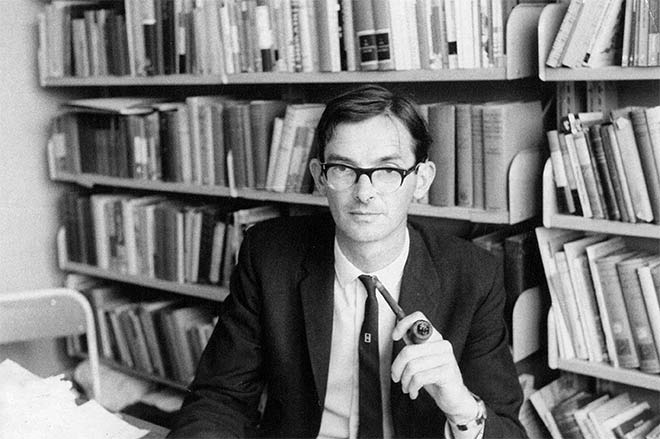

Bill Oliver, 1925–2015

It’s sad to record the passing on 16 September of William Hosking Oliver, one of the pioneers of the teaching of New Zealand history in New Zealand universities, and the founding editor of the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography (now part of Te Ara).

Bill was born in Feilding and attended school there and in Dannevirke. He was proud of his Cornish ancestors and his roots in middle New Zealand. He studied at Victoria University College in Wellington, where he came under the spell of History Professor Fred Wood. He went off to complete a doctorate at Oxford University (on British Millennialists) before returning to teach at Canterbury and Massey universities.

It was at Massey that Bill established the first course that focused on New Zealand history, and he published a pioneering history, The story of New Zealand (Faber and Faber), almost simultaneously with Keith Sinclair’s History of New Zealand (Penguin). Sinclair’s book came to be reprinted many times, and Bill’s was not, possibly because of its more discursive and essayistic style, cast in elegant prose and avoiding the Great Men and Great Events school of historiography. It still reads beautifully.

Oliver and Sinclair were longtime colleagues and friends, both poets and essayists as well as historians of New Zealand. They mingled with other writers and artists in their youth, and fruitfully sparred with each other on DNZB committees.

In the early 1980s Bill Oliver took on the role of founding editor of a new dictionary of national biography for New Zealand. He was determined as ever to make this, usually the most nationalistic of historical monuments, as representative of the actual makeup of the country as possible. This was a difficult challenge, especially in the selection of biographies for inclusion in the first volume, which covered the years in which the islands were discovered by Europeans, the British colony founded and settlement begun. The historians and other interested parties whom Bill consulted and formed into working parties had definite views and firm ideas about who was to be ‘in’ and who was not. Bill’s democratic plan was to include many Māori and many more women than were usually encountered in such compilations. This didn’t leave as much room for the pale patriarchal people and many noses were put out of joint. Bill stuck to his principles and a unique and memorable collection of lives enriched New Zealand’s historiography.

Alongside this achievement was the publication of a parallel volume of Māori-language lives of Māori people. This bicultural initiative was another pioneering achievement, assisted and continued by Bill’s successor as general editor, Claudia Orange.

One of the distinguishing features of Bill’s editorship was his guiding hand in matters of structural editing and style. Staff were treated to Bill’s handwritten comments on their editing, in terms of the balance and structure of a life as well as in identifying detailed (in Bill’s hand, always ‘detailled’ – he never could spell that word) points of fact and nuances, drawing on his immense knowledge of New Zealand history and the primary sources of information. These comments were expressed in economic and graceful prose. (Bill’s editorial principles and practices have been outlined in a previous post to this blog).

Bill was awarded a CBE for this achievement, and the project was fortunate to have his ongoing interest and attention, as he continued to provide advice and detailled [sic!] commentary for all future volumes of the DNZB after his retirement.

I suspect that all who worked alongside Bill (not ‘for’ him – he seldom pulled rank) will count it among the most satisfying, stimulating and rewarding periods in their lives.

In recent years Bill’s activities have been compromised by ill health, though his mind and interest have remained active. Few people, and certainly not Bill himself, had anticipated he would live to such a ripe old age, but those who have had the pleasure of his company will cherish the memory of the gentle and wise man who was happy to discuss all manner of contemporary subjects, and also to share the details of a long and full life. He’d had to give up most of his ‘vices’ over the years, but his memories of them were animated and cheerful. Recently he told me about his time manpowered into the broadcasting service at the end of the Second World War, and chortled over the jazz records he ‘borrowed’ from the service and took home to enliven student parties. He’d been reading to me from Rachel Barrowman’s recent biography of Maurice Gee, enlivened by erudite and amusing commentary. I’m going to miss his quiet charm and wise conversation. Nice that he’s left an enduring legacy and a cohort of friends and colleagues to celebrate knowing him.

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted