Branches of Mathematics

Pure mathematics

Applied mathematics

- Dynamical systems and differential equations

- Mathematical physics

- Computing

- Information theory and signal processing

- Probability and statistics

- Game theory

- Operations research

Related Topics

- Electromagnetic Spectrum

- Linear Equations

- Applied Physics

- Nano Technology

- Engineering Sciences

- Mathematical Medicine

- Fluid dynamics

- Computational Mathematics

- Gamma Ray Optics

- Onfrared Optics

- Relative Velocity

- Iciam

- Intelligent Imaging Neuroscience

- Biomedical Engineering

- Neuroscience Research

- Quantum Cosmology

- Brain Research

- Loading...

-

Introduction to Political Science

Introduction to Political Science -

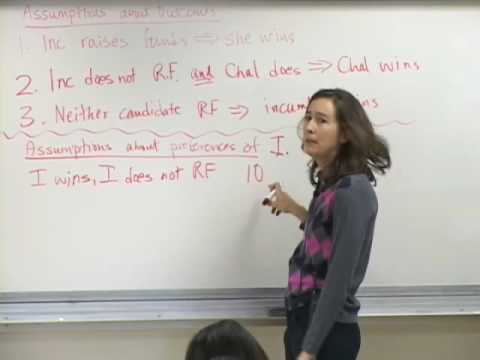

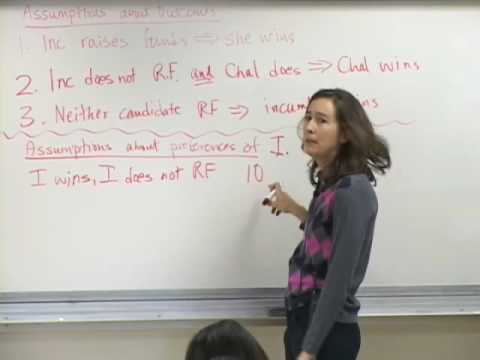

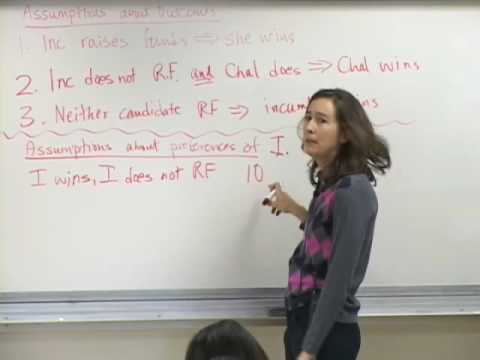

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 1, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 1, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 1, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 8th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategic... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 2, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 2, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 2, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 8th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategic... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 4, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 4, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 4, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 15th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 6, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 6, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 6, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 24th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi... -

So You Want to Get a Ph.D. in Political Science

So You Want to Get a Ph.D. in Political ScienceSo You Want to Get a Ph.D. in Political Science

An enthusiastic student gets a lesson in pursuing a Ph.D. that he may never forget. -

Advice from a Political Science (BA) student from drkit.org

Advice from a Political Science (BA) student from drkit.orgAdvice from a Political Science (BA) student from drkit.org

All Political Science Videos - http://www.drkit.org/politicalscience A student enrolled in a Political Science (BA) program provides advice for students cons... -

Civil Services Exam. : Political Science (Optional Subject)

Civil Services Exam. : Political Science (Optional Subject)Civil Services Exam. : Political Science (Optional Subject)

This lecture talks about how to prepare civil services exam. with political Science as an optional subject. -

Where can a degree in Political Science take you?

Where can a degree in Political Science take you?Where can a degree in Political Science take you?

An understanding of government and society can make you a better professional in many other fields than just law and politics. The Department of Government a... -

An Introduction to Political Science Through Classic Political Works.wmv

An Introduction to Political Science Through Classic Political Works.wmvAn Introduction to Political Science Through Classic Political Works.wmv

This is an introduction to Political Science through the works of political philosophers like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Marx, Cicero. -

So You Want To Major In Political Science...

So You Want To Major In Political Science...So You Want To Major In Political Science...

100 Reasons NOT to Go to College: http://reasonstoskipcollege.blogspot.com. -

Randy Newman - Political Science

Randy Newman - Political ScienceRandy Newman - Political Science

Randy Newman & Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, cond. Roelof van Driesten. Rotterdam, Netherlands, 1979. -

Pseudo Political Science เกมส์การเมืองล้างสมองคนไทยให้ฆ่ากัน

Pseudo Political Science เกมส์การเมืองล้างสมองคนไทยให้ฆ่ากันPseudo Political Science เกมส์การเมืองล้างสมองคนไทยให้ฆ่ากัน

นายเจษฎา เด่นดวงบริพันธ์ เครือข่ายประชาชนคือคนกลาง อาจารย์ประจำคณะวิทยาศาสตร์ จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย กล่าวว่า ขอเรียกร้องให้ประชาชนทุกคนเป็นคนกลาง ไม่ต้องให้ใ... -

Political Science 179 - 2014-10-15

Political Science 179 - 2014-10-15Political Science 179 - 2014-10-15

Political Science 179, 001 - Fall 2014 Undergraduate Colloquium on Political Science - Alan David Ross All rights reserved

- Academic discipline

- Adhocracy

- Age of Enlightenment

- Alexander Hamilton

- Alfarabi

- Americanist

- Anarchism

- Ancient Greece

- Anthropology

- Archeology

- Area studies

- Aristophanes

- Aristotelianism

- Aristotle

- Arthashastra

- Augustine of Hippo

- Averroes

- Avicenna

- Behavioralism

- Benjamin Franklin

- Bernard Berelson

- Biology

- Bowdoin College

- Brahmana

- Brandeis University

- Buddhism

- Bureaucracy

- Capitalism

- Case studies

- Category Politics

- Chanakya

- Christianity

- Cicero

- City of God (book)

- City-state

- Cognitive bias

- Colby College

- Collective action

- Communism

- Comparative politics

- Confucianism

- Constituency

- Cornell College

- Cornell University

- Corporation

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Cultural studies

- Dartmouth College

- Decision making

- Deductive reasoning

- Democracy

- Demography

- Development studies

- Dictatorship

- Directorial system

- Economic stability

- Economics

- Election

- Elections

- Electoral branch

- Empirical

- Empiricism

- Euripides

- Experiment

- Federacy

- Federalism

- Ferdowsi

- Feudalism

- Foreign policy

- Form of government

- Game theory

- Gender studies

- Geography

- Google Books

- Governance

- Governments

- Greece

- Harvard University

- Hendrix College

- Herodotus

- Hesiod

- History

- History of India

- Homer

- Human behavior

- Human geography

- Humanities

- Ideology

- Italian Renaissance

- Japan

- John Locke

- Judiciary

- Julius Caesar

- Justice

- Korea

- Lake Forest College

- Law

- Lawrence Lowell

- Laws (Plato)

- Legislature

- Liberal Arts

- Linguistics

- Livy

- Mahabharata

- Maimonides

- Manusmriti

- Marcus Aurelius

- Marist College

- Material wealth

- Meritocracy

- Methodology

- Middle Ages

- Middle Eastern

- Mixed economy

- Modernity

- Mohism

- Monarchy

- Monash University

- Moral philosophy

- Nation state

- Nation-state

- Natural law

- New York University

- Niccolò Machiavelli

- Nicomachean Ethics

- Norm (sociology)

- North America

- Occidental College

- Outline of law

- Pali Canon

- Parliamentary system

- Paul Lazarsfeld

- Peace

- Perestroika Movement

- Philip Converse

- Physics

- Pi Sigma Alpha

- Plato

- Plutarch

- Policy

- Political behavior

- Political campaign

- Political economy

- Political history

- Political lists

- Political party

- Political philosophy

- Political science

- Political system

- Political theology

- Political theory

- Politics

- Politics (Aristotle)

- Polybius

- Portal Politics

- Portal Sociology

- Positivism

- Post-structuralism

- Presidential system

- Princeton University

- Process tracing

- Psychology

- Public interest

- Public law

- Public opinion

- Public policies

- Public policy

- Public relations

- Realpolitik

- Republic

- Rig-Veda

- Robert Dahl

- Roman Empire

- Roman law

- Roman Republic

- Saint Thomas Aquinas

- Sample survey

- San José, California

- Sciences

- Scientific method

- Seneca the Younger

- Separation of powers

- Smith College

- Social contract

- Social environment

- Social research

- Social science

- Social sciences

- Sociologists

- Sociology

- Socrates

- Sophocles

- Sovereignty

- St. Martin's Press

- State (polity)

- Statistical analysis

- Stoicism

- Structuralism

- Structure and agency

- Tabula rasa

- Takshashila

- Taoism

- Template Politics

- The enlightenment

- The Republic (Plato)

- Theocracy

- Think tank

- Thomas Hobbes

- Thomas Jefferson

- Thucydides

- United States

- University of Essex

- University of Sydney

- University of Ulster

- Ursinus College

- US Congress

- Vedas

- Verstehen

- Voting

- Voting system

- Wesleyan University

- William H. Riker

- Xenophon

- Alexander Hamilton

- Aristophanes

- Aristotle

- Augustine of Hippo

- Averroes

- Avicenna

- Benjamin Franklin

- Bernard Berelson

- Chanakya

- Cicero

- Euripides

- Ferdowsi

- Herodotus

- Hesiod

- Homer

- John Locke

- Julius Caesar

- Livy

- Maimonides

- Marcus Aurelius

- Niccolò Machiavelli

- Paul Lazarsfeld

- Philip Converse

- Plato

- Plutarch

- Polybius

- Seneca the Younger

- Socrates

- Sophocles

- Thomas Hobbes

- Thomas Jefferson

- Thucydides

- Xenophon

-

Introduction to Political Science

Introduction to Political ScienceIntroduction to Political Science

What is political science? Why study political science? What are the major subdisciplines within the broad discipline of political science? What are some car... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 1, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 1, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 1, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 8th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategic... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 2, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 2, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 2, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 8th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategic... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 4, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 4, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 4, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 15th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 6, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 6, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 6, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 24th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi... -

So You Want to Get a Ph.D. in Political Science

So You Want to Get a Ph.D. in Political ScienceSo You Want to Get a Ph.D. in Political Science

An enthusiastic student gets a lesson in pursuing a Ph.D. that he may never forget. -

Advice from a Political Science (BA) student from drkit.org

Advice from a Political Science (BA) student from drkit.orgAdvice from a Political Science (BA) student from drkit.org

All Political Science Videos - http://www.drkit.org/politicalscience A student enrolled in a Political Science (BA) program provides advice for students cons... -

Civil Services Exam. : Political Science (Optional Subject)

Civil Services Exam. : Political Science (Optional Subject)Civil Services Exam. : Political Science (Optional Subject)

This lecture talks about how to prepare civil services exam. with political Science as an optional subject. -

Where can a degree in Political Science take you?

Where can a degree in Political Science take you?Where can a degree in Political Science take you?

An understanding of government and society can make you a better professional in many other fields than just law and politics. The Department of Government a... -

An Introduction to Political Science Through Classic Political Works.wmv

An Introduction to Political Science Through Classic Political Works.wmvAn Introduction to Political Science Through Classic Political Works.wmv

This is an introduction to Political Science through the works of political philosophers like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Marx, Cicero. -

So You Want To Major In Political Science...

So You Want To Major In Political Science...So You Want To Major In Political Science...

100 Reasons NOT to Go to College: http://reasonstoskipcollege.blogspot.com. -

Randy Newman - Political Science

Randy Newman - Political ScienceRandy Newman - Political Science

Randy Newman & Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, cond. Roelof van Driesten. Rotterdam, Netherlands, 1979. -

Pseudo Political Science เกมส์การเมืองล้างสมองคนไทยให้ฆ่ากัน

Pseudo Political Science เกมส์การเมืองล้างสมองคนไทยให้ฆ่ากันPseudo Political Science เกมส์การเมืองล้างสมองคนไทยให้ฆ่ากัน

นายเจษฎา เด่นดวงบริพันธ์ เครือข่ายประชาชนคือคนกลาง อาจารย์ประจำคณะวิทยาศาสตร์ จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย กล่าวว่า ขอเรียกร้องให้ประชาชนทุกคนเป็นคนกลาง ไม่ต้องให้ใ... -

Political Science 179 - 2014-10-15

Political Science 179 - 2014-10-15Political Science 179 - 2014-10-15

Political Science 179, 001 - Fall 2014 Undergraduate Colloquium on Political Science - Alan David Ross All rights reserved -

Dr Ali Muhammad Vs Polight Religion, Political Science & Economics

Dr Ali Muhammad Vs Polight Religion, Political Science & EconomicsDr Ali Muhammad Vs Polight Religion, Political Science & Economics

http://www.houseofkonsciousness.com. -

Political Science 179 - Election 2008 - Lecture 1

Political Science 179 - Election 2008 - Lecture 1Political Science 179 - Election 2008 - Lecture 1

Political issues facing the state of California, the United States, or the international community. Instructor: Alan Ross Guest Lecturer: Joe Tuman - Profess... -

Which Degree 4 me - B.A. Political Science

Which Degree 4 me - B.A. Political ScienceWhich Degree 4 me - B.A. Political Science

On September 11, 2011 I visited Harris in Washington DC to speak about his experience obtaining a B.A. in Political Science. After having graduated from UC B... -

1. Introduction: What is Political Philosophy?

1. Introduction: What is Political Philosophy?1. Introduction: What is Political Philosophy?

Introduction to Political Philosophy (PLSC 114) Professor Smith discusses the nature and scope of "political philosophy." The oldest of the social sciences, ... -

WHAT'S IN A MAJOR: Political Science

WHAT'S IN A MAJOR: Political ScienceWHAT'S IN A MAJOR: Political Science

Hear from student, Sheelah, about her experience in the Political Science program. -

Major in Political Science

Major in Political ScienceMajor in Political Science

-

UCLA Political Science Commencement June 15, 2014 Edited

UCLA Political Science Commencement June 15, 2014 EditedUCLA Political Science Commencement June 15, 2014 Edited

UCLA Political Science Commencement Ceremony June 15, 2014 Pauley Pavilion Keynote Speaker: William R. Johnson Edited, no opening processional. -

Randy Newman - Political Science [lyrics]

Randy Newman - Political Science [lyrics]Randy Newman - Political Science [lyrics]

No one likes us-I don't know why We may not be perfect, but heaven knows we try But all around, even our old friends put us down Let's drop the big one and s... -

Political Science as an Optional by Dr Nidhi

Political Science as an Optional by Dr NidhiPolitical Science as an Optional by Dr Nidhi

How to Prepare Political Science as an Optional for ias By Nidhi "Online IAS Coaching Institute" Contact Us: website: www.indiancivils.com Phone No: 90000188...

- Duration: 6:09

- Updated: 06 Sep 2014

- published: 18 Dec 2013

- views: 17778

- author: Professor Tamir Sukkary

- Duration: 72:38

- Updated: 04 Sep 2014

- published: 20 Jul 2009

- views: 91419

- author: UCLACourses

- Duration: 72:09

- Updated: 04 Sep 2014

- published: 21 Jul 2009

- views: 31168

- author: UCLACourses

- Duration: 71:18

- Updated: 15 Aug 2014

- published: 22 Jul 2009

- views: 9224

- author: UCLACourses

- Duration: 68:46

- Updated: 25 Jun 2014

- published: 23 Jul 2009

- views: 4820

- author: UCLACourses

- Duration: 3:33

- Updated: 05 Sep 2014

- published: 27 Oct 2010

- views: 272185

- author: riddlerigmarole

- Duration: 4:32

- Updated: 02 Sep 2014

- published: 04 May 2013

- views: 6172

- author: DrKitVideos

- Duration: 64:10

- Updated: 04 Sep 2014

- published: 11 Jul 2012

- views: 9515

- author: Cec Ugc

- Duration: 2:45

- Updated: 13 Aug 2014

- published: 15 Oct 2013

- views: 3911

- author: UAB Digital Media

- Duration: 11:41

- Updated: 03 Sep 2014

- published: 17 Oct 2012

- views: 7944

- author: Tafuto

- Duration: 4:10

- Updated: 05 Sep 2014

- published: 31 Jan 2012

- views: 16917

- author: HyrbidHermit

- Duration: 2:05

- Updated: 02 Sep 2014

- published: 04 Nov 2008

- views: 135554

- author: scofak

- Duration: 17:45

- Updated: 01 Sep 2014

- published: 19 May 2014

- views: 14600

- author: jessadad

- Duration: 48:12

- Updated: 16 Oct 2014

- published: 16 Oct 2014

- views: 59

- Duration: 67:59

- Updated: 03 Sep 2014

- Duration: 35:15

- Updated: 05 Sep 2014

- published: 28 May 2008

- views: 42344

- author: UCBerkeley

- Duration: 3:25

- Updated: 07 Aug 2014

- published: 01 Mar 2012

- views: 6945

- author: whichdegree4me

- Duration: 37:06

- Updated: 02 Sep 2014

- published: 21 Sep 2008

- views: 211316

- author: YaleCourses

- Duration: 9:22

- Updated: 16 Jun 2014

- published: 24 Jan 2014

- views: 271

- author: Program for Undeclared Students - Northeastern University

- Duration: 3:06

- Updated: 29 Aug 2014

http://wn.com/Major_in_Political_Science

- Duration: 83:08

- Updated: 20 Jun 2014

- published: 17 Jun 2014

- views: 487

- author: UCLA Political Science

![Randy Newman - Political Science [lyrics] Randy Newman - Political Science [lyrics]](http://web.archive.org./web/20141111191001im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/4QbUSjnhv6M/0.jpg)

- Duration: 2:12

- Updated: 18 Aug 2014

- published: 14 Jan 2012

- views: 8432

- author: 8emelios

- Duration: 66:03

- Updated: 25 Aug 2014

- published: 22 Apr 2014

- views: 153

- author: INDIANCIVILS

-

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 3, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 3, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 3, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 15th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 7, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 7, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 7, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 29th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 9, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 9, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 9, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy February 5th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi... -

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 12, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 12, UCLAPolitical Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 12, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy February 19th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strateg... -

Political Science

Political SciencePolitical Science

This Lecture talks about Political Science. -

Jathika Pasala AL) Political Science 2013 Lesson (1)

Jathika Pasala AL) Political Science 2013 Lesson (1)Jathika Pasala AL) Political Science 2013 Lesson (1)

-

Sam Houston State University Political Science Class

Sam Houston State University Political Science ClassSam Houston State University Political Science Class

Congressman Brady speaks to a political science class at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas on October 27. -

Political Science 1 Parties and Interest Groups Interest Groups

Political Science 1 Parties and Interest Groups Interest GroupsPolitical Science 1 Parties and Interest Groups Interest Groups

-

Muammar Gaddafi's address to the London School of Economics and Political Science, December 2010

Muammar Gaddafi's address to the London School of Economics and Political Science, December 2010Muammar Gaddafi's address to the London School of Economics and Political Science, December 2010

Muammar Gaddafi address to the 'London School of Economics and Political Science' (LSE), December 2010 December 2010 - only months before the war on Libya - ... -

Public Opinion, a Seminal Work in Political Science, by Walter Lippmann, Audiobook

Public Opinion, a Seminal Work in Political Science, by Walter Lippmann, AudiobookPublic Opinion, a Seminal Work in Political Science, by Walter Lippmann, Audiobook

This book is a critical assessment of functional democratic government, especially the irrational, and often self-serving, social perceptions that influence ... -

POL101 Political Science lecture: The Rise of Great Powers (part 1)

POL101 Political Science lecture: The Rise of Great Powers (part 1)POL101 Political Science lecture: The Rise of Great Powers (part 1)

-

Political Science 179 - 2014-01-22: No image

Political Science 179 - 2014-01-22: No imagePolitical Science 179 - 2014-01-22: No image

Political Science 179, 001 - Spring 2014 Creative Commons 3.0: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs. -

[Political Science] The Theory of Social Revolutions, Audiobook, by Brooks Adams

[Political Science] The Theory of Social Revolutions, Audiobook, by Brooks Adams[Political Science] The Theory of Social Revolutions, Audiobook, by Brooks Adams

[Political Science] The Theory of Social Revolutions, Audiobook, by Brooks Adams.

- Duration: 70:57

- Updated: 01 Aug 2014

- published: 21 Jul 2009

- views: 12770

- author: UCLACourses

- Duration: 73:23

- Updated: 25 Jun 2014

- published: 23 Jul 2009

- views: 4400

- author: UCLACourses

- Duration: 69:49

- Updated: 16 Feb 2014

- published: 24 Jul 2009

- views: 2635

- author: UCLACourses

- Duration: 71:24

- Updated: 18 Mar 2014

- published: 27 Jul 2009

- views: 2789

- author: UCLACourses

- Duration: 50:21

- Updated: 14 May 2014

- Duration: 53:10

- Updated: 28 Aug 2013

http://wn.com/Jathika_Pasala_AL)_Political_Science_2013_Lesson_(1)

- Duration: 44:50

- Updated: 18 Mar 2014

- published: 03 Nov 2010

- views: 1075

- author: Rep Kevin Brady

- Duration: 36:13

- Updated: 20 Apr 2014

http://wn.com/Political_Science_1_Parties_and_Interest_Groups_Interest_Groups

- Duration: 53:36

- Updated: 28 Aug 2014

- published: 26 Aug 2013

- views: 5186

- author: PGSH

- Duration: 642:39

- Updated: 21 Aug 2014

- published: 09 Dec 2013

- views: 1443

- author: Free Audio Books and Recordings

- Duration: 28:43

- Updated: 02 Aug 2014

http://wn.com/POL101_Political_Science_lecture_The_Rise_of_Great_Powers_(part_1)

- Duration: 32:21

- Updated: 07 Jun 2014

- published: 23 Jan 2014

- views: 2276

- author: UCBerkeley

![[Political Science] The Theory of Social Revolutions, Audiobook, by Brooks Adams [Political Science] The Theory of Social Revolutions, Audiobook, by Brooks Adams](http://web.archive.org./web/20141111191001im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/H32iFb8RFpo/0.jpg)

- Duration: 301:11

- Updated: 21 Aug 2014

- published: 04 Jun 2014

- views: 366

- author: Free Audio Books and Recordings

-

Worldmeets.US Broadcast News: Meet Dr. Regula Stämpfli

Worldmeets.US Broadcast News: Meet Dr. Regula StämpfliWorldmeets.US Broadcast News: Meet Dr. Regula Stämpfli

A discussion with Dr. Regula Stämpfli: Dr. Stämpfli holds a doctorate in political science and studied history and philosophy at the University of Bern. She is the author of many textbooks and articles dealing with issues such as democratic theory, European political decision making, women's history, design, political communications and political philosophy. She is also a well known political commentator on current affairs in Switzerland. -

LGBTeens: Q&A; + my birth name

LGBTeens: Q&A; + my birth nameLGBTeens: Q&A; + my birth name

Published on Sep 21, 2012 *LGBTeens Channel has shut down and changed over so I am putting all my videos up here! :)* *NOTE: I don't have a girlfriend anymore and I'm not a political science major anymore. Sorry my hair is so messy.* Hey Everyone! It's question week!! Thanks for all the great questions. I'm sorry I couldn't answer all of them. I'll answer some more within the next couple of months so keep the questions coming. If you have a question you are dying to get the answer to feel free to message me via tumblr: www.ryancassata.tumblr.com http://www.ryancassata.com http://www.facebook.com/ryancassata http://www.ryancassata.tumb -

रासायनिक नाम एवं सूत्र ( By Anita Sharma)

रासायनिक नाम एवं सूत्र ( By Anita Sharma)रासायनिक नाम एवं सूत्र ( By Anita Sharma)

My all audios in mp3. These are:- 1:- IAS Pre.G.K. study materials in Hindi Like:- G.K., Current Affairs, History , Geography, Economics, Constitution & Political Science, 2:- Fore States Like:- Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh , Chhattisgad & Uttar Pradesh G.K. in Hindi. 3:- Class 10th Science questions with their Answers in Hindi 4:- Railway entrance Exam + G.K. 5:- Bank & Computer Which are related to all entrance examination.If you are interested in purchase the CD/DVD of my audios in MP3, you can directly contact me on my e-mail ID. voiceforblind@gmail.com -

How do I find journal articles in political science and public affairs?

How do I find journal articles in political science and public affairs?How do I find journal articles in political science and public affairs?

http://adf.ly/70849/mcnwithfullapprove If you're studying public policy and international studies, there's one resource you should know about: it's called PAIS, Public Affairs Information Service. -

20141030 080721

20141030 08072120141030 080721

ULM Political Science Senate Campaign Simulation: Oct. 30 debate -

Episode 816 | Money in Elections

Episode 816 | Money in ElectionsEpisode 816 | Money in Elections

NMiF Producer Floyd Vasquez talks campaign ad spending and media coverage with New Mexico journalists, a political science professor and a long-time state legislator. -

Health Care Regionalization in Alberta: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Health Care Regionalization in Alberta: The Good, the Bad and the UglyHealth Care Regionalization in Alberta: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Dr. John Church - Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Alberta Host: University of Regina Date: October 17, 2014 -

The impact of social media and Web ads on political campaigns

The impact of social media and Web ads on political campaignsThe impact of social media and Web ads on political campaigns

Political science professors Dave Andersen and Chris Budzisz explain how campaigns are using more and more social media and Web ads to reach supporters and potential voters, in addition to the traditional broadcast television commercials. They say sophisticated campaigns are harnessing the power of new media. -

What Can I do with a Major in Political Science?

What Can I do with a Major in Political Science?What Can I do with a Major in Political Science?

SWC students packed the Career Center to listen in on a forum describing what can be done with a major in Political Science. Four distinguished Southwestern College alumni and professionals shared their career journeys and workplace assignments. The panelists gave the current “ins and outs” of their profession and discussed their experiences. The panelists for this event included: SWC Alumna, Nora Vargas, Vice President of Community & Government Relations for Planned Parenthood & SWC Board of Trustee SWC Alumnus, Robert Montano, Attorney specializing in Criminal Defense, DUI and Estate Planning SWC Alumna, Yolanda Gabriela Apalategui Lugo -

History and Political Science at Bridgewater College

History and Political Science at Bridgewater CollegeHistory and Political Science at Bridgewater College

http://www.bridgewater.edu Do you want to change the future? Become a leader in policy and law? Understand the history that has shaped our world? Check out our programs in global studies, history, political science, pre-law and public policy. With four majors, three minors and four concentrations, you have numerous options to customize your degree. The history and political science department prepares you for a life of active citizenship and intellectual engagement. In your classes you’ll engage in discussion, reflection, simulations, problem-based learning and collaborative research with faculty and your fellow students. Outside the class -

Public Opinion in the Arab World: What do the latest surveys tell us?

Public Opinion in the Arab World: What do the latest surveys tell us?Public Opinion in the Arab World: What do the latest surveys tell us?

Please join the U.S. Institute for Peace (USIP), the Arab Barometer, the Arab Reform Initiative, the Project on Middle East Democracy, and the Project on Middle East Political Science in a discussion and analysis of latest polling data from across the Middle East. learn more: http://www.usip.org/events/public-opinion-in-the-arab-world-what-do-the-latest-surveys-tell-us -

LSE Executive Summer School – Client Testimonials

LSE Executive Summer School – Client TestimonialsLSE Executive Summer School – Client Testimonials

In this short film, members of the 2014 Executive Summer School cohort share their views on this executive education programme. For more information please visit www.lse.ac.uk/ess. -

Diane Abbott on London: A Tale of Two Cities

Diane Abbott on London: A Tale of Two CitiesDiane Abbott on London: A Tale of Two Cities

Speaker: Diane Abbott MP Recorded on 22 October 2014 in CLM4.02, Clement House. The lecture will focus on the challenges facing London as a city and policy ideas to address these, chiefly the growing nature of inequality in London, the city’s growing population, the escalating housing crisis, the impact of welfare reform, and the effects of the health and social care act on public health. Additionally, the talk will seek to address the issue of powers available to City Hall in the light of the devolution question. Diane Abbott is a British Labour Party politician who has been the Member of Parliament (MP) for Hackney North and Stoke Newin -

Rituals and Ritualism in the International Human Rights System

Rituals and Ritualism in the International Human Rights SystemRituals and Ritualism in the International Human Rights System

Speakers: Professor Hilary Charlesworth Recorded on 21 October 2014 in Wolfson Theatre, New Academic Building. This lecture will consider rituals in the international human rights system and their connection to ritualism. Hilary Charlesworth is Director of the Centre for International Governance and Justice at Australian National University and Shimizu Visiting Professor at LSE Law. -

Try 1 Political Science

Try 1 Political ScienceTry 1 Political Science

-

Weeks vs. United States -- Political Science

Weeks vs. United States -- Political ScienceWeeks vs. United States -- Political Science

-

Plessy vs. Ferguson -- Political Science

Plessy vs. Ferguson -- Political SciencePlessy vs. Ferguson -- Political Science

Sarah Wright's Case Project -

Rant video political science

Rant video political scienceRant video political science

Had to slow Kobe's voice down at a certain part if you didn't notice, simply because he talks way to fast. -

อ.สมพร มุสิกะ : หยุดขบวนการล้มเจ้าด้วยการสร้างประชาธิปไตย

อ.สมพร มุสิกะ : หยุดขบวนการล้มเจ้าด้วยการสร้างประชาธิปไตยอ.สมพร มุสิกะ : หยุดขบวนการล้มเจ้าด้วยการสร้างประชาธิปไตย

ปัญหาประชาธิปไตยนั้น เกี่ยวเนื่องด้วยหลักวิชาโดยสังกัดอยู่ใน วิชาการเมือง หรือ รัฐศาสตร์ (Political Science) ซึ่งมีหลักการและกฎเกณฑ์ที่จะต้องมีความเข้าใจและยึดถืออย่างเคร่งครัดมากมาย ซึ่งเราจะคิด จะพูด จะทำเอาตามชอบใจมิได้เลย การจะสร้างประชาธิปไตยให้สำเร็จได้นั้น นอกจากจะต้องมีความเข้าใจใน ลัทธิประชาธิปไตย (Democracy) เป็นพื้นฐานแล้ว ยังจะต้องประกอบด้วยความเข้าใจปัญหาและอุปสรรคต่างๆ ที่เป็น เงื่อนไขสำคัญอีกหลายประการ กล่าวโดยสรุปก็คือ ประชาชนต้องการทราบว่า การสร้างประชาธิปไตยที่ถูกต้องทำอย่างไร หรือต้องมีความเข้าใจเป็น อย่างไรบ้าง ซึ่งจะเป็นแนวทางที่ถูกต้องและนำไปสู่การแก้ปัญหาของชาติได้ ปัญหานี้จึงเป็นที่มาของ การจัดทำเอกสารและการทำคลิปนี้ -

Police Foundations Political Science Rant: Welfare

Police Foundations Political Science Rant: WelfarePolice Foundations Political Science Rant: Welfare

-

Egypt Targets Universities as Last Haven for Political Expression

Egypt Targets Universities as Last Haven for Political ExpressionEgypt Targets Universities as Last Haven for Political Expression

Hundreds of police surround its walls, patrolling in armored vehicles with sirens blaring, while muscle-bound security guards man metal detectors, searching all who enter. But this is not a military barracks or police station. It is Cairo University, where the government has tightened security as it seeks to avert another year of unrest on university campuses, among the last bastions of protest and dissent in Egypt. The government has cracked down on critics since July 2013, when then-army chief Abdel Fattah al-Sissi overthrew Mohamed Morsi, Egypt's first freely elected president and a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, after mass protests a -

The Doctrine of Creation in Lutheran Apologetics

The Doctrine of Creation in Lutheran ApologeticsThe Doctrine of Creation in Lutheran Apologetics

Allen Quist is a retired professor of political science at Bethany Lutheran College in Mankato, Minnesota. He holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree from Gustavus Adolphus College (St. Peter, MN), a Master of Arts degree from Minnesota State University, Mankato, and a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary (Mankato, MN). Quist's essay is entitled "The Doctrine of Creation in Lutheran Apologetics" The 47th annual Bjarne Wollan Teigen Reformation Lectures begin Thursday at 10:30am. The Reformation Lectures are an annual Free Conference style lecture series held by Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary and Bethany Luth -

Malzberg | Dr. Jesse Richman to discuss the results of his research study

Malzberg | Dr. Jesse Richman to discuss the results of his research studyMalzberg | Dr. Jesse Richman to discuss the results of his research study

Associate Professor of Political Science and Geography and Faculty Director of the Social Science Research Center at Old Dominion University and lead author of the study, "Do non-citizens vote in U.S. elections?" joins Steve to discuss the results of his research study

- Duration: 0:00

- Updated: 02 Nov 2014

- published: 02 Nov 2014

- views: 0

- Duration: 4:49

- Updated: 01 Nov 2014

- published: 01 Nov 2014

- views: 179

- Duration: 8:37

- Updated: 01 Nov 2014

- published: 01 Nov 2014

- views: 10

- Duration: 3:30

- Updated: 01 Nov 2014

- published: 01 Nov 2014

- views: 0

- Duration: 55:50

- Updated: 01 Nov 2014

- published: 01 Nov 2014

- views: 5

- Duration: 12:54

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 15

- Duration: 56:07

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 1

- Duration: 2:19

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 19

- Duration: 30:46

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 1

- Duration: 3:11

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 5

- Duration: 0:00

- Updated: 29 Oct 2014

- published: 29 Oct 2014

- views: 0

- Duration: 2:09

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 511

- Duration: 37:53

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 6

- Duration: 83:27

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 848

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 3

- Duration: 2:34

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

http://wn.com/Weeks_vs._United_States_--_Political_Science

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 1

- Duration: 2:49

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 3

- Duration: 2:50

- Updated: 31 Oct 2014

- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 1

- Duration: 50:44

- Updated: 30 Oct 2014

- published: 30 Oct 2014

- views: 11

- Duration: 2:31

- Updated: 30 Oct 2014

http://wn.com/Police_Foundations_Political_Science_Rant_Welfare

- published: 30 Oct 2014

- views: 7

- Duration: 7:25

- Updated: 30 Oct 2014

- published: 30 Oct 2014

- views: 0

- Duration: 84:43

- Updated: 30 Oct 2014

- published: 30 Oct 2014

- views: 15

- Duration: 5:24

- Updated: 30 Oct 2014

- published: 30 Oct 2014

- views: 0

- Playlist

- Chat

Introduction to Political Science

What is political science? Why study political science? What are the major subdisciplines within the broad discipline of political science? What are some car...- published: 18 Dec 2013

- views: 17778

- author: Professor Tamir Sukkary

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 1, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 8th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategic...- published: 20 Jul 2009

- views: 91419

- author: UCLACourses

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 2, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 8th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategic...- published: 21 Jul 2009

- views: 31168

- author: UCLACourses

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 4, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 15th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi...- published: 22 Jul 2009

- views: 9224

- author: UCLACourses

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 6, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 24th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi...- published: 23 Jul 2009

- views: 4820

- author: UCLACourses

So You Want to Get a Ph.D. in Political Science

An enthusiastic student gets a lesson in pursuing a Ph.D. that he may never forget.- published: 27 Oct 2010

- views: 272185

- author: riddlerigmarole

Advice from a Political Science (BA) student from drkit.org

All Political Science Videos - http://www.drkit.org/politicalscience A student enrolled in a Political Science (BA) program provides advice for students cons...- published: 04 May 2013

- views: 6172

- author: DrKitVideos

Civil Services Exam. : Political Science (Optional Subject)

This lecture talks about how to prepare civil services exam. with political Science as an optional subject.- published: 11 Jul 2012

- views: 9515

- author: Cec Ugc

Where can a degree in Political Science take you?

An understanding of government and society can make you a better professional in many other fields than just law and politics. The Department of Government a...- published: 15 Oct 2013

- views: 3911

- author: UAB Digital Media

An Introduction to Political Science Through Classic Political Works.wmv

This is an introduction to Political Science through the works of political philosophers like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Marx, Cicero.- published: 17 Oct 2012

- views: 7944

- author: Tafuto

So You Want To Major In Political Science...

100 Reasons NOT to Go to College: http://reasonstoskipcollege.blogspot.com.- published: 31 Jan 2012

- views: 16917

- author: HyrbidHermit

Randy Newman - Political Science

Randy Newman & Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, cond. Roelof van Driesten. Rotterdam, Netherlands, 1979.- published: 04 Nov 2008

- views: 135554

- author: scofak

Pseudo Political Science เกมส์การเมืองล้างสมองคนไทยให้ฆ่ากัน

นายเจษฎา เด่นดวงบริพันธ์ เครือข่ายประชาชนคือคนกลาง อาจารย์ประจำคณะวิทยาศาสตร์ จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย กล่าวว่า ขอเรียกร้องให้ประชาชนทุกคนเป็นคนกลาง ไม่ต้องให้ใ...- published: 19 May 2014

- views: 14600

- author: jessadad

Political Science 179 - 2014-10-15

Political Science 179, 001 - Fall 2014 Undergraduate Colloquium on Political Science - Alan David Ross All rights reserved- published: 16 Oct 2014

- views: 59

Dr Ali Muhammad Vs Polight Religion, Political Science & Economics

http://www.houseofkonsciousness.com.- published: 14 May 2014

- views: 26510

- author: SANETERTV7

Political Science 179 - Election 2008 - Lecture 1

Political issues facing the state of California, the United States, or the international community. Instructor: Alan Ross Guest Lecturer: Joe Tuman - Profess...- published: 28 May 2008

- views: 42344

- author: UCBerkeley

Which Degree 4 me - B.A. Political Science

On September 11, 2011 I visited Harris in Washington DC to speak about his experience obtaining a B.A. in Political Science. After having graduated from UC B...- published: 01 Mar 2012

- views: 6945

- author: whichdegree4me

1. Introduction: What is Political Philosophy?

Introduction to Political Philosophy (PLSC 114) Professor Smith discusses the nature and scope of "political philosophy." The oldest of the social sciences, ...- published: 21 Sep 2008

- views: 211316

- author: YaleCourses

- Playlist

- Chat

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 3, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 15th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi...- published: 21 Jul 2009

- views: 12770

- author: UCLACourses

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 7, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy January 29th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi...- published: 23 Jul 2009

- views: 4400

- author: UCLACourses

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 9, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy February 5th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strategi...- published: 24 Jul 2009

- views: 2635

- author: UCLACourses

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy, Lec 12, UCLA

Political Science 30: Politics and Strategy February 19th, 2008 Taught by UCLA's Professor Kathleen Bawn, this courses is an introduction to study of strateg...- published: 27 Jul 2009

- views: 2789

- author: UCLACourses

Jathika Pasala AL) Political Science 2013 Lesson (1)

- published: 28 Aug 2013

- views: 562

- author: Learning Lanka

Sam Houston State University Political Science Class

Congressman Brady speaks to a political science class at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas on October 27.- published: 03 Nov 2010

- views: 1075

- author: Rep Kevin Brady

Political Science 1 Parties and Interest Groups Interest Groups

- published: 20 Apr 2014

- views: 105

- author: Tamina Alon

Muammar Gaddafi's address to the London School of Economics and Political Science, December 2010

Muammar Gaddafi address to the 'London School of Economics and Political Science' (LSE), December 2010 December 2010 - only months before the war on Libya - ...- published: 26 Aug 2013

- views: 5186

- author: PGSH

Public Opinion, a Seminal Work in Political Science, by Walter Lippmann, Audiobook

This book is a critical assessment of functional democratic government, especially the irrational, and often self-serving, social perceptions that influence ...- published: 09 Dec 2013

- views: 1443

- author: Free Audio Books and Recordings

POL101 Political Science lecture: The Rise of Great Powers (part 1)

- published: 12 Dec 2012

- views: 3322

- author: Jae Lee

Political Science 179 - 2014-01-22: No image

Political Science 179, 001 - Spring 2014 Creative Commons 3.0: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs.- published: 23 Jan 2014

- views: 2276

- author: UCBerkeley

[Political Science] The Theory of Social Revolutions, Audiobook, by Brooks Adams

[Political Science] The Theory of Social Revolutions, Audiobook, by Brooks Adams.- published: 04 Jun 2014

- views: 366

- author: Free Audio Books and Recordings

- Playlist

- Chat

Worldmeets.US Broadcast News: Meet Dr. Regula Stämpfli

A discussion with Dr. Regula Stämpfli: Dr. Stämpfli holds a doctorate in political science and studied history and philosophy at the University of Bern. She is the author of many textbooks and articles dealing with issues such as democratic theory, European political decision making, women's history, design, political communications and political philosophy. She is also a well known political commentator on current affairs in Switzerland.- published: 02 Nov 2014

- views: 0

LGBTeens: Q&A; + my birth name

Published on Sep 21, 2012 *LGBTeens Channel has shut down and changed over so I am putting all my videos up here! :)* *NOTE: I don't have a girlfriend anymore and I'm not a political science major anymore. Sorry my hair is so messy.* Hey Everyone! It's question week!! Thanks for all the great questions. I'm sorry I couldn't answer all of them. I'll answer some more within the next couple of months so keep the questions coming. If you have a question you are dying to get the answer to feel free to message me via tumblr: www.ryancassata.tumblr.com http://www.ryancassata.com http://www.facebook.com/ryancassata http://www.ryancassata.tumblr.com @ROCassataMusic - TWITTER @Ryancassata - INSTAGRAM http://www.youtube.com/xqueerkidx If you would like me to do a motivational speech at your school to educate your peers please email Sam: sam@ryancassata.com or visit www.ryancassata.com for more info! I would love to educate your school.- published: 01 Nov 2014

- views: 179

रासायनिक नाम एवं सूत्र ( By Anita Sharma)

My all audios in mp3. These are:- 1:- IAS Pre.G.K. study materials in Hindi Like:- G.K., Current Affairs, History , Geography, Economics, Constitution & Political Science, 2:- Fore States Like:- Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh , Chhattisgad & Uttar Pradesh G.K. in Hindi. 3:- Class 10th Science questions with their Answers in Hindi 4:- Railway entrance Exam + G.K. 5:- Bank & Computer Which are related to all entrance examination.If you are interested in purchase the CD/DVD of my audios in MP3, you can directly contact me on my e-mail ID. voiceforblind@gmail.com- published: 01 Nov 2014

- views: 10

How do I find journal articles in political science and public affairs?

http://adf.ly/70849/mcnwithfullapprove If you're studying public policy and international studies, there's one resource you should know about: it's called PAIS, Public Affairs Information Service.- published: 01 Nov 2014

- views: 0

Episode 816 | Money in Elections

NMiF Producer Floyd Vasquez talks campaign ad spending and media coverage with New Mexico journalists, a political science professor and a long-time state legislator.- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 15

Health Care Regionalization in Alberta: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Dr. John Church - Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Alberta Host: University of Regina Date: October 17, 2014- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 1

The impact of social media and Web ads on political campaigns

Political science professors Dave Andersen and Chris Budzisz explain how campaigns are using more and more social media and Web ads to reach supporters and potential voters, in addition to the traditional broadcast television commercials. They say sophisticated campaigns are harnessing the power of new media.- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 19

What Can I do with a Major in Political Science?

SWC students packed the Career Center to listen in on a forum describing what can be done with a major in Political Science. Four distinguished Southwestern College alumni and professionals shared their career journeys and workplace assignments. The panelists gave the current “ins and outs” of their profession and discussed their experiences. The panelists for this event included: SWC Alumna, Nora Vargas, Vice President of Community & Government Relations for Planned Parenthood & SWC Board of Trustee SWC Alumnus, Robert Montano, Attorney specializing in Criminal Defense, DUI and Estate Planning SWC Alumna, Yolanda Gabriela Apalategui Lugo, Field Representative for 40th District, California State Senator, Ben Hueso SWC Alumnus, John Williams, Graduate of SDSU’s Homeland Security Master’s Program & employed with U.S. Investigative Services, Inc.- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 1

History and Political Science at Bridgewater College

http://www.bridgewater.edu Do you want to change the future? Become a leader in policy and law? Understand the history that has shaped our world? Check out our programs in global studies, history, political science, pre-law and public policy. With four majors, three minors and four concentrations, you have numerous options to customize your degree. The history and political science department prepares you for a life of active citizenship and intellectual engagement. In your classes you’ll engage in discussion, reflection, simulations, problem-based learning and collaborative research with faculty and your fellow students. Outside the classroom you’ll have opportunities for experiential learning, such as internships and travel. You might take a leadership role in student organizations such as Student Senate and the Pre-Law Society.- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 5

Public Opinion in the Arab World: What do the latest surveys tell us?

Please join the U.S. Institute for Peace (USIP), the Arab Barometer, the Arab Reform Initiative, the Project on Middle East Democracy, and the Project on Middle East Political Science in a discussion and analysis of latest polling data from across the Middle East. learn more: http://www.usip.org/events/public-opinion-in-the-arab-world-what-do-the-latest-surveys-tell-us- published: 29 Oct 2014

- views: 0

LSE Executive Summer School – Client Testimonials

In this short film, members of the 2014 Executive Summer School cohort share their views on this executive education programme. For more information please visit www.lse.ac.uk/ess.- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 511

Diane Abbott on London: A Tale of Two Cities

Speaker: Diane Abbott MP Recorded on 22 October 2014 in CLM4.02, Clement House. The lecture will focus on the challenges facing London as a city and policy ideas to address these, chiefly the growing nature of inequality in London, the city’s growing population, the escalating housing crisis, the impact of welfare reform, and the effects of the health and social care act on public health. Additionally, the talk will seek to address the issue of powers available to City Hall in the light of the devolution question. Diane Abbott is a British Labour Party politician who has been the Member of Parliament (MP) for Hackney North and Stoke Newington since 1987, when she became the first black woman to be elected to the House of Commons. In 2010, Abbott became Shadow Public Health Minister after unsuccessfully standing for election to the leadership of the Labour Party. She tweets as @HackneyAbbott.- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 6

Rituals and Ritualism in the International Human Rights System

Speakers: Professor Hilary Charlesworth Recorded on 21 October 2014 in Wolfson Theatre, New Academic Building. This lecture will consider rituals in the international human rights system and their connection to ritualism. Hilary Charlesworth is Director of the Centre for International Governance and Justice at Australian National University and Shimizu Visiting Professor at LSE Law.- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 848

Rant video political science

Had to slow Kobe's voice down at a certain part if you didn't notice, simply because he talks way to fast.- published: 31 Oct 2014

- views: 1

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Next page »

Political science is a social science discipline concerned with the study of the state, government, and politics. Aristotle defined it as the study of the state. It deals extensively with the theory and practice of politics, and the analysis of political systems and political behavior. Political scientists "see themselves engaged in revealing the relationships underlying political events and conditions, and from these revelations they attempt to construct general principles about the way the world of politics works." Political science intersects with other fields; including anthropology, public policy, national politics, economics, international relations, comparative politics, psychology, sociology, history, law, and political theory. Although it was codified in the 19th century, when all the social sciences were established, political science has ancient roots; indeed, it originated almost 2,500 years ago with the works of Plato and Aristotle.

Political science is commonly divided into three distinct sub-disciplines which together constitute the field: political philosophy[dubious – discuss], comparative politics and international relations. Political philosophy is the reasoning for an absolute normative government, laws and similar questions and their distinctive characteristics. Comparative politics is the science of comparison and teaching of different types of constitutions, political actors, legislature and associated fields, all of them from an intrastate perspective. International relations deals with the interaction between nation-states as well as intergovernmental and transnational organizations.

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

Randall Stuart "Randy" Newman (born November 28, 1943) is an American singer-songwriter,arranger, composer, and pianist who is known for his mordant (and often satirical) pop songs and for film scores.

Newman often writes lyrics from the perspective of a character far removed from his own experiences, sometimes using the point of view of an unreliable narrator. For example, the 1972 song "Sail Away" is written as a slave trader's sales pitch to attract slaves, while the narrator of "Political Science" is a U.S. nationalist who complains of worldwide ingratitude toward America and proposes a brutally ironic final solution. One of his biggest hits, "Short People" was written from the perspective of "a lunatic" who hates short people. Since the 1980s, Newman has worked mostly as a film composer. His film scores include Ragtime, Awakenings, The Natural, Leatherheads, James and the Giant Peach, Meet the Parents, Cold Turkey, Seabiscuit and The Princess and the Frog. He has scored six Disney-Pixar films: Toy Story, A Bug's Life, Toy Story 2, Monsters, Inc., Cars and most recently Toy Story 3.

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

- Lyrics: play full screen play karaoke

- Political Science - Randy Newman

No one likes us, I don't know why

We may not be perfect but heaven knows we try

But all around, even our old friends put us down

Let's drop the big one and see what happens

We give them money but are they grateful?

No, they're spiteful and they're hateful

They don't respect us so let's surprise them

We'll drop the big one and pulverize them

Asia's crowded and Europe's too old

Africa is far too hot and Canada's too cold

And South America stole our name

Let's drop the big one, there'll be no one left to blame us

We'll save Australia

Don't wanna hurt no kangaroo

We'll build an All American amusement park there

They got surfin', too

Boom goes London and boom Paree

More room for you and more room for me

And every city the whole world round

Will just be another American town

Oh, how peaceful it will be we'll set everybody free

You'll wear a Japanese kimono and there'll be Italian shoes for me

They all hate us anyhow, so let's drop the big one now

![[u'Try 1 Political Science'][0].replace('](http://web.archive.org./web/20141111191001im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/VONf7aGgLdM/0.jpg)