Low Unemployment with falling Capacity Utilization… Not a good sign for Fed Liftoff

Should the Fed raise the base interest rate? They really shouldn’t at this point. Will they? They probably will because they still see years of growth. I do not see years of growth ahead… Let me explain.

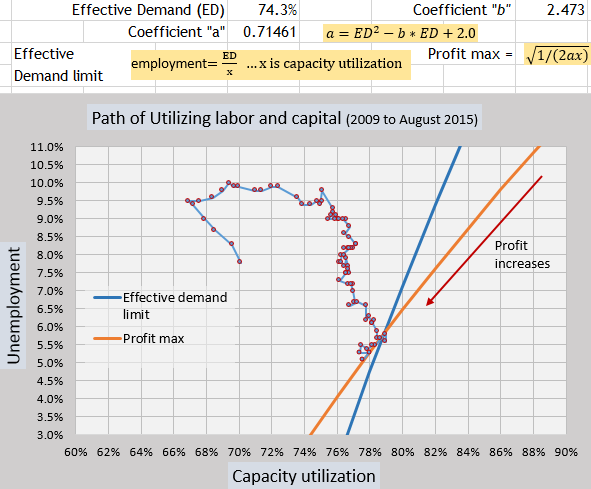

Almost one year ago I wrote that capacity utilization would start falling. (link) It has fallen since that time, even until today’s report that capacity utilization in August was 77.6%. This number was below expectations but perfectly in line with a limit line in a model that I use.

The model plots the movement of capacity utilization and unemployment. The model has two limit lines that act upon the increasing utilization of labor and capital. One for Effective Demand (basically labor share) and one for Profit Maximization (equation in graphs). The utilization of labor and capital moves toward the limits during a business cycle to increase profits. Once the movement hits the limits, profits are further increased by only moving downward along the limits, which means that capacity utilization will decrease as unemployment falls. This pattern has existed for decades before a recession. When the plot starts to pull away from the limits, a recession is beginning.

Here is the model from a year ago.

When I saw the plot reaching the limit lines last year, I wrote…

“My sense is that firms are in a race to maintain profit shares at the end of a business cycle. They felt the chill of declining profits in September. From here on out, firms will have to contract in order to maintain profit shares, as seen by the plot hitting the orange line. Now firms will have to contract capital utilization while trying to maintain the same output in order to maintain profit rates.”

So here is the model with data since September of 2014. The coefficients seen at the top are the same in both graphs for easier comparison. The coefficients though can change if labor share was to significantly change.

Yes, everyone loves the fact that unemployment is falling, but at the same time capacity utilization is falling perfectly to keep profits maximizing. Is that a good thing? Well, the business cycle stays alive and more people get hired. However, this process has its limits. Capacity utilization is now being maxed out on profits. Generally throughout the economy, it is currently only profitable to lower unemployment at some cost of capacity utilization. When capacity gets restricted too much without labor share rising, a recession becomes easier to trigger. Then we would see the plot moving up and to the left with capacity utilization falling and unemployment rising.

So the Fed decides this week whether they should raise the Fed rate or not. They are encouraged by the low unemployment number. Yet, from my perspective, the economy is very close to the end of the business cycle and too sensitive to tightening of monetary policy. The Fed could push the economy into a recession with a Fed rate rise. Basically, the Fed can no longer raise the Fed rate during this business cycle. It is too late.

According to the graphs, the natural rate of unemployment would be where the plot touches the limit lines. In this business cycle, it appears to be around 5.6%. So we have already passed the natural rate of unemployment. It is doubtful that we will see much if any inflation as conditions just do not support inflation with low interest rates promoting supply vis-a-vis weak labor share of income.

So the Fed is seeing that unemployment will drop further, and they expect some rise in inflation. However, if they are expecting a few more years of growth in this business cycle… I beg to differ.

In order to extend the life of this business cycle, the Fed should really not liftoff the interest rate.

Update:

J.Goodwin in the comments below requested a look at this model for the 1980′s. Here it is. You will see that the effective demand limit was higher at 80.2%. The “b” coefficient is the same as now. The movement of capacity utilization and unemployment headed straight for the crossing point of the two limits as they did in this business cycle. You will also see that in mid 1989, capacity utilization started to fall abruptly leading up to the recession a bit later.

You will also notice in the middle of the plot that in 1986, capacity utilization fell abruptly while unemployment stayed fairly steady. 1986 and 1987 were a global crisis of foreign debt which stressed business. But in the end the economy pushed through the problems because there was still effective demand to expand the utilization of capital and labor together.