an American lawyer, legal scholar and professor, whose career alternated between academia and government. As a faculty member at the Harvard Law School, he became one of the early experts in federal labor law. He published the first case book on labor law for use in law schools, a book that was periodically updated and supplemented until 2011. He was a prolific writer, publishing dozens of articles on developments in labor relations. He also became a noted labor arbitrator, even while continuing to teach.

He became a supporter, adviser and speech writer for Senator John F. Kennedy and supported his bid for the presidency. He was rewarded by being appointed in 1961 as Solicitor General, an office he held for four and a half years during which time he briefed and argued some of the most consequential decisions of the Warren Court. On return to Harvard he expanded on his experience in government to write on and teach constitutional law. He dealt with the student disorders at Harvard, and chaired the blue ribbon commission that investigated the causes of the student strikes that closed down Columbia.

Cox became internationally famous when under mounting pressure and charges of corruption, President Richard Nixon was forced to appoint him (on account of his reputation for integrity and his independence from the President) as Special Prosecutor to oversee the federal criminal investigation into the Watergate burglary and other related crimes, corrupt activities and wrongdoings that became popularly known as the Watergate scandal. His investigation led him directly to the President himself, and he had a dramatic confrontation with Nixon when he subpoenaed the tapes the President had secretly recorded of his Oval Office conversations. When Cox refused a direct order to withdraw the subpoena, Nixon fired him in an incident that became known as the Saturday Night Massacre. Cox's calm, reasonable and impeccably dignified explanations of his positions earned him overwhelming support among the professional bar and a great deal of popularity among the country at large. His firing produced a public relations disaster for Nixon and set in motion impeachment proceedings. In the end, the United States Supreme Court ruled unanimously against the President and in favor of the position taken by Cox in an opinion written by Nixon appointee Chief Justice Warren Burger. Rather than face impeachment and trial with the tapes as evidence, Richard Nixon became the only United States President to resign.

Cox returned to teaching, lecturing and writing for the rest of his life, giving his opinions on the role of the court in the development of the law and the role of the lawyer in society. He was appointed to head several public-service, watchdog and good-government organizations, including serving for 12 years as head of Common Cause. In addition he argued two important Supreme Court cases, winning both: one concerning the constitutionality of federal campaign finance restrictions and the other the first case testing affirmative action. The New York Times summarized his career in a 1992 opinion: "Mr. Cox devoted his considerable prestige, energy, and legal skills to advancing the cause of higher government ethics. With public trust in government at a dangerously low ebb, Mr. Cox's message is more powerful than ever."[1]

Contents

- 1 Early life, education and private practice

- 2 Government service and early academic career

- 3 Wage controller and foremost academic expert in labor law

- 4 Advisor to Senator Kennedy and Role in the Kennedy Administration

- 5 Watergate special prosecutor

- 6 Post-Watergate career

- 7 Family life and death

- 8 Honors

- 9 Select Publications

- 10 Notes and references

- 11 Sources and further reading

- 12 External links

Early life, education and private practice[edit]

Family and ancestors[edit]

Cox was born in Plainfield, New Jersey, the son of Archibald and Frances "Fanny" Bruen Perkins Cox, the eldest of seven children.[a] His father Archibald Sr. (Harvard College, 1896; Harvard Law School, 1899[3]) was the son of a Manhattan lawyer who rose to prominence as a patent and trademark lawyer, and who wrote Cox's Manual on Trade Marks.[4] [b] When Rowland Cox died suddenly in 1900 Archibald Sr. inherited his father's solo practice almost right out of law school. He built on that start to become successful in his own right.[5] His most prominent achievement was securing the red cross as the trademark of Johnson & Johnson.[6] Compared to the lawyers on his mother's side, his father (as Archibald Jr. reflected late in his life) did not did not participate much in public service, although he had "done a few things for Woodrow Wilson … at the time of the peace conference" and was President of the local Board of Education.[7] He also served as a member of the New Jersey Rapid Transit Commission.[3]

Cox's mother Fanny was the granddaughter of two equally eminent (in entirely different fields) men. Charles C. Perkins, the son of a wealthy merchant, never had need to earn money his entire life. So after Harvard, he studied drawing in Rome, established a studio in Paris and studied art history in Leibzig. Back in New England he dabbled in music, composing, presiding over the Handel and Haydn Society and becoming the largest subscriber to Boston Music Hall. Later he lectured and published books on art history and became one of the founders of Boston's Museum of Fine Arts.[8][9] His grandson Maxwell Perkins, Cox's uncle, was the famed editor at the publishing house of Charles Scribner's Sons.[10] In August 1886 Fanny's grandfather Perkins died on being thrown from a carriage while driving with Fanny's other grandfather William M. Evarts near his estate in Windsor, Vermont.[11] [c]

It was Fanny's grandfather Evarts who was to become the ancestor that loomed largest over Cox's youth. He was a direct descendant of founding father Roger Sherman, a Connecticut signer of the Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution. But more importantly Evarts, a much acclaimed New York litigator in the second half of the nineteenth century (who would go on to become United States Attorney General, Secretary of State and Senator from New York), had been involved in a number of the great political litigations of his time, beginning with his defense of President Andrew Johnson in the trial of his impeachment in the Senate. Evarts, a devoted Republican, nevertheless faced down what seemed to be the unstoppable determination of the Republicans to oust the Democrat and accidental President.[13] The acquittal he achieved in the Senate was a point of comparison when Archibald Cox investigated another President a century later. Cox heard early on stories of Evarts's involvement in the famous Lemmon Slave Case and others.[14] Evarts had built six mansions (one for each of his children) on his property in Windsor, where he was a local legend in Cox's time. Cox's grandmother Elizabeth Perkins was given the property later known as Runnemeade Lodge. It was here that Archibald Cox spent each of his summers (beginning when he was less than a month old[15]) until his family's circumstances changed when he was in college. This was where Cox developed his affinity for things New England and absorbed his New England mannerisms. The summer scene in Windsor and nearby Cornish, New Hampshire was the resort for numerous figures of turn of the century culture. It was also where the numerous lawyers (including Fanny's father Edward Clifford Perkins) connected with the Evarts were encountered.[16] Cox summarized these influences in an interview on C-SPAN in 1987: "I grew up in a legal family. My ancestors on both sides were lawyers, and it's hard to think of a time when I wasn't going to be a lawyer."[17]

In Plainfield, where he spent non-summer months, Cox and his family lived in patrician affluence, his home, a Dutch colonial built on a 9-acre plot, featured a tennis court, maids quarters and an apartment above the garage for the chauffeur. As for the family's relations with the staff, Cox later said: "I think that the relations between my family and the 'retainers' were very good. At least that's my picture. But the symbols of status were probably much more important than any ideas of status themselves."[18] Fanny donated her time to community activities, typical of her class; for example, to the local garden club and as member of the Muhlenberg Hospital Women's Auxiliary.[19] In one respect only was the Cox family unlike the upper tier professionals they lived among: the Coxes supported Democrat (and Catholic) candidate Al Smith against Herbert Hoover in 1928.[20]

Preparatory education[edit]

Cox Sr. had definite ideas of the educational path Archie would follow; it was the same path the he as well as the Perkins and Evarts had followed. And while Archie did not object to the plan, Cox Sr. sometimes despaired Cox would be accepted at the right institutions. Archie was sent attended the private Wardlaw School in Edison, New Jersey until he was fourteen.[21] When it came time to apply to St. Paul's School in New Hampshire, Cox Sr. chanced to read a school project of Archie's and finding misspellings and other mistakes he exclamed to his wife: "Well, the boy's a moron." To avert disaster he wrote to an administrator of the school on April 1926 to point out how many of Archie's near relatives (grandparents, uncles) were alumni of St. Paul's and how his great-grandfather Perkins was an important trustee.[22] His son was duly admitted. Cox Sr. would repeat the intervention when Archie was applying to Harvard. Cox Sr. prevailed on his friend Judge Learned Hand to write a recommendation (although he did not know the boy).[23] Cox would later tell an interviewer of the fact that kept his career on an upward trajectory: "You've only to look at me to see that I have family connections to Harvard, to the Eastern Establishment."[17]

Cox thrived at St. Paul, situated in rural New England only 60 miles from Windsor and populated by the sons of the "Eastern Establishment." His courses were standard for a top shelf boys school, including Greek, Latin, English and American history, literature and "some science." He also had a regular dosage of Episcopalian religion.[24] The rigorous discipline, spartan conditions and strict schedules seemed to invigorate him and developed in him a sense of camaraderie with his classmates. Most notably he developed as a strong public presenter. In his final year he won Hugh Camp Memorial Cup for public speaking and lead the school's debate team to defeat Groton[25] It was during this period that he read Beveridge's Life of John Marshall, which was an important early ingredient in Cox's progressive view of the law.[26] With a warm recommendation from the head-master (and family connections), Cox was able to enter Harvard College in 1930.

Harvard[edit]

College[edit]

Cox, Sr. advised Archie of the relative value of the different educations he would receive: "You go to college to grow up. When you go to law school, you’ll have begun your career."[27] So he approached Harvard College with a carefreeness he would not be known for later. He joined of Harvard's Finals Club, the Delphic Club, nicknamed then as the "Gashouse" for the parties, gambling and liquor (during Prohibition).[28] He majored in History, Government and Economics and did slightly better than "gentlemanly Cs."[29]

It was during the second semester of his freshman year that his life changed. In February his father died at 56.[3] His mother was devastated emotionally and financially. In the midst of the Depression she was forced to take in boarders, and write to St. Paul to request financial assistance for her son Robert's tuition. For Archie summers at Windsor would end, and he was forced to take summer work, the first year as a tutor with the family of the doctor who had tended to his dying father (to whom the family's horse was also sold). The tragedy also affected Cox's grades, although allowance for his father's death was noted in the official records.[30] Cox would experience another tragedy in his junior year. He had developed a serious relationship with Radcliffe student named Connie Holmes. He had even introduced her to his family. That fall she suffered an attack and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital outside of Cambridge. On her release, her mother took her to Europe for convalescence. Toward the end of his junior year Cox received word that Connie had committed suicide with sleeping pills in France. The news delivered a shock and loss from which he remembered throughout his life.[31]

During Cox's senior year he was able to give his full attention to academics. For his senior thesis he had proposed analyzing the constitutional differences of the composition of the Senate and House through early American history. His advisor, Paul Buck, told him he didn't "have brains enough" for the project. Cox took up the challenge and completed Senatorial Saucer.[d] As a result of the work Cox was able to graduate with honors in History.[33]

Law School[edit]

It was at law school that Cox began to thrive. Withdrawing from most social activities he was initiated into the intricacies of legal thinking and inspired to hard work by legendary professor Roscoe Pound. He ranked first in his class of 593 at the end of his first year.[34] During his first year, Cox also engaged in partisan politics for the first time. He volunteered to go door-to-door in support of the gubernatorial candidacy of Lieutenant Governor Gaspar Bacon against once convicted and many times investigated Boston Mayor James Michael Curley. Bacon's defeat (by a substantial plurality) taught Cox lessons about class and ethnic politics.[35]

Cox's second year was taken up with work on the Harvard Law Review. He also met his future wife Phyllis Ames. Cox proposed to her after only three or four meetings. She initially put him off, but by March 1936 they were engaged.[36] Phyllis, who graduated Smith the year before, was the granddaughter of James Barr Ames, one time dean of Harvard Law School and noted for popularizing the casebook method of legal study.[8] She was also niece of Robert Russell Ames, whose death two years previously in a yacht racing accident, together with the deaths of his two sons attempting to rescue him, was widely reported.[37] [e] On her paternal side Phyllis Ames was granddaughter of legal scholar Nathan Abbott, who among other things, was a founder of Stanford Law School. Professor (and later United States Associate Justice) Felix Frankfurter wrote them a congratulatory note on their betrothal, which exclaimed: "My God, what a powerful legal combination!"[39]

Not long after, Professor Frankfurter gave Cox the first big opportunity of his career. Cox's ambitions were not particularly high in his third year. He had resigned from the Law Review at the end of his second year owing to eye problems, and so he was no longer in the "center of things." In the first semester of his third year he had agreed with Phyllis to take a job in Boston and was considering a corporate law firm. Unlike other "high standers" he had not applied for Frankfurter's highly sought after Federal Jurisdiction course, even though Frankfurter's insider status as confidant to President Roosevelt made him especially important as an entre into the higher reaches of the Executive Branch. But Cox did take Frankfurter's Public Utilities course, in which he was, as a Sears Prize winner, frequently called on by Frankfurter. Even so, he was surprised when Frankfurter called him to his office and offered Cox a clerkship with Judge Learned Hand, then on the Second Circuit.[40] [f] Phyllis agreed that it was a job that could not be rejected, so they planned on moving to New York for the clerkship after Cox graduated.

Cox graduated in 1937 magna cum laude, one of nine receiving the highest honor awarded by the law school that year.[41] Two weeks before his commencement, Cox and Phyllis married.[42]

Law clerkship[edit]

Cox's clerkship with Hand was more like an apprenticeship. Hand did everything himself; he did not allow his clerks to even write a draft of the facts of the case. Cox sat in the same room, read the same briefs and cases, but only spoke when Hand addressed him. He would allow Cox to copy edit his opinions, but only after Hand would make three or four drafts. And if Cox had no comments on a draft given to him, Hand would tell him, "No pay today, Sonny."[43] Cox had difficulty later in life explaining why Hand such a profound effect on him. He suggested it was the levity that the public never saw. Or his occasional unexpected acts of kindness. His exacting demands for perfection and the hard work he put in to achieve it. But it was more of a view point. Hand instilled in him a profound respect for the legal tradition, but a respect tempered by a progressive's understanding of the role of courts in modern society. Cox later described a major influence of Judge Hand on American law as "both in breaking down the restrictions imposed by the dry literalism of conservative tradition and in showing how to use with sympathetic understanding the information afforded by the legislative and administrative processes."[44] Cox explained what his "great teacher" taught him about the "legitimacy" of law: "The judge must wrap himself in the mantle of an overshadowing path. He must show that he too is bound by law." More personally Cox said: "He was more of a philosopher than most judges. I think he greatly shaped my outlook on life in ways that are very hard to express."[17]

Private practice[edit]

A year in New York City proved enough for both Archie and Phyllis, so Cox accepted an associate position with the Boston law firm of Ropes, Gray, Best, Coolidge and Rugg, now known as Ropes & Gray. In the three years he practiced there he had two important mentors., both of whose practice was in labor law The first was Charlie Rugg, who was the first to show him how briefs should be written and also gave him his first experience in union recognition negotiations (and without supervision, at that). The second was Charlie Wyzanski. Wyzanski was a Hand clerk who also early joined the New Deal, where he garnered early experience with the National Labor Relations Act (NLRB or Wagner Act) in the Labor Department and then moved to the solicitor general's office. It was a time of great ferment in the field, especially as organizational activity notably by the textile workers was returning in New England.[45]

At Ropes, Gray Cox appeared regularly for motion practice in the Superior Court in Boston, tried "one or two" cases before a judge and argued a case before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.[46] It was Wyzanski, however, who would have the biggest influence on his early career.

As the war in Europe became increasingly ominous for the Western democracies, Cox and his family came to believe that American assistance was vital. Cox's younger brother Robert had left Harvard to join the King's Royal Rifle Corps.[47] Shortly after the National Defense Mediation Board ("NDMB") was established in March 1941, President Roosevelt appointed Wyzanski its vice chairman. The Board was designed to mediate labor disputes in industries affected by the defense-related industrial boom. In June Wyzanski asked Cox to become one of the Boards four assistants. Cox accepted and moved to Washington, D.C., with Phyllis and their two children in what would be the first of his many stints of service to the national government.[48]

Government service and early academic career[edit]

Wartime government service[edit]

National Defense Mediation Board[edit]

Although the NDMB had been designed with the hope of preventing work stoppages in labor disputes, it was given only the power to assist in voluntary means of resolving disputes and making public findings of fact. The Board itself took the soon-to-be familiar "tri-partite" composition of representatives of industry and labor (four each) and three "neutral" public appointees. From the start it was criticized for not having the ability to forestall strikes, on the one hand, and of unnecessarily curtailing labor's negotiating ability, on the other.[49] It did not take long before the board"came to grief," as Cox (who rose to the rank of Principal Mediation Officer) put it. United Mine Workers boss John L. Lewis stymied the Board's attempt to intervene in the case of the "captive" coal mines (those owned by steel mills). In that case the union was seeking a closed shop, requiring mine owners to hire only union workers. The board (including the two A.F.L. members) recommended against inclusion of the closed shop clause.[50] Backing Lewis, C.I.O. members withdrew from the Board, and Lewis defied the government's threat to use troops to resolve the strike. At this point the NDMB "ceased to function as a board."[51] Eventually the President brokered binding arbitration, which in the end backed the union's position.[52] [g] With entry into the war imminent, Roosevelt dismantled the NMDB.

Wyzanski had been appointed to the federal bench in Massachusetts at the beginning of December, and Cox, who was unable to work with Board chairman William Hammatt Davis ("we never hit it off"), felt abandoned.[53] But through the intervention of Judge Hand (not disclosed to Cox), Cox was offered a position in the solicitor general's office.[54]

Solicitor general's office[edit]

At the solicitor general's office Cox was the least senior of the seven or eight assistants who worked for Charles Fahy. It was nevertheless prestigious simply to work there, and the lawyers had much independence. The bulk of Cox's work involved reviewing decisions by various divisions of the Department of Justice (Civil, Tax, Lands, Antitrust and Criminal) as to whether to seek review by the Supreme Court of Circuit Court cases or certioriari of decisions relating to the independent federal agencies (the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), S.E.C., and the I.C.C.). Cox generally submitted his reports to the first assistant. He also was assigned Supreme Court briefs or petitions for the Supreme Court written by attorneys in the Attorney General's office. Cox would edit or re-write the briefs before Fahy or his clerk would review them. Fahy also had Cox argue an NLRB case in the Circuit Court.[56] The most memorable case, he would repeatedly say, was the first case he appeared before the Supreme Court, merely to confess error.[57] The Court however affirmed 4-4, and Cox was able much later to say that he was the only attorney to lose both his first and last case before the Supreme Court by split decisions.[58]

Notwithstanding the challenging work, Cox was restless. He had come to Washington to aid in the war effort, and he felt vague guilt that his brother was serving in North Africa and he was not doing his part. Toward the end of the Court's session in 1943, Fahy "released" Cox when an opportunity arose to work in the Office of Foreign Economic Coordinator (OFEC).[59]

With Finletter at the State Department[edit]

Thomas K. Finletter came to Washington as a special assistant to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and he became director of the OFEC, which dealt with procurement of strategic materials from neutral countries and other matters relating to foreign funds. Most interesting to Cox was that he acted as the head of a Combined Allied. Committee on North Africa.[60] When Robert Cox learned of Cox's transfer he harbored vague hope that Archie would be sent to North Africa where they could meet, but it was not to be as Robert was killed shortly after Cox took the new position.[61]

Th position at the State Department also did not last long. Cox surmised that Finletter "was a little too ambitious." He had hopes that he would become responsible for economic aspects of reoccupied Europe. Instead the incoming cables stopped being routed to him—the way the State Department signals the end of a project.[62] At the end of 1943 Cox received a call from Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins who offered Cox the job of associate solicitor of the Labor Department.[63] Once again the offer was almost certainly owing to the intercession of Judges Hand and Wyzanski.[64]

Solicitor in the Labor Department[edit]

As associate solicitor Cox's job in the Labor Department was to supervise enforcement at the District Court level of federal labor statutes. Cox had a staff of eight lawyers in Washington and supervised the Department's regional offices, including deciding when a regional attorney could bring suit. Most of the litigation involved wage and hours issues under the Fair Labor Standards Act. His background in the solicitor general's office also allowed him to handle much of the appellate work.[65] By virtue of his position Cox also occasionally sat as an alternate public member of the Wage Adjustment Board, which a specialized subsidiary of the National War Labor Board which dealt with the construction industry and attempted to maintain labor peace by mediating non-wage disputes and setting prevailing wage rates and increases under the Davis–Bacon Act.[66]

Cox stayed in this position until Perkins left in the summer of 1945. The war in Europe was over, the war in the Pacific was soon to be, and Archie and Phyllis decided to return to Boston. The offer at Ropes, Grey was still open.[67]

Harvard faculty and labor arbitrator[edit]

Cox returned to Ropes, Gray with the intention of spending his professional career there. Instead, he lasted five weeks.[17] Dean Landis of the Harvard Law School offered to hire Cox as a probationary teacher in the fall of 1945. Cox accepted, despite the substantial cut in salary he would take, but on the condition that he would not have to teach corporations or property. Landis agreed; his expectation was that Cox should become a nationally recognized expert in labor law.[68] In addition to labor law, Cox started out teaching torts. Later he would also teach unfair competition, agency and administrative law.[69] He was made a permanent professor during the 1946-47 academic year, a time when the law school greatly increased enrollment in the post-war boom.[70] During the 1947-48 Term Cox also volunteered for appointment by the Supreme Court to represent indigent defendants and was appointed in two cases of prisoners from the Eastern Pennsylvania Penitentiary in Philadelphia.[71] In one case he obtained a reversal on the ground that the defendant had been deprived assistance of counsel during sentencing phase, where a lawyer might have prevented a the misreading of the defendants' previous record.[72] [h] In the other case the Court affirmed, over four dissents, the possibly erroneous application of Pennsylvania's habitual offenders statute, even though the defendant was unrepresented at sentencing.[75] He also became a frequent panelist at legal and judicial conferences.

Cox first began writing articles on labor issues for peer reviewed journals in 1947. Over time this writing would become a prolific body of work. The same year he became a member of the National Panel of Arbitrators of the American Arbitration Association and began a long career as a labor arbitrator. The proceedings in which Cox sat ranged "from local level confrontations such as those brought by specific school boards to major interstate cases such as Consolidated Edison Co. of New York and New England Petroleum Corporation." The labor disputes usually involved wage, hiring, promotion, and dismissal grievances.[76] In 1948 he published the first "modern" casebook on labor law,[77] a work of over 1400 pages, which one reviewer found "alarming" but overall concluded "the selection of material is excellent."[78] [i] The casebook was the first to emphasize (almost exclusively) the collective bargaining agreement, which the Wagner Act had put at the center of industrial relations. Before Cox's text such courses mainly dwelt on industrial warfare.[79]

Cox began his association at tis time with John T. Dunlop, a labor economist who had joined the Harvard faculty a year before Cox. Their thinking would influence each other, and the two collaborated on two articles in the 1950s and would be involved in similar arbitrations (particularly in the construction industry). They would later also become involved in similar federal wage mediation efforts. The two (Cox in law and Dunlop in economics) would become the most important influences in the developing legal model for industrial relations, which detractors from the later critical legal studies movement labelled "industrial pluralism"—a model "promoted the polices of free collective bargaining, responsible unionism, limited worker participation in management, and a restricted right to strike. Industrial pluralists regarded the state as a neutral party that treats organized labor fairly if it functions within this framework."[80] Cox's role in developing this view went beyond academic writing, and included his role in various government agencies, his participation in panels and symposia, his work in professional associations, his recommendations and advice to policy-makers and, of course, through his students. Cox would also occasionally draft bills, such as he did for three Massachusetts Republican state legislators who were seeking to broker a compromise between the AFL-CIO anti-injunction bill and the Republicans' refusal to modify the state courts' practice of issuing injunctions, without notice or hearing, in a host of labor disputes as well as recognition and union security cases.[81]

Wage controller and foremost academic expert in labor law[edit]

Wage controller[edit]

Cox's experience as an arbitrator, his collaboration with Dunlop and others in conceiving a labor policy built around collective solutions, and his own belief in the power of reason and good faith led him to conclude that optimal results for workers and industry could be achieved without coercion by either side. And when there was a government interest involved, he firmly believed in the ability of the New Deal-type tripartite boards to reach the optimal results for the private parties and the public, even despite his own experience at the NDMB. He was so certain of its usefulness he was willing to recommend it even during peacetime.

In 1947 most foreign policy liberals believed that a massive recovery program for European democracies was necessary to prevent their succumbing to Soviet aggression or to subversion by totalitarian ideology. In response to an urgent plea by Columbia scholars,[j] Congress authorized interim relief. But there was fear that the level of assistance needed would put intolerable inflationary pressure on the U.S. economy. It was the Harvard faculty this time that provided the suggestion: an allocation program to moderate demand, restricting credit and if necessary price controls. Wage policy was not specifically enumerated but Cox's name on the list made clear that that would be part of the "aggressive anti-inflationary measures" that might be resorted to.[k] That spring aid relief began under the Marshall Plan but no mechanism to intervene with the economy, especially wages, was introduced to replace the National Wage Stabilization Board, which had expired in 1947.

Within two years, however, full mobilization for war brought the wage machineries back with the War Stabilization Board and its related programs.[l] Harvard Law School had readied itself from the start, sponsoring a program for practicing lawyers on legal aspects of mobilization at which Cox and Dunlop spoke on wage stabilization and industrial dispute resolution.[84] Both were called to sit on boards. From 1951-52 Cox served (without compensation) as co-chairman of the Construction Industry Stabilization Commission, a board that dealt with wages in an industry with special labor issues.[85] [m]

The wage control scheme came apart with the steel strike in 1952. Anxious to maintain production, Truman seized the steel industry without Congressional authority. When the move was struck down by the Supreme Court,[87] Congress replaced the board with one in which, because it was stripped of power to set wages, both the C.I.O. and A.F.L. agreed to participate.[88] Truman, using recess appointment powers, appointed Cox to chair the new board.[89] Cox claimed that despite its limitations he was "determined to 'make it work.'"[90]

The trend of cases piling up to be resolved, however, disturbed Cox. He told a meeting of the American Bar Association's Labor Relations Section in San Francisco: "Every morning my breakfast is spoiled by reading bout another wage settlement calling for an increase whose approvability is doubtful under present stabilization policies."[91] [n] But in the first case he sat on, one involving a 10¢ per hour increase for 25,000 employees of North American Aviation, a major producer of military aircraft, even though the raise was 50% above the amount permissible under the previous boards policy.[92] After the decision the industry members met with Cox to tender their resignation. He pleaded with them not to dash the board, telling them that proposing a new higher wage rate, but one consistently held to, would best keep wages stabilized. They agreed to stay on.[93]

The case that would be the board's undoing involved the United Mine Workers, just like the case the brought down the NDMB. Shortly after Cox's speech to the ABA, the coal industry agreed with soft coal miners to a wage increase of $1.90 a day plus an increase in benefits.[o]

It became clear that John L. Lewis, once again, had his members ready to defend every bit of their gain. When one company refused to include the increase in miners' pay until the stabilization board had approved the agreement, 700 miners walked out of the mine in Harrisburg, Illinois, and there was fear that a "silent strike" would spread among the 375,000 soft coal miners in the U.S.[98] Although Cox promised prompt review of the wage increase, a week later, when the strike had spread to 117,500 miners, Cox planned to announce a one-week postponement of the vote at the suggestion of the board's director Roger L. Putnam, but the labor representatives refused and Cox cancelled the announcement.[99] On the last day to decide, October 18, 1952, the Board disallowed anything above a $1.50 a day increase. Announcing the decision Cox said: "A wage stabilization program under which an excuse was found for approving every increase requested by a powerful group would be a fraud."[100] The coal miners walked off their jobs, while Lewis assailed the board: "Four agents of the National Association of Manufacturers, aided by a professor from the Harvard Law School and his timid trio of dilettante associates, form a cabal to steal 40 cents a day from each mineworker."[96] The President first intervened to resolve the walkout, and then after Putnam affirmed the board's decision, on December 3, reversed it and reinstated the pay raise.[101] Despite the advice of Dunlop and another friend,[p] Cox resigned the next day.[103] Some colleagues saw this as an unnecessary act of "grandstanding" and a disservice to the President, particularly as he made it a very public show of "principle" instead of quietly resigning[104] and also because it set off a chain reaction with industry members resigning, the Chamber of Commerce refusing to replace them and finally the resignation in frustration of Putnam himself.[105] [q]

The few months he spent in Washington would tarnish his reputation for many years with conservatives constantly recalling that he was a "wage-price controller"[107] and liberals who saw him as "vain, easily offended and highly principled."[108] Cox returned to Harvard thinking he would never participate in national government again.[109]

The 1950s at Harvard[edit]

On his return to Cambridge there were rumors that Cox might succeed James Bryant Conant as President of Harvard University.[110] The position in stead going to Nathan Pusey, Cox went back to a career consisting of three parts: teaching, professional associations and arbitrations, and scholarly writing.

As a teacher Cox was considered expert in his fields but as a teacher humorless, distant, rigid and eccentric Despite his reputation for aloofness, he volunteered time to help revise student law review notes, judge moot court and appellate advocacy competitions and provide career advice.[111] He also taught labor regulations to selected labor leaders as part of Harvard's "Trade Union Program."[112]

To make time for professional activities, Cox scheduled his classes for the beginning of the week.[113] Out-of-town lectures, bar committee meetings, arbitrations and related work could be done at the end of the week. Cox was elected chairman of the State Legislation committee of the ABA's Labor Relations Law Section (1948–49) and then secretary of Section (1954–58).[114] He drafted legislation for state legislatures on a non-partisan basis.[115] [r] In 1958 he was made a member of the advisory committee of the Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts.[117] He continued sitting on arbitration and other panels. One novel panel was one established in Philadelphia by the Upholsterers' International Union providing for an outside group to police union discipline. Cox was named chairman of the panel.[118] [s] Among the major arbitrations Cox sat on were the two major railroad arbitrations involving the engineers in 1954 and 1960, in which he and Princeton economist Richard A. Lester were the two neutral members.[121] In New England he arbitrated disputes between unions and management in the textile and machine tools industries.[122]

It was with his academic writing and bar association work, however, that Cox became immensely influential in the labor field. His writing was so prolific that Dean Groswold pointed to Cox when he needed an exampe of the kind of academic output he was seeking from the faculty.[123] Given that the peak of his academic career also coincided with the enactment of the statutes that defined industrial relations, his work, usually the first on any new topic, shaped the Court's thinking. His one-time student and later colleague Derek Bok described this influence:

In the 1950s, the National Labor Relations Act was still relatively new, and the Taft-Hartley Act was in its infancy. Over the decade, the Supreme Court had a series of opportunities to clarify the meaning on, the legal status of arbitration, and other important issues of policy left open by Congress. In case after case, when the majority reached the critical point of decision, the justices would rely on one of Archie’s articles.[124]

In addition to his direct effect on Supreme Court decisions,[125] Cox's scholarly writing influenced other academics and practitioners who widely cited him. The Journal of Legal Studies lists Cox as one of the most-cited legal scholars of the twentieth century.[126] The framework he developed, first in the two articles with Dunlop in 1950-51, then elaborated on his own, became the standard view of the Wagner and Taft-Hartley Acts. It assumed roughly equal bargaining power between union and management and interpreted the labor laws (often contrary to the language of the statutes themselves) to limit individual employee rights unless pursued by his bargaining agent, to restrict the subjects on which management is required to bargain about based on past practices, to permit unions to waive rights the statutes otherwise gave to employees and in general to advocate the notion that labor statutes should be interpreted to promote industrial peace over enhancing the economic power of labor.[127] The framework remained the dominant view of federal labor relations until the late 1950s when concerns over member participation began to shape policy.[128] It would be Cox and his work with Senator Kennedy on the bill that became the Landrum-Griffin Act that would begin the new framework.

Advisor to Senator Kennedy and Role in the Kennedy Administration[edit]

Kennedy advisor, then partisan[edit]

Kennedy's labor expert[edit]

When John F. Kennedy first began serving in the U.S. Senate, he had political ambitions and knew that he needed to build his political resume to fulfill them. He decided that labor issues would be one area where he would specialize. So he wrote to Cox in March 1953 inviting him to testify before the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare.[129] Cox was a natural ally to seek out. He was one of Kennedy's constituents and a fellow Harvard alumnus. More importantly he was a nationally-recognized academic expert on labor law and a liberal Democrat[t] with a predisposition towards labor. Kennedy testified on April 30 on various possible amendments to the Taft-Hartley Act relating to state-federal jurisdiction and secondary boycotts. The two had lunch afterwards and nothing came of the bills.[131]

Four years later Kennedy became a member of the McClellan Committee whose hearings on labor corruption began revealing unsavory practices. The volatile televised hearings provided a high risk (in terms of labor support), high reward (in terms of public exposure) that required political finesse based on substantive knowledge. What shown the spotlight more intently on Kennedy was that his brother was the chief counsel of the committee and his wrestling matches with Teamsters leader Jimmy Hoffa during his examination were riveting. Kennedy himself had become chairman of the Subcommittee on Labor, and so he wrote Cox in April 1957 requesting that he put together an informal group of academic experts to advise him on specific labor reforms.[132] The group of labor academics selected by Cox,[u] which was restricted to considering issues of internal union management and addressing abuses uncovered by the McClellan Committee, met through the fall and winter of 1957 and delivered in December to Kennedy a written report to Kennedy dealing with trusteeships, union memberships, expulsions and union elections.[134] The efforts of the group proved useful to Kennedy aside from legislation; Kennedy was able to milk good publicity from his "brain trust" with only vague hints at what he proposed to do.[v] As for legislation, Kennedy asked Cox to draft the bill. Cox did so himself and sent it in January 1958.[136] Against the advice of Cox (who knew Kennedy was unprepared from the brusk style of labor heads), Kennedy decided to show the proposed bill to labor leaders (whom Cox referred to with the somewhat derogatory term "labor skates"[137] [w]) including George Meany and A.J. Hayes. As Cox put it they "gave him a very rough time."[139][x] At the committee hearings Meany gave "very hostile, very hard-nosed" testimony. When Kennedy tried to assure him that the legislation was produced by academics who were friends of labor, Meany replied: "God save us from our friends."[142][y]

Stewart McClure, clerk of the committee, said that the Republicans hated Cox. His coaching of Kennedy had allowed Kennedy to parry all questions and treat difficult points with "the precision of a trained surgeon."[145]

With Republican co-sponsor Irving Ives, whose consent to lend his support was finessed,[146] the bill became known as the Kennedy-Ives bill. Cox spent much time in Washington in the first half of 1958 advising Kennedy, dealing with union representatives and second-chairing Kennedy at private meetings with legislators. When the bill reached the floor of the Senate, it passed 88-1. The editorial board of the New York Times called the bill "a triumph of moderation and a powerful blend of principle and political savvy." In particular it praised the policy approach of the Committee Report (largely designed by Cox), which sought to ensure against corruption while at the same time showing care "neither to undermine self-government within the labor nor to weaken unions in in their role as bargaining representatives of employe[e]s."[147] But, as the Times had warned, the bill was sent to its political graveyard in the House when the Eisenhower Administration, thinking that tougher measures on unions were needed, cobbled together a coalition which included Southern Democrats and defeated it.[148]

Kennedy reintroduced his bill (this time with Senator Ervin as co-sponsor) in the 1959 session. This time labor over-played its hand, and believing that the November 1958 elections had given them a favorable vote in the House, they demanded "sweeteners" in the way of amendments to the Taft-Hartley Act.[z] Cox urged that the issue of union anti-corruption measured be kept separate from question of permitted labor practices, and on this Kennedy was sympathetic. But the union leaders wanted a "price" for their support. Kennedy responded by obtaining approval for a Blue Ribbon commission to study the issues; Cox was named chairman and the commission included Arthur Goldberg, David L. Cole, Guy Farmer and W. Willard Wirtz. In the end, Kennedy accepted labor's "sweeteners," and Ervin took his name off the bill. At the same time, Senator McClellan proposed a labor "Bill of Rights" which would have expanded drastically federal intervention into internal union affairs. Kennedy and Cox were able to draft a substitute which watered down the more anti-union provisions. Cox took the new version to McClellan's counsel, Robert F. Kennedy, who, much to Cox's surprise objected to them. Cox concluded that Robert Kennedy lacked sympathy with and even an understanding of organized labor. It was the beginning of the strain between Cox and Robert Kennedy. Senator Kennedy simply ignored his brother's objections. Having worked diligently to accommodate all positions, Kennedy sent the revised bill (without McClellan's "Bill of Rights") to the Senate floor where it passed in April 1958, by a vote of 90-1.[150]

In the meantime, the Eisenhower Administration and business lobbyists were using the lurid details uncovered in the McClellan Hearings to pressure conservative, Southern Democrats and Republicans to come up with bills not only regulating union internal affairs but also cutting back on permitted union activities and bargaining power. The bill the House passed was the one sponsored by Georgia Democrat Phillip Landrum and Michigan Republican Robert Griffin.[aa] In addition to imposing more extensive regulation of internal union affairs, it provided for amendments to the Wagner Act prohibiting certain union activities, such as certain secondary boycotts and certain picketing in connection with organizing activities, eliminated "hot cargo" agreements (in which prohibited employers from dealing with companies with labor disputes) and gave over to the states jurisdiction over matters, on which the NLRB declined to exercise its jurisdiction. The bill passed by a vote of 303-125, stunning labor officials because it was substantially more anti-union than anything the Senate contemplated, including Kennedy's bill from 1957 and because they badly misjudged the results of the 1958 election. Their only hope was in Kennedy's ability to salvage what he could in the meeting between the chambers to reconcile the two bills. Kennedy chaired that meeting and brought along Cox as his chief aide.

Cox was "surprised" at the rough and tumble of the conference committee.[153] Senator Dirksen tried to bar him altogether as "having no business here."[149] Then on at least two occasions Cox was personally insulted in a way that was wholly outside his experience. Conservative North Carolina congressman Graham Arthur Barden Complained that he was tired of "these intellectuals nitpicking … ." Landrum in a fit of pique pointed at Cox and called him a "Communist." In both cases Kennedy struck back, telling Barden that he was "sick and tired of sitting here and having to defend my aide time and time again …" and as to Landrum, his "Irish temper" (as Cox called it) was so in display and the dressing down he administered to Landrum was so severe that the meeting had to be adjourned to let the sides cool down.[154] In the end, after extended grueling negotiations, a bill was finally agreed to, and it became the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act. It was substantially more anti-union than the Senate bill, but Kennedy’s less onerous provisions governing internal union affairs prevailed. The prohibitions on union activity from the Landrum-Griffin bill remained, but Kennedy saved the Taft-Hartley "sweeteners." All in all, years later Cox concluded that "there were things that would have been better, but it came out not too bad."[155] For his part, Kennedy did not try to have his name put on the result, and it became known as the Landrum-Griffin Act.[156][ab] Nevertheless, it showed that Kennedy could maneuver a complex piece of legislation from beginning to end, an important part of his resume for the quest for the nomination next year. Cox later noted: "this was his one big thing legislatively."[158] The worry was that despite the effort, it might lose him labor support.[ac] And while this bill remained his one legislative achievement, Cox would later find out that he really did not have "any interest in labor at all. I don’t think it aroused his interest."[159] For his part Cox left with unpleasant conclusions about the process: "After living most of one's life in a relatively rational community, watching the House of Representatives at work is one of the most disheartening sights in the world."[149]

Head of the Kennedy campaign's "Brain Trust"[edit]

In the fall of 1959, after the work on the Landrum-Griffin Act had wound up, Kennedy confided to Cox the open secret that he was running for president.[160] In January 1960 he wrote Cox formally asking him to head up his efforts to "tap intellectual talent in the Cambridge area" and then "ride herd over twenty or thirty college professors" in their activities for him.[ad] Cox brought a number of eminent policy experts in a number of fields into contact with Kennedy. Although many were skeptical of his candidacy (and some had been loyal to or inclined towards either Adlai Stevenson or Hubert Humphrey, Kennedy won them over at a meeting in Boston's Harvard Club on January 24.[165] [ae] In the period leading up to the Democratic Convention in July Cox acted mainly as a "stimulator" to prod various academics to send memoranda to Kennedy or to find academics to supply Kennedy with policy positions on specific topics.[167] While before the Convention Cox had not recruited extensively beyond the Boston area, he had at least one recruit from the University of Colorado and he got academics at Stanford.[168] Even though the number was not large before the nomination, no other Democratic contender, not even Stevenson had made an effort to recruit intellectual partisans.[169]

As with the case of Cox's informal group of labor advisors, Kennedy was anxious to use Cox's contacts not only for their expertise but also for the éclat they gave his campaign. A Congressional Quarterly article in April, widely reprinted in local papers, named Cox and the other Cambridge advisors as a key to the kinds of policies Kennedy would advocate.[170] "Of John F. Kennedy's political talents none has been more helpful to him than his ability to attract capable men to his cause," the Times said in the middle of the Convention.[171] The description of Cox's academic advisers was designed to recall Roosevelt's "Brain Trusts": "More ideas poured in from Cambridge, Mass., where an astounding galaxy of scholars had made themselves and informal brain-trust for Senator Kennedy."

After the Los Angeles Convention Kennedy, now the nominee, asked Cox to move to Washington to have an expanded role, hiring speechwriters and coordinate academic talent. Cox accepted, and then Kennedy point blank asked Cox if he thought he could get along with Ted Sorensen and explained "Sorensen’s fear that somebody was going to elbow his way in between him and Kennedy."[172] Cox assumed he could.[173] Cox had been unaware that Sorensen had already been at work, back in February, trying to compartmentalize and minimize Cox's groups' efforts. He told Joseph Loftus of the Times that the Cambridge group was "something 'much more talked about than fact.'"[174] Cox would soon discover, however, that Sorensen always "was terribly worried about being cut out" and protected Kennedy from independent advice including Cox's.[175]

Cox set up office in Washington, D.C., hired other speech writers and solicited research from academics. Cox soon found that the speeches his group wrote were not used in campaign events. Cox much later recognized that his manner of speech-writing was "even in 1960, old-fashioned," filled as they were with statistics and Roosevelt-style detailed explanations of policy.[176] Cox wrote to Sorensen (who travelled with Kennedy) seeking a delineation of roles, but was never satisfied. Cox tried to force a showdown by flying to meet Sorensen and Kennedy in Minneapolis on October 1. In the campaign plane Sorensen loudly dressed down Cox, telling him his written speeches were inadequate for campaign events.[177] On October 11, Kennedy told Schlesinger that he was aware of and regretted the tension between Sorensen and Cox, but said that Sorensen was "indispensable" to him. In view of Sorensen's posssessiveness he even suggested that Schlesinger avoid Sorensen and communicate with him through Jackie.[178] Cox spent the last month of the campaign in Washington in low spirits. Before he left Washington, just before election day, Kennedy suggested that Cox might be helpful during the transition (if Kennedy won). Cox replied in a non-committal "sour" way, summing up his disappointment with his role in the campaign.[179]

Despite Cox's disappointment, the work of the speech-writing unit proved vital to Sorensen and Dick Goodwin by providing them with much of the content, factual support and occasional turn of phrase of their stump speeches on the campaign trail.[af] Cox's group, together with Robert Kennedy and Myer Feldman, who headed Kennedy's opposition research, also issued nearly daily statements to the press, independent of the canddate who was on th eroad.[182] Moreover, research that flowed through Cox to the campaign provided the beginnings of opinion sampling that informed the candidate's approach to audiences.[183] Nevertheless, Cox's response to Kennedy ended any chance he would participate in the transition.

Solicitor General of the United States[edit]

Despite publicly denying that he was considered for public office,[184] Cox worried he would be offered a seat on the NLRB or a second echelon position in the Department of Labor. Neither position offered new challenges for him, but he worried about the propriety of refusing.[185] Before leaving for his family Christmas celebration in Windsor, he was tipped by Anthony Lewis of the Times that he had been chosen for Solicitor General. He decided that if he were offered the post, he would tell the president-elect that he would think the matter over. But when Kennedy called, interrupting a Christmas lunch, he accepted on the phone.[186] Cox was unaware until much later that his law school colleague, Paul Freund, whom he had recommended for the job, declined and recommended Cox in turn.[187] Next month arriving for confirmation hearings, Cox's reputation on the Hill was such the hearing took only 10 minutes; even minority leader Dirksen, who knew Cox from Landrum-Griffin days, said he "had been quite impressed with his legal abilities … ."[188]

In the nearly century that the office had existed before Cox occupied it, the solicitor general, as the government's lawyer before the Supreme Court, was immensely influential. Cox held the position at a time when the Warren Court was about to involve the Court in issues never before considered appropriate for judicial review, at a time when the country was ready for the Court to decide various questions of social justice and individual rights. Cox was aware of the pivotal time the Court and he faced and explained it in an address right before the beginning of the first full Term he would argue in:

[A]n extraordinarily large proportion of the most fundamental issues of our times ultimately go before the Supreme Court for judicial determination. They are the issues upon which the community, consciously or unconsciously, is most deeply divided. They arouse the deepest emotions. Their resolution—one way or the other often writes our future history. … Perhaps it is an exaggeration to suggest that in the United States we have developed an extraordinary facility for casting social, economic, philosophical and political questions in the form of actions at law and suits in equity, and then turning around and having the courts decide them upon social, economic, and philosophical grounds. It is plainly true that we put upon the Supreme Court the burden of deciding cases which would never come before the judicial branch in any other country.[189]

Cox began his Supreme Court advocacy by choosing a case that would announce the new emphasis to be placed on civil rights.

Civil rights and sit-in cases[edit]

During the customary introduction of the Solicitor General to the members of the Court, Justice Frankfurter had an extended talk with his former student. The justice advised Cox that the first case to argue should be something involving criminal law. Cox gave due weight to the recommendation, but he met vigorous objections from his assistant Oscar Davis who argued that civil rights was the most important legal issue facing the country and that Cox should signal the new administration's commitment to fight for it in his first case. Cox agreed and selected Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority.[190] The case, brought by an African-American who was barred from a private restaurant renting from a building owned by the state of Delaware, confronted the Court squarely with the limitations on Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of "equal protection of the laws" erected by the so-called Civil Rights Cases of 1883 which held that the constitutional guarantee only applied against "state action."[191] Cox persuaded the Court that the fact that the business was a state lessee as well as franchisee, was located in a parking complex developed by the state to promote business, and, a piece of "evidence" asserted by Cox from his own visit to the scene, that the complex flew a Delaware flag in front of the building all rendered the state a "joint participant" with the restaurant, sufficient to invoke the Fourteenth Amendment.[192] The case was at the beginning of the Court's dilution of the "state action" requirement in racial discrimination cases.[193]

By May 1961, the civil rights movement, led by James Farmer of CORE initiated what would become a wave of non-violent confrontations against discrimination in public transit and other accommodations. The Attorney General's Office under the active supervision of Robert Kennedy took active measures to protect the protestors in the face of local political and police indifference or active complicity with violent resisters.[194] Cox was regularly involved meetings over day-to-day Justice Department activities in addition to preparing to overturn state court convictions of civil rights protestors (under various vagrancy, trespass and even parading without permit statutes). Cox came into close contact with Robert Kennedy, and while the two had widely different styles (Kennedy was impulsive and somewhat cavalier of legal principles; Cox was cautious against making missteps that would set the movement back or commit the Court to a position which might lose it legitimacy), Cox grew to admire Kennedy.[195] Impatient of a piecemeal approach, Robert Kennedy, but more importantly the civil rights community, particularly Jack Greenberg of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, sought near elimination of the "state action" doctrine, arguing that restaurants were like "common carriers" subject to the Fourteen Amendment or that the act of enforcing a trespass law used to further private discrimination was itself sufficient "state action."[ag] Cox did not believe the Court would make so radical a break with eighty-year-old precedent. So each case he argued on narrow grounds which did not require the Court to overrule the Civil Rights Cases, and each case he won on those grounds, in the process infuriating Jack Greenberg who was arguing in those very cases for the broader approach.[197] The cautious approach, however, garnered Cox much credibility with the Court, which came to realize that he was not going to lead them into areas with uncertain future consequences.[198] After a number of these cases, however, even the Court requested briefing on the "state action" doctrine in Bell v. Maryland in 1962. Cox took a slightly more advanced position arguing that where trespass laws were used to prosecute civil rights demonstrators in states such as Maryland where there was a history of racial segregation by custom and law, then the discrimination was part of the enforcement sufficient to invoke state action. Although even this position disappointed civil rights activists and the Justice Department, it prevailed, but in the face of three dissents (including that of Justice Black), suggesting that a broader rule might have been rejected by a majority.[199]

Reapportionment cases[edit]

The cases that troubled Cox the most during his tenure, and the area where he differed widest from Robert Kennedy involved malapportionment of voting districts. Pver the years failure to re-allocate voting districts particularly in state legislatures, produced wildly disproportionate districts, with rural areas having many fewer voters than urban districts as a result of the urbanization of America.[ah] The result was dilution of the urban vote with policy resulting accordingly; rectification would benefit Democrats politically.[201] The problem was that Justice Frankfurter had held in a plurality decision in 1946 that such issues amounted to a political question—a matter not appropriate for the Court to resolve.[ai] But a case surfaced from Tennessee which seemed ideal to test that ruling. Tennessee had not reapportioned its legislature since 1910 and, as a result, there were urban districts that had eleven times the citizens of rural districts. Cox decided to submit an amicus curiae brief supporting the plaintiffs in Baker v. Carr. The case was argued once in April 1961 and re-argued in October. In between, Cox was subjected to an unpleasant onslaught by Frankfurter at a public dinner and relentless questions in the October argument.[202] When the decision was announced, however, Frankfurter was joined by only Harlan, the result was 6-2.[203] The first case proved far easier than he expected. The holding was relatively narrow, simply providing federal court jurisdiction, and followed the points in Cox's brief.[204] But Cox had much more difficulty with the follow up cases, because he could not persuade himself that history or legal theory would demand a one-man-one-vote standard in all cases. He developed what he later called a "highly complex set of criteria," but in the end when the Court finally erected the one-man-one-vote standard it simply made the general rule subject to all the exceptions that Cox had tried to weave into his proposed standards. As Chief Justice Warren's clerk later told him "all the Chief did was take your brief and turn it upside down and write exceptions to the one-person one-vote that covered all the cases that you had attempted to exclude by this complicated formula."[205]

Politics, justice and law[edit]

In 1962 the Court would change when two vacancies occurred, involving the seats of tow conservative judges, both evidently victims of Baker v. Carr. Shortly after learning the result of that case in March 1962, Cox was advised that Justice Charles Evans Whittaker announced his resignation. Cox wrote a letter of regret. The judge promptly phoned Cox, invited him to his chambers and advised him that the agony of deciding the first reapportionment case "just about killed me."[206][aj] The next month Justice Frankfurter had a stroke. When Cox visited him, after his retirement in August, Frankfurter "murmured—he couldn’t speak altogether clearly, but he had murmured something that seemed to say it was the government’s position, my argument in Baker and Carr, that brought on his first stroke and led to his forced retirement."[208][ak] Whatever the cause, the President had two vacancies to fill, and Cox was at least a logical candidate.[al] Cox's name was on the short list for the first vacancy,[am] but Kennedy wanted to get ahead of the momentum for a conservative pick that Southern Democrats mounted and promptly selected Deputy Attorney General Byron White, largely on the ground that he was not a narrow Harvard academic, which Kennedy felt had characterized too many of his recent appointments.[211] As for the later choice, the President initially proposed Freund to replace Frankfurter, but Robert Kennedy argued that Freund had refused the appointment that Cox took and since Cox "had done a fine job" he deserved the appointment more than Freund. In the end the President felt constrained to appoint a Jew to the "Brandeis-Frankfurter" seat, and appointed Arthur Goldberg.[212] As for Freund and Cox, the President told Schlesinger: "I think we'll have time for everybody."[213] Shortly after White had been appointed, Cox attended a dinner at which retired Justice Stanley Reed told Phyllis: "Too bad Archie will never become a justice, … It’s like a pendulum; it swings back and forth. If it swings out and hits you when it swings in your direction, then you are named to the Court. If it swings in your direction, but doesn’t get there, it never swings further on a later occasion, so you never get it." Cox said taking this to heart saved him much "hoping and anguishing."[214]

Archibald Cox was the only person in the Justice Department who had a personal relationship with the President (other than his brother the Attorney General). Kennedy occasionally used the relationship to engage Cox directly on legal issues of interest to him. Among such issues were legal issues in legislation providing for low interest loans for construction of religious schools,[215] wage and price controls during the steel price increase in 1962,[an] research in connection with the interference of government officials with the admission of James Meredith into University of Mississippi[ao] and resolution of the "mudlumps" issue between the federal government and Mississippi.[ap] Robert Kennedy frequently told the story of the time the President called to ask for a legal opinion. The Attorney General said he would get right on it, but the President replied: "I said I wanted a legal opinion … Get Archie Cox on it."[221]

The relationship between Cox and Robert Kennedy grew close over time. Cox, like many others, believed that Robert, who graduated in the middle of his class at Virginia Law School and had never practiced at all, had insufficient qualifications for the office. Cox's qualms went further back, to the time of his support for the McClellan "bill of rights" for union members. But with time he grew to trust and admire Robert. Robert for his part always remained respectful and deferential to Cox on matters of law. He never ordered Cox to take a position before the Supreme Court, but often would subtly "lobby" him. By calling repeated meetings where Justice staff could air their opinions, he pushed Cox towards the one-man-one-vote position in the reapportionment cases, for example. Kennedy never convinced Cox to ask the Court to overrule the Civil Rights Cases and the doctrine of state action,[aq] but circumstances moved the President and Attorney General to seek a legislative solution.

1963 was a time of increasing violence in the South against African-Americans, as segregationists mounted ever more dogged resistance.[ar] The Administration decided to turn from its policy of relying on individual voting rights and desegregation lawsuits accompanied by executive orders and appointments[224] to a push for civil rights legislation. On February 28, Kennedy proposed his first civil rights bill which included "timid measures" to secure voting rights. Southern Democrats filibustered the bill in the Senate.[225] After Governor Wallace's attempt to prevent integration of the University of Alabama by standing in the schoolhouse door on June 11,[226] Kennedy made civil rights a moral crusade and had legislation ready to introduce in the House by June 19. A central provision was public accommodations. The President and the Attorney General closely managed the bill.[227] Cox had no role in drafting the legislation, but supported it publicly. On November 20, Cox attended the Justice Department birthday party for Robert Kennedy. During the celebration the Attorney General made a long self-deprecating speech about all the problems he had "solved." Cox told Ramsey Clark that he thought it signaled Kennedy's decision to leave the department (from exhaustion and disillusionment) and predicted he would be gone by the next month.[228] Two days later the President was assassinated in Dallas.

Under the new President[edit]

Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach took over for the grief-stricken Attorney General. The first request of the acting Attorney General was that Cox accompany him to see the Chief Justice and request him to head a commission to investigate the circumstances surrounding the assassination of President Kennedy. Cox was reluctant, believing that Warren should refuse the request, because it would have adverse impact on the Court. He agreed but asked that Katzenbach not have him try to persuade the Chief Jusitce. In the end Warren declined the request, and the two Justice employees left.[229] Within an hour the President called and requested him to meet. Warren capitulated. He said in 1969 that because of it, it became "the unhappiest year of my life."[230]

The civil rights legislation which Kennedy was unable to see pass during his lifetime received the needed momentum from his death and the legislative skill of President Johnson. In 1964 the public accommodations bill passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The obvious constitutional attack on the legislation was its constitutionality under the Fourteenth Amendment because it sought to regulate conduct which was not "state action." Cox and Assistant Attorney General and Head of the Civil Rights Division Burke Marshall, however founded the legislation on Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce. Although both John and Robert Kennedy questioned the optics of using the Commerce Clause, they did not object.[231] Cox had no difficulty having the Court uphold the statute on that basis when he argued the cases in October.[as]

After a landslide election victory, Johnson used his State of the Union address in January 1965 to, among other things, promise a voting rights act.[232] It was Cox who developed the first draft. The mechanism devised by Cox was to provide for a presumption of illegality of a list of practices including literacy tests and similar devices if the state had a history of low minority voter turn-out as shown by voter statistics. In such cases the burden was shifted to the state to prove nondiscriminatory intent. This mechanism remained the heart of the legislation throughout the legislative process. Both Ramsey Clark and Nicholas Katzenbach admired the mechanism for its legal craftsmanship and statecraft (because it avoided the need to prove intent to discriminate).[233] Before the bill was submitted to Congress Cox answered a question in Court which was used by nationally syndicated columnist Drew Pearson to embarrass Cox before the new President. On January 28, Cox urged the Supreme Court to reverse a lower court decision which held that the federal government had no power to sue a state alleging violation of the Fifteenth Amend by discriminatory devices aimed at African-Americans. Cox argued the narrow ground that the government had such power. When the Court expressly asked Cox whether he was asking the Court to strike down the statutes, Cox answered that he was not, only that the case be remanded to the three-court panel. The Court's opinion, delivered on March 8, highlighted this exchange in such a way that some inferred that Cox passed up a golden opportunity.[at] Pearson's column stated that Cox had cost the civil rights movement two years in litigation, and for that he point blank suggested that Johnson replace Cox as solicitor general.[234]

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 mooted that case, and Cox would go on to defend the legislation successfully before the Court,[235] but he did so as a private attorney.[au] In the summer after Johnson's victory Cox offered his resignation in order that Johnson might pick his own Solicitor General if he chose. Although Cox dearly loved the job,[av] he overrode Katzenbach's strong objections. Johnson accepted the resignation on June 25, 1965.[237]

Return to Harvard[edit]

In 1965, Cox returned to Harvard Law School as a visiting professor, teaching a course in current constitutional law and a section in criminal law.[238] He was soon named the first recipient of the Samuel Williston chair.[239] Although he would occasionally write on labor law, his interest now seemed constitutional law and the role of law in society. Many on the left, however, saw his approach to the Constitution as narrowly legalistic, temOprizing and seen from the vantage of the privileged few. A paper he presented to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1965 was published in 1967 in a book with papers by Mark DeWolfe Howe and J.R. Wiggins called Civil Rights, the Constitution, and the Courts, consisting of papers delivered to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1965 and published in book form in 1967. Cox's contribution, "Direct Action, Civil Disobedience and the Constitution," argued that "direct action" in violation of a "plainly valid" law (as opposed to a plainly unconstitutional law) are impermissible.[aw] In the midst of anti-war, anti-Establishment, militant civil rights and other upheavals of the last 1960s Cox's proposition seemed naive, gradualist and out-of-touch. One reviewer called it "an anachronism even before its publication."[241] Consisting only of "pious wishes," said another.[ax] The conception of Cox as the ivory tower liberal. more concerned with the sanctity of the law than the concerns those oppressed was crystallized by Victor Navasky's 1971 Kennedy Justice, which was largely based on unnamed Justice Department lawyers and two institutional civil rights attorneys of a tentative, unsympathetic Cox requiring the constant nudging of Kennedy to make "grudging" and "inch-by-inch" movements away from his initially conservative positions in civil rights and reapportionment cases.[ay]

Neither a politician nor a bureaucratic infighter, Cox never responded to public criticism. He confined himself to teaching and hi outside, mostly pro bono activities. Shortly after leaving the government, he represented the plaintiff in Shapiro v. Thompson,[245] in which he persuaded the Court to strike down a Connecticut waiting period of one year before new residents could receive AFDC benefits as an undue burden on the "right to travel." He consulted with Robert Kennedy, now Senator from New York, on labor issues, particularly the New York transit strike of 1966. Cox had been proposed by Mayor John Lindsay as a member of a panel to mediate the dispute but the transit union objected to him (and nine others) on the ground that he had no experience in transit matters.[246] At the beginning of 1966 Cox was a member of an panel to mediate a dispute etween the NCAA and the AAU over control of amateur athletics in the United sStates.[247] Lindsay appointed Cox the head of a three-man fact-finding panel to investigate the background of the New York City teachers' demands.[248] The panel's work came to nothing" the teachers struck in violation of the Taylor Law, and Cox was stuck paying $1,000 to rent the hall which the city failed to reimburse.[122]

When it came to politics, Cox did not always side with Democrats. In 1966 he arranged a reception for Republican Lieutenant Governor Elliot Richardson at the Harvard Faculty Cub which resulted in a number of other prominent Kennedy aides from Harvard supporting his bid for state attorney general.[249] When it came to Robert Kennedy's bid for the Democratic nomination for President in 1968, however, Cox was an early and prominent supporter.[250]

Cox did not participate in Kennedy's primary campaign. Instead he found himself examining a real life instance of direct action against valid laws—the Columbia student uprising in April of 1968. Two and a half weeks after the students of Columbia occupied the buildings which housed the college administration and the office of the President (April 23) and a week and a half after the violent police response which ousted them (April 30), Cox was called by Columbia labor law professor Michael Sovern, a member of a self-selected ad hoc committee of faculty who, filling the vacuum created by the absence of president Grayson Kirk, intervened to calm the situation, requesting Cox to head a panel to investigate the causes of the upheaval.[251][az]

A month into the panel's work Cox learned that Senator Kennedy had been assassinated. He would travel to Washington to speak of his grief in front of his former colleagues at the Justice Department: "We walk down the corridors and nothing has changed, but inside our hearts there is an aching emptiness. Our leader is gone and nothing is the same," he said.[252]