Who Is Behind the Trotskyist Conspiracy?

Ilya Budraitskis

November 21, 2014

OpenLeft.ru

Speaking at a meeting of his United People’s Front a couple days ago, Vladimir Putin said, “Trotsky had this [saying]: the movement is everything, the ultimate aim is nothing. We need an ultimate aim.” Eduard Bernstein’s proposition, misquoted and attributed for some reason to Leon Trotsky, is probably the Russian president’s most common rhetorical standby. He has repeated it for many years to audiences of journalists and functionaries while discussing social policy, construction delays at Olympics sites or the dissatisfaction of the so-called creative class. “Democracy is not anarchism and not Trotskyism,” Putin warnedalmost two years ago.

Putin’s anti-Trotskyist invectives do not depend on the context nor are they influenced by his audience, and much less are they veiled threats to the small political groups in Russia today who claim to be heirs of the Fourth International. Putin’s Trotskyism is of a different kind. Its causes are found not in the present but in the past, buried deep in the political unconscious of the last generation of the Soviet nomenklatura.

The strange myth of the Trotskyist conspiracy, which emerged decades ago, in another age and a different country, has experienced a rebirth throughout Putin’s rule. Sensing, apparently, the president’s personal weakness for “Trotskyism,” obliging media and corrupted experts have turned this Trotskyism into an integral part of the grand propaganda style. Until he died, the indefatigable “Trotskyist” Boris Berezovsky spun his nasty web from London. Until he turned into a conservative patriot, the incendiary “Trotskyist” Eduard Limonov seduced young people with extremism. Camouflaged “Trotskyists” from the Bush and, later, the Obama administrations have continued to sow war and color revolutions. Unmasking “Trotskyists” has become such an important ritual that for good luck, as it were, the famous Dmitry Kiselyov decided to launch a new media resource by invoking it. So what is the history of this conspiracy? And what do Trotskyists have to do with it?

Conspiracy theories are always conservative by nature. They do not offer an alternative assessment of events but, constantly tardy, chase behind them, inscribing them after the fact into their own pessimistic reading of history. Thus, in his Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism (1797), the Jesuit priest Augustin Barruel, a pioneer of modern conspiracy theory, situated the French Revolution, which had already taken place, in the catastrophic finale of a grand conspiracy of the Knights Templar against the Church and the Capetian dynasty. Masonic conspiracy theories became truly powerful in the late nineteenth century, when the peak of the Masons’ power had already passed. Finally, the idea of a Jewish conspiracy acquired its final shape in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, fabricated by the tsarist secret police at the turn of the twentieth century, when the power of Jewish finance capital had already been undermined by the rising power of industrial capital. Conspiracy theories have always drawn energy from this distorted link with reality, because the fewer conspirators one could observe in the real world, the more boldly one could endow them with incredible magical powers in the imaginary world.

In keeping with the reactive, belated nature of conspiracy theories, the myth of the Trotskyist conspiracy emerged in the Soviet Union when the Left Opposition, Trotsky’s actual supporters, had long ago been destroyed. Unlike, however, the conspiracies of the past, generated by secret agents and mad men of letters, the foundations of the Trotskyist conspiracy were tidily laid by NKVD investigators. The distorting mirror logic of the Great Terror dictated that, although the “Trotskyists” skillfully concealed themselves, and any person could prove to be one, the conspiracy must necessarily be exposed. An unwritten law of Stalinist socialism was that the truth will out, and this, of course, deprived the conspiracy theory of its telltale aura of mystery.

After Stalin’s death, when the Purges were a thing of the past, and Soviet society had begun to become inhibited and conservative, the conspiracy myth took on more familiar features. The stagnation period, with its general apathy, distrust, and societal depression, was an ideal breeding ground for the conspiracy theory. No one had seen any live Trotskyists long ago, and it was seemingly silly to denounce them, but everyone was well informed about the dangers of Trotskyism.

During meaningless classes on “Party history,” millions of Soviet university students learned about the enemies of socialism, the Trotskyists, who had been vanquished long ago in a showdown. Millions of copies of anti-Trotskyist books were published; by the 1970s, this literature had become a distinct genre with its own canon. Its distinguishing feature was a free-form Trotskyism completely emancipated from any connection with actual, historical Trotskyism.

During meaningless classes on “Party history,” millions of Soviet university students learned about the enemies of socialism, the Trotskyists, who had been vanquished long ago in a showdown. Millions of copies of anti-Trotskyist books were published; by the 1970s, this literature had become a distinct genre with its own canon. Its distinguishing feature was a free-form Trotskyism completely emancipated from any connection with actual, historical Trotskyism.

In fact, the Trotskyism of Soviet propaganda was structurelessness incarnate, a misunderstanding. It was“lifeless schema, sophistry and metaphysics, unprincipled eclecticism, […] crude subjectivism, exaggerated individualism and voluntarism.” Unlike the classic monsters of conspiracy theory, the Masons and the Elders of Zion, the Trotskyists did not run the world. They were failed conspirators: they were always exposed, unless, through their own haste and impulsiveness, they did not manage to expose themselves. In keeping with Stalinist socialist realism, their inept evil deeds caused seizures of Homeric laughter among the people and the Party. And yet, recovering from each shameful defeat, they kept on trying. The Trotskyists had no clear plan for establishing global domination, but without a clear purpose, they were dangerous in their passionate desire to instill chaos in places where harmony, predictability, and order reigned.

In their work, these Trotskyists were guided by the crazed “theory of permanent revolution” (which had nothing in common, substantially, with Trotsky’s theory except the name). Its essence is that the revolution should not have any geographical or time constraints. It has no aims, no end, and no meaning. It raises questions where all questions have long been solved. It instills doubt where all doubts have been resolved long ago. A normal person would never be able to understand anything about this theory except one thing: it was invented to ruin his life.

Mikhail Basmanov, author of the cult book In the Train of Reaction: Trotskyism from the 1930s to the 1970s, quoted above, noted, “Unlike many other political movements that had the opportunity to confirm their ideological and political doctrines through the practice of state-building, Trotskyism has not put forward a positive program of action in any country in all the years of its existence.” It is so destructive, that “with its cosmopolitanism, carried to the point of absurdity, which excludes the possibility of developing national programs, Trotskyism undermines the stances even of its own ‘parties’ in certain countries. […] Trotskyism is entangled in the nets of its own theories.”

It is important that the idea of the Trotskyist conspiracy against practical reason, reality, and stability was never popular in late-Soviet society: it did not grow, like the “blood libel,” from the dark superstitions of the mob. It remained a nightmare for only one segment, the ruling bureaucracy, which transmitted the myth of the senseless and merciless “permanent revolution” to future generations in Party training courses and KGB schools.

The Soviet theory of the Trotskyist conspiracy reflected the subconscious fear of ungovernability on the part of the governing class. Devoid of any personalities, the legend of Trotskyism was something like the “black swan” of “actually existing socialism.”

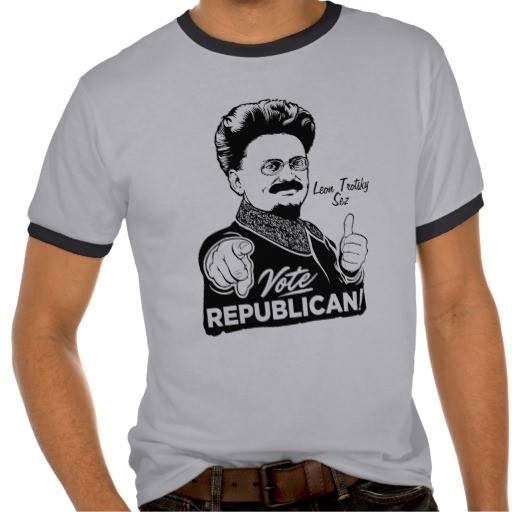

This, by the way, is its fundamental difference from the version of the Trotskyist conspiracy popular among some American conservatives. In America, it is merely one of many varieties of the “minority conspiracy,” a small group of people who have, allegedly, seized power and are implementing their anti-Christian, globalist ideas from the top down. The fact that the anti-Trotskyist conspiracy theory of the so-called paleoconservatives has become popular in recent years among Kremlin experts and political scientists only goes to show that the old Soviet “Trotskyist conspiracy” has suffered a deficit in terms of its reproduction.

When he confuses Bernstein and Bronstein, Vladimir Putin, however, is not unfaithful to the Soviet anti-Trotskyist legend. Yes, “the goal is nothing, the movement is everything.” The chaos generated by the movement is inevitable, as inevitable as time itself. It moves inexorably toward “permanent revolution,” which cannot be completed and with which one cannot negotiate.

In a recent interview, former Kremlin spinmeister Gleb Pavlovsky, while skillfully avoiding the issue of “Trotskyism,” nevertheless had this to say about Putin:

“He has frightened himself. Where should go next? What next? This is a terrible problem in politics, the problem of the second step. He stepped beyond what he was ready for and got lost: where to go now? […] The gap between [the annexation of] Crimea and subsequent actions is quite noticeable. It is obvious that everything afterwards was an improvisation or reaction to other people’s actions. People who are afraid of the future forbid themselves to think about which path to choose. When you have not set achievable goals, you begin to oscillate between two poles: either you do nothing or you get sucked into a colossal conflict.”

The worst thing is that the specter of Trotskyism, as has happened with many other specters in history, is quite capable of materializing. The post-Soviet system has entered a period of crisis, in which the ruling elite has fewer and fewer chances to manage processes “manually.” For the Trotskyist nightmare of the elites to become a reality, there is no need for live Trotskyists. The need for them arises only when hitherto silent and long-suffering forces come to their senses and raise the question of their own aims. But that is a different story.

Ilya Budraitskis is a historian, researcher, and writer.