New data out of the Kirby Institute shows that the rate of HIV transmission in Australia has fallen, returning to a downward trend that has been the norm for more than a decade. So why are the papers saying that HIV infections are ‘at an 20-year high‘?

As I have been arguing for several years (see this post from 2013 and this one from 2010) the use of raw diagnoses as the only measure of progress against HIV in Australia fails to take account of the reality that there are more people living with HIV every year. With a greater HIV-positive population, in any HIV prevention scenario a greater number of new diagnoses can be expected. Because this is the case, simply looking at the number of new diagnoses tends to mask the considerable success we have had in combating HIV.

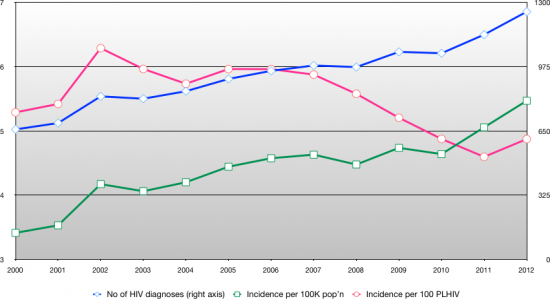

Here’s a graph that shows (in pink) the ‘HIV transmission rate’ (the number of new infections recorded per 100 people living with HIV) in Australia over the last 13 years:

The blue line shows the official HIV stats, and there’s no doubt they have trended upwards over the period. That’s nobody’s idea of good news, least of all mine. We want to turn that line around (and I think we will soon).

The pink line is my estimate of the HIV transmission rate. As you can see, it has actually fallen in nine out of the last 11 years and, despite a rise last year, it looks to be trending downwards. That is a good sign that, despite the rising population of PLHIV, the percentage of people who pass HIV on has been falling. That is a marker of success that is ignored by the official reports.

The use of the transmission rate as an alternative to the raw numbers isn’t just my idea: the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy uses it. The CDC uses it. Peer-reviewed epidemiological studies use it.

I am not suggesting we should ditch the reporting of the raw numbers – they are a useful and important measure. Governments and health economists care, as they should, about the numbers of people who will need medical care and support into the future. But they are less helpful when measuring the success of HIV prevention campaigns. A rise in infections doesn’t mean that prevention is failing unless the rise is greater than that which can be attributed to the increased PLHIV population. In fact, as the graph above shows, in most recent years the rise in infections is below that natural increase and that means we have had some measure of success – not that you’d know it from reading media reports or Kirby Institute press releases.

Stories headlined ‘HIV infections at a 20-year high’ suggest that, 20 years ago, things were better than they are now. They weren’t: people were dying in droves. The rate of HIV infections in 1994 was unnaturally low because a large proportion of PLHIV were seriously ill and dying. Suggesting that we have an alarming rise in new infections 20 years later, when we have twice as many people living with HIV and most of them are leading healthy, productive (and sexually active) lives is blinkered pessimism.

Disclaimer: as with my previous posts on this topic, I have to point out that I am neither an epidemiologist nor a statistician, and while my estimate is based on published data from the Kirby Institute, I don’t have access to the detailed data on which it is based.