Louis Adamic's history of the Molly Maguires: a secret society of Irish-born mine workers in the US who terrorised the exploitative mine bosses of the time.

In the US in the mid-19th century trade-unionism was tame and timorous. Most of the strikes ended disastrously for the labor organizations concerned. There were labor unions whose membership pledged itself to "avoid exciting topics." Labor leaders, so called, were for the most part men who neither labored nor led: aspiring third-rate politicians and windy orators who had little capacity for understanding the new industrial forces as they affected the worker; or reformers and lopsided idealists, full of lovely vagaries and longings, who had drawn their original inspiration and their terminology from the writings of the utopian Socialists and the Brook-Farmers. They met in labor conventions to pronounce solemnly upon the nobility of toil and recite verses about the golden sweatdrops upon the laborer's honest brow, which "shine brighter than diamonds in a coronet."

They used rhetoric to hide their confusion in the face of reality. With the exception of Horace Greeley, who, however, devoted himself mainly to the printers, the labor movement of the time produced no leader of any ability. Opportunities to enrich themselves lured competent men into commercial enterprises and into politics on the side of big money.

The worker was told by his leaders that he was "Nature's nobleman," while as a matter of fact he was the cheapest commodity on the industrial market and was lucky if his immediate circumstances permitted him to throw up his job in the mill or the mine and find himself a tract of land in the wilderness.

In sharp contrast with the ineffective regular labor organizations of that time, we have the Molly Maguires, a secret miners' society in the anthracite region of Pennsylvania in the late sixties and early seventies, whose principal method of achieving its ends was terrorism - murder.

The background of the American Molly Maguires reaches back into feudalistic Ireland of the fourth decade of the nineteenth century. There lived then an energetic dame, the widow Molly Maguire, who did not believe in the rent system that was in effect in her country and became the leading spirit of a loosely organized resistance to it.

She was a barbaric and picturesque character. She blackened her face and under her petticoat carried a pistol strapped to each of her stout thighs. Her special aversions were landlords, their agents, bailiffs, and process - servers, and her expression of hatred was limited to beating them up or murdering them. This she did with her own hands or through her "boys," who called themselves Molly Maguires, or Mollies for short. She was down on the government, which aided the tyrannical landlords in collecting the rent. She was the head of the so-called Free Soil Party, whose banner was her red petticoat. If a landlord or his agent evicted a peasant who was not meeting his payments, that landlord or agent was usually as good as dead. The Mollies, if not Mrs. Maguire herself, were sure to hear of it; eventually the man's corpse would be found in some ditch or even upon the floor of his own house.

Molly's systematic assassinations were so effectual that for a time parts of Ireland-notably Tipperary, West Meath, King's and Queen's Counties-became uninhabitable except for Mollies. Finally, the authorities, at the behest of desperate landowners, began to persecute Molly and her "boys," until, in the fifties, hordes of them, including, it appears, Molly herself, emigrated to America.

Many of them sought work in the Pennsylvania coal mines.

The Molly Maguires, as a secret order, already existed in the United States in the mid-fifties. To become a member one had to be Irish or of Irish descent, a good Roman Catholic, and also "of good moral character."

More or less officially (for the organization acquired a charter in Pennsylvania under the name of "The Ancient Order of Hibernians") their purpose was to "promote friendship, unity, and true Christian charity among the members; and, generally, to do all and singular matters and things which shall be lawful to the well-being and good management of the affairs of the association." Officially, they meant to attain these ends "by raising or supporting a stock or fund of money for maintaining the aged, sick, blind, and infirm members." Their constitution further declared that

"the Supreme Being has implanted in our natures tender sympathies and most humane feelings toward our fellow creatures in distress; and all the happiness that human nature is capable of enjoying must flow and terminate in the love of God and our fellows."

But while such was the pious basis for the order's official existence, actually the Molly Maguires became fiercer in the United States than they had been in the Old Country - and, perhaps, with good reason.

When the Mollies were at the height of their power - early in the seventies - outrage followed outrage until the coal regions of Pennsylvania became a byword for terror. Wives trembled when their husbands spoke of visiting the mining districts. People feared to stir out after dark, and never budged in broad daylight without a pistol-which, however, availed them little, for the assassins seemed invariably to get in the first shot.

A contemporary writer, in the American Law Review for January 1877, described the anthracite regions of that day as "one vast Alsatia."

… From their dark and mysterious recesses there came forth to the outside world an appalling series of tales of murder, of arson, and violent crime of every description. It seemed that no respectable man could be safe there, for it was from the respectable classes that the victims were by preference selected; nor could anyone tell from day to day whether he might not be marked for sure and sudden destruction. Only the members of one calling could feel any certainty as to their fate. These were the superintendents and "bosses" in the collieries; they could all rest assured that their days would not be long in the land. Everywhere and at all times attacked, beaten, and shot down, on the public highways and in their own homes, in solitary places and in the neighborhood of crowds, these doomed men continued to fall in frightful succession beneath the hands of assassins.

There can be no doubt, however, that the treatment accorded the workers by the responsible mine operators was such as to justify the feelings of resentment and revenge that could prompt these Irish miners to such drastic deeds.

The wages were low. Miners were paid by the cubic yard, by the car, or by the ton, and, in the driving of entries, by the lineal yard; there was much cheating in weighing and measuring on the part of the bosses. Little, if any, attention was paid by the owners, of their own accord, to the safety of the miners. Cave-ins were frequent, entombing hundreds of men every year. When and wherever possible, the employers took advantage of the men.

There were all sorts of petty difficulties at the mines. There were, for instance, "soft jobs" and "hard jobs." A miner naturally preferred a soft job. Irishmen considered themselves superior to the other foreigners, who were also beginning to come to the mines, and hence demanded the soft jobs for themselves. If refused, a Molly was naturally displeased, and his displeasure could immediately get the boss thrashed within an inch of his life, if not eventually murdered. On the other hand, if the boss should hire a Molly, there was always the possibility that the two would get into a row over the measuring of the quantity or the estimation of the quality of the miner's coal. And to disagree with a Molly was almost certain death.

For a time many bosses refused to employ Irishmen altogether, but they all died by violence. If a superintendent dared to come forward in support of his mining boss against the Molly, he, too, became a marked man and eventually was beaten up or assassinated.

But the bosses were not the Mollies' only enemies. The Mollies also had a thoroughly Irish contempt for the faint hearted, ineffectual methods of the regular labor unions.

Several labor leaders and Socialistic orators were murdered in Pennsylvania during this period-in all probability by the Mollies.

Some of the foremost Mollies were also leaders of nonsecret miners' organizations. A group of them, for example, controlled the Miners' and Laborers' Benevolent Association, and were responsible for the unfortunate "long strike" for higher wages in 1874-1875, during which, after suffering had become acute among the strikers, the Mollies kept them from returning to work by threats of murder.

In the killings were performed in a cool, deliberate, almost impersonal manner.

The Molly who wanted a boss assassinated reported his grievance in the prescribed manner to the proper local committee. If the latter approved of the wronged Molly's request, as it ordinarily did, two or more Mollies not personally or directly interested in the case were selected from a different locality, usually from another county, to do the "job," so that, being unknown, they could not be easily identified. If a Molly to whom the killing had been assigned refused to carry it out, he himself was likely to die.

The grievance committees were wont to meet in the back rooms of saloons run by fellow Mollies and, after the completion of the act, celebrate the "clean job" with the killers in good Irish fashion. Most Mollies were true sons of their spiritual mother, the widow Maguire: strong, dynamic, robust fellows, carousers, drinkers, fighters, brawlers, but good and faithful husbands and fathers. They led a "pure family life." Most of them were deeply religious. Meetings at which murders were planned often began with prayers. They went regularly to confession. Molly Maguire killings were not considered personal sins by the killers, but incidents in a "war," so they did not confess them, although the Roman Catholic Church in America had, of course, officially condemned the organization and its terroristic doings.

James Ford Rhodes, in a paper which he read in 1909, before the American Academy of Arts and Letters in Washington, ventured to explain the Molly Maguire psychology as follows:

Subject to tyranny at home, the Irishman, when he came to America, too often translated liberty into license, and so ingrained was his habit of looking upon government as an enemy [due to the seven centuries of misgovernment of Ireland by England] that, when he became the ruler of cities and stole the public funds, he was, from his point of view, only despoiling the old adversary. With this traditional hostility to government, it was easy for him to become a Molly Maguire, while the English, Scotch, and Welsh immigrant shrank from such a society with horror.

In the decade beginning with 1865, Molly Maguire killings were frequent, with few arrests, fewer trials, and never a conviction for murder in the first degree. The killers were always strangers in the locality, usually young men, quick on their legs, who had already made their escape before anybody began to pursue them. If one was caught, there always were a dozen Mollies ready to swear by the Lord God and the Holy Virgin that the accused had been with them every minute in the evening of the murder. They packed juries and selected judges.

Using the same drastic tactics, Molly Maguire leaders invaded the political field and, setting themselves up as "bosses," installed mayors and judges who were members of the order (just as nowadays "racketeers" put their men into public office in New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia).

Early in the seventies they developed considerable political power in Pennsylvania, especially in Schuylkill County, where five or six hundred Mollies ruled communities of tens of thousands.

Molly Maguire-ism was at its height in 1873 and 1874. Mining bosses and other men displeasing to the Mollies were falling dead week after week. Coal trains were wrecked. However, many killings and outrages attributed to the Mollies unquestionably were committed by other persons.

There were then several thousand Molly Maguire lodges in Pennsylvania, with a central executive body. The organization was about to gain a foothold in West Virginia when, on the initiative of a young mine-operator whose bosses were being killed with great regularity, the part of organized society in Pennsylvania not controlled by the Mollies began a determined secret action against the terrorists. Detectives of Irish descent went to work in the mines and, after joining the order, became the "biggest Mollies of Mollies," or killers of the first water, and as such were in position to spot the leaders.

In 1875, after a number of especially gruesome murders, several leaders and members of the order were arrested and tried. Pinkerton detectives - notably one James McParland, who subsequently figured in other labor cases - were practically the only witnesses against them.

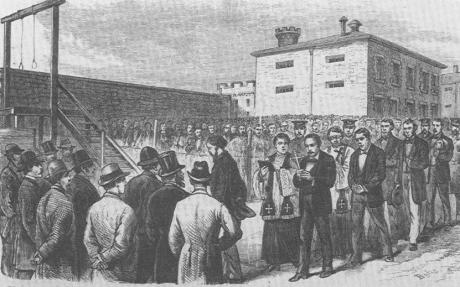

Whether any of the accused were directly guilty of the murders with which they were charged is extremely questionable, but in the course of the next few years ten Mollies were executed and fourteen imprisoned for long terms.

Thereafter the Molly Maguires as a terrorist organization rapidly disintegrated. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, however, exists to this day.

However shocking it may seem to a person who has led a sheltered life, the appearance of organized terrorism at that time and place was quite natural; indeed, it is a wonder that it was not more widespread.

Some of the explanations for the Mollies-namely, the utter ineffectiveness of the regular labor unions in the face of brutal industrial conditions, the criminal disregard for the miners' safety on the part of the employers, and the intense Irish temperament produced by centuries of misrule and injustice in the Old Country - I have already offered. Coal and more coal, was the important thing; the countless new machines in the factories and the new railroad locomotives had to have their motive power; and the men who mined the coal scarcely mattered. Immigrants hungry for work, any kind of work, were coming to the United States by the thousands every week. Hence, if a dozen miners lost their lives in a disaster, it was a matter of scant importance to the employer, and he was little inclined to do anything to prevent accidents in the future unless he happened to fear the Mollies. By killing mineowners and bosses by the dozen, by beating up hundreds of others, the Mollies unquestionably improved the working conditions not only for themselves but for all the miners in the anthracite regions of Pennsylvania, and saved many workers' lives. There is no doubt, however, that many Molly Maguire killings were motivated by petty, personal grudges.

On the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of the Molly Maguire executions by the State of Pennsylvania, Eugene V. Debs, then at the height of his career as a radical leader in America, wrote in the Appeal to Reason:

They all protested their innocence and all died game. Not one of them betrayed the slightest evidence of fear or weakening. Not one of them was a murderer at heart. All were ignorant, rough and uncouth, born of poverty and buffeted by the merciless tides of fate and chance… To resist the wrongs of which they and their fellow-workers were victims and to protect themselves against the brutality of their bosses, according to their own crude notions, was the prime object of the organization of the Molly Maguires… It is true that their methods were drastic, but it must be remembered that their lot was hard and brutalizing; that they were the neglected children of poverty, the product of a wretched environment… The men who perished upon the scaffold as felons were labor leaders, the first martyrs to the class struggle in the United States.

In the Molly Maguires we have the first beginnings of "racketeering" in America, especially labor racketeeringto use a term that has come into use since 1920. The Mollies whom the State of Pennsylvania hanged in the seventies are considered heroes today by not a few leaders and members of some of the "conservative" labor unions. The Molly Maguire organization disintegrated in the seventies, but the Molly Maguire spirit, constantly stimulated by the brutal and brutalizing working conditions in industry, went marching on through the eighties and the nineties into the current century, and-as we shall see toward the end of this book-it marches on today with a firmer step than ever before.

This text has been excerpted, and very slightly edited by libcom.org to make sense as a stand-alone text, from Louis Adamic's excellent book, Dynamite: the story of class violence in America.

Can comment on articles and discussions

Can comment on articles and discussions

Comments

I admit that I haven't read the book, but there is another dimension to the story that I learned as a boy growing up in Wilkes-Barre. Mining in NE Pennsylvania was originally started by Welsh miners who became the class of mine owners. They employed the Irish immigrants as labor and exploited them pitilessly. The Irish response were the Mollies. As a countermove, the mine owners went to the Carpathian Mts. to recruit the most skilled european miners of the day. These were Slovaks (then part of Hungary) and Poles. The reaction of the Mollies was a kind of nativism where the terrorist tactics the article describes were turned on the new immigrants.

But, there was a curious twist to the story. The new arrivals didn't like to be exploited any more than the Irish. They organized several strikes. But, these were different than those organized by the Mollies. When the Irish went on strike, they soon returned to work as their reserves ran out. By contrast, when the Slavs went out, they didn't come back. The Poconos are very similar to the Carpathians which had provided them everything they needed for a millenium. Plus, the Welsh were no match for the Hungarians when it came to brutal exploitation. In the end, the Mollies were replaced by a variety of unions that eventually merged to become the UMW.

Just came across this song, thought it belonged on this thread: