- go to the top

- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2011 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

Alf Landon

Alfred "Alf" Mossman Landon (September 9, 1887 – October 12, 1987) was an American Republican politician, who served as the 26th Governor of Kansas from 1933–1937. He was best known for being the Republican Party's (GOP) nominee for President of the United States, defeated in a landslide by Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1936 presidential election.

http://wn.com/Alf_Landon -

Armstrong Williams

Armstrong Williams (born February 5, 1959) is an African American political commentator who writes a conservative newspaper column, hosts a nationally syndicated TV program called The Right Side, and hosts a daily radio show. From 2004 to 2007, he co-hosted a daily radio program with Sam Greenfield, broadcast on WWRL 1600 in New York City.

http://wn.com/Armstrong_Williams -

Austan Goolsbee

Austan Dean Goolsbee (born August 18, 1969) is an American economist, currently serving under President Barack Obama as the Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers. Goolsbee is on leave from the University of Chicago where he is the Robert P. Gwinn Professor of Economics at the Booth School of Business.

http://wn.com/Austan_Goolsbee -

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (; born August 4, 1961) is the 44th and current President of the United States. He is the first African American to hold the office. Obama previously served as a United States Senator from Illinois, from January 2005 until he resigned after his election to the presidency in November 2008.

http://wn.com/Barack_Obama -

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson "Bill" Clinton (born William Jefferson Blythe III, August 19, 1946) is the former 42nd President of the United States and served from 1993 to 2001. At 46 he was the third-youngest president. He became president at the end of the Cold War, and was the first baby boomer president. His wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, is currently the United States Secretary of State. Each received a Juris Doctor (J.D.) from Yale Law School.

http://wn.com/Bill_Clinton -

Bob Beauprez

Robert L. "Bob" Beauprez (born September 22, 1948) is an American politician who was a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives, representing the 7th Congressional District of Colorado.

http://wn.com/Bob_Beauprez -

Dean Baker

Dean Baker (b. July 13, 1958) is an American macroeconomist and co-founder of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, with Mark Weisbrot. He previously was a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute and an assistant professor of economics at Bucknell University. He has a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Michigan.

http://wn.com/Dean_Baker -

Dick Cheney

Richard Bruce "Dick" Cheney (born January 30, 1941) served as the 46th Vice President of the United States from 2001 to 2009 under George W. Bush. He briefly served as Acting President of the United States on two occasions during which Bush underwent medical procedures.

http://wn.com/Dick_Cheney -

financier

http://wn.com/financier -

Franco Modigliani

Franco Modigliani (June 18, 1918 – September 25, 2003) was an Italian American economist at the MIT Sloan School of Management and MIT Department of Economics, and winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 1985.

http://wn.com/Franco_Modigliani -

Gary S. Becker

http://wn.com/Gary_S_Becker -

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (; born July 6, 1946, in New Haven, Connecticut) was the 43rd President of the United States, serving from 2001 to 2009, and the 46th Governor of Texas, serving from 1995 to 2000.

http://wn.com/George_W_Bush -

Joseph Stiglitz

Joseph Eugene Stiglitz, ForMemRS (born February 9, 1943) is an American economist and a professor at Columbia University. He is a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) and the John Bates Clark Medal (1979). He is also the former Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of the World Bank. He is known for his critical view of the management of globalization, free-market economists (whom he calls "free market fundamentalists") and some international institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. In 2000, Stiglitz founded the Initiative for Policy Dialogue (IPD), a think tank on international development based at Columbia University. Since 2001, he has been a member of the Columbia faculty, and has held the rank of University Professor since 2003. He also chairs the University of Manchester's Brooks World Poverty Institute and is a member of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences. Professor Stiglitz is also an honorary professor at Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management. Stiglitz is one of the most frequently cited economists in the world.

http://wn.com/Joseph_Stiglitz -

Mark Weisbrot

Mark Weisbrot is an American economist, columnist and co-director, with Dean Baker, of the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) in Washington, D.C. As a commentator, he contributes to publications such as the New York Times, the UK's The Guardian, and Brazil's largest newspaper, Folha de S. Paulo.

http://wn.com/Mark_Weisbrot -

Michael Kinsley

Michael Kinsley (born March 9, 1951) is an American political journalist, commentator, television host, and pundit. Primarily active in print media as both a writer and editor, he also became known to television audiences as a co-host on Crossfire. Kinsley has been a notable participant in the mainstream media's development of online content.

http://wn.com/Michael_Kinsley -

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (July 31, 1912 November 16, 2006) was an American economist, statistician, a professor at the University of Chicago, and the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics. Among scholars, he is best known for his theoretical and empirical research, especially consumption analysis, monetary history and theory, and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy.

http://wn.com/Milton_Friedman -

Paul Krugman

Paul Robin Krugman (; born February 28, 1953) is an American economist, Professor of Economics and International Affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University, Centenary Professor at the London School of Economics, and an op-ed columnist for The New York Times. In 2008, Krugman won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his contributions to New Trade Theory and New Economic Geography. He was voted sixth in a 2005 global poll of the world's top 100 intellectuals by Prospect.

http://wn.com/Paul_Krugman -

Peter Orszag

http://wn.com/Peter_Orszag -

Robert Pozen

Robert C. Pozen (born 1946) is an American financial executive with a strong interest in public policy. He is currently chairman of MFS Investment Management, which manages more than $170 billion in assets for mutual funds and pension plans. He is also a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School.

http://wn.com/Robert_Pozen -

Roy Blunt

Roy D. Blunt (born January 10, 1950) is an American member of Congress from Missouri. He represents in the U.S. House of Representatives, which takes in most of Southwest Missouri, the most conservative part of the state, anchored in the city of Springfield and also includes other cities such as Joplin, Carthage, and Neosho. The district also contains the popular tourist destination of Branson. Blunt was the House Minority Whip during the 110th Congress but announced that he would step down from the position following the results of the 2008 general elections. Blunt is a member of the Republican Party.

http://wn.com/Roy_Blunt -

Scott McClellan

Scott McClellan (born February 14, 1968) is a former White House Press Secretary (2003–06) for President George W. Bush, and author of a controversial #1 New York Times bestseller about the Bush Administration titled What Happened. He replaced Ari Fleischer as press secretary in July 2003 and served until May 10, 2006. McClellan was the longest serving press secretary under George W. Bush.

http://wn.com/Scott_McClellan -

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (22 April 1870 – 21 January 1924) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years (1917–1924), as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a socialist economic system.

http://wn.com/Vladimir_Lenin

-

California

California (pronounced ) is the most populous state in the United States and the third-largest by land area, after Alaska and Texas. California is also the most populous sub-national entity in North America. It's on the U.S. West Coast, bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the west and by the states of Oregon to the north, Nevada to the east, Arizona to the southeast, Baja California, Mexico, to the south. Its 5 largest cities are Los Angeles, San Diego, San Jose, San Francisco, and Long Beach, with Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Jose each having at least 1 million residents. Like many populous states, California's capital, Sacramento is smaller than the state's largest city, Los Angeles. The state is home to the nation's 2nd- and 6th-largest census statistical areas and 8 of the nation's 50 most populous cities. California has a varied climate and geography and a multi-cultural population.

http://wn.com/California -

CalPERS

The '''California Public Employees' Retirement System (CalPERS)''' is an agency in the California executive branch that "manages pension and health benefits for more than 1.6 million California public employees, retirees, and their families". In fiscal year 2007-2008, $10.88 billion was paid in retirement benefits, and in calendar year 2009 it is estimated that over $5.7 billion will be paid in health benefits.

http://wn.com/CalPERS -

Chile

Chile (, in English often pronounced //,), officially the Republic of Chile ( ), is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far south. With Ecuador, it is one of two countries in South America which do not border Brazil. The Pacific coastline of Chile is 6,435 kilometres (4000 mi). Chilean territory includes the Pacific islands of Juan Fernández, Salas y Gómez, Desventuradas and Easter Island. Chile also claims about of Antarctica, although all claims are suspended under the Antarctic Treaty.

http://wn.com/Chile -

Denver, Colorado

http://wn.com/Denver_Colorado -

Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in Lower Manhattan, New York City. It runs east from Broadway to South Street on the East River, through the historical center of the Financial District. It is the first permanent home of the New York Stock Exchange, the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies. Over time, Wall Street became the name of the surrounding geographic neighborhood and also shorthand (or a metonym) for the "influential financial interests" of the American financial industry, which is centered in the New York City area. Anchored by Wall Street, New York City vies with the City of London to be the financial capital of the world.

http://wn.com/Wall_Street

- 401(k)

- 401k

- A.G. Edwards

- AARP

- advertisements

- Alf Landon

- Armstrong Williams

- Austan Goolsbee

- Baby boomers

- bankruptcy

- Barack Obama

- Ben Bernanke

- Bill Clinton

- bipartisan

- birth rate

- Bob Beauprez

- California

- CalPERS

- Cato Institute

- Chile

- Club for Growth

- CNN

- conservatism

- Consumer Price Index

- David C. John

- Dean Baker

- Democracy Now!

- demographics

- Denver, Colorado

- Dick Cheney

- disability

- economics

- economist

- FactCheck

- Federal Reserve

- financier

- Franco Modigliani

- free lunch

- Free to Choose

- Gallup poll

- Gary S. Becker

- George W. Bush

- guerrilla warfare

- Helvering v. Davis

- Heritage Foundation

- House Majority Whip

- Hurricane Katrina

- ideological

- index fund

- inflation

- IOU (debt)

- Joseph Stiglitz

- labor union

- Liberalism

- Libertarianism

- libertarians

- life expectancy

- Los Angeles Times

- mainstream media

- Mark Weisbrot

- Memorial Day

- Michael Kinsley

- Milton Friedman

- moral hazard

- mutual fund

- New York Times

- Nobel Laureate

- Nobel Prize

- Paul Krugman

- PAYGO

- payroll tax

- Pensions crisis

- Peter Orszag

- political capital

- Ponzi scheme

- poverty

- present value

- press conference

- privatization

- Progressive tax

- purchasing power

- Pythonidae

- recess appointment

- regressive tax

- retirement

- Robert Pozen

- Rolling Stone

- Roy Blunt

- S&P; 500

- savings

- Scott McClellan

- Slate.com

- Social security

- steel

- stock market

- The Atlantic

- The New York Times

- The News & Observer

- Treasury security

- U.S. National Debt

- Urban Institute

- USA Next

- USA Today

- Vladimir Lenin

- Wall Street

- white papers

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:07

- Published: 31 Aug 2010

- Uploaded: 20 Oct 2011

- Author: TheYoungTurks

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:10

- Published: 13 Sep 2011

- Uploaded: 26 Sep 2011

- Author: Hollywood2NY

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 18:57

- Published: 22 Feb 2010

- Uploaded: 18 Oct 2011

- Author: catoinstitutevideo

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:52

- Published: 23 Sep 2011

- Uploaded: 20 Oct 2011

- Author: ConservativeBeltway

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 17:41

- Published: 30 May 2011

- Uploaded: 24 Aug 2011

- Author: nologorecords

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:02

- Published: 17 Jun 2008

- Uploaded: 15 Sep 2011

- Author: Veracifier

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 12:22

- Published: 08 Sep 2011

- Uploaded: 22 Sep 2011

- Author: scottemcgrath

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 94:58

- Published: 02 Jan 2011

- Uploaded: 17 Oct 2011

- Author: thefilmarchive

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:13

- Published: 04 Nov 2006

- Uploaded: 13 Oct 2011

- Author: sept11vids

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:28

- Published: 26 Jan 2008

- Uploaded: 04 Oct 2011

- Author: mentormatt8

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:57

- Published: 25 Jan 2008

- Uploaded: 21 Aug 2010

- Author: AllieCaulfield

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:52

- Published: 28 Oct 2008

- Uploaded: 03 Mar 2011

- Author: videoholic1980s

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 12:31

- Published: 08 Sep 2011

- Uploaded: 15 Oct 2011

- Author: MOXNEWSd0tCOM

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 8:50

- Published: 12 Oct 2008

- Uploaded: 27 Sep 2010

- Author: UpTakeVideo

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 11:01

- Published: 25 Jul 2011

- Uploaded: 19 Sep 2011

- Author: politicalarticles

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:08

- Published: 25 Jul 2011

- Uploaded: 11 Aug 2011

- Author: politicalarticles

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:16

- Published: 29 Jul 2011

- Uploaded: 30 Jul 2011

- Author: SpiritofJefferson

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:13

- Published: 12 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 20 Oct 2011

- Author: immicontfla

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:05

- Published: 12 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 19 Sep 2011

- Author: immicontfla

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:31

- Published: 12 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 19 Oct 2011

- Author: immicontfla

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:38

- Published: 12 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 19 Oct 2011

- Author: immicontfla

- 10^12

- 401(k)

- 401k

- A.G. Edwards

- AARP

- advertisements

- Alf Landon

- Armstrong Williams

- Austan Goolsbee

- Baby boomers

- bankruptcy

- Barack Obama

- Ben Bernanke

- Bill Clinton

- bipartisan

- birth rate

- Bob Beauprez

- California

- CalPERS

- Cato Institute

- Chile

- Club for Growth

- CNN

- conservatism

- Consumer Price Index

- David C. John

- Dean Baker

- Democracy Now!

- demographics

- Denver, Colorado

- Dick Cheney

- disability

- economics

- economist

- FactCheck

- Federal Reserve

- financier

- Franco Modigliani

- free lunch

- Free to Choose

- Gallup poll

- Gary S. Becker

- George W. Bush

- guerrilla warfare

- Helvering v. Davis

- Heritage Foundation

- House Majority Whip

- Hurricane Katrina

- ideological

- index fund

- inflation

- IOU (debt)

- Joseph Stiglitz

- labor union

- Liberalism

- Libertarianism

- libertarians

- life expectancy

- Los Angeles Times

- mainstream media

size: 7.5Kb

size: 2.6Kb

size: 3.6Kb

size: 6.2Kb

size: 11.9Kb

size: 12.0Kb

size: 2.7Kb

size: 3.1Kb

size: 4.6Kb

Reform proposals continue to circulate with some urgency, due to a long-term funding challenge faced by the program. Starting in 2015 and continuing thereafter, program expenses are expected to exceed cash revenues. This is due to the aging of the baby-boom generation (resulting in a lower ratio of paying workers to retirees), expected continuing low birth rate (compared to the baby-boom period), and increasing life expectancy. Further, the government has borrowed and spent the accumulated surplus funds, called the Social Security Trust Fund.

During 2011 the Trust Fund held $2.6 trillion, up from $2.5 trillion in 2010. The Trust Fund consists of the savings of worker contributions and associated interest, to be used towards future benefit payments. Funds are held in United States Treasury bonds and U.S. securities backed "by the full faith and credit of the government". The funds borrowed from worker contributions are part of the total national debt of $14.3 trillion as of March 2011. By 2015, the government is expected to have borrowed nearly $3.25 trillion from the Social Security Trust Fund.

Between 2015 and 2037, Social Security has the legal authority to draw amounts from other government tax sources besides the payroll tax, to fully fund the program. However, this will liquidate the Trust Fund during that period. By 2037, the Trust Fund is expected to be officially exhausted, meaning that only the ongoing payroll tax collections thereafter will be available to fund the program. There are certain key implications to understand under current law, if no reforms are implemented: Payroll taxes will only cover 78% of the scheduled payout amounts after 2037. This declines to 75% by 2084. Without changes to the law, Social Security would have no legal authority to draw other government funds to cover the shortfall and payments would decline without a large tax/revenue increase or increase in eligibility age. Between 2015 and 2037, redemption of the trust fund balance to pay retirees will draw approximately $4 trillion in government funds from sources other than payroll taxes. This is a funding challenge for the government overall, not just Social Security. The present value of unfunded obligations under Social Security as of August 2010 was approximately $5.4 trillion. In other words, this amount would have to be set aside today such that the principal and interest would cover the shortfall over the next 75 years. The estimated annual shortfall averages 1.92% of the payroll tax base or 1.0% of gross domestic product. The annual cost of Social Security benefits represented 4.8% of GDP (a measure of the size of the economy) in 2009. This is projected to increase gradually to 6.1% of GDP in 2035 and then decline to about 5.9% of GDP by 2050 and remain at about that level.

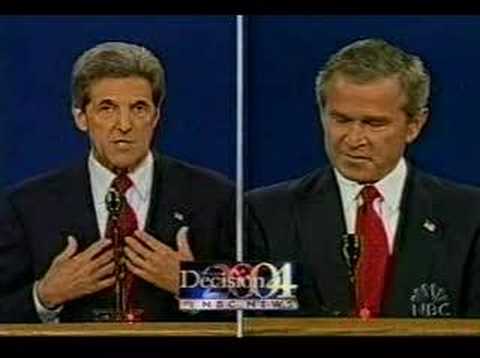

Former President George W. Bush called for a transition to a combination of a government-funded program and personal accounts ("individual accounts" or "private accounts") through partial privatization of the system. President Barack Obama "strongly opposes" privatization or raising the retirement age, but supports raising the cap on the payroll tax ($106,800 in 2009) to help fund the program.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said on October 4, 2006: "Reform of our unsustainable entitlement programs should be a priority." He added, "the imperative to undertake reform earlier rather than later is great." The tax increases or benefit cuts required to maintain the system as it exists under current law are significantly higher the longer such changes are delayed. For example, raising the payroll tax rate to 14.4% during 2009 (from the current 12.4%) or cutting benefits by 13.3% would address the program's budgetary concerns indefinitely; these amounts increase to around 16% and 24% if no changes are made until 2037.

Background on funding challenges

Social Security is funded through the Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax (FICA), a payroll tax. Employers and employees are responsible for making equal FICA contributions. During 2009, Social Security taxes were levied on the first $106,800 of income for employment; amounts earned above that are not taxed. Covered workers are eligible for retirement and disability benefits. If a covered worker dies, his or her spouse and children may receive survivors' benefits. Social Security accounts are not the property of their beneficiary and are used solely to determine benefit levels. Social Security funds are not invested on behalf beneficiaries. Instead, current receipts are used to pay current benefits (the system known as "pay-as-you-go"), as is typical of some insurance and defined-benefit plans.In each year since 1983, tax receipts and interest income have exceeded benefit payments and other expenditures, most recently (in 2009) by more than $120 billion. However, this annual "surplus" is expected to change to a deficit around 2015, when payments begin to exceed receipts and interest thereafter. The fiscal pressures are due to demographic trends, where the number of workers paying into the program continues declining relative to those receiving benefits. The number of workers paying into the program was 5.1 per retiree in 1960; this declined to 3.3 in 2007 and is projected to decline to 2.1 by 2035. Further, life expectancy continues to increase, meaning retirees collect benefits longer. Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke has indicated that the aging of the population is a long-term trend, rather than a proverbial "pig moving through the python."

The accumulated surpluses are invested in special non-marketable Treasury securities (treasuries) issued by the U.S. government, which are deposited in the Social Security Trust Fund. At the end of 2009, the Trust Fund stood at $2.5 trillion. The $2.5 trillion amount owed by the federal government to the Social Security Trust Fund is also a component of the U.S. National Debt, which stood at $13.3 trillion as of August 2009. By 2019, the government is expected to have borrowed nearly $3.8 trillion against the Social Security Trust Fund.

The CBO projected in 2010 that an increase in payroll taxes ranging from 1.6%-2.1% of the payroll tax base, equivalent to 0.6%-0.8% of GDP, would be necessary to put the Social Security program in fiscal balance for the next 75 years. In other words, raising the payroll tax rate to about 14.4% during 2009 (from the current 12.4%) or cutting benefits by 13.3% would address the program's budgetary concerns indefinitely; these amounts increase to around 16% and 24% if no changes are made until 2037. The value of unfunded obligations under Social Security during FY 2009 was approximately $5.4 trillion. In other words, this amount would have to be set aside today such that the principal and interest would cover the shortfall over the next 75 years. Projections of Social Security's solvency are sensitive to assumptions about rates of economic growth and demographic changes.

Because Social Security receipts currently exceed payments, the program also reduces the size of the annual federal budget deficit. For example, the budget deficit would have been $182 billion higher in 2007 (i.e., $344 billion rather than $162 billion published) if Social Security were accounted for separately from the overall budget.

Increasing unemployment due to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008-2010 has significantly reduced the amount of payroll tax income that funds Social Security. Further, the crisis also caused more to apply for both retirement and disability benefits than expected. During 2009, payroll taxes and taxation of benefits resulted in cash revenues of $689.2 billion, while payments totaled $685.8 billion, resulting in a cash surplus (excluding interest) of $3.4 billion. Interest of $118.3 billion meant that the Social Security Trust Fund overall increased by $121.7 billion (i.e., the cash surplus plus interest). The 2009 cash surplus of $3.4 billion was a significant reduction from the $63.9 billion cash surplus of 2008.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities wrote in 2010: "The 75-year Social Security shortfall is about the same size as the cost, over that period, of extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts for the richest 2 percent of Americans (those with incomes above $250,000 a year). Members of Congress cannot simultaneously claim that the tax cuts for people at the top are affordable while the Social Security shortfall constitutes a dire fiscal threat."

Current projections

Income and Cost Rates Under Intermediate Assumptions. Source: 2009 OASDI Trustees Report.]]Projections were made by the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds (OASDI) in their 71st annual report dated May 13, 2011. Expenses exceeded tax receipts in 2010. The trust fund is projected to continue to grow for several years thereafter because of interest income from loans made to the US Treasury.

However, the funds from loans made have been spent along with other revenues in the general funds in satisfying annual budgets. At some point, however, absent any change in the law, the Social Security Administration will finance payment of benefits through the net redemption of the assets in the trust fund. Because those assets consist solely of U.S. government securities, their redemption will represent a call on the federal government's general fund, which for decades has been borrowing the Trust Fund's surplus and applying it to its expenses to partially satisfy budget deficits. To finance such a projected call on the general fund, some combination of increasing taxes, cutting other government spending or programs, selling government assets, or borrowing would be required.

The balances in the trust fund are projected to be depleted either by 2036 (OASDI Trustees' 2011 projection), or by 2038 (Congressional Budget Office's extended-baseline scenario) assuming proper and continuous repayment of the outstanding treasury notes. At that point, under current law, the system's benefits would have to be paid from the FICA tax alone. Revenues from FICA are projected at that point to be continue to cover about 77% of projected Social Security benefits if no change is made to the current tax and benefit schedules.

Framing the debate

Ideological arguments

Ideology plays a major part of framing the Social Security debate. Key points of philosophical debate include, among others:

Retirees and others who receive Social Security benefits have become an important bloc of voters in the United States. Indeed, Social Security has been called "the third rail of American politics" — meaning that any politician sparking fears about cuts in benefits by touching the program endangers his or her political career. The New York Times wrote in January 2009 that Social Security and Medicare "have proved almost sacrosanct in political terms, even as they threaten to grow so large as to be unsustainable in the long run."

Conservative ideological arguments

Conservatives argue that Social Security reduces individual ownership by redistributing wealth from workers to retirees and bypassing the free market. Social Security taxes paid into the system cannot be passed to future generations, as private accounts can, thereby preventing the accumulation of wealth to some degree. Conservatives tend to argue for a fundamental change in the structure of the program. Conservatives also argue that the US Constitution does not permit the Congress to set up a savings plan for retirees (leaving this authority to the states), although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Helvering v. Davis that Congress had this authority.

Liberal ideological arguments

Liberals argue that government has the obligation to provide social insurance, through mandatory participation and broad program coverage. During 2004, Social Security constituted more than half of the income of nearly two-thirds of retired Americans. For one in six, it is their only income. Liberals tend to defend the current program, preferring tax increases and payment modifications.

Pro-privatization arguments

The conservative position is often pro-privatization. There are countries other than the U.S. that have set up individual accounts for individual workers, which allow workers leeway in decisions about the securities in which their accounts are invested, which pay workers after retirement through annuities funded by the individual accounts, and which allow the funds to be inherited by the workers' heirs. Such systems are referred to as 'privatized.' Currently, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Chile are the most frequently cited examples of privatized systems. The experiences of these countries are being debated as part of the current Social Security controversy.In the United States in the late 1990s, privatization found advocates who complained that U.S. workers, paying compulsory payroll taxes into Social Security, were missing out on the high rates of return of the U.S. stock market (the Dow averaged 5.3% compounded annually for the 20th century). They likened their proposed "Private Retirement Accounts" (PRAs) to the popular Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) and 401(k) savings plans. But in the meantime, several conservative and libertarian organizations that considered it a crucial issue, such as the Heritage Foundation and Cato Institute, continued to lobby for some form of Social Security privatization.

Anti-privatization arguments

The liberal position is typically anti-privatization. Those who have taken an anti-privatization position argue several points (among others), including:

Alternate views

Accordingly, advocates of major change in the system generally argue that drastic action is necessary because Social Security is facing a crisis. In his 2005 State of the Union speech, President Bush indicated that Social Security was facing "bankruptcy." In his 2006 State of the Union speech, he described entitlement reform (including Social Security) as a "national challenge" that, if not addressed timely, would "present future Congresses with impossible choices -- staggering tax increases, immense deficits, or deep cuts in every category of spending."

A liberal think tank, The Center for Economic and Policy Research, says that "Social Security is more financially sound today than it has been throughout most of its 69-year history" and that Bush's statement should have no credibility.

Nobel Laureate economist Paul Krugman, deriding what he called "the hype about a Social Security crisis", wrote:

The claims of the probability of future difficulty with the current Social Security system are largely based on the annual analysis made of the system and its prospects and reported by the governors of the Social Security system. While such analysis can never be 100% accurate, it can at least be made using different probable future scenarios and be based on rational assumptions and reach rational conclusions, with the conclusions being no better (in terms of predicting the future) than the assumptions on which the predictions are based. With these predictions in hand, it is possible to make at least some prediction of what the future retirement security of Americans who will rely on Social Security might be. It is worth noting that James Roosevelt, former associate commissioner for Retirement Policy for the Social Security Administration, claims that the "crisis" is more a myth than a fact.

Proponents of the current system argue if and when the trust fund runs out, there will still be the choice of raising taxes or cutting benefits, or both. Advocates of the current system say that the projected deficits in Social Security are identical to the "prescription drug benefit" enacted in 2002. They say that demographic and revenue projections might turn out to be too pessimistic — and that the current health of the economy exceeds the assumptions used by the Social Security Administration.

These Social Security proponents argue that the correct plan is to fix Medicare, which is the largest underfunded entitlement, repeal the 2001–2004 tax cuts, and balance the budget. They believe a growth trendline will emerge from these steps, and the government can alter the Social Security mix of taxes, benefits, benefit adjustments and retirement age to avoid future deficits. The age at which one begins to receive Social Security benefits has been raised several times since the program's inception.

Proposals that keep an entirely government-run system

Robert L. Clark, an economist at North Carolina State University who specializes in aging issues, formerly served as a chairman of a national panel on Social Security's financial status; he has said that future options for Social Security are clear: "You either raise taxes or you cut benefits. There are lots of ways to do both."David Koitz, a 30-year veteran of the Congressional Research Service, echoed these remarks in his 2001 book Seeking Middle Ground on Social Security Reform: "The real choices for resolving the system's problems...require current lawmakers to raise revenue or cut spending--to change the law now to explicitly raise future taxes or constrain future benefits." He discusses the 1983 Social Security amendments that followed the Greenspan Commission's recommendations. It was the Commission's recommendations that provided political cover for both political parties to act. The changes approved by President Reagan in 1983 were phased in over time and included raising the retirement age from 65 to 67, taxation of benefits, cost of living adjustment (COLA) delays, and inclusion of new federal hires in the program. There was a key point during the debate when House members were forced to choose between raising the retirement age or raising future taxes; they chose the former. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan indicated the compromises involved showed that lawmakers could still govern. Koitz cautions against the concept of a free lunch; retirement security cannot be provided without benefit cuts or tax increases.

Various institutions have analyzed different reform alternatives, including the CBO, US News & World Report, the AARP, and the Urban Institute.

CBO study

The CBO reported in July 2010 the effects of a series of policy options on the "actuarial balance" shortfall, which over the 75 year horizon is approximately 0.6% of GDP. On a GDP of $14.5 trillion, this represents approximately $90 billion per year; the dollar amount would grow along with GDP. For example, CBO estimated that raising the payroll tax by two percentage points (from 12.4% to 14.4%) over 20 years would increase annual program revenues by 0.6% of GDP, solving the 75-year shortfall. The effects of different policy alternatives are summarized in the CBO chart included at right, from page IX of its report.

AARP study

Revenue raisers #Raise the cap to 90% of taxable earningsApproximately 39% reduction in shortfall #*PRO: Affects only 6% of taxpayers or top 15% of income.Can be phased in gradually.Not a new tax, restores prior policy. #*CON: It's a tax increase for higher earners. #Increase payroll tax rateEach 0.5% tax rate increase addresses 23% of shortfall. #*PRO: A gradual increase would maintain 75-year solvency. #*CON: A regressive tax increase that adversely affect workers. #Raise taxes on benefits10% reduction in shortfallThis amounts to a reduction in the benefit to high wage earners so the pros and cons are purely subjective. #Preserve tax on estates over $3.5 million27% reduction in shortfall #*PRO: Improves tax progressivity, affects only 1/2 of 1% of all estates. #*CON: Would alter the President Bush's tax-cutting plans. #Extend coverage to newly hired state and local government employees10% reduction in shortfall #*PRO: Makes Social Security universal, with all sharing obligations and benefits. #*CON: State and local governments employees might get less retirement benefits. #Invest 15% of the trust funds in stock and bond index funds10% reduction in shortfall #*PRO: In the most optimistic scenario, the trust would earn higher returns on its investment. #*CON: Since the US government has a debt, this amounts to borrowing money in bonds to invest in the stock market, or margin trading.Cost of transition between $600 billion - $3 trillion.Less likely scenarios involve lower or negative returns.Cost trimmers #Adjust the COLA18% reduction in shortfall #*PRO: Saves money. #*CON: This would set the standard of living afforded by Social Security to the level the individual could achieve at their date of initial benefit.The current plan allows for an increased standard of living based on productivity increases made in the US economy. #Increase normal retirement age to 7036% reduction in shortfall #*PRO: Links retirement more closely to life expectancy and increased worker health since program inception. #*CON: Reduces benefits.Unfair to those forced to retire early but not otherwise eligible for other Social Security benefits. #Progressive Indexing - Index benefits to prices, not wages100% reduction in shortfall #*PRO: Could eliminate shortfall. #*CON: Reduces the growth in scheduled benefits over time.

Urban Institute study

The Urban Institute estimated the effects of alternative solutions during May 2010, along with an estimated program deficit reduction:

President Obama's Fiscal Reform Commission

The co-chairmen of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform issued a draft presentation in November 2010 that estimated the effects of alternative solutions, along with an estimated program deficit reduction:

President Obama's proposals

As of September 14, 2008, Barack Obama indicated preliminary views on Social Security reform. His website indicated that he "will work with members of Congress from both parties to strengthen Social Security and prevent privatization while protecting middle class families from tax increases or benefit cuts. As part of a bipartisan plan that would be phased in over many years, he would ask families making over $250,000 to contribute a bit more to Social Security to keep it sound." He has opposed raising the retirement age, privatization, or cutting benefits.

Cost of living adjustment

The current system sets the initial benefit level based on the retiree's past wages. The benefit level is based on the 35 highest years of earnings. This initial amount is then subject to an annual "Cost of Living Adjustment" or COLA. Recent COLA were 2.3% in 2007, 5.8% in 2008, and zero for 2009-2011.The COLA is computed based on the "Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers" or CPI-W. According to the CBO: "Many analysts believe that the CPI-W overstates increases in the cost of living because it does not fully account for the fact that consumers generally adjust their spending patterns as some prices change relative to others." However, CBO also reported that: "...CPI-E, an experimental version of the CPI that reflects the purchasing patterns of older people, has been 0.3 percentage points higher than the CPI-W over the past three decades." CBO estimates that reducing the COLA by 0.5% annually from its current computed amount would reduce the 75-year actuarial shortfall by 0.3% of GDP or about 50%. Reducing each year's COLA results in an annual compounding effect, with greater effect on those receiving benefits the longest.

There is disagreement about whether a reduction in the COLA constitutes a "benefit cut"; the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities considers any reduction in future promised benefits to be a "cut." However, others dispute this assertion because under any indexing strategy the actual or nominal amount of Social Security checks would never decrease but could increase at a lesser rate.

Progressive indexing

"Progressive indexing" would lower the COLA or benefit levels for higher wage groups, with no impact or lesser impact on lower-wage groups. The Congressional Research Service reported that:

"Progressive indexing," would index initial benefits for low earners to wage growth (as under current law), index initial benefits for high earners to price growth (resulting in lower projected benefits compared to current-law promised benefits), and index benefits for middle earners to a combination of wage growth and price growth.

President Bush endorsed a version of this approach suggested by financier Robert Pozen, which would mix price and wage indexing in setting the initial benefit level. The "progressive" feature is that the less generous price indexing would be used in greater proportion for retirees with higher incomes. The San Francisco Chronicle gave this explanation:

Under Pozen's plan, which is likely to be significantly altered even if the concept remains in legislation, all workers who earn more than about $25,000 a year would receive some benefit cuts. For example, those who retire in 50 years while earning about $36,500 a year would see their benefits reduced by 20 percent from the benefits promised under the current plan. Those who earn $90,000 — the maximum income in 2005 for payroll taxes — and retire in 2055 would see their benefits cut 37 percent.

As under the current system, all retirees would have their initial benefit amount adjusted periodically for price inflation occurring after their retirement. Thus, the purchasing power of the monthly benefit level would be frozen, rather than increasing by the difference between the (typically higher) CPI-W and (typically lower) CPI-U, a broader measure of inflation.

Adjustments to the payroll tax limit

During 2009, payroll taxes were levied on the first $106,800 of income; earnings above that amount are not taxed. Approximately 6% of the population earns over this amount, which represents approximately 15% of total wage income. Because of this limit, people with higher incomes pay a lower percentage of tax than people with lower incomes; the payroll tax is therefore a regressive tax. President Bush's 2001 advisory board discussed ways that the system could be adjusted. Eliminating the cap would make this a more progressive tax and would reduce or eliminate the projected deficit. A 2001 Social Security advisory board report stated::Making all earnings covered by Social Security subject to the payroll tax beginning in 2002, but retaining the current law limit for benefit computations (in effect removing the link between earnings and benefits at higher earnings levels), would eliminate the deficit. If benefits were to be paid on the additional earnings, 88 percent of the deficit would be eliminated.

Diamond-Orszag Plan

Peter A. Diamond and Peter R. Orszag proposed in their 2005 book Saving Social Security-A Balanced Approach that Social Security be stabilized by various tax and spend adjustments and gradually ending the process by which the general fund has been borrowing from payroll taxes. This requires increased revenues devoted to Social Security. Their plan, as with several other Social Security stabilization plans, relies on gradually increasing the retirement age, raising the ceiling on which people must pay FICA taxes, and slowly increasing the FICA tax rate to a peak of 15% total from the current 12.4%.

Conceptual arguments regarding privatization

Cost of transition and long-term funding concerns

Critics argue that privatizing Social Security does nothing to address the long-term funding concerns. Diverting funds to private accounts would reduce available funds to pay current retirees, requiring significant borrowing. An analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that President Bush's 2005 privatization proposal would add $1 trillion in new federal debt in its first decade of implementation and $3.5 trillion in the decade thereafter. The 2004 Economic Report of the President found that the federal budget deficit would be more than 1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) higher every year for roughly two decades; U.S. GDP in 2008 was $14 trillion. The debt burden for every man, woman, and child would be $32,000 higher after 32 years because of privatization.Privatization proponents counter that the savings to the government would come through a mechanism called a "clawback", where profits from private account investment would be taxed, or a benefit reduction meaning that individuals whose accounts underperformed the market would receive less than current benefit schedules, although, even in this instance, the heirs of those who die early could receive increased benefits even if the accounts underperformed historical returns.

Opponents of privatization also point out that, even conceding for sake of argument that what they call highly optimistic numbers are true, they fail to count what the transition will cost the country as a whole. Gary Thayer, chief economist for A.G. Edwards, has been cited in the mainstream media saying that the cost of privatizing— estimated by some at $1 trillion to $2 trillion— would worsen the federal budget deficit in the short term, and "That's not something I think the credit markets would appreciate." If, as in some plans, the interest expenditure on this debt is recaptured from the private accounts before any gains are available to the workers, then the net benefit could be small or nonexistent. And this is really a key to understanding the debate, because if, on the other hand, a system which mandated investment of all assets in U.S. Treasuries resulted in a positive net recapturing, this would illustrate that the captive nature of the system results in benefits that are lower than if it merely allowed investment in U.S. Treasuries (purported to be the safest investment on Earth).

Current Social Security system advocates claim that when the risks, overhead costs and borrowing costs of any privatization plan are taken together, the result is that such a plan has a lower expected rate of return than "pay as you go" systems. They point out the high overheads of privatized plans in the United Kingdom and Chile.

Rate of return and individual initiative

Even some of those who oppose privatization agree that if current future promises to the current young generation are kept in the future, they will experience a much lower rate of return than past retirees have. Under privatization, each worker's benefit would be the combination of a minimum guaranteed benefit and the return on the private account. The proponents' argument is that projected returns (higher than those individuals currently receive from Social Security) and ownership of the private accounts would allow lower spending on the guaranteed benefit, but possibly without any net loss of income to beneficiaries.Both wholesale and partial privatization pose questions such as: 1) How much added risk will workers bear compared to the risks they face under current system? 2) What are the potential rewards? and 3) What happens at retirement to workers whose privatized risks turn out badly? For workers, privatization would mean smaller Social Security checks, in addition to increased compensation from returns on investments, according to historical precedent. Debate has ensued over the advisability of subjecting workers' retirement money to market risks.

A technical economic argument for privatization is that, without it, the payroll taxes that support Social Security constitute a tax wedge that reduces the supply of labor, like other tax financed government welfare programs. Liberal economists like Peter Orszag and Joseph Stiglitz have argued that Social Security is already perceived as enough of a forced savings program to preclude a reduction in the labor supply. Richard Disney has agreed with this reply, noting that To the extent that pension contributions are perceived as giving individuals rights to future pensions, the behavioral reaction of program participants to contributions will differ from their reactions to other taxes. In fact, they might regard pension contributions as providing an opportunity for retirement saving, in which case contributions should not be deducted [by economists] from household’s earnings and should not be included in the tax wedge. Privatization advocates nonetheless do not believe that social security taxes will be sufficiently regarded as pension contributions as long as they remain legally structured as taxes (as opposed to being contributions to their own private pensions).

To the extent that pension contributions are perceived as giving individuals rights to future pensions, the behavioral reaction of program participants to contributions will differ from their reactions to other taxes. In fact, they might regard pension contributions as providing an opportunity for retirement saving, in which case contributions should not be deducted from household’s earnings and should not be included in the tax wedge.

Supporters of the current system maintain that its combination of low risks and low management costs, along with its social insurance provisions, work well for what the system was designed to provide: a baseline income for citizens derived from savings. From their perspective, the major deficiency of any privatization scheme is risk. Like any private investments, PRAs could fail to produce any return or could produce a lower return than proponents of privatization assert, and could even suffer a reduction in principal.

Advocates of privatization have long criticized Social Security for lower returns than the returns available from other investments, and cite numbers based on historical performance. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, calculates that a 40-year-old male with an income just under $60,000, will contribute $284,360 in payroll taxes to the Social Security trust fund over his working life, and can expect to receive $2,208 per month in return under the current program. They claim that the same 40-year-old male, investing the same $284,360 equally weighted into treasuries and high-grade corporate bonds over his working life, would own a PRA at retirement worth $904,982 which would pay an annuity of up to $7,372 per month (assuming that the dollar volume of such investments would not dilute yields so that they are lower than averages from a period in which no such dilution occurred.) Furthermore, they argue that the "efficiency" of the system should be measured not by costs as a percent of assets, but by returns after expenses (e.g. a 6% return reduced by 2% expenses would be preferable to a 3% return reduced by 1% expenses). Other advocates state that because privatization would increase the wealth of Social Security users, it would contribute to consumer spending, which in turn would cause economic growth.

Supporters of the current system argue that the long-term trend of U.S. securities markets cannot safely be extrapolated forward, because stock prices relative to earnings are already at very high levels by historical standards. They add that an exclusive focus on long-term trends would ignore the increased risks they think privatization would cause. The general upward trend has been punctuated by severe downturns. Critics of privatization point out that workers attempting to retire during any future such downturns, even if they prove to be temporary, will be placed at a severe disadvantage.

Proponents argue that a privatized system would open up new funds for investment in the economy, and would produce real growth. They claim that the treasuries held in the current trust fund are covering consumption rather than investments, and that their value rests solely upon the continued ability of the U.S. government to impose taxes. Michael Kinsley has said that there would be no net new funds for investment, because any money diverted into private accounts would produce a dollar-for-dollar increase in the federal government's borrowing from other sources to cover its general deficit.

Meanwhile, some investment-minded observers among those who do not support privatization, point out potential pitfalls to the trust fund's undiversified portfolio, containing only treasuries. Many of these support the government itself investing the trust fund into other securities, to help boost the system's overall soundness through diversification, in a plan similar to CalPERS in the state of California. Among the proponents of this idea were some members of President Bill Clinton's 1996 Social Security commission that studied the issue; the majority of the group supported partial privatization, and other members put forth the idea that Social Security funds should themselves be invested in the private markets to gain a higher rate of return.

Another criticism of privatization is that while it might theoretically relieve the government of financial responsibility, in practice for every winner from moving risk from the collective to the individual there will be a loser, and the government will be held politically responsible for preventing those losers from slipping into poverty. Proponents of the current system suspect that for the individuals whose risks turn out badly, these same individuals will support political action to raise state benefits, such that the risks such individuals may be willing to take under a privatized system are not without moral hazard.

Role of government

There are also substantive issues that do not involve economics, but rather the role of government. Conservative Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary S. Becker, currently a graduate professor at the University of Chicago, wrote in a February 15, 2005 article that "[privatization] reduce[s] the role of government in determining retirement ages and incomes, and improve[s] government accounting of revenues and spending obligations." He compares the privatization of Social Security to the privatization of the steel industry, citing similar "excellent reasons."

Management costs of private funds

Opponents of privatization also decry the increased management costs that any privatized system will incur. Dishonest schemes can be sold to naive buyers in which pension values are bled through fees and commissions such as happened in the UK in 1988-1993.Since the U.S. system is passively managed — with no specific funds being tied to specific investments within individual accounts, and with the system's surpluses being automatically invested only in treasuries — its management costs are very low.

Advocates of privatization at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, counter that, "Based on existing private pension plans, it appears reasonable to assume that the costs of administering a well-run system of PRAs might be anywhere from a low of roughly 15 basis points (0.15%) to a high of roughly 50 basis points (0.5%)." They also point to the low costs of index funds (funds whose value rises or falls according to a particular financial index), including an S&P; 500 index fund whose management fees run between 8 basis point (0.08%) and 10 basis points (0.10%).

Windfall for Wall Street?

Opponents also claim that privatization will bring a windfall for Wall Street brokerages and mutual fund companies, who will rake in billions of dollars in management fees.Austan Goolsbee at the University of Chicago has written a study, "The Fees of Private Accounts and the Impact of Social Security Privatization on Financial Managers", which calculates that, "Under Plan II of the President's Commission to Strengthen Social Security (CSSS), the net present value (NPV) of such payments would be $940 billion", and, "amounts to about one-quarter (25%) of the NPV of the revenue of the entire financial sector for the next 75 years", and concludes that, "The fees would be the largest windfall gain in American financial history." The Heritage Foundation has produced their own study, written by David C. John, specifically to counter Goolsbee.

Other analysts argue that dangers of a Wall Street windfall of such magnitude are being vastly overstated. Rob Mills, vice-president of the brokerage industry trade group Securities Industry Association, calculated in a report published in December 2004 that the proposed private accounts might generate $39 billion in fees, in NPV terms, over the next 75 years. This amount would represent only 1.2% of the sector's projected NPV revenues of $3.3 trillion over that timeframe. He concludes that privatization is "hardly likely to be a bonanza for Wall Street." At the same time, the watchdogs at FactCheck estimate that the financial management sector will receive only 0.05% and 0.27% of its total revenues from fees on PRAs (personal retirement accounts).

Other privatization proposals

A range of other proposals have been suggested for partial privatization, such as the 7.65% Solution. One, suggested by a number of Republican candidates during the 2000 elections, would set aside an initially small but increasing percentage of each worker's payroll tax into a 'lockbox', which the worker would be allowed to invest in securities. Another eliminated the Social Security payroll tax completely for workers born after a certain date, and allowed workers of different ages different periods of time during which they could opt to not pay the payroll tax, in exchange for a proportional delay in their receipt of payouts.==George W. Bush's privatization proposal== President George W. Bush discussed the "partial privatization" of Social Security since the beginning of his presidency in 2001. But only after winning re-election in 2004 did he begin to invest his "political capital" in pursuing changes in earnest.

In May 2001, he announced establishment of a 16-member bipartisan commission "to study and report specific recommendations to preserve Social Security for seniors while building wealth for younger Americans", with the specific directive that it consider only how to incorporate "individually controlled, voluntary personal retirement accounts". The majority of members serving on Bill Clinton's similar Social Security commission in 1996 had recommended through their own report that partial privatization be implemented. Bush's Commission to Strengthen Social Security (CSSS) issued a report in December 2001 (revised in March 2002), which proposed three alternative plans for partial privatization:

On February 2, 2005, Bush made Social Security a prominent theme of his State of the Union Address. In this speech, which sparked the debate, it was Plan II of CSSS's report that Bush outlined as the starting point for changes in Social Security. He outlined, in general terms, a proposal based on partial privatization. After a phase-in period, workers currently less than 55 years old would have the option to set aside four percentage points of their payroll taxes in individual accounts that could be invested in the private sector, in "a conservative mix of bonds and stock funds". Workers making such a choice might receive larger or smaller benefits than if they had not done so, depending on the performance of the investments they selected.

Although Bush described the Social Security system as "headed for bankruptcy", his proposal would not affect the projected shortfall in Social Security tax receipts. Partial privatization would mean that some workers would pay less into the system's general fund and receive less back from it. Administration officials said that the proposal would have a "net neutral effect" on the system's financial situation, and that Bush would discuss with Congress how to fill the projected shortfall. The Congressional Budget Office had previously analyzed the commission's "Plan II" (the plan most similar to Bush's proposal) and had concluded that the individual accounts would have little or no overall effect on the system's solvency, and that virtually all the savings would come instead from changing the benefits formula.

As illustrated by the CBO analysis, one possible approach to the shortfall would be benefit cuts that would affect all retirees, not just those choosing the private accounts. Bush alluded to this option, mentioning some suggestions that he linked to various former Democratic officeholders. He did not endorse any specific benefit cuts himself, however. He said only, "All these ideas are on the table." He expressed his opposition to any increase in Social Security taxes. Later that month, his press secretary, Scott McClellan, ambiguously characterized raising or eliminating the cap on income subject to the tax as a tax increase that Bush would oppose.

In his speech, Bush did not address the issue of how the system would continue to provide benefits for current and near-future retirees if some of the incoming Social Security tax receipts were to be diverted into private accounts. A few days later, however, Vice-President Dick Cheney stated that the plan would require borrowing $758 billion over the period 2005 to 2014; that estimate has been criticized as being unrealistically low.

On April 28, 2005, Bush held a televised press conference at which he provided additional detail about the proposal he favored. For the first time, he endorsed reducing the benefits that some retirees would receive. He endorsed a plan from Robert Pozen, described below in the section regarding suggestions for Social Security that do not involve privatization.

Although Bush's State of the Union speech left many important aspects of his proposal unspecified, debate began on the basis of the broad outline he had given.

Politics of the dispute over Bush's proposal

The political heat was turned up on the issue since Bush mentioned changing Social Security during the 2004 elections, and since he made it clear in his nationally televised January 2005 speech that he intended to work to partially privatize the system during his second term.To assist the effort, Republican donors were asked after the election to help raise $50 million or more for a campaign in support of the proposal, with contributions expected from such sources as the conservative Club for Growth and the securities industry. In 1983, a Cato Institute paper had noted that privatization would require "mobilizing the various coalitions that stand to benefit from the change, ... the business community, and financial institutions in particular ..." Soon after Bush's State of the Union speech, the Club for Growth began running television advertisements in the districts of Republican members of Congress whom it identified as undecided on the issue.

A group backed by labor unions called "Americans United to Protect Social Security" "set its sights on killing Bush's privatization plan and silencing his warnings that Social Security was 'headed toward bankruptcy.'"

On January 16, 2005, the New York Times reported internal Social Security Administration documents directing employees to disseminate the message that "Social Security's long-term financing problems are serious and need to be addressed soon", and to "insert solvency messages in all Social Security publications".

Coming soon after the disclosure of government payments to commentator Armstrong Williams to promote the No Child Left Behind Act, the revelation prompted the objection from Dana C. Duggins, a vice president of the Social Security Council of the American Federation of Government Employees, that "Trust fund dollars should not be used to promote a political agenda."

In the weeks following his State of the Union speech, Bush devoted considerable time and energy to campaigning for privatization. He held "town meetings" at many locations around the country. Attendance at these meetings was controlled to ensure that the crowds would be supportive of Bush's plan. In Denver, for example, three people who had obtained tickets through Representative Bob Beauprez, a Republican, were nevertheless ejected from the meeting before Bush appeared, because they had arrived at the event in a car with a bumper sticker reading "No More Blood for Oil".

Opponents of Bush's plan have analogized his dire predictions about Social Security to similar statements that he made to muster support for the 2003 Invasion of Iraq.

A dispute between the AARP and a conservative group for older Americans, USA Next, cropped up around the time of the State of the Union speech. The AARP had supported Bush's plan for major changes in Medicare in 2003, but it opposed his Social Security privatization initiative. In January 2005, before the State of the Union Address, the AARP ran advertisements attacking the idea. In response, USA Next launched a campaign against AARP. Charlie Jarvis of USA Next stated: "They [AARP] are the boulder in the middle of the highway to personal savings accounts. We will be the dynamite that removes them."

The tone of the debate between these two interest groups is merely one example among many of the tone of many of the debates, discussions, columns, advertisements, articles, letters, and white papers that Bush's proposal, to touch the "third rail", has sparked among politicians, pundits, thinktankers, and taxpayers.

Immediately after Bush's State of the Union speech, a national poll brought some good news for each side of the controversy. Only 17% of the respondents thought the Social Security system was "in a state of crisis", but 55% thought it had "major problems". The general idea of allowing private investments was favored by 40% and opposed by 55%. Specific proposals that received more support than opposition (in each case by about a two-to-one ratio) were "Limiting benefits for wealthy retirees" and "Requiring higher income workers to pay Social Security taxes on ALL of their wages". The poll was conducted by USA Today, CNN, and the Gallup Organization.

Bush's April press conference, in which for the first time he expressly endorsed benefit reductions, sparked disagreement about where the burden would fall. Bush referred to "people who are better off". Many media summaries accepted the characterization that "wealthy" retirees would be affected, and that benefits for lower-income people would grow. Opponents countered that middle-class retirees would also experience cuts, and that those below the poverty line would receive only what they are entitled to under current law. Democrats also expressed concern that a Social Security system that primarily benefited the poor would have less widespread political support. Finally, the issue of private accounts continued to be a divisive one. Many legislators remained opposed or dubious, while Bush, in his press conference, said he felt strongly about the point.

Despite Bush's emphasis on the issue, many Republicans in Congress were not enthusiastic about his proposal, and Democrats were unanimously opposed. In late May 2005, House Majority Whip Roy Blunt listed the "priority legislation" to be acted on after Memorial Day; Social Security was not included, and Bush's proposal was considered by many to be dead. In September, some Congressional Republicans pointed to the budgetary problems caused by Hurricane Katrina as a further obstacle to acting on the Bush proposal. Congress did not enact any major changes to Social Security in 2005, or before its pre-election adjournment in 2006.

During the campaigning for the 2006 midterm election, Bush stated that reviving his proposal for privatizing Social Security would be one of his top two priorities for his last two years in office. In 2007, he continued to pursue that goal by nominating Andrew Biggs, a privatization advocate and former researcher for the Cato Institute, to be deputy commissioner of the Social Security Administration. When the Senate did not confirm Biggs, Bush made a recess appointment, enabling Biggs to hold the post without Senate confirmation until December 2008. During his last days in office, Bush said that spurring the debate on Social Security was his most effective achievement during his presidency.

Other concerns

Some allege that George W. Bush is opposed to Social Security on ideological grounds, regarding it as a form of governmental redistribution of income from the wealthy, which other groups such as libertarians strongly oppose. Some of the critics of Bush's plan argued that its real purpose was not to save the current Social Security system, but to lay the groundwork for dismantling it. They note that, in 2000, when Bush was asked about a possible transition to a fully privatized system, he replied: "It's going to take a while to transition to a system where personal savings accounts are the predominant part of the investment vehicle. ... This is a step toward a completely different world, and an important step." His comment is consonant with the Cato Institute's reference in 1983 to a "Leninist strategy" for "guerrilla warfare" against both the current Social Security system and the coalition that supports it."Critics of the system, such as Nobel Laureate economist Milton Friedman, have said that Social Security redistributes wealth from the poor to the wealthy. Workers must pay 12.4%, including a 6.2% employer contribution, on their wages below the Social Security Wage Base ($102,000 in 2008), but no tax on income in excess of this amount. Therefore, high earners pay a lower percentage of their total income, resulting in a regressive tax. The benefit paid to each worker is also calculated using the wage base on which the tax was paid. Changing the system to tax all earnings without increasing the benefit wage base would result in the system being a progressive tax.

Furthermore, wealthier individuals generally have higher life expectancies and thus may expect to receive larger benefits for a longer period than poorer taxpayers, often minorities. A single individual who dies before age 62, who is more likely to be poor, receives no retirement benefits despite years of paying Social Security tax. On the other hand, an individual who lives to age 100, who is more likely to be wealthy, is guaranteed payments that are more than he or she paid into the system.

A factor working against wealthier individuals and in favor of the poor with little other retirement income is that Social Security benefits become subject to federal income tax based on income. The portion varies with income level, 50% at $32,000 rising to 85% at $44,000 for married couples in 2008. This does not just affect those that continue to work after retirement. Unearned income withdrawn from tax deferred retirement accounts, like IRAs and 401(k)s, counts towards taxation of benefits.

Still other critics focus on the quality of life issues associated with Social Security, claiming that while the system has provided for retiree pensions, their quality of life is much lower than it would be if the system were required to pay a fair rate of return. The party leadership on both sides of the aisle have chosen not to frame the debate in this manner, presumably because of the unpleasantness involved in arguing that current retirees would have a much higher quality of life if Social Security legislation mandated returns that were merely similar to the interest rate the U.S. government pays on its borrowings.

Effects of the gift to the first generation

It has been argued that the first generation of social security participants have, in effect, received a large gift, because they received far more benefits than they paid into the system. Robert J. Shiller noted that "the initial designers of the Social Security System in 1935 had envisioned the building of a large trust fund", but "the 1939 amendments and subsequent changes prevented this from happening".As such, the gift to the first generation is necessarily borne by subsequent generations. In this pay-as-you-go system, current workers are paying the benefits of the previous generation, instead of investing for their own retirement, and therefore, attempts at privatizing Social Security could result in workers having to pay twice: once to fund the benefits of current retirees, and a second time to fund their own retirement.

Pyramid or Ponzi scheme claims

Critics have noted that the funding mechanism of an illegal Ponzi scheme, where early "investors" are paid off out of the funds collected from later investors instead of out of profits from business activity, has similarities with Social Security's pay-as-you-go funding mechanism, in particular a sustainability problem when there is a declining number of new paying entrants.William G. Shipman of the Cato Institute argues:

In common usage a trust fund is an estate of money and securities held in trust for its beneficiaries. The Social Security Trust Fund is quite different. It is an accounting of the difference between tax and benefit flows. When taxes exceed benefits, the federal government lends itself the excess in return for an interest-paying bond, an IOU that it issues to itself. The government then spends its new funds on unrelated projects such as bridge repairs, defense, or food stamps. The funds are not invested for the benefit of present or future retirees.

This criticism is not new. In his 1936 presidential campaign, Republican Alf Landon called the trust fund "a cruel hoax". The Republican platform that year stated, "The so-called reserve fund estimated at forty-seven billion dollars for old age insurance is no reserve at all, because the fund will contain nothing but the Government's promise to pay, while the taxes collected in the guise of premiums will be wasted by the Government in reckless and extravagant political schemes."

The Social Security Administration responds to the criticism as follows:

See also

References

Further reading

Interactive graphics

Articles

Speeches

Debate Category:United States economic policy Category:Article Feedback Pilot

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.