Today, antifascist protesters converged upon Spring Street in Melbourne near the Parliament of Victoria. They went there to counter racist rallies being held by Reclaim Australia and the fascist United Patriots Front.

As usual Victoria Police was also in attendance, and in the days leading to the protest it had promised a large presence and random weapons checks in response to rumours of fascists bringing weapons and intending violence.

Victoria Police’s goal for the day was to facilitate Reclaim Australia and the United Patriots Front holding their rallies out the front of Parliament House. In order to achieve this mounted officers and members of the Public Order Response Team (PORT) complemented uniformed officers on the streets, and OC (Pepper) spray was deployed against counter-protesters.

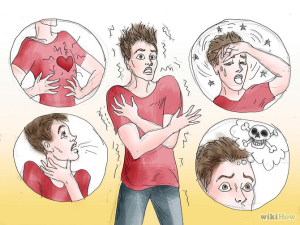

Amongst those affected by the OC Spray was a casualty who began to experience respiratory distress, a not uncommon side-effect of OC spray and other such “less-than-lethal” chemical weapons. In the course of attending to this casualty and decontaminating others who had been affected, members of the Melbourne Street Medic Collective (including one pregnant woman) were attacked by police with OC Spray and kettled in a small space at the top of Little Bourke Street.

Footage of the incident will be reviewed as it becomes available but at this point there seem to be only two explanations for the deployment of chemical weapons against the Street Medics: some witness reports have indicated that Victoria Police officers were spraying the crowd indiscriminately and did not check who they were attacking until after the fact. Others have said that police ignored the shouts of the crowd advising them that someone was receiving medical attention and with the decision to spray all medics this action should be seen as a deliberate attack upon medical personnel and their treatment space.

As one of our medics has since remarked:

“Possibly more than 100 people needed to be treated today as police indiscriminately fired pepper spray into the crowd, including onto an injured man who was struggling to breathe, was losing consciousness, and was awaiting an ambulance. They also sprayed the medics treating him. Someone had a seizure, two were taken to hospital and a few were sent home (by us as medics) due to the after-effects of the pepper spray (namely hypothermia-like symptoms of shaking and an inability to normalise body temperature). It was absolute fucking carnage and it was completely unnecessary and provocative. The racists didn’t cop any of the pepper spray at all as far as I know, and they got a three-line police escort away from the area.”

Victoria Police should rightfully be condemned for the deployment of chemical weapons, the targeting of medical personnel, casualties and medical treatment spaces with such weapons and, most of all, doing this in order to facilitate a public rally of racists and overt fascists and neo-nazis. Any assessment of the actions of antifascist protesters will conclude that they were inherently defensive: against threats of violence and the use of weapons by fascists and nazis as part of the United Patriots Front, and against the violence of racism and systematic oppression on the parts of Reclaim Australia, the United Patriots Front and Victoria Police.

The officers in command of PORT and of the event should immediately be suspended from their duties and investigations launched into how and why chemical weapons came to be used, and used against medics, injured persons and in treatment spaces. These investigations should be conducted with the possibility of demotion, termination from employment and/or laying of criminal charges (such as for assault) as outcomes.

Melbourne Street Medic Collective encourages all witnesses and concerned persons to lodge complaints with Victoria Police’s Conduct Unit and the Police Minister.

Police Conduct Unit

GPO Box 913

Melbourne VIC 3001

Telephone:1300 363 101

Email: “PSC-POLICECONDUCTUNITCOMPLAINTSANDCOMPLIMENTS@police.vic.gov.au”

| Role Occupant | The Hon Wade Noonan MP |

|---|---|

| Phone | 03 8684 0900 |

| Email Address | wade.noonan@parliament.vic.gov.au |

| Portfolio | Minister for Corrections Minister for Police |

Legal Aid Victoria has additional information on lodging complaints with police well worth a read.