This blog was created as an outlet for some of my written work. I have also used it to record a few of my other activities. Hopefully people will find it interesting or useful. I was going to call it – democracy, peace and love – because that’s what I’m most interested in. However, I decided on revolts now in memory of my first zine, revolt now, produced during my high school years. At that time I thought of revolution as an event, but now I think of it as a historical process, a long series of varied events in the past, present and future. The name revolt now had already been taken but revolts now was available. So here it is.

Once upon a time . . . I decided to write about fictitious capital and the term ‘extend and pretend’.

At a friend’s NYE party he voiced confusion about the way capitalism values things. I replied that this meant he had a good grasp of the current situation. For those at the party concerned about their house prices, superannuation, pensions, investments, etc., our conversation wasn’t very reassuring. They preferred the story where you work hard, save, invest and can rely on the system to reward you. Yet, like many, they worry this is a fading illusion. Nevertheless, what choice do they have, but to keep going and imagine things will be OK?

‘Extend and pretend’ has become a popular way to describe the current situation in Greece, where the nation’s debts cannot be repaid, so their lenders extend loans, provide more loans, and pretend they’ll get their money back later. This popular fiction is supposed to defer greater economic crisis and collapse, by putting off dealing with reality until sometime in the future. More generally ‘extend and pretend’ is the motto of ‘late capitalism’ in the face of a growing range of existential crises.

The ‘extend and pretend’ story of Greece is a tale of democracy. You know the one – people vote in elections, they’re represented by politicians, and citizens get a say in government policies. Most likely, since you’re reading this blog, you also understand there’s a ruling class and corporate power is greater than that of any parliament. This was clearly demonstrated last year, when the hope and disappointment of the Syriza government revealed how state forms, elections, and popular votes can be subordinated to finance capital and ‘market forces’.

A popular tale of capitalist institutions is that economic decision making is ‘technical’ or ‘administrative’, rather than political, as if class struggle wasn’t at the heart of social history. In the ‘birthplace of democracy’, we saw how a nation’s future rests on the country’s credit rating and the demands of financial managers. The façade of democracy was exposed, as the impossibility of national governments deciding economic policies without the consent of ‘the market’ became clear.

Whose script . . ?

In 2008, the near-collapse of the global financial system was overcome through the conversion of bank debts into government debts and the implementation of austerity policies in many parts of the world. After being rescued with taxpayer’s money, the banking bosses voted that financial discipline was now required from the governments and people who’d saved them. This tragedy saw Greece in the spotlight, as a series of austerity measures was enforced, so new loans could be provided to ‘keep the country afloat’, even though there’s no way the mounting debts can ever be paid back. Austerity shrunk the Greek economy dramatically. Tens of thousands of businesses closed down. More than a million people lost their jobs and half of all young people are unemployed. Welfare benefits and government services have been slashed – poverty is widespread.

Last year, when Syriza won the national elections and formed a new anti-austerity government, it was made clear that their election wouldn’t be allowed to interfere with the economic policies being prescribed by the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Instead they were commanded to execute further cuts – in order to get more loans, just to make the nation’s debt repayments. Then, in a national referendum, Greek voters rejected austerity. But in a vicious plot twist the financial institutions forced the closer of Greek banks and created a more severe economic and social crisis. The government’s resistance was broken and they agreed to deeper budget cuts, continued privatisation of government assets, more job losses, and an ongoing social disaster.

For many parts of the world this is a familiar story. When ‘the market’ decides that discipline is required, we witness the structural adjustment programs or ‘shock therapy’ prescriptions of the IMF, World Bank, ECB, etc. Again and again, people and governments are called on to demonstrate their subservience to capital, or face the consequences.

Fictitious capital

Like the fables of capitalist democracy, I have long found it annoying how those who write economic theory tell stories about ‘fantasy scenarios’ to explain the unreal worlds they describe. However, when we explore fictitious capital; ‘all that is solid melts into air’. Fictitious capital includes credit, shares, bonds, speculation and various forms of money, whose value is based on imagined future earnings. Banks and other financial institutions sell these claims to future profits, generating and accumulating more fictitious capital. When banks loan out more money than they possess, they create fictitious capital. Most of the lending done by banks is to other banks and financial institutions, buying and selling fictitious capital to each other – making bets with each other about whether the price of this capital will rise or fall in the coming days. The narrative of this fiction is constructed by means of a balancing act performed by the most powerful governments and banks, as fictitious capital is continually invented as a symbol of confidence in the future of capitalism.

There’s no clear distinction between capital which is ‘real’ and capital which is fictitious. As this becomes more widely understood, capitalism appears as precarious and crisis ridden to governments, banks, and corporate bosses as it does to us. Because people around the world have resisted paying for the current crises and have intensified their struggles against capital, the imagined gains from fictitious capital must be postponed for longer and longer and the promise of future profits must be renewed again and again. With little belief in the long-term viability of their accumulated wealth, capitalist gangs fight each other in destructive turf wars, intensifying the crises of capitalism and destroying the basis for continuing expansion and growth. As crisis intensifies, the main source of new capital is the continued fiction conjured up in the finance sector. Today, global trade in actual goods is only a tiny fraction of the trade in various forms of finance capital and the mass of fictitious capital circulating in the money markets, futures exchanges, and so on, is far greater than ever before. The market value of such capital is a creation of supply and demand factors which are manipulated for profit in a global story-telling contest. As fictitious capital has become the engine of production and capital accumulation, the whole system is increasingly precarious, reliant on continuing confidence in a concocted system, tottering from crisis to crisis.

Money talks . . . shit

There remains a popular fable that money has to be earned, even though the rich tend to be born with their wealth and/or steal it. The value of money is another fiction, fabricated by the world’s central banks and commercial financial institutions. A central bank introduces new money into the economy by purchasing bank deposits, bonds or stocks or by lending money to other financial bodies. Commercial banks borrow money and then multiply this money by creating interest bearing loans (most of this money exists only as a book-keeping entry). These loans are then considered to be among the bank’s assets. Since the GFC, China, USA, Britain, Japan and the Eurozone have created an estimated $12 trillion of money which didn’t previously exist. This money may appear to offer a reliable measure of wealth, yet many of us are familiar with how the value of money can fall (like the Australian dollar) or totally disintegrate (e.g. in Germany during the 1920s or Zimbabwe in 2008 when the inflation rate was estimated at 231,000,000% – yes 231 million) and how access to your money can disappear overnight (e.g. in Argentina 2001, Iceland 2008, Cyprus 2013).

Last year, annual inflation in Venezuela hit over 140 percent. According to the country’s Central Bank, the lion’s share of this was caused by currency manipulation (deliberate attacks on the value of Venezuelan money) as part of an ‘economic war’ to bring down the country’s socialist government. Currency manipulation and speculation, rigging and betting on the ‘value’ of money, is the largest market/scam in history, estimated at a couple of quadrillion dollars per year (that’s two million billion dollars). As discussed below, the institutions dominating this multi-trillion-dollar-a-day trade are able to stage-manage the way they play with money as a form of sophisticated criminal theatre. Yet, in his latest book, Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism, Professor David Harvey sounds a warning about the growing destabilisation of money, arguing that; “The rise of cyber moneys, like Bitcoin, in some instances seemingly constructed for purposes of money-laundering around illegal activities, is just the beginning of an inexorable descent of the monetary system into chaos.”

Harvey details a range of illegal activities that are crucial to capitalist appropriation, including robbery, cheating, and swindling, along with a range of ‘shady practices’ such as price fixing, Ponzi schemes, falsification of asset valuations, interest rate manipulation and money laundering, while arguing; “it is stupid to seek to understand the world of capital without engaging with the drug cartels, traffickers in arms and the various mafias and other criminal forms of organisation that play such a significant role in world trade.” Yet, if we are to explore and try to understand the lawless underworld, we shouldn’t neglect how the global finance industry is constructed by and for criminal activities, and what this could mean when considering the potential collapse of the monetary system.

My favourite TV show last year was the second season of Fargo. This fiction revolved around a criminal gang war in the 1970s, and its impact on two families and two communities. The final episode opens with a roll call of all the bodies that have piled up around Fargo and Dakota over the previous episodes. The big city crime ‘Syndicate’ has come out on top and their hitman, Mike Milligan, has seemingly made every correct step in advancing through the bloodshed. He avoids the slaughters and takes out those who stand in his way, but when he gets back to base, hoping to become the new territory’s top dog, he’s instead promoted to the accounting department. “This is the future,” his crime boss tells him. “The sooner you realise there’s only one business left in the world, the money business, just ones and zeroes, the better off you’re gonna be.”

There once lived some . . . banksters

Many people have a traditional view of banks – we deposit money, they loan money, and make investments. Yet, when we get angry about their fees, charges, and obscene profits, we often complain ‘they’re robbing us’. This criticism is fairly accurate – commercial banks are corporations that steal money. Their theft is part of the more widespread ‘legal crimes’ of robbery and exploitation at the core of capitalism. As well, banks and bankers are often involved in a whole range of illegal criminal undertakings.

From popular fiction we know Swiss banks have long been a favoured repository of capital from illicit activities. The role of these banks in laundering Nazi loot and their complicity with the holocaust is legendary. More recently, banks in so-called ‘tax havens’ or ‘countries of financial secrecy’, such as the Canary Islands or the Bahamas, are regularly reproached for hiding away ill-gotten gains. Some readers may also recall the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) which collapsed in the early 1990s. BCCI was the seventh largest private bank in the world and a nest of corruption, money laundering and other secretive activities. In a report on the bank’s failure, John Kerry (at the time US Vice President and currently Secretary of State) explained; “BCCI’s criminality included fraud by BCCI and BCCI customers involving billions of dollars; money laundering in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas; BCCI’s bribery of officials in most of those locations; support of terrorism, arms trafficking, and the sale of nuclear technologies; management of prostitution; the commission and facilitation of income tax evasion, smuggling, and illegal immigration; illicit purchases of banks and real estate; and a panoply of financial crimes limited only by the imagination of its officers and customers.”

A long, long, time ago . . .

The collapse of BCCI was much like the fall of Australia’s legendary Nugan Hand bank in the 1970s. After this bank’s collapse, a Royal Commission found it was involved in money laundering, illegal tax avoidance schemes, and widespread violations of banking laws. The bank was also implicated in drug smuggling, illegal weapons deals, and providing a front for the criminal activities of the US Central Intelligence Agency.

Before the GFC, the US Savings and Loans (S&Ls) crisis of the 1980s and 1990s was the greatest bank collapse (described by many as a ‘robbery’) since the Great Depression. By 1989, more than one thousand S&Ls had failed, effectively ending what had once been a secure source of home mortgages. Many S&Ls were engaged in criminal practices, fraud, false accounting, forgery, and dishonest conduct as deliberate commercial policy. In 1996, the US General Accounting Office estimated the total cost of the S&Ls collapse to taxpayers at more than $132 billion.

The regular exposure of bank criminality includes the recent guilty pleas by four major global banks to manipulating the foreign money exchange market. They joined three other major banks shown to be involved in the same crime. These charges stem from an agreement by the banks not to commit more offences, after the ‘Libor scandal’ of 2012, involving the fraudulent manipulation of interest rates by a whole range of prominent financial institutions. Meanwhile, those who’ve closely followed the GFC and its aftermath will appreciate that the above examples are just the tip of an unfathomable criminal-banking iceberg.

The GFC also made clear that corporate criminals usually have the power to avoid charges and convictions. While the myth of a fair legal system, where law enforcement ensures goodness prevails, still holds some currency – it’s also commonly understood that the wealthy are protected and there’s ‘one law for them and another one for us’. The stories of ‘equality before the law’ and ‘criminal justice’ are now worn-out deceptions, evidenced by popular culture, where police, politicians, judges, and corporate bosses are regularly portrayed as crooked characters up to their necks in crime & corruption. Even though the poor are still more likely to be considered a ‘criminal class’, the fact that the most serious crimes are committed by the rich and powerful is increasingly understood. Yet, banksters don’t go to prison; instead the cells are reserved for their victims.

A factory of broken dreams . . .

Since the GFC and global recession began, there’s been a series of movies about the banking and finance industries (e.g. Wolf of Wall Street, Margin Call, Wall Street – Money Never Sleeps, The Big Short), often highlighting the crimes of banksters. In January, I went to see the latest of these – The Big Short, which is based on a ‘true story’ about the GFC.

Part of the film is set in a financial traders convention, appropriately held in Las Vegas, where the financial market is compared to a casino. Yet, what the movie could have made clearer was that for the major players, just like in a casino, ‘the bank always wins’ – for those deemed ‘too big to fail’ there was no serious risk of losing. These ‘players’ can gamble on almost anything, including betting on the failure of loans, the collapse of currencies, countries, other financial institutions, and even the bankruptcy of their own client’s. Major finance corporations like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and JP Morgan Chase, created fraudulent pyramid schemes, sold them to investors, and bet they would fail.

I used to be a keen punter and with some knowledge of how the gambling industry was used to swindle people and launder the proceeds of crime. So I based my selections on various theories about how racing was corrupt and the races rigged. Today, the revenue from the ‘legal’ gambling industry is estimated to be around $US500 billion per year. Illegal gambling turnover is believed to run into the trillions of dollars. Yet, this is nothing compared to the hundreds of trillions of dollars’ worth of bets on various fictional accounts of the future and the assorted ways of measuring these fictions. Despite its weaknesses, The Big Short was disturbing, especially if you have a lot of money in a bank, financial institution, pension fund, etc., since it made a strong case that these were all on the gambling table and at any moment you could lose everything to the villains who run the game.

Another disturbing movie, from 2010, is the academy award winning documentary Inside Job. This film centres on the systemic corruption of the United States by the finance industry and what the filmmakers term the ‘biggest bank heist in world history’ – the theft of trillions of dollars, leading up to and during the GFC, by those in charge of the major financial institutions. As the film makes clear, this robbery was facilitated by a revolving door between the banks and the higher reaches of government, where bank/financial corporation CEOs become government officials, creating laws convenient for their past/future employers. To indicate how pervasive this revolving door is, we only need to consider the involvement of banking, securities and investment firm Goldman Sachs in the governments of USA, Nigeria, Egypt, Spain, Czech republic, Italy, Sweden, and the appointment of their directors as heads of the Bank of England, the Bank of Greece, and the European Central Bank. And let’s not forget the current Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, was previously the chair and managing director of Goldman Sachs Australia.

As Inside Job explores, during the GFC the financial system froze up and it appeared the global economy may come to a halt, after investment banks Lehman Brothers, Bear Sterns and Merrill Lynch collapsed. Yet, after the ‘biggest bank robbery in history’, the commercial banking sector was bailed out of the situation they’d created with trillions of dollars of money from national governments. Then, those who’d profited most from the crisis were put in charge of reforming the financial industry ‘to ensure a similar collapse didn’t happen again’. The result was larger and more powerful financial corporations conducting ‘business as usual’. Meanwhile many other businesses went broke, global stock markets dropped, and housing prices crashed, resulting in evictions, foreclosures and mass homelessness. Tens of millions of people lost their jobs and unemployment skyrocketed. Poverty rose and wealth was redistributed on a massive scale from workers/poor to the rich. Having bailed out the banks, governments around the world cut back expenditure, unleashed austerity programs, and normalised a prolonged crisis, which continues to this day.

Some readers may recall another popular documentary, from 2005, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, which gave some forewarning of the practices behind the GFC.

Enron was the seventh largest corporation in the US – buying and selling energy, running energy services and gambling on energy prices. Enron turned the energy industry into a casino, betting on the price of energy – while controlling the supply and creating a phoney energy crisis, involving rolling blackouts in California. For years, Enron always seemed to win – but this was a lie constructed using phoney accounting and falsified bank records/financial statements. Their fictitious earnings allowed them to publish imaginary profits, in order to maintain optimism in the firm and sustain a rising share price, while losing billions and getting deeper into debt, until the whole house of cards came crashing down. The CEOs cashed out their stocks, while the price was still high, and made off with the loot. Billions in investor, government, pension, and retirement funds disappeared.

Leading financial institutions assisted Enron’s deceptive practices, helping to design their fictions and profiting from them. Financial analysts at the time argued they didn’t understand how Enron was making money – “you just had to have faith in it.” When Enron went bankrupt (at that time the largest ever US corporate bankruptcy and widely described as the ‘corporate crime of the century’), the same people who’d received generous offerings from the firm were expected to investigate the company for fraud. Nearly every US Senator and member of the House of Representatives involved in the committees investigating Enron’s collapse, or the conduct of Enron’s accounting firm, had received donations from one or both companies.

Who pays the piper . . . ?

At the centre of the GFC was a crisis of debt and value. As the financial system went into meltdown the experts of finance and economics were at a loss to explain or calculate the value of shares, money and assets. They repeatedly exclaimed that the crisis was ‘too complex’, that they ‘lacked reliable data’; they didn’t know what had happened or was happening. This is a huge problem for the system, as it requires measuring processes and values that result in common activity for capitalism. Importantly, debt couldn’t be accurately valued. It became clear that trillions of dollars’ worth of loans were not going to be repaid – so most were ‘rolled over’ (becoming ‘new’ extended loans). Since then, debts have continued to grow faster than economies, with families, companies and governments borrowing an estimated $57 trillion more than they’d already borrowed.

Examining the debt situation in Greece, Slavoj Zizek argues; “The true goal of lending money to the debtor is not to get the debt reimbursed with a profit, but the indefinite continuation of the debt that keeps the debtor in permanent dependency and subordination.” Debts are meant to maintain a hierarchy of power, since the daily reproduction of capitalism is centred on social control through the imposition of work for capital. Yet John Holloway explains that: “Debt is essentially a game of make-believe: it is capital saying ‘if we cannot make the workers produce the profits we require, if we cannot impose the submission that we require, then we shall pretend that we can: we shall create a monetary image of the profits we need.’” Elsewhere (e.g. Radio Interview, Global Revolt, Class Struggle in China), I’ve supported an analysis that argues ‘we are the crisis of capital’ – that powerful resistance to and rebellion against capitalist work has thrown the system into question, there’s a widespread rejection of capitalist values, and the GFC was a generalised vote of ‘no confidence’ by ‘the market’ in both people’s willingness and ability to pay their debts.

Today, confidence in capitalist fictions is again at a very low level. Last month, the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) made headlines when it warned about growing debt, the coming “cataclysmic year”, and another crash; telling investors to “sell everything”. But before you follow their advice, it’s worth recalling that RBS was once a small retail bank, which transformed into one of the world’s largest. Then, during the GFC, went from a position of global leadership to a basket case – a failure that almost brought down the entire UK financial system. The bank’s collapse was only prevented by 45 billion pounds of taxpayer support and several hundred billions more in government loans.

A tale of . . . measuring the Emperor’s clothes

Over and over, around the globe, we hear a rising chorus of people asking – What is real and what is fiction? With a background in unemployed people’s organisations, I’ve long been aware that official unemployment rates and job creation numbers are made-up, with governments and statistical agencies ‘massaging’ and distorting the figures for political purposes. At a forum I attended last year, Victor Quirk, from the Centre of Full Employment and Equity at the University of Newcastle, estimated the actual unemployment rate in Australia at close to double the official number. Unemployment rates are among a range of measuring tools used to help maintain and reproduce the fictions of capitalism. These figures, statistics, and valuations are not objective truths, but creations reflecting widespread power struggles within, against, and outside of capital.

Economists tend to imagine an artificial world of graphs, tables and calculations, ‘invisible hands’, debts that are assets, and endless ‘growth’ that in fact destroys. Some have developed elaborate theories to calculate the finance industry’s ‘investments in investments’, ‘bets about bets’ and ‘bets about bets about bets’. However, these theories are mostly fables – tales told to keep us working and help us sleep. Economic theory and analysis relies on information provided by governments, banks, ratings agencies, and other mainstream institutions. Yet none of these can be trusted.

In 2007, economist Li Keqiang, currently China’s prime minister, let the American ambassador in on a secret: China’s GDP figures are “man-made” and therefore “unreliable.” He explained that most of the country’s economic data should be used for “reference only.” Recently, I read political economist Minq Li’s latest book, China and the 21st Century Crisis, which discusses the untrustworthiness of  official Chinese economic data, yet relies on this data to develop Li’s analysis of contemporary capitalist crisis. As we commonly find, in the absence of accurate information, people have limited options. It’s widely recognised that when considering China’s economy (on which so much now hinges) ‘we can’t trust the numbers’. Comparisons are sometimes drawn with the former Soviet Union. Although it was widely understood the Soviet government made-up many of their economic indicators, and was deluded about the political/social situation, it still came as a shock when this ‘super power’ collapsed.

official Chinese economic data, yet relies on this data to develop Li’s analysis of contemporary capitalist crisis. As we commonly find, in the absence of accurate information, people have limited options. It’s widely recognised that when considering China’s economy (on which so much now hinges) ‘we can’t trust the numbers’. Comparisons are sometimes drawn with the former Soviet Union. Although it was widely understood the Soviet government made-up many of their economic indicators, and was deluded about the political/social situation, it still came as a shock when this ‘super power’ collapsed.

Since the GFC, spending by the Chinese government has been a crucial factor in ‘combating global economic crisis’. It’s reported that between 2008 and 2014 available new loans in China rose by more than $US20 trillion. Apparently the Government has also spent over a trillion dollars on directly stimulating the economy. Yet fear of serious economic decline in ‘the world’s factory’ persists. Today, there’s little confidence Chinese policymakers know what they’re doing and growing concern that the Communist Party leadership are out of their depth is helping to destabilise ‘the markets’ and global economy.

In the world’s largest economy (apparently/for now) there’s a similar story. In 2008, the US government reportedly spent around a trillion dollars to stem systemic collapse. At the same time, as the finance industry went into crisis, in order to ‘save’ companies like General Electric, General Motors, Bank of America and Citi Group, the US Federal Reserve (as the lender of last resort) provided massive loans to corporations of all kinds. These corporations, like the banks, were ‘bailed out’, yet recession and economic instability continued. At the end of last year, a decision by the US Feder al Reserve to very slightly raise interest rates was meant to tell a story of confidence in US economic recovery. The fragility of this gambit was indicated by the Reserve’s statement that this measure was made partially so it could be rapidly reversed if things started getting worse. So far this year, ‘the market’s’ vote on US and Chinese political/economic narratives has been one of ‘no confidence’.

al Reserve to very slightly raise interest rates was meant to tell a story of confidence in US economic recovery. The fragility of this gambit was indicated by the Reserve’s statement that this measure was made partially so it could be rapidly reversed if things started getting worse. So far this year, ‘the market’s’ vote on US and Chinese political/economic narratives has been one of ‘no confidence’.

Just an opinion . . .

Among the key players in the world’s financial architecture are the main credit ratings agencies – Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch. They exist to assess the creditworthiness of corporations, institutions and countries who borrow money. Their ratings are meant to reveal how likely debts are to be paid back. A high rating indicates that a borrower’s finances are secure. But, surprise, surprise, the ratings are a fiction.

In 2001, it wasn’t until right before Enron declared bankruptcy that the agencies began to downgrade its credit rating. In 2007, the agencies rated Iceland’s banks at AAA (the highest possible) despite them borrowing $120 billion – ten times the size of the nation’s economy. Within a year, the banks had collapsed. And, in 2008, investment banks Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch were all highly rated just before they went bankrupt.

The ratings agencies are paid by those they’re meant to be assessing and rely on the accounts provided by them. They also cover-up and disguise problems their clients wish to hide, they miscalculate, misinform, and fail to appraise the ‘real’ situation of corporations, banks, and other financial institutions. Ratings agencies have made billions of dollars giving high ratings to fraudsters. In fact, the higher the rating given the more the agencies receive in payment. While Governments, investors, and ‘the market’, place great store on these ratings – the agencies themselves say they “are just their opinions and shouldn’t be relied on.” According to Standard and Poor’s, their ratings “should not be viewed as assurances of credit quality or exact measures of the likelihood of default.” Instead, the ratings should be considered a “commentary”.

None-the-less, these ratings have a direct impact on ‘the market’ and the wider economy. They are tremendously powerful ‘opinions’ and ‘commentaries’, with the potential for a downgrade to destroy a corporation, help bring down a government or destabilise a country. The agency’s ratings are repeatedly used as weapons by ‘market forces’ against states seeking to challenge the power of capital. At the same time, the agencies are key players in covering-up the crimes of the rich and powerful. Along with accounting firms, these key capitalist measuring instruments are sophisticated story tellers, weaving tales of punishment and discipline for most of us, and a web of lies for their corporate pay masters.

Not the whole story . . . ?

As David Harvey indicated above, much of the global economy is secretive, ‘hidden’ or in ‘the shadows’. This is commonly acknowledged through terms like the ‘grey economy’, which includes the incalculable and common array of ‘cash in hand’ payments. The size of this ‘informal economy’ is impossible to measure. It’s guessed the ‘grey economy’ in ‘developing countries’ is about 40% of their official GDP. In some nations it’s the largest sector of the economy. In ‘developed countries’ it’s said to be around 20% of GDP. There’s also ‘shadow banking’ – which includes financial institutions not subject to ‘regulatory oversight’, as well as the unregulated activities of supposedly ‘regulated’ institutions. The size of this part of the global economy has been estimated at $20 trillion. Then there’s the so-called ‘black economy’, which is also immeasurable. You only have to consider a part of it, illegal drugs, thought to be about 1% of total global trade, to grasp the importance of this economy.

As well, any story about the hidden or ‘black’ economies should acknowledge the open secret that ‘behind every great fortune is a great crime’. Anyone familiar with the development of capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism will have an appreciation of how they were founded on the theft of land and property, the plundering of environments, horrendous violence, cheating, swindling, the enslavement of millions, the robbery of people’s lives and freedom. And this history, written in blood, hasn’t ended.

In another blog post, The Last Delegation, I wrote about the rise of the new bourgeois in Russia during the 1990s. As the Soviet Union disintegrated, traditional crime areas, such as robbery, illegal drugs, gambling and prostitution, were thriving and those able to were enriching themselves. The black market ‘mafia’ were making off with whatever they could get their hands on, while cunning members of the ruling elite were using their privileges to become richer and to secure their futures. The up-and-coming oligarchs emerged as well-connected entrepreneurs, getting rich through connections to business or political networks, as they plundered state resources and robbed the populace as part of the new ‘free market’ economy.

A poster I bought in Moscow in 1990 reads; ‘Shadowy economics, corruption and criminality – woven in an organised manner. We have to organise to squash and untangle them and pull them out by the roots!’

During this period, as James Petras explains; “Over a hundred billion dollars a year was laundered by the mafia oligarchs in the principal banks of New York, London, Switzerland, Israel and elsewhere – funds which would later be recycled in the purchase of expensive real estate in the USA, England, Spain, France as well as investments in British football teams, Israeli banks and joint ventures in minerals.” The winners of the Russian gang wars “followed up by expanding operations to a variety of new economic sectors, investments in the expansion of existing facilities (especially in real estate, extractive and consumer industries) and overseas. Under President Putin, the gangster-oligarchs consolidated and expanded – from multi-millionaires to billionaires, to multi-billionaires. From young swaggering thugs and local swindlers, they became the ‘respectable’ partners of American and European multinational corporations”, as they continued to ‘diversify’ into stock speculation, banking, finance and company buyouts. Petras details a similar process with the rise of the ‘new bourgeois’ in China, Brazil, Mexico, India, and more. Many others have investigated the legal and illegal crimes of the ruling class in different parts of the world.

What can we believe in . . . ?

For those who’ve managed to read up to this point, you may be asking – how long does this story go for? While many people across the globe are saying; ‘What can we believe in?’ ‘There’s nothing we can trust anymore’.

It’s not surprising that numerous pundits now believe ‘extend and pretend’ is a confidence trick whose days are numbered. Systemic collapse has been forestalled by government cuts, intervention, bailouts, stimulus packages, interest rate and currency manipulation, and so on, seeking to guarantee future profits. Yet, the continuing refusal of people to pay their debts, to accept austerity, and to work harder for less, (along with the vicious battles between different capitalist gangs and the ruins left in their wake) sees fictitious capital continually expand, a range of economic, political, environmental and social crises intensify, the system’s crimes become more apparent, and claims of growth and recovery revealed as fantasies.

Throughout The Big Short there’s a consideration of value – of what things are really worth. The movie appears to centre on the value of money, stocks, houses, superannuation, pensions, wages, salaries, and dividends, as this is what people are often preoccupied with when worrying about financial crisis. Yet behind these concerns are deeper questions about what we value and how we value. How do we value life? How do we value each other? What are our relationships worth? How can we treasure the environment? How long can we put off making difficult decisions – seeking to avoid harsh realities? Are we reaching the conclusion of ‘extend and pretend’?

The future is unwritten . . .

Nick Southall

Punk: ‘Don’t be told want you want, Don’t be told what you need!’

Posted: February 2, 2016 in UncategorizedPunk – prostitute, queer, beginner, worthless person, youth, petty criminal, inspired by punk rock, a style or movement characterised by the adoption of aggressively unconventional and often bizarre or shocking clothing, hairstyles, etc., and the defiance of social norms.

During the late 1970’s and through the 1980’s, the Illawarra region of New South Wales felt the impact of major economic restructuring, mass sackings and unemployment. Thousands were forced from their jobs and many youth faced ‘no future’. As unemployment and poverty in the city of Wollongong grew, so did a new youth culture – punk. Punk exploded into popular consciousness with the Sex Pistols, their 1977 hit single ‘God Save the Queen’ and their album ‘Never Mind the Bollocks’. The Pistol’s ‘Anarchy in the UK’ tour of England with The Clash made both bands infamous, as city after city banned their gigs and conservative politicians and media commentators denounced them. The Pistols and The Clash were strongly influenced by revolutionary politics and their anti-authoritarian, anarchic spit in the face of the establishment struck a powerful chord among marginalised youth, not just in Britain, but also in far-away Wollongong.

Today, it’s hard to appreciate how incendiary punk was at this time of intensifying economic, political and social crisis. For both supporters and opponents it was like throwing a match into a tinderbox. ‘God Save the Queen’ was banned by the BBC and the U.K. Independent Broadcasting Authority. It’s widely believed the song was considered so inflammatory that the BBC and the British Phonographic Institute refused to allow it to reach number one. None-the-less, it was officially number two on the charts during the week that marked 25 years since the Queen’s coronation. Described by the contemporary BBC as “a clarion call for dispossessed youth . . . its energy and sense of dissatisfaction sum up perfectly what it felt like to be young and alienated in 1977.”

With my parents and younger brother, I spent six months in England during 1977. Returning to the old country, after three years in Australia, ‘a sense of dissatisfaction’ is a serious understatement of how I felt. Rather than finding an idealised past that never really existed, the U.K. was instead miserable and depressed. Thatcherism and the National Front were on the rise. The intimidating presence of ‘boot boys’ and ‘boot girls’ personified the violent reality of widespread poverty, crisis and decline. There was little escape from the sense of foreboding, that something even more brutal was coming. ‘No future.’

The idea that young people had ‘no future’ became increasingly common, and back in Australia in 1978, at the age of sixteen, I thought ‘fuck this shit’, fled Wollongong High school, and went on the dole. I was miserable, frustrated and angry. Punk offered me a way of breaking out of what I experienced as the suffocating living death of mainstream society and of connecting with other people who were rebellious. I was pissed off about my own situation, being a high school drop-out, poor, and unemployed, and I was enraged about the state of society. I wanted to revolt, rise up with other people who were sick of the way things were, and change the world. Punk felt powerful, dangerous, and to many of those in power it was considered a serious threat to the status quo.

The Ramones were the first overseas punk band I saw perform live, when they came to Wollongong in 1980. Playing 30 songs in 55 minutes of non-stop, high-energy, fun filled rock, they had those packed into Wollongong Leagues Club frantically pogoing up and down on the spot until exhausted. The Clash was my favourite band, because they combined punk music with serious political messages, while campaigning against war, racism, and Nazis. They toured Australia in 1982 and I used most of my fortnightly dole money on tickets for my then girlfriend Chris and myself. Much of my remaining cash covered our train fares to Sydney to see the band play at the Capitol Theatre. Attending the concert was our Valentine’s Day treat and we loved it. The whole gig was amazing and at the half-way mark an Indigenous activist gave a rousing speech.

As a young punk I was excited about the politicisation of music and youth culture, while being concerned about the contradictions of punk; the degeneration of bands like the Sex Pistols, the scene’s commercialisation, and whether punk would be reduced to a spectacle. A review of the first Clash gig in Sydney described the experience of a local punk friend of mine while he queued to get inside – “On the other side of Campbell Street, the cops are climbing out of their cars. As they emerge, a few sneers and jeers celebrate their arrival. Crossing the road, the cops move into the crowd and single out a few punks. Wrestling them back to the cars, they slam them into the bonnets, restraining them before loading them into the paddy wagons. In their second floor dressing room, oblivious to the scenes outside, the Clash are preparing to take to the stage. As the first of the paddy wagons pulls out, the kids in the back claw at the grill, screaming “Riot! Riot!” Nobody leaves the queue. The driver deliberately slams his brakes hard, sending bodies careering across the back of the van. And then he changes gears and drives off. The rest of the cops pull out as quickly as they’d arrived. As a tactical show of strength, the exercise has been successful.”

Of the other main punk bands around at this time, I especially enjoyed the Dead Kennedys and Crass, who attempted to push the militant politics of punk to their limits. I missed out on seeing the Dead Kennedy’s when they toured in 1983 as I was broke and couldn’t manage to sneak into their gig. But, from the same year, I still have my copy of Crass’s most infamous single ‘How Does It Feel To Be The Mother of 1,000 Dead?’, described by a Daily Mirror columnist as “the most revolting and unnecessary record I have ever heard” and “a vicious and obscene attack on Margaret Thatcher’s motives for engaging in the Falklands war.” The band sold tens of thousands of the record, produced on their own independent label, making it the number one indie song in the UK. Soon questions about the band were being raised in the British Parliament and a Government MP attempted to prosecute them under the U.K.’s Obscene Publications Act.

Wollongong’s punk scene began in the later part of the 1970s. It grew out of other local alternative anti-establishment subcultures, as well as the influence of the U.K. and U.S. punk scenes. Wollongong punks borrowed aspects of overseas punk’s music, dress, behaviour and attitudes and added to them with their own styles. Our punk inspired bands incorporated local social influences and addressed local issues, mixing with various alternative subcultures more so than in many other places. In Sydney, punks, mods and skinheads tended to stay apart and would often fight each other. Here in Wollongong there weren’t that many of us; so we tended to stick together for protection and solidarity.

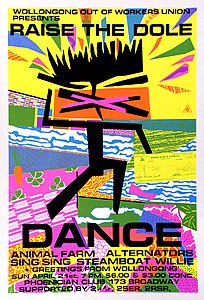

At first, punks mostly hung out at the Wollongong Hotel or the Oxford pub – the Pox, as we called it, was the underage pub, where kids could go and get drunk without being hassled about their age. It was also a place where drugs were easily accessible, it had an outlaw culture, and at times they’d be alternative bands performing. Then we began attending ACME music co-op’s monthly gigs, at the Ironworkers’ Club on Crown Street. These were organised by a collective of local alternative musicians, for local bands who had nowhere else to play, and for people who weren’t into the usual pub bands. The same venue was used for ‘Revolution Rock’ gigs and later by the Wollongong Out of Workers’ Union (WOW) for benefit concerts featuring punk, skinhead, and new wave bands. It was here that local bands like Visitor, Sunday Painters, Nik Nok Nar, Young Home Buyers, the Rezistors and the Alternators got their early gigs and where local punks could hang out together with little fear of being beaten up. The university was another locus of youthful rebellion and Thursday night gigs at the Uni Bar were a popular haunt for punks and new wave music fans.

For most punks the idea of D.I.Y., having your own style, rebelling against and rejecting established conventions and behaviours was the key to being punk. It was a culture for poor people who couldn’t afford to buy a lot of stuff and for those who rejected the glossy mass produced crap that was usually on offer. Most local punks were unemployed or low paid workers and collectively they created their own culture as an assertion of social realism against superficiality. They formed bands, organised gigs, put out records, designed posters, and made their own clothes. Punk was a critique of the dominant culture and consumerism, an expose and subversion of the music industry, and a rejection of commercialism and elitism. You didn’t have to play or sing well, have flash clothes, or expensive equipment, and punk tended to break down the separation of band and audience.

Thanks to the cultural empowerment set off by punk the audience one week could form bands and be playing the next week. Punk’s message was – you can try anything – and what you do, what you create, doesn’t have to be done well, or be perfect, just give it a go. This was the message that inspired me to have a go at playing an instrument, to help form the Alternators (the idea with this band being that the members would alternate and we would also alternate what we did in the band), to help write lyrics for songs (such as C.A.P.I.T.A.L.) and deliver some political spoken word to the band’s free form accompaniment. We also helped to organise political benefit gigs with bands like Mutant Death from Sydney, who released a single called Priority One: Pigs Bum, criticising the Federal Governments employment policies. The song used cut-up excerpts from a fiery on-air exchange between Prime Minister Bob Hawke and myself recorded during a special nationwide radio talk-back on youth issues.

At this time, Wollongong was a very masculine society, still steeped in traditionalist blue collar values. As part of the punk revolution, and reflecting the growth and power of contemporary radical feminism, punk challenged traditional women’s roles in popular music. Punk women flouted musical and social conventions, often by being tough, aggressive, disobedient, rude, and by making themselves look ‘slutty’ or ‘ugly’ and confrontational. The first record my girlfriend Chris and I bought together, which we considered our relationship’s theme song, was the anthemic call for liberation written by female punk icon Poly Styrene and performed by her and the X-Ray Spex.

Wollongong has a long history of militant class struggle, which has created a strong sense of community and spawned a high level of social activism focused on the problems of the working poor and the unemployed. So, it’s no surprise that Wollongong’s punk scene was often overtly political and anti-capitalist. Here the individual and collective manifestations of punk were intertwined from the start. As joblessness grew and political struggles around unemployment swept the city, punk’s focus on ‘do it yourself’ rebellion, individual autonomy, and rejection of capitalist consumption, increasingly mixed with more traditional class struggle.

Unemployed people, many of whom were young punks, established their own union, the Wollongong Out of Workers’ Union (WOW). Some of us had previously been involved in punk graffiti group YAPO (Young and Pissed Off) and for many years one of my YAPO contributions remained sprayed on the walls outside the Wollongong Social Security office – ‘Make BHP Pay!’

As a founding member of WOW, I was keen to see the Union take radical action and confront those in power. Happily I wasn’t alone. Soon after being established, WOW members broke into and squatted a house in Market Street directly opposite the Department of Social Security. Along with about twenty other WOW members I made this my home. With community support, the house became the Union’s offices for the next six years.

For many years, WOW had a high and fairly positive public profile, despite often being seen as a ‘bunch of punks’. As a union of the unemployed, WOW embraced a wide variety of ‘outlaw’ cultures and Union members included petty criminals, drug addicts, prostitutes and the mentally ill, contributing to our notoriety. The ideology and practice of many of WOW’s most active members was a combination of contemporary street level punk, communist and anarchist culture and philosophy. While campaigning against unemployment and for job creation, WOW’s militant struggles and D.I.Y. projects gave people a sense they were contributing to creating a better society outside the realm of wage-labour. Reflecting punk’s rejection of capitalist exploitation and alienation, some WOW members’ were uninterested in traditional work, seeking other ways to make our labour socially useful, aiming to take control of our own lives and give them alternative purposes and meanings.

WOW members with the Union’s Log of Claims outside Federal Parliament in 1983.

WOW members with the Union’s Log of Claims outside Federal Parliament in 1983.

To a large extent, punk culture in WOW was a way of separating ourselves from the rest of society, of showing our difference, while at the same time having something, apart from poverty and unemployment, in common with each other. It was a way of demonstrating our rejection of society in a very visual way. Regardless of what we were doing, even if we were just walking down the street, people could see we were anti-establishment. Punk was both a response to, and a dramatisation of, increasing crisis, unemployment and poverty. Punks dressed confrontationally, presenting themselves as anarchic proletarian ‘degenerates’ and outcasts, spectacles of aggression, frustration and anxiety, at war with capitalist culture.

My own punk style, at various times, included wearing an army jacket with red insignia and communist badges, a padlocked chain around my neck, dyed scarlet hair, a razor blade necklace, torn up, blood splattered, local and overseas punk band T-shirts, ripped and dirty stove pipe jeans rolled up to expose cherry red doc marten boots, and large safety pins as earrings, pushed through my ears while I was high on pain killers. Other members of WOW sported similar get-ups, studded leather jackets, ripped and patched op-shop clothing, studded belts and bracelets, pieces of clothing held together with safety pins, suit jackets, flannelette shirts, a range of boots, patches, badges, hair colours, spiked, shaved haircuts and sculpted mohawks. Many, displayed various forms of self-harm, slashed arms, bruises and signs of neglect.

WOW’s punk culture was the clearest manifestation of some of its member’s rejection of the traditional role of workers, to do waged work, as they attempted to sabotage themselves as commodities. Many WOW members defined themselves against the conservative sections of the union movement and developed an oppositional culture and alternative value systems. There were debates and discussions within WOW about the impact of punk and the effect it was having on our relationship with the general community. Concern was expressed, within the Union, that punk was an obstacle to developing ‘working class unity and co-operation’, recognising that punk and work refusal were a rejection of labour movement traditions based on ideas of the ‘dignity of labour’. But those in WOW who attempted to curb its punk image found themselves in a minority.

Being involved in punk and being involved in WOW was thrilling. You just had to be around the punk scene and the Union’s members to feel the excitement and energy. Both punk and WOW helped young people feel like they could do all the things they wanted to do, that anything was possible. They both changed the way we felt about ourselves and the world around us. We didn’t have to wait around for things to happen, or just be passive victims, we could fight back, sweep the past aside, and create our own way of life. In response to the prediction of ‘No future’, we constructed our own futures, while hoping that time was on our side. It felt as if we had the power to create radical social change – we just had to use it.

Thirty seven years ago, in 1979, I bought a compilation album of punk and ‘new wave’ songs, which included the Mekons’ song ‘Where Were You?’ On New Year’s Eve 2015/2016, some of my younger punk friends released a CD which includes a wonderful cover version of the same song. As if this wasn’t glorious enough, they also released a video for the song which features the dancing son of some other younger punk friends. The future is now and punks not dead!

Nick Southall

Sources

Callaghan, M., & Southall, N., 1985, WOW Dance, Redback Graphix, Wollongong.

Callaghan, M., & Pusell, S., 1984, Raise the Dole Dance, Redback Graphix, Wollongong.

Clash gig review, 1982, Rock Australia Magazine, Sydney.

Dilemas, 2015, Where were you?, YNTPM Records, https://dilemmasdilemmas.bandcamp.com/releases

Hebdige, D., 2003, Subculture: The Meaning of Style, Routledge, London.

Pusell, S., 1983, WOW members with the Union’s Log of Claims, Wollongong.

Pusell, S, & Donarski, C., 1984, What Shall I Wear Tonight?, Wollongong.

Savage, J., 1991, England’s Dreaming; Sex Pistols and Punk Rock, Faber and Faber, London.

Regular readers of Revolts Now will know that I occasionally write about the use of love in advertising. In my post Advertising Love I discuss how every year we see debates about the meaning of Christmas and its increasing commercialisation. For many people Christmas is less about celebrating the birth of Jesus, or giving and receiving presents, and more about love actually (and Love Actually). Yet, many of us feel the tensions of the festive season, when we try to enjoy some time with family, friends and loved ones, only to find ourselves stressed and unhappy. Christmas is both touted and appreciated as a time of celebration, joy, sharing, communing, caring, happiness and hope. It’s also understood and experienced as a time of mourning, over-consumption, grief, loneliness, sadness and regret.

I’m interested in love as an economic, social and political power and how advertising demonstrates both the importance of love to people and to capital; how commercials express, subvert, co-opt, harness and exploit love. Today many commodities are marketed as a way of giving or gaining love, or of showing that we care. The purchase of some product, we are told, will make us loved or demonstrate our love for others.

Love can be deployed as a constructive tool and utilised in destructive ways. Last month, following the attacks in Paris, I wrote about the importance of love in countering terror and war. A few weeks later, as much of the world again focused on Paris, to see how bad the outcome of the United Nations Climate Change Conference would be, those seeking to thwart a more progressive environmental agenda demonstrated how limited perceptions of love, and general anxieties about people’s commitment to each other, can be harnessed to sell romantic corporate illusions of a green future.

SADLY THE VIDEO PREVIOUSLY POSTED HERE APPEARS TO HAVE BEEN REMOVED BY SHELL CORPORATION.

This year, for the first time, my youngest daughter is spending Christmas away from home, in the UK. As she prepares for a Christmas of festive knitted jumpers and the possibility of snow (even though December temperatures in London have been warmer than July’s), she may have seen this popular British Christmas ad, for the John Lewis department stores, highlighting the distance many people feel between them, especially at Christmas. It also speaks to more widespread concerns about the planet/society and our desire to reach out to others.

(Having problems viewing this video? It is also available here.)

And perhaps this year’s most popular UK Christmas commercial is ‘Mog’s Christmas Calamity’.

(Having problems viewing this video? It is also available here.)

When such disasters befall people, this scenario is fairly common – their friends, family, neighbours and communities step-in to care and share. To a certain extent the ‘Mogs’ ad is a light-hearted expression of common concerns about the level of poverty in austerity Britain – with its message that ‘Christmas is for sharing’, as part of Sainsbury’s ‘Live Well For Less’ campaign. The company’s ‘Live Well for Less’ website begins by stating; “These are tough times for family budgets, no question about it.” The site also asks – “Do you love sharing stories?” – encouraging customers to upload videos of themselves reading from the book ‘Mog’s Christmas Calamity’ (in order to assist Sainsbury’s marketing campaign) while explaining that; “Telling stories can ignite imaginations and build bonds between parents and children.”

As indicated at the end of the ‘Mogs’ advert, as well as promoting themselves as supporting family and community ties, Sainsbury’s is also sponsoring the charity ‘Save the Children’, reminding us that among the most prominent advertisers at this time of year are the major charities addressing poverty, homelessness, family breakdown, etc. The traditional economic exchange associated with the purchase of a commodity has increasingly moved into a wider range of spheres through the promotion of ‘ethical consumption’, solidarity, care and love. Attempts by apparently socially concerned or social justice-oriented businesses to reconfigure purchasing as a communal act, and positioning consumer choice as a site of responsibility, are becoming more common in today’s marketplace, as states promote ‘self-reliance’ and corporations seek to position themselves as interested in, and committed to, love.

Sainsbury’s 2014 Christmas ad won a ‘Marketing New Thinking Award’ for ‘Creative Excellence’. The message of this advertisment was “It’s not just about the gifts, it’s about who you share them with.” The commercial re-told the story of Christmas Day 1914 (on its one hundred year anniversary) when British and German soldiers laid down their arms and gathered between the trenches to share greetings and treats, exchange mementos and even play a game of football. Sales of the chocolate bar that featured in the commercial, combined with shopper donations, raised seven million pound for the Royal British Legion charity (supporting military veterans) and helped Sainsbury’s climb into second position in the British grocery sector. I wonder if they would have considered running a similar advert this year, appealing to widespread desires for peace, after the recent decision by the British Parliament to begin bombing Syria?

(Having problems viewing this video? It is also available here.)

In the past few weeks, it’s been interesting to see popular use of the nativity story to highlight the plight of refugees and the need to shelter and support them. This grass roots social media campaign stands in stark contrast to the annual flurry of ‘we can’t celebrate Christmas anymore because of Muslims’ urban myths. Meanwhile, the deceptively self-depreciating and self-aware advert below instead uses the nativity story to portray the commercialisation of Christmas and the love/worship of commodities.

(Having problems viewing this video? It is also available here.)

Clearly it’s not “just a bag” – it’s a powerful symbol. And who doesn’t love a beautiful bag? Even if it only promises short-term gratification and increased status, rather than eternal salvation. Of course, the commercial is humorous because it speaks a certain truth – that Christmas is no longer centred on Jesus, or on each other, but on what we buy.

Michael Hill jewelers are consistent users of love to sell their products, as commodities centred on relationship, displays of wealth, and gift giving. In this advert, from their long-term ‘We’re for Love’ campaign, they declare their commitment to a socially progressive view of love, where ‘everyone gets their fair share’. The commercial stresses that the company’s pieces of jewellery are much more than precious metal and jewels – they are declarations and symbols of love. Here the advertisers disguise the quest for profits with an appreciation of the value of love – highlighting the importance of moving beyond an appeal to individualistic yearnings for economic wealth and status towards collective desires for a diversity of deeper and richer social connections.

(Having problems viewing this video? It is also available here.)

One of the world’s major advertisers, Apple corporation, spends hundreds of millions of dollars a year and employs some of the leading marketeers, psychologists and sociologists just to promote their phones. Consider the sophistication of this Apple Christmas ad, and how it positions the iPhone at the heart of the family.

(Having problems viewing this video? It is also available here.)

The commercial centres on familial love – playing on common concerns about family breakdown, generation gaps and alienated youth, while countering the widespread criticism that smart phones are socially isolating, alienating and debilitating. It achieves its aims by demonstrating how this is may not be the case and in fact the opposite can be true. Having one of the largest advertising budgets in the world, Apple knows that associating itself with creative and positive social relations is their optimum strategy – love sells.

And what would Christmas be without a special song about hope, peace and love? So, this is Apple’s offering for Christmas 2015.

(Having problems viewing this video? It is also available here.)

Clever advertising reflects and mobilises our emotions, our dreams, our fears, and our wishes. The products of Apple’s sweatshop labour can help us create a heart-warming Christmas tune, bring friends and families together, and communicate our common hopes for peace and love. But we are meant to ignore the immense exploitation and destruction of people and the environment involved in the manufacture of the corporation’s merchandise, and who benefits most.

During Christmas we are often faced with important questions about being together, how we spend our time, how we value each other, as well as the nature of the things we consume; their purpose, their fate, their potential, their ability to be something more than profitable commodities, waste, or a means to address fleeting desires. For many people, Christmas is as disappointing as seeking meaning and fulfillment in the accumulation of things. Yet, while the importance of caring relationships can be contrasted to consumerism, they need not be opposed to consumption. People’s love for each other can be facilitated by caring for and about things. These things are not necessarily superficial distractions. But what does it mean to think of the things in our world as more than objects for us to profit from, use and consume – to have deeper encounters with them and to value them in more profound ways?

The distortions imposed on love by the capitalist system shouldn’t prevent us from proclaiming its importance. Loving social relations make our lives worth living despite, against, and beyond capitalism. A communal culture of sharing and caring can rebuild fragile relationships, communities and environments, weaving supportive networks and movements. These networks and movements are produced out of recognition that the widespread hunger and search for love, for meaningful connections to ourselves, to each other, to life, cannot be met by capitalism. Rather than buying into the failed system so widely promoted at Christmas, we can instead find joy, as we share the gift of love.

Nick Southall

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us. (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities)

The city of Wollongong has an Indigenous name, the meaning of which is contested. For tens of thousands of years before white invasion, the people who lived here cared for and helped to shape country. Today, Wollongong is a city of contrasts and contradictions; a beautiful city nestled between the mountains and the sea and blighted by the ugliness of heavy industry and pollution; a city of wealth and poverty; of over-work and mass unemployment. During the past century Wollongong has been a steel and coal city and a progressive city with a rich multicultural history. For much of this period, Australia’s biggest company, Broken Hill Proprietary Company (BHP), was the major employer, wielding significant political and economic power. Its steelworks and mines marked the landscape and its rhythms of industrial society were central to the Illawarra region. The predominance of an industrial workforce, many of whom were employed by a single employer, also helped to create a strong class consciousness. As well, the region has a long history of social activism, the most powerful and influential collective expression of which has been the labour movement.

The Bloodhouse

The depression of the 1930’s saw a massive program of industrial expansion at the Port Kembla steelworks and unemployed people made homes out of the discarded packing cases in which the new equipment had arrived from England. A large shanty town grew up in the shadow of the works. Hungry men would gather around the gates desperate for work, waiting for the whistle to blow. The sounding of the whistle meant that somebody inside the plant had been injured, or perhaps killed. So there would be a new job available. By the time the victim’s blood had been washed away, the replacement would be on the job. Consequently, the steelworks became known as ‘the Bloodhouse’.

The maiming and killing of steelworkers was still a regular occurrence when a short film about the steelworks, The Bloodhouse, was released in 1976. The film highlights how the steelwork’s management sacrificed workers bodies and lives while pumping out pollution and propaganda “designed to get more for nothing out of the pockets of Australia’s working people.” While detailing the exploitation and environmental damage caused by BHP, the film also focuses on the treatment of migrant labour, and includes criticism of the steel industry’s ‘tamed’ right wing ‘grouper trade unions’.

During the 1940s, the Federated Ironworkers’ Association FIA (the largest steel union and now part of the Australian Workers Union) was organised by the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) under the leadership of Ernie Thorton. CPA member, Jack McPhillips, was elected national secretary of the Union in 1950. After being jailed twice for his union activities, Jack was defeated in his position by the anti-communist ‘industrial groupers’ in 1952. In these ‘red scare’ years, anti-communists took control of many unions. During the 1960s, the CPA and other communists played key roles in establishing FIA Rank & File organisations to oppose the right-wing Short/Hurrell leadership. In 1972, the ‘Rank & File’ ticket won the FIA Port Kembla branch elections with Nando Lelli, an Italian migrant steelworker and a ‘friend of the CPA’, becoming the branch secretary. This broke the national dominance of the hard right in the FIA. However, the Port Kembla branch remained an isolated ‘red’ branch for many years and had to constantly struggle against being sabotaged by the national leadership.

By the later part of the 1970s, after years of determined and often bitter struggle, the workforce in the Illawarra steel industry was increasingly militant and had gained relatively advanced wages and conditions. None-the-less, the steelworks continued to damage workers, the environment, and the community. For example, during the recent past, there has been a great deal of attention given to cancer clusters among workers and nearby residents. The steelworks is Australia’s number one producer of the highly toxic chemical dioxin. Dioxin is a carcinogenic by-product of steel making that affects body organs, the immune system and the reproductive system. The most minute exposure to dioxin during the gestation period can leave unborn children with a reduced immune system. The house I lived in, during the 1980s, was just down the street from the steelworks. So, when the south-easterly winds blew, my family and I were right in the path of its pollution, regularly exposing us to dioxin and a range of other chemicals. After my eldest daughter was diagnosed with Rheumatoid Arthritis at the age of nine, we wondered – Are these chemicals responsible for her malfunctioning immune system? Is it because of them she couldn’t open a door, brush her hair, dress herself, or walk upstairs without pain?

Learning to Labour

Come all students of High,

Hail to the black and the green,

Proudly shall our flag fly,

Flag of the emerald sheen,

Black for the coal that gives life to our mills,

Green for the meadows that slope to our hills,

Let your voice ring as we joyfully sing,

Wollongong High School are we!

(Wollongong High School Song)

In 1978, at the age of sixteen, I fled Wollongong High school and went on the dole. I joined the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) and became a full-time cadre, working at the Party’s bookshop in Lowden Square, operating the Party’s offset press and becoming active in a range of local organisations and campaigns.

During this time, the Illawarra had elected left-wing ALP Members to both State and Federal Parliament and the most powerful and influential local unions were led by ALP members committed to their party’s ‘socialist objective’ and/or by CPA members committed to a not dissimilar reformist party program. The Communist Party was well respected among broad sections of workers, giving it significant influence beyond the size of its membership. CPA members and sympathisers were in leading positions in the coal, steel, waterside, and other unions. Party member Merv Nixon was the long-standing secretary of the South Coast Labour Council, the peak regional trade union body and hence also a member of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) executive.

After working for ‘the Party’ for a year, some senior comrades encouraged me to apply for a job in the steelworks or the pits. CPA cadre on the shop floor were highly respected and the Party was keen to replenish its number of rank-and-file activists. Although it was difficult to get work in either industry, as ‘the company books’ were now closed and the era of mass sackings was about to begin, strings could be pulled and a position would be found for me. This was considered a generous offer and a sign of respect for my work. However, I was a young punk and my favourite band’s lyrics were ringing in my ear.

Face front you got the future shining,

Like a piece of gold,

But I swear as we get closer,

It looks more like a lump of coal,

But it’s better than some factory,

Now that’s no place to waste your youth,

I worked there for a week once,

I luckily got the boot.

(All the Young Punks, The Clash)

Instead, I became active in the unemployed people’s movement via various local attempts to create a union of the unemployed. This was a decision I was able to make thanks to the support of my comrades, friends and family. At the same time, many others were fighting for jobs in the steel industry (e.g. Jobs for Women campaign) and soon mass retrenchments began in both the coal and steel industries.

Through the 1980’s, the Illawarra felt the impact of major economic and technological change, as capital relentlessly attacked organised labour and deliberately targeted areas of worker’s militancy for ‘restructuring’. Mass sackings, unemployment, poverty and social crisis gripped the region. At the start of the 1980s, twenty five thousand people worked for BHP Steel and thousands more worked in the local mines. The sackings of the 1980s would see the closure of three quarters of the pits and the destruction of thousands of steelworker’s jobs. Over a number of years the steelworks’ workforce was slashed to five thousand.

Wollongong’s unemployment crisis brought out a collective response as the city’s people turned outwards in anger and protest. This included the infamous Kemira stay-in strike, the storming of Federal P arliament by Wollongong workers, the Right to Work march from Wollongong to Sydney and the formation of the Wollongong out of Workers’ Union. The militant actions of Wollongong workers played an important part in bringing down the Fraser Government and in the election of the Hawke Government in 1983 (for more on this period see Working for the Class).

arliament by Wollongong workers, the Right to Work march from Wollongong to Sydney and the formation of the Wollongong out of Workers’ Union. The militant actions of Wollongong workers played an important part in bringing down the Fraser Government and in the election of the Hawke Government in 1983 (for more on this period see Working for the Class).

ALP/ACTU Accord

Leading up to the 1983 Federal Election, it was argued by BHP and its supporters that if the Government and workers weren’t willing to make significant sacrifices the Port Kembla steelworks faced imminent closure. When the ALP Government was elected it had secured an Accord with the ACTU. In Wollongong, the nature of the Accord process was made evident with the implementation of the Government’s Steel Industry Plan. Here the ALP and the ACTU accepted BHP’s long-term strategy and supported the provision of hundreds of millions of taxpayers’ dollars to the company to invest in job-displacing technology. The Steel Industry Plan was rejected by local unions when they were told what it entailed. They argued that BHP was using the ‘steel crisis’ to achieve long-standing objectives of rationalisation and restructure. But as the steelworks’ general manager pointed out at the time – “there is nothing like the contemplation of the hangman in the morning to get people to co-operate.”

During the Hawke government years, the left ALP/CPA alliance was cemented through the Accord process. The CPA worked very closely with the ALP, promoting and policing the Accord, and had soon liquidated itself. The deepening of the Accord process, and the Hawke government’s implementation of neoliberalism, led to increasing tension between those involved in unemployed people’s unions and many of the labour organisations backing us. Unemployed people were excluded from the Accord yet we were expected to support a strategy that would result in cuts in real wages, attacks on the social wage, and continuing sackings.

As unemployed unions continued to resist the Accord’s corporatist strategy, they were increasingly deserted by sections of their previous support base. At the same time, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) decided to classify people trying to help organise the unemployed, as subversives. As trade union power and support for the organised unemployed receded, the federal government intensified its crackdown on unemployed unions. In 1987, the government introduced an activities test which was then used to cut the benefits of jobless people attending protests and those active in ‘political’ organisations, since they were deemed not to be ‘actively looking for work’. Faced with growing attacks from the state and withering support from the labour movement, most unemployed unions disbanded.

Today, unemployment in Wollongong is higher than the national average, and nearly one in every two young people are out of work. The average income of Wollongong workers is now significantly less than the NSW average and the lack of local jobs sees twenty five percent of the workforce commute to Sydney each day for work. Many of Wollongong’s unemployed remain economically and socially marginalised, condemned to a life of poverty and insecurity, consigned to the worst public housing estates and subjected to police and Centrelink harassment.

In 2002/2003, BHP demerged its steel operations and renamed them BlueScope Steel. Since then job losses have continued, wages have been cut and production has been increased. Today, the steelwork’s workforce produces around 500,000 tonnes of steel more than the Australian market needs. With the imminent closure of the domestic vehicle production industry, this excess will rise. At the same time, China’s steel production and exports are rapidly increasing. The current global oversupply of steel has already led to thousands of job losses at steelmakers around the world.