Two great American cities have now faced near-death experiences in the 21st century. While Detroit’s gradual slide into bankruptcy and the almost biblical inundation of New Orleans in 2005 look quite different on the surface, I’m more struck by the similarities. Both these tragic events were a long time coming. Only the earlier one involved a literal act of God – although the Almighty was goosed along a bit by rising carbon emissions and rising temperatures – but both could clearly have been prevented. Both tragedies were shaped by larger economic forces and historical trends that lay (or at least appeared to lie) beyond the control of individual politicians or policy makers. Then there’s the obvious but uncomfortable fact that both are cities with large black majorities, in a country where African-Americans are only about 13 percent of the population.

But Detroit and New Orleans are not just cities where lots of black people happen to live. They are uniquely important and symbolic centers of African-American culture in particular and American culture in general, whose influence spread into every luxury high-rise, every suburban street and every farmhouse in the country. Both cities have been rigidly resegregated now, but at their cultural height both were places of tremendous fusion and ferment. Jazz was born from the children and grandchildren of kidnapped Africans learning to play European instruments for the dance parties of biracial French-speaking aristocrats; Berry Gordy’s great Motown recordings borrowed the Detroit Symphony’s string section to create what he called “the Sound of Young America,” driving white teenagers to shake a tail feather at sock hops across the land.

The cultural legacy of New Orleans and Detroit is not limited by race or geography. Even before it went around the world, jazz traveled up the Mississippi on riverboats, which is how Louis Armstrong (according to legend) met an Iowa kid named Bix Beiderbecke, who would become the era’s second greatest trumpet player. Detroit produced not just the black-owned Motown empire, but also shaped the future of rock with a thriving underground scene that included the MC5, Iggy and the Stooges and the recently rediscovered proto-punk band Death (profiled in a recent documentary), a trio of African-American preacher’s kids who preferred Alice Cooper to Aretha Franklin. Detroit’s most famous rapper, by far, is a white kid from the suburbs.

Is it pure coincidence that these two landmark cities, known around the world as fountainheads of the most vibrant and creative aspects of American culture, have become our two direst examples of urban failure and collapse? If so, it’s an awfully strange one. I’m tempted to propose a conspiracy theory: As centers of African-American cultural and political power and engines of a worldwide multiracial pop culture that was egalitarian, hedonistic and anti-authoritarian, these cities posed a psychic threat to the most reactionary and racist strains in American life. I mean the strain represented by Tom Buchanan in “The Great Gatsby” (imagine what he’d have to say about New Orleans jazz) or by the slightly more coded racism of Sean Hannity today. As payback for the worldwide revolution symbolized by hot jazz, Smokey Robinson dancin’ to keep from cryin’ and Eminem trading verses with Rihanna, New Orleans and Detroit had to be punished. Specifically, they had to be isolated, impoverished and almost literally destroyed, so they could be held up as examples of what happens when black people are allowed to govern themselves.

Hang on, you can stop composing that all-caps comment – I don’t actually believe that what happened to Detroit and New Orleans resulted from anyone’s conscious plan. Real history is much more complicated than that. I do, however, think that narrative has some validity on a psychological level, and that some right-wingers in America are so delusional, so short-sighted and, frankly, so unpatriotic and culturally backward that they were delighted to see those cities fail and did everything possible to help them along. (I’m not exempting the Democratic political class of those cities from responsibility. Speaking broadly, those in city government there inherited an unsustainable situation in a downward-trending economy, pursued their own short-term objectives and only made things worse.)

In the wake of both Hurricane Katrina and the Detroit bankruptcy, many mainstream commentators have tried, with varying degrees of subtlety, to frame these events as “black stories,” and specifically as stories of black dysfunction and black political failure. I’m willing to bet that many white Americans still believe those hysterical early post-Katrina stories about New Orleans residents shooting at aid helicopters (all were later retracted or exposed as false), or believe there was widespread rape and murder among the 20,000 refugees in the Louisiana Superdome. (There were no homicides and only one reported sexual assault, an attempted rape.) While the Detroit situation is normally described as a failure of tax-and-spend, pro-union liberal policies, the racial coding you’ll find on Fox News and elsewhere is crystal clear – and the reader comments on any Detroit-related article, on Salon as elsewhere, will curl your hair with overt racial hatred.

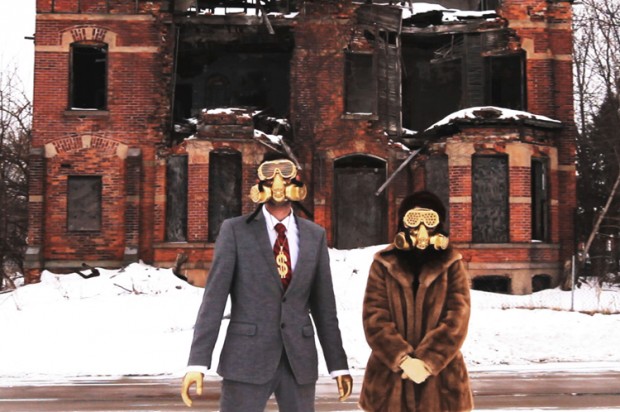

There’s definitely more going on with these two cities than old-school racial politics. Alien scientists observing these case histories from outer space might not assume, at first, that skin color had anything to do with it. New Orleans was hit by one of the biggest storms in history, and the government response was monumentally incompetent at all levels. Detroit’s bankruptcy comes toward the end of a long, dreary history: The deindustrialization of the American economy hit our most famous industrial city especially hard; the Big Three automakers blundered and mismanaged themselves into permanent mediocrity; investment capital flowed away from the Rust Belt and into low-tax, non-union jurisdictions in the Sun Belt and around the world; racial discord and rising crime drove the white middle class into the suburbs; financial inequality and the geographical separation between rich and poor became more extreme. As evidenced so memorably in Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady’s mesmerizing film “Detropia” — and if you didn’t catch it on first release, now is definitely the time — Detroit is a remarkably quiet and empty city today, one that has lost two-thirds of its 1950 population of nearly 2 million, and contains an estimated 40 square miles worth of abandoned buildings and unused land, an area larger than Manhattan.

If those E.T. scholars wrote academic papers describing the Detroit tragedy as an “overdetermined” event with many causes and many possible interpretations, they’d be right. (I realize I’ve made my aliens into Marxists; you go with what you know.) But for those of us down here on the planet’s surface, it is inescapably a tale told in black and white. Detroit is the poorest and blackest large city in the country, ringed by some of the whitest and richest suburbs. We’re now in the second term of our first African-American president, and the overt racial violence that polarized Detroit and the rest of the nation in the 1960s and ‘70s feels, most of the time, like a distant memory. New Orleans and Detroit are exceptional cities in a different sense; most American cities have become polyglot, immigrant-rich communities in which no one ethnic group is a majority, which will likely be true of the United States as a whole by the middle of this century.

But the long, hot summer of 2013 – the summer of Paula Deen’s Aunt Jemima costumes and the upside-down O.J. verdict of the George Zimmerman case and the barely concealed conservative jubilation at Detroit’s demise – has reminded us that America’s ugly old-school racial narratives die hard, if they die at all. I don’t have a policy prescription for Detroit or a fixed opinion about urban-suburban consolidation or a federal bailout or some other method of patching the city’s fiscal cracks. I do know that the people who live there, most of them black and poor, have already been victimized by several generations of high crime and failing services and the flight of capital, and are about to get beat up some more.

Instead of trying to score short-term rhetorical points or assign blame for this mess, which are the only things people on either side of the political or pundit class ever want to do, I’d like to step back and ask a different kind of question: What in the name of Christ do we imagine that people around the world think about this disaster, when they look at us? When they see one of America’s most legendary cities, a capital of the Industrial Age and of 20th-century pop culture, reduced to poverty and decrepitude and dysfunction, compelled (in all likelihood) to strip away still more of its already minimal social services and break its promises to municipal retirees? Or when they see country-club denizens of the leafy suburbs a few miles away, most of them people who grew up in Detroit and made their fortunes there, angrily protest that they have no common interest with the inhabitants of the city and no responsibility for their plight?

Does that make us look like a wise and tolerant people, a people with any understanding or reverence for our real culture and history, as opposed to the mythological version? Does it make us look confident, or intelligent, or powerful? I don’t think so. I think the collapse of Detroit makes us look the way we looked after the national humiliation of Katrina: like a bitter, miserly and dying empire where the deluded rich cling to their McMansions and mock the suffering of the poor while everyone else fights over the scraps, and where the slow-acting poison of racism continues to work its bad magic.