- published: 15 Jan 2016

- views: 77398

-

remove the playlistSpread Of Islam

- remove the playlistSpread Of Islam

- published: 14 Jul 2015

- views: 1260725

- published: 19 Apr 2012

- views: 3275822

- published: 26 Mar 2015

- views: 14959

- published: 20 Jun 2010

- views: 7634

- published: 05 Jan 2014

- views: 258769

- published: 10 May 2012

- views: 1479895

The Spread of Islam began when Muhammad (570 - 632) began publicly preaching that he had received revelations from and was the last prophet of, God (Allah) at the age of 43 in 613 CE. During his lifetime the Muslim ummah was established in Arabia by way of their conversion or allegiance to Islam. In the first centuries conversion to Islam followed the rapid growth of the Muslim world created by the conquests of the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphs.

Muslim dynasties were soon established and subsequent empires such as those of the Abbasids, Fatimids, Ajuuraan, Adal, Warsangali in Somalia, Almoravids, Seljuk Turks, Mughals in India and Safavids in Persia and Ottomans were among the largest and most powerful in the world. The people of the Islamic world created numerous sophisticated centers of culture and science with far-reaching mercantile networks, travelers, scientists, hunters, mathematicians, doctors and philosophers, all of whom contributed to the Golden Age of Islam.

The activities of this quasi-political community of believers and nations, or ummah, resulted in the spread of Islam over the centuries, spreading outwards from Mecca to the Atlantic Ocean in the west and the Pacific Ocean on the east. As of October 2009, there were 1.571 billion Muslims, making Islam the second-largest religion in the world.

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

- Loading...

-

19:08

19:08The Untold History - How Islam Spread

The Untold History - How Islam SpreadThe Untold History - How Islam Spread

► Support the Series: https://www.gofundme.com/untoldhistory ► Subscribe Now: https://goo.gl/2tmfa8 Official Website: http://www.themercifulservant.com MS Official Channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/TheMercifulServant MercifulServant FB: https://www.facebook.com/MercifulServantHD My Personal Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mercifulservant MS Twitter: https://twitter.com/MercifulServnt MS Instagram: http://instagram.com/mercifulservant MS SoundCloud: http://www.soundcloud.com/mercifulservant PLEASE NOTE: Any of the views expressed by the speakers do not necessarily represent the views of The Merciful Servant or any other projects it may have or intend to do. The Merciful Servant and it's affiliates do not advocate nor condone any unlawful activity towards any individual or community. -

2:36

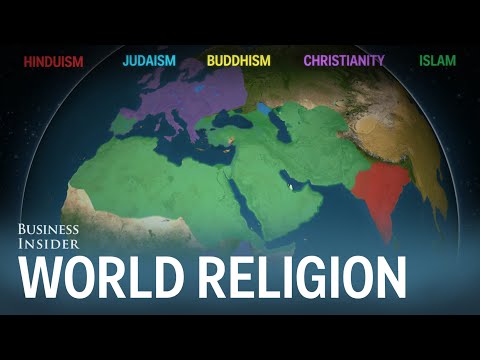

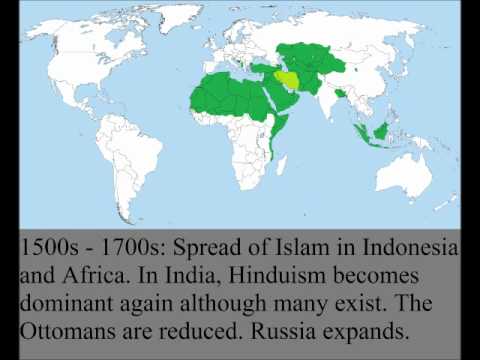

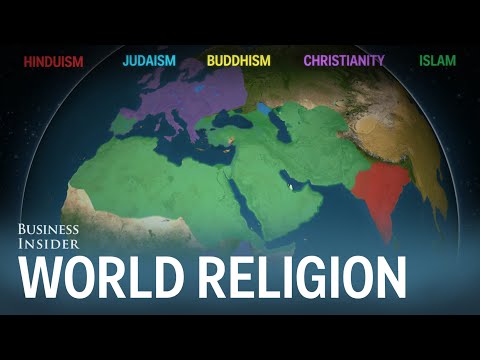

2:36Animated map shows how religion spread around the world

Animated map shows how religion spread around the worldAnimated map shows how religion spread around the world

Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam are five of the biggest religions in the world. Over the last few thousand years, these religious groups have shaped the course of history and had a profound influence on the trajectory of the human race. Through countless conflicts, conquests, missions abroad, and simple word of mouth, these religions spread around the globe and forever molded the huge geographic regions in their paths. -------------------------------------------------- Follow BI Video on Twitter: http://bit.ly/1oS68Zs Follow BI Video On Facebook: http://on.fb.me/1bkB8qg Read more: http://www.businessinsider.com/ -------------------------------------------------- Business Insider is the fastest growing business news site in the US. Our mission: to tell you all you need to know about the big world around you. The BI Video team focuses on technology, strategy and science with an emphasis on unique storytelling and data that appeals to the next generation of leaders – the digital generation. -

12:53

12:53Islam, the Quran, and the Five Pillars All Without a Flamewar: Crash Course World History #13

Islam, the Quran, and the Five Pillars All Without a Flamewar: Crash Course World History #13Islam, the Quran, and the Five Pillars All Without a Flamewar: Crash Course World History #13

Crash Course World History is now available on DVD! Visit http://store.dftba.com/products/crashcourse-world-history-the-complete-series-dvd-set to buy a set for your home or classroom. You can directly support Crash Course at http://www.patreon.com/crashcourse Subscribe for as little as $0 to keep up with everything we're doing. Free is nice, but if you can afford to pay a little every month, it really helps us to continue producing this content. In which John Green teaches you the history of Islam, including the revelation of the Qu'ran to Muhammad, the five pillars of Islam, how the Islamic empire got its start, the Rightly Guided Caliphs, and more. Learn about hadiths, Abu Bakr, and whether the Umma has anything to do with Uma Thurman (spoiler alert: it doesn't). Also, learn a little about the split between Sunni and Shia Muslims, and how to tell if this year's Ramadan is going to be difficult for your Muslim friends. Let's try to keep the flame wars out of this reasoned discussion. Follow us! @thecrashcourse @realjohngreen @raoulmeyer @crashcoursestan @saysdanica @thoughtbubbler Like us! http://www.facebook.com/youtubecrashcourse Follow us again! http://thecrashcourse.tumblr.com Support CrashCourse on Patreon: http://patreon.com/crashcourse -

1:01

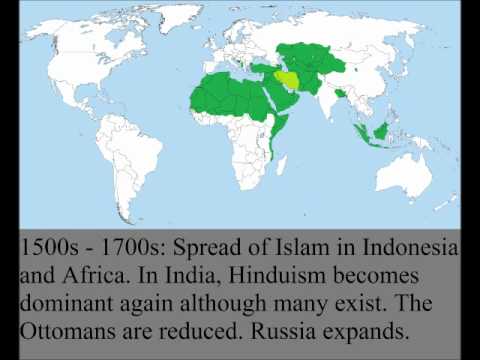

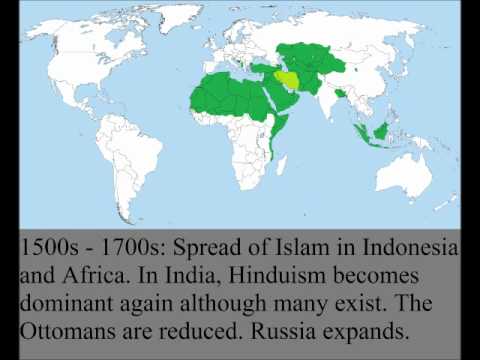

1:01The Spread of Islam

The Spread of IslamThe Spread of Islam

No hateful comments please. -

4:15

4:15Islam Spread By The Sword? ᴴᴰ | *Must Watch*

Islam Spread By The Sword? ᴴᴰ | *Must Watch*Islam Spread By The Sword? ᴴᴰ | *Must Watch*

Full Lecture link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2PIuIzkZAkg Islam spread by the sword? An amazing must watch reminder from brother Yusuf Estes answering the question, did Islam really spread by the sword? -

8:53

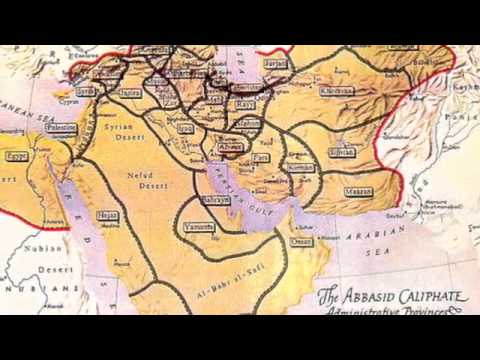

8:53Islam: beginning and spread

Islam: beginning and spreadIslam: beginning and spread

watch the beautiful history of Islam. Go to my channel for my videos similar to this. -

2:47

2:471300 Years of Islamic History in 3 Minutes

1300 Years of Islamic History in 3 Minutes1300 Years of Islamic History in 3 Minutes

The rise and fall of Muslim empires in the Middle East over 1300 years from the early 600s to the 1900s -

6:59

6:59فتى الدفينيه - Speed the spread of Islam in Europe and the world

فتى الدفينيه - Speed the spread of Islam in Europe and the worldفتى الدفينيه - Speed the spread of Islam in Europe and the world

-

7:31

7:31How to spread Islam in the modern world

How to spread Islam in the modern world -

7:55

7:55History Project- The Spread of Islam

History Project- The Spread of IslamHistory Project- The Spread of Islam

Spread of Islam -

10:31

10:31Mansa Musa and Islam in Africa: Crash Course World History #16

Mansa Musa and Islam in Africa: Crash Course World History #16Mansa Musa and Islam in Africa: Crash Course World History #16

In which John Green teaches you about Sub-Saharan Africa! So, what exactly was going on there? It turns out, it was a lot of trade, converting to Islam, visits from Ibn Battuta, trade, beautiful women, trade, some impressive architecture, and several empires. John not only cover the the West African Malian Empire, which is the one Mansa Musa ruled, but he discusses the Ghana Empire, and even gets over to East Africa as well to discuss the trade-based city-states of Mogadishu, Mombasa, and Zanzibar. In addition to all this, John considers emigrating to Canada. Crash Course World History is now available on DVD! http://store.dftba.com/products/crashcourse-world-history-the-complete-series-dvd-set Follow us! @thecrashcourse @realjohngreen @raoulmeyer @crashcoursestan @saysdanica @thoughtbubbler Like us! http://www.facebook.com/youtubecrashcourse Follow us again! http://thecrashcourse.tumblr.com Support CrashCourse on Patreon: http://patreon.com/crashcourse -

9:51

9:51Rise and Spread of Islam 500s-1400s

Rise and Spread of Islam 500s-1400s -

9:09

9:09The Spread of the Caliphate: The Islamic State (Part 1)

The Spread of the Caliphate: The Islamic State (Part 1)The Spread of the Caliphate: The Islamic State (Part 1)

Subscribe to VICE News here: http://bit.ly/Subscribe-to-VICE-News The Islamic State, a hardline Sunni jihadist group that formerly had ties to al Qaeda, has conquered large swathes of Iraq and Syria. Previously known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the group has announced their intention to reestablish the caliphate and declared their leader, the shadowy Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, as the caliph. Flush with cash and US weapons seized during recent advances in Iraq, the Islamic State’s expansion shows no sign of slowing down. In the first week of August alone, Islamic State fighters have taken over new areas in northern Iraq, encroaching on Kurdish territory and sending Christians and other minorities fleeing as reports of massacres emerged. Elsewhere in territory it has held for some time, the Islamic State has gone about consolidating power and setting up a government dictated by Sharia law. While the world may not recognize the Islamic State, in the Syrian city of Raqqa, the group is already in the process of building a functioning regime. VICE News reporter Medyan Dairieh spent three weeks embedded with the Islamic State, gaining unprecedented access to the group in Iraq and Syria as the first and only journalist to document its inner workings. In part one, Dairieh heads to the frontline in Raqqa, where Islamic State fighters are laying siege to the Syrian Army’s division 17 base. Watch our 5 Part documentary 'The Battle for Iraq' - http://bit.ly/1nmit6C Read Now: Total Chaos in Northern Iraq as Islamic State Takes Country's Largest Dam - http://bit.ly/1yaqbSO Check out the VICE News beta for more: http://vicenews.com Follow VICE News here: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/vicenews Twitter: https://twitter.com/vicenews Tumblr: http://vicenews.tumblr.com/ -

24:24

24:24Muslim Conquests And Spread Of Islam

Muslim Conquests And Spread Of IslamMuslim Conquests And Spread Of Islam

According to traditional accounts, the Muslim conquests (Arabic: الغزوات, al-Ġazawāt or Arabic: الفتوحات الإسلامية, al-Futūḥāt al-Islāmiyya) also referred to as the Islamic conquests or Arab conquests, began with the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. He established a new unified polity in the Arabian Peninsula which under the subsequent Rashidun (The Rightly Guided Caliphs) and Umayyad Caliphates saw a century of rapid expansion of Muslim power. They grew well beyond the Arabian Peninsula in the form of a Muslim empire with an area of influence that stretched from the borders of China and the Indian subcontinent, across Central Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, Sicily, and the Iberian Peninsula, to the Pyrenees. Edward Gibbon writes in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: Under the last of the Umayyad, the Arabian empire extended two hundred days journey from east to west, from the confines of Tartary and India to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. And if we retrench the sleeve of the robe, as it is styled by their writers, the long and narrow province of march of a caravan. We should vainly seek the indissoluble union and easy obedience that pervaded the government of Augustus and the Antonines; but the progress of Islam diffused over this ample space a general resemblance of manners and opinions. The language and laws of the Quran were studied with equal devotion at Samarcand and Seville: the Moor and the Indian embraced as countrymen and brothers in the pilgrimage of Mecca; and the Arabian language was adopted as the popular idiom in all the provinces to the westward of the Tigris. The Muslim conquests brought about the collapse of the Sassanid Empire and a great territorial loss for the Byzantine Empire. The reasons for the Muslim success are hard to reconstruct in hindsight, primarily because only fragmentary sources from the period have survived. Most historians agree that the Sassanid Persian and Byzantine Roman empires were militarily and economically exhausted from decades of fighting one another. The rapid fall of Visigothic Spain remains less easily explicable. Some Jews and Christians in the Sassanid Empire and Jews and Monophysites in Syria were dissatisfied and initially sometimes even welcomed the Muslim forces, largely because of religious conflict in both empires. In the case of Byzantine Egypt, Palestine and Syria, these lands had only a few years before being reacquired from the Persians, and had not been ruled by the Byzantines for over 25 years. Fred McGraw Donner, however, suggests that formation of a state in the Arabian peninsula and ideological (i.e. religious) coherence and mobilization was a primary reason why the Muslim armies in the space of a hundred years were able to establish the largest pre-modern empire until that time. The estimates for the size of the Islamic Caliphate suggest it was more than thirteen million square kilometers (five million square miles), making it larger than all current states except the Russian Federation. Frontier warfare continued in the form of cross border raids between the Umayyads and the Byzantine Isaurian dynasty allied with the Khazars across Asia Minor. Byzantine naval dominance and Greek fire resulted in a major victory at the Battle of Akroinon (739); one of a series of military failures of the Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik across the empire that checked the expansion of the Umayyads and hastened their fall. In the reign of Yazdgerd III, the last Sassanid ruler of the Persian Empire, an Arab Muslim army secured the conquest of Persia after their decisive defeats of the Sassanid army at the Battle of Walaja in 633 and Battle of al-Qādisiyyah in 636, but the final military victory didn't come until 642 when the Persian army was defeated at the Battle of Nahāvand. These victories brought Persia (modern Iran), Assyria (Assuristan) and Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and south east Anatolia under Arab Muslim rule. Then, in 651, Yazdgerd III was murdered at Merv, ending the dynasty. His son Peroz II escaped through the Pamir Mountains in what is now Tajikistan and arrived in Tang China.

- 613

- 630

- 682

- 711

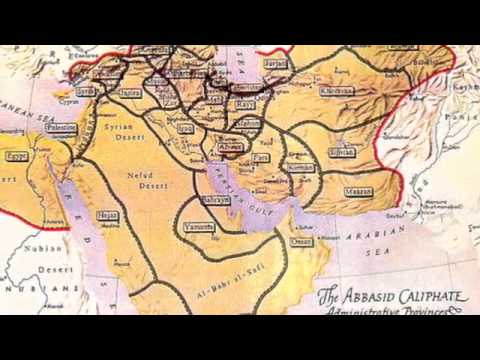

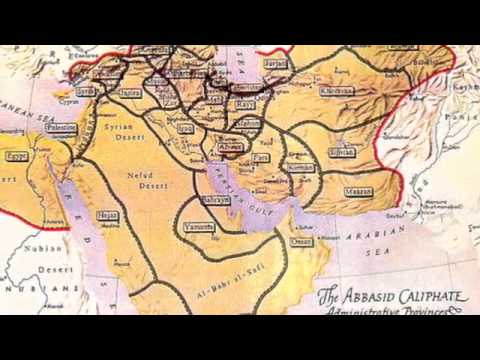

- Abbasid

- Abbasid Caliphate

- Abbasids

- Abdallah ibn Yasin

- Abyssinian

- Aceh

- Adal Sultanate

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Ahl al-Bayt

- Ahmad I bin Mohammed

- Ahmadiyya

- Ahriman

- Ahura Mazda

- Ajuuraan Empire

- Aksumite Empire

- Al Andalus

- Al-Andalus

- Al-Mansur

- Alexandria

- Ali

- Allah

- Almoravids

- Almış

- Angels in Islam

- Animist

- Arabia

- Arabian Peninsula

- Arabian peninsula

- Arabic

- Arabization

- Arculf

- Asia

- Asia Minor

- Assemani

- Atlantic Ocean

- Baghdad

- Balkans

- Bar-Hebraeus

- Basra

- Bat Ye'or

- Battle of Ain Jalut

- Battle of Talas

- Batu Khan

- Belgrade

- Bengal

- Berber people

- Berbers

- Berke

- Birth rates

- Blessed Sacrament

- Britannica

- Buddhism

- Buddhist

- Byzantine

- Byzantine Empire

- Byzantine-Arab Wars

- Caliph

- Caliph Omar

- Caliphate

- Caliphs

- Category Islam

- Central Asia

- Chagatai Khanate

- Christian

- Christianization

- Cloves

- Coconut

- Colonialism

- Communalism

- Conversion to Islam

- Converts to Islam

- Coral

- Covenant of Omar

- Damascus

- Dawah

- De Locis Sanctis

- Debal

- Dhimmi

- Dhimmis

- Dirham

- Druze

- East Africa

- Eastern Europe

- Edward Gibbon

- Egypt

- Ethiopia

- Eurabia

- Family reunification

- Far East

- Fatimids

- Ferdowsi

- Fertile crescent

- Fiqh

- First Crusade

- Friar

- Fujian

- Galangal

- Garrison

- Genghis Khan

- Ghazan

- Ghaznavids

- Ghurid Dynasty

- God in Islam

- Golden Age of Islam

- Golden Horde

- Guest workers

- Hadith

- Hajj

- Hanafi

- Harun al-Rashid

- Hindu

- Hinduism

- Holy Sepulchre

- House of Wisdom

- Hulagu

- Hulagu Khan

- Ibadi

- Iblis

- Ibn Battuta

- Ibn Batuta

- Ilkhanate

- Iman (concept)

- Immigration

- India

- Indian subcontinent

- Inhambane

- Inner Asia

- Ira Lapidus

- Iran

- Iranian plateau

- Islam

- Islam and animals

- Islam and children

- Islam and science

- Islam by country

- Islam in Ethiopia

- Islam in Europe

- Islam in India

- Islam in Somalia

- Islamic

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic art

- Islamic calendar

- Islamic culture

- Islamic holy books

- Islamic Law

- Islamic mysticism

- Islamic philosophy

- Islamic studies

- Islamic theology

- Islamism

- Islamization

- Islamization in Iran

- Ismailis

- Java

- Javanese people

- Jerusalem

- Jizya

- Jochi

- Kairouan

- Kalam

- Kara-Khanid Khanate

- Karluks

- Kashgaria

- Kazakh Steppe

- Kazakhs

- Kazakhstan

- Kerala

- Khazar-Arab Wars

- Khazars

- Khilji dynasty

- Kilwa Kisiwani

- Kilwa Sultanate

- Kodungallur

- Late antiquity

- Liberal Islam

- Log pod Mangartom

- Madrasa

- Mahdi

- Majapahit Empire

- Makkah

- Malabar region

- Malacca

- Malik Bin Deenar

- Malindi

- Mappila

- Marco Polo

- Marwan

- Marwanid

- Mawali

- Mecca

- Mediterranean

- Melayu Kingdom

- Menara Kudus Mosque

- Middle East

- Mindanao

- Missionaries

- Moghulistan

- Mombasa

- Mongol

- Mongol Empire

- Mongol invasion

- Monophysite

- Moriscos

- Morocco

- Mosque

- Mosque of Omar

- Mosque of Uqba

- Mughal Emperor

- Mughal Empire

- Muhammad

- Muslim

- Muslim conquests

- Muslim history

- Muslim holidays

- Muslim world

- Muslims

- Muslims in Europe

- Naqshbandi

- Nation of Islam

- Nestorian Church

- New Guinea

- Nigeria

- Nile Valley

- North Africa

- Nutmeg

- Orang-utan

- Ottoman empire

- Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman Sultan

- Pacific Ocean

- Pamirs

- Parameswara (sultan)

- Partition of India

- Pasai

- Pechenegs

- Persia

- Persian language

- Peureulak

- Pew Forum

- Portal Islam

- Prophets in Islam

- Prophets of Islam

- Puranas

- Qarakhanid dynasty

- Qur'an

- Quran

- Quranism

- Quraysh tribe

- Raja

- Rashidun

- Rashidun Caliphate

- Rashidun Empire

- Red Sea

- Religious conversion

- Rhinoceros

- Richard Bulliet

- Rumelia

- Rural

- Russian Federation

- Sacrament

- Safavid

- Safavids

- Saffarid dynasty

- Sahaba

- Sahara

- Saint

- Salah

- Samanids

- Sassanid

- Sassanid Empire

- Sawm

- Seljukids

- Shah Jahan

- Shahada

- Shahnameh

- Shaman

- Sharia

- Sheikh

- Shia Islam

- Shiraz

- Shirazi people

- Sicily

- Silver

- Sinbad the Sailor

- Slovenia

- Sokoto Caliphate

- Somali people

- Somalia

- South East Asia

- Southeast Asia

- Spice trade

- Spread of Islam

- Sufi

- Sufi missionaries

- Sufism

- Sultanate

- Sultanate of Malacca

- Sumatra

- Sunnah

- Sunni Islam

- Swahili coast

- Taraz

- Tariqah

- Tawhid

- Template Islam

- Template talk Islam

- The Sudan

- Thomas Walker Arnold

- Thrissur

- Timbuktu

- Timurid dynasty

- Treaty of Carlowitz

- Tunisia

- Turgesh

- Turkic peoples

- Turkish people

- Uganda

- Ulus of Jochi

- Umar

- Umar ibn AbdulAziz

- Umar II

- Umayyad

- Umayyad Caliphate

- Umayyad Dynasty

- Ummah

- Urban area

- Usman dan Fodio

- Uzbeg Khan

- Uzbeks

- Vishnu

- Volga Bulgaria

- Volga Tatars

- Warsangali Empire

- West Africa

- Western Asia

- William of Rubruck

- Women in Islam

- World War I

- Xinjiang

- Zakat

- Zakāt

- Zanzibar

- Zeila

- Zoroastrianism

- Aceh

- Afghanistan

- Al Andalus

- Alexandria

- Arabian Peninsula

- Arabian peninsula

- Atlantic Ocean

- Baghdad

- Basra

- Battle of Talas

- Belgrade

- Damascus

- Egypt

- Ethiopia

- Fujian

- India

- Inhambane

- Iran

- Jerusalem

- Kairouan

- Kazakhstan

- Kerala

- Kilwa Kisiwani

- Kodungallur

- Log pod Mangartom

- Malacca

- Malindi

- Mecca

- Mindanao

- Mombasa

- Morocco

- Mosque of Uqba

- Mughal Empire

- Nigeria

- Pacific Ocean

- Sahara

- Shiraz

- Shirazi people

- Sicily

- Slovenia

- Sokoto Caliphate

- Somalia

- Taraz

- Thrissur

- Timbuktu

- Tunisia

- Uganda

- Xinjiang

- Zanzibar

- Zeila

- Abdallah ibn Yasin

- Ali

- Assemani

- Batu Khan

- Berber people

- Berke

- Edward Gibbon

- Ferdowsi

- Genghis Khan

- Ghazan

- Hulagu Khan

- Ibn Battuta

- Javanese people

- Jochi

- Kazakhs

- Mappila

- Marco Polo

- Muhammad

- Pechenegs

- Rashidun

- Rashidun Caliphate

- Richard Bulliet

- Shah Jahan

- Shirazi people

- Sinbad the Sailor

- Somali people

- Thomas Walker Arnold

- Turgesh

- Turkic peoples

- Turkish people

- Umar

- Umar II

- Usman dan Fodio

- Uzbeks

- William of Rubruck

- World War I

-

The Untold History - How Islam Spread

► Support the Series: https://www.gofundme.com/untoldhistory ► Subscribe Now: https://goo.gl/2tmfa8 Official Website: http://www.themercifulservant.com MS Official Channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/TheMercifulServant MercifulServant FB: https://www.facebook.com/MercifulServantHD My Personal Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mercifulservant MS Twitter: https://twitter.com/MercifulServnt MS Instagram: http://instagram.com/mercifulservant MS SoundCloud: http://www.soundcloud.com/mercifulservant PLEASE NOTE: Any of the views expressed by the speakers do not necessarily represent the views of The Merciful Servant or any other projects it may have or intend to do. The Merciful Servant and it's affiliates do not advocate nor condone any unlawful activity towards any individual or communit... -

Animated map shows how religion spread around the world

Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam are five of the biggest religions in the world. Over the last few thousand years, these religious groups have shaped the course of history and had a profound influence on the trajectory of the human race. Through countless conflicts, conquests, missions abroad, and simple word of mouth, these religions spread around the globe and forever molded the huge geographic regions in their paths. -------------------------------------------------- Follow BI Video on Twitter: http://bit.ly/1oS68Zs Follow BI Video On Facebook: http://on.fb.me/1bkB8qg Read more: http://www.businessinsider.com/ -------------------------------------------------- Business Insider is the fastest growing business news site in the US. Our mission: to tell you all you n... -

Islam, the Quran, and the Five Pillars All Without a Flamewar: Crash Course World History #13

Crash Course World History is now available on DVD! Visit http://store.dftba.com/products/crashcourse-world-history-the-complete-series-dvd-set to buy a set for your home or classroom. You can directly support Crash Course at http://www.patreon.com/crashcourse Subscribe for as little as $0 to keep up with everything we're doing. Free is nice, but if you can afford to pay a little every month, it really helps us to continue producing this content. In which John Green teaches you the history of Islam, including the revelation of the Qu'ran to Muhammad, the five pillars of Islam, how the Islamic empire got its start, the Rightly Guided Caliphs, and more. Learn about hadiths, Abu Bakr, and whether the Umma has anything to do with Uma Thurman (spoiler alert: it doesn't). Also, learn a little ... -

The Spread of Islam

No hateful comments please. -

Islam Spread By The Sword? ᴴᴰ | *Must Watch*

Full Lecture link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2PIuIzkZAkg Islam spread by the sword? An amazing must watch reminder from brother Yusuf Estes answering the question, did Islam really spread by the sword? -

Islam: beginning and spread

watch the beautiful history of Islam. Go to my channel for my videos similar to this. -

1300 Years of Islamic History in 3 Minutes

The rise and fall of Muslim empires in the Middle East over 1300 years from the early 600s to the 1900s -

فتى الدفينيه - Speed the spread of Islam in Europe and the world

-

-

History Project- The Spread of Islam

Spread of Islam -

Mansa Musa and Islam in Africa: Crash Course World History #16

In which John Green teaches you about Sub-Saharan Africa! So, what exactly was going on there? It turns out, it was a lot of trade, converting to Islam, visits from Ibn Battuta, trade, beautiful women, trade, some impressive architecture, and several empires. John not only cover the the West African Malian Empire, which is the one Mansa Musa ruled, but he discusses the Ghana Empire, and even gets over to East Africa as well to discuss the trade-based city-states of Mogadishu, Mombasa, and Zanzibar. In addition to all this, John considers emigrating to Canada. Crash Course World History is now available on DVD! http://store.dftba.com/products/crashcourse-world-history-the-complete-series-dvd-set Follow us! @thecrashcourse @realjohngreen @raoulmeyer @crashcoursestan @saysdanica @thoughtbub... -

-

The Spread of the Caliphate: The Islamic State (Part 1)

Subscribe to VICE News here: http://bit.ly/Subscribe-to-VICE-News The Islamic State, a hardline Sunni jihadist group that formerly had ties to al Qaeda, has conquered large swathes of Iraq and Syria. Previously known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the group has announced their intention to reestablish the caliphate and declared their leader, the shadowy Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, as the caliph. Flush with cash and US weapons seized during recent advances in Iraq, the Islamic State’s expansion shows no sign of slowing down. In the first week of August alone, Islamic State fighters have taken over new areas in northern Iraq, encroaching on Kurdish territory and sending Christians and other minorities fleeing as reports of massacres emerged. Elsewhere in territory it has held fo... -

Muslim Conquests And Spread Of Islam

According to traditional accounts, the Muslim conquests (Arabic: الغزوات, al-Ġazawāt or Arabic: الفتوحات الإسلامية, al-Futūḥāt al-Islāmiyya) also referred to as the Islamic conquests or Arab conquests, began with the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. He established a new unified polity in the Arabian Peninsula which under the subsequent Rashidun (The Rightly Guided Caliphs) and Umayyad Caliphates saw a century of rapid expansion of Muslim power. They grew well beyond the Arabian Peninsula in the form of a Muslim empire with an area of influence that stretched from the borders of China and the Indian subcontinent, across Central Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, Sicily, and the Iberian Peninsula, to the Pyrenees. Edward Gibbon writes in The History of the Decline and Fall o... -

How Did Radical Islam Get Spread Throughout the World?

Much of the middle-east was once more secular. What changed? Cenk Uygur, hosts of the The Young Turks, breaks it down. Tell us what you think in the comment section below. Read this via BEN NORTON at Salon.com: http://www.salon.com/2015/11/17/we_created_islamic_extremism_those_blaming_islam_for_isis_would_have_supported_osama_bin_laden_in_the_80s/ "Where did violent Islamic extremism come from? In the wake of the horrific Paris attacks on Friday, November the 13, this is the question no one is asking — yet it is the most important one of all. If one doesn’t know why a problem emerged, if one cannot find its root, one will never be able to solve and uproot it. Where did militant Salafi groups like ISIS and al-Qaida come from? The answer is not as complicated as many make it out to be — b... -

The Spread of Islam and the Progress of the Caliphates Video Lesson and Example Education Portal

-

Who is Preventing the Spread of Islam? Is it Muslims? - Jeffrey Lang

Watch the full lecture at: http://youtu.be/KI3tEeESnLU Buy the DVD, CD or Download at http://www.islamondemand.com/278iod.html The Islam On Demand iPhone App: http://www.islamondemand.com/app Download our titles right now from... iTunes: http://www.IslamOnDemand.com/itunes Google Play: http://www.IslamOnDemand.com/play Amazon: http://www.IslamOnDemand.com/amazon The App Store: http://www.IslamOnDemand.com/appstore BUY DVDs, CDs & MP3s: http://www.IslamOnDemand.com FOLLOW US: Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/islamondemand Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/islamondemand Email List: http://www.islamondemand.com/subscribe YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/islamondemand PARTNER WITH US: http://www.islamondemand.com/affiliate TERMS OF USE: We are the original producer of this video. You ma... -

Secular State? Spread of Islam puts tough question of what is main UK religion

The rise in anti-Muslim sentiment in the UK is making some MPs consider whether even the Christian Bible should be read out loud in public. The fear is it could incite religious hatred amid already tense times. RT LIVE http://rt.com/on-air Subscribe to RT! http://www.youtube.com/subscription_center?add_user=RussiaToday Like us on Facebook http://www.facebook.com/RTnews Follow us on Twitter http://twitter.com/RT_com Follow us on Instagram http://instagram.com/rt Follow us on Google+ http://plus.google.com/+RT Listen to us on Soundcloud: https://soundcloud.com/rttv RT (Russia Today) is a global news network broadcasting from Moscow and Washington studios. RT is the first news channel to break the 1 billion YouTube views benchmark. -

Islam: Spread of Islam (Mecca)

-

WHAP Ch. 6 - Rise and Spread of Islam

The first global civilization, the Islamic Caliphate, begins in the 600s and rapidly spreads throughout the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, and Central Asia. -

Spread of Islam in Indonesia (Subtitle Indonesia)

CLICK HERE for the complete playlists and more interesting topics http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLUl5tU84odruUn8TW_SNzRL78nN6mL6d9 -

Islam, 1400 years spread by murder-by Dr Bill Warner.

Please note this is not Bill Warner but re uploaded. Also Bill has some facts that are worth listening to but note that his age and lack of using the internet shows he is not up on modern technology. We can respect that given his age. Islam is a distructive political system married to religion to give it strength and power. The true history of its nature is layed out here for all to see how evil Islam is. Most Muslims let alone others are not aware of this history. Some are whose ancestors died in its wake. killing of 260 million people is not the way religion should work. How anyone can believe this silly religion is beyond belief. -

West Africa: Stateless Societies and the Spread of Islam

This lesson looks at the stateless societies that existed in West Africa prior to the expansion of Islam and how the introduction of Islam gave the region the tools to build complex civilizations--namely, literacy, religion, and a legal system. Don't forget to hit the Like and Subscribe videos to make sure you receive notifications about upcoming Literature, Grammar, Reading, Writing, and World History lessons from MrBrayman.Info. Below is the outline of the slides used in the lesson: Stateless Societies and the Spread of Islam Part One of a Four-Part Series on Africa in the Post-Classical Period Africa is a Continent Americans often describe Africa as if it is a country... It is still the most diverse continent in the world History is about generalizations (scope) Generalizations abo...

The Untold History - How Islam Spread

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 19:08

- Updated: 15 Jan 2016

- views: 77398

- published: 15 Jan 2016

- views: 77398

Animated map shows how religion spread around the world

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:36

- Updated: 14 Jul 2015

- views: 1260725

- published: 14 Jul 2015

- views: 1260725

Islam, the Quran, and the Five Pillars All Without a Flamewar: Crash Course World History #13

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 12:53

- Updated: 19 Apr 2012

- views: 3275822

- published: 19 Apr 2012

- views: 3275822

The Spread of Islam

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:01

- Updated: 18 Jul 2012

- views: 49807

- published: 18 Jul 2012

- views: 49807

Islam Spread By The Sword? ᴴᴰ | *Must Watch*

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:15

- Updated: 26 Mar 2015

- views: 14959

- published: 26 Mar 2015

- views: 14959

Islam: beginning and spread

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 8:53

- Updated: 20 Jun 2010

- views: 7634

- published: 20 Jun 2010

- views: 7634

1300 Years of Islamic History in 3 Minutes

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:47

- Updated: 05 Jan 2014

- views: 258769

- published: 05 Jan 2014

- views: 258769

فتى الدفينيه - Speed the spread of Islam in Europe and the world

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:59

- Updated: 13 Jul 2012

- views: 9413

- published: 13 Jul 2012

- views: 9413

How to spread Islam in the modern world

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:31

- Updated: 16 Oct 2011

- views: 19208

History Project- The Spread of Islam

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:55

- Updated: 17 Oct 2011

- views: 16781

Mansa Musa and Islam in Africa: Crash Course World History #16

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:31

- Updated: 10 May 2012

- views: 1479895

- published: 10 May 2012

- views: 1479895

Rise and Spread of Islam 500s-1400s

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:51

- Updated: 07 Jul 2010

- views: 22649

The Spread of the Caliphate: The Islamic State (Part 1)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:09

- Updated: 07 Aug 2014

- views: 7883180

- published: 07 Aug 2014

- views: 7883180

Muslim Conquests And Spread Of Islam

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 24:24

- Updated: 03 Feb 2014

- views: 16475

- published: 03 Feb 2014

- views: 16475

How Did Radical Islam Get Spread Throughout the World?

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 17:27

- Updated: 26 Nov 2015

- views: 153166

- published: 26 Nov 2015

- views: 153166

The Spread of Islam and the Progress of the Caliphates Video Lesson and Example Education Portal

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:27

- Updated: 16 Oct 2015

- views: 211

- published: 16 Oct 2015

- views: 211

Who is Preventing the Spread of Islam? Is it Muslims? - Jeffrey Lang

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:38

- Updated: 17 Jul 2013

- views: 21166

- published: 17 Jul 2013

- views: 21166

Secular State? Spread of Islam puts tough question of what is main UK religion

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:21

- Updated: 31 Jan 2016

- views: 14071

- published: 31 Jan 2016

- views: 14071

Islam: Spread of Islam (Mecca)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:13

- Updated: 23 Nov 2013

- views: 2247

- published: 23 Nov 2013

- views: 2247

WHAP Ch. 6 - Rise and Spread of Islam

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 13:08

- Updated: 07 Oct 2014

- views: 1995

- published: 07 Oct 2014

- views: 1995

Spread of Islam in Indonesia (Subtitle Indonesia)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 11:51

- Updated: 25 Apr 2013

- views: 2045

- published: 25 Apr 2013

- views: 2045

Islam, 1400 years spread by murder-by Dr Bill Warner.

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 44:50

- Updated: 13 Sep 2012

- views: 60041

- published: 13 Sep 2012

- views: 60041

West Africa: Stateless Societies and the Spread of Islam

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:29

- Updated: 17 Apr 2014

- views: 768

- published: 17 Apr 2014

- views: 768

- Playlist

- Chat

- Playlist

- Chat

The Untold History - How Islam Spread

- Report rights infringement

- published: 15 Jan 2016

- views: 77398

Animated map shows how religion spread around the world

- Report rights infringement

- published: 14 Jul 2015

- views: 1260725

Islam, the Quran, and the Five Pillars All Without a Flamewar: Crash Course World History #13

- Report rights infringement

- published: 19 Apr 2012

- views: 3275822

The Spread of Islam

- Report rights infringement

- published: 18 Jul 2012

- views: 49807

Islam Spread By The Sword? ᴴᴰ | *Must Watch*

- Report rights infringement

- published: 26 Mar 2015

- views: 14959

Islam: beginning and spread

- Report rights infringement

- published: 20 Jun 2010

- views: 7634

1300 Years of Islamic History in 3 Minutes

- Report rights infringement

- published: 05 Jan 2014

- views: 258769

فتى الدفينيه - Speed the spread of Islam in Europe and the world

- Report rights infringement

- published: 13 Jul 2012

- views: 9413

How to spread Islam in the modern world

- Report rights infringement

- published: 16 Oct 2011

- views: 19208

History Project- The Spread of Islam

- Report rights infringement

- published: 17 Oct 2011

- views: 16781

Mansa Musa and Islam in Africa: Crash Course World History #16

- Report rights infringement

- published: 10 May 2012

- views: 1479895

Rise and Spread of Islam 500s-1400s

- Report rights infringement

- published: 07 Jul 2010

- views: 22649

The Spread of the Caliphate: The Islamic State (Part 1)

- Report rights infringement

- published: 07 Aug 2014

- views: 7883180

Muslim Conquests And Spread Of Islam

- Report rights infringement

- published: 03 Feb 2014

- views: 16475

Torture Is Never Forgotten, Neither Should It Be

Edit WorldNews.com 13 Apr 2016Strong Earthquake Strikes Northern Myanmar

Edit WorldNews.com 13 Apr 2016North Korea deploys intermediate-range missiles, report says

Edit The Times of India 14 Apr 2016FBI Employed Hackers To Break Into San Bernardino Cell Phone, Report Says

Edit WorldNews.com 13 Apr 2016Lincoln Lewis' girlfriend Chloe Ciesla goes topless as she poses for a holiday snap by ...

Edit The Daily Mail 13 Apr 2016Militant attack in Tunisia may signal further spread of Islamic State

Edit The Los Angeles Times 08 Mar 2016Tarnishing global image of Islam, West's main plot to prevent spread of Islam

Edit Irna 01 Jan 2016European Union police agency to fight spread of Islamic State group propaganda on social media

Edit Star Tribune 22 Jun 2015IRGC official: West fearful of spread of Islamic Revolution dialogue

Edit Irna 03 Jan 2015- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Next page »