- Order:

- Duration: 5:17

- Published: 2008-06-23

- Uploaded: 2011-02-26

- Author: consumerwarningnet

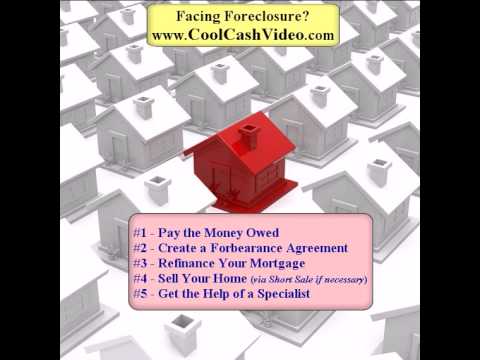

The foreclosure process as applied to residential mortgage loans is a bank or other secured creditor selling or repossessing a parcel of real property (immovable property) after the owner has failed to comply with an agreement between the lender and borrower called a "mortgage" or "deed of trust". Commonly, the violation of the mortgage is a default in payment of a promissory note, secured by a lien on the property. When the process is complete, the lender can sell the property and keep the proceeds to pay off its mortgage and any legal costs, and it is typically said that "the lender has foreclosed its mortgage or lien". If the promissory note was made with a recourse clause then if the sale does not bring enough to pay the existing balance of principal and fees the mortgagee can file a claim for a deficiency judgment.

Foreclosure by judicial sale, more commonly known as judicial foreclosure, which is available in every state (and required in many), involves the sale of the mortgaged property under the supervision of a court, with the proceeds going first to satisfy the mortgage; then other lien holders; and, finally, the mortgagor/borrower if any proceeds are left. Under this system, the lender initiates foreclosure by filing a lawsuit against the borrower. As with all other legal actions, all parties must be notified of the foreclosure, but notification requirements vary significantly from state to state. A judicial decision is announced after the exchange of pleadings at a (usually short) hearing in a state or local court. In some rather rare instances, foreclosures are filed in federal courts.

Foreclosure by power of sale, also known as nonjudicial foreclosure, is authorized by many states if a power of sale clause is included in the mortgage or if a deed of trust with such a clause was used, instead of an actual mortgage. In some states, like California, nearly all so-called mortgages are actually deeds of trust. This process involves the sale of the property by the mortgage holder without court supervision (as elaborated upon below). This process is generally much faster and cheaper than foreclosure by judicial sale. As in judicial sale, the mortgage holder and other lien holders are respectively first and second claimants to the proceeds from the sale.

Other types of foreclosure are considered minor because of their limited availability. Under strict foreclosure, which is available in a few states including Connecticut, New Hampshire and Vermont, suit is brought by the mortgagee and if successful, a court orders the defaulted mortgagor to pay the mortgage within a specified period of time. Should the mortgagor fail to do so, the mortgage holder gains the title to the property with no obligation to sell it. This type of foreclosure is generally available only when the value of the property is less than the debt ("under water"). Historically, strict foreclosure was the original method of foreclosure.

Lenders may also accelerate a loan if there is a transfer clause, obligating the mortgagor to notify the lender of any transfer, whether; a lease-option, lease-hold of 3 years or more, land contracts, agreement for deed, transfer of title or interest in the property.

The vast majority (but not all) of mortgages today have acceleration clauses. The holder of a mortgage without this clause has only two options: either to wait until all of the payments come due or convince a court to compel a sale of some parts of the property in lieu of the past due payments. Alternatively, the court may order the property sold subject to the mortgage, with the proceeds from the sale going to the payments owed the mortgage holder.

In the proceeding simply known as foreclosure (or, perhaps, distinguished as "judicial foreclosure"), the lender must sue the defaulting borrower in state court. Upon final judgment (usually summary judgment) in the lender's favor, the property is subject to auction by the county sheriff or some other officer of the court. Many states require this sort of proceeding in some or all cases of foreclosure to protect any equity the debtor may have in the property, in case the value of the debt being foreclosed on is substantially less than the market value of the immovable property (this also discourages strategic foreclosure). In this foreclosure, the sheriff then issues a deed to the winning bidder at auction. Banks and other institutional lenders may bid in the amount of the owed debt at the sale but there are a number of other factors that may influence the bid, and if no other buyers step forward the lender receives title to the immovable property in return.

In response, a slight majority of U.S. states have adopted nonjudicial foreclosure procedures in which the mortgagee, or more commonly the mortgagee's servicer's attorney or designated agent, gives the debtor a notice of default (NOD) and the mortgagee's intent to sell the immovable property in a form prescribed by state statute; the NOD in some states must also be recorded against the property. This type of foreclosure is commonly referred to as "statutory" or "nonjudicial" foreclosure, as opposed to "judicial", because the mortgagee does not need to file an actual lawsuit to initiate the foreclosure. A few states impose additional procedural requirements such as having documents stamped by a court clerk; Colorado requires the use of a county "public trustee," a government official, rather than a private trustee specializing in carrying out foreclosures. However, in most states, the only government official involved in a nonjudicial foreclosure is the county recorder.

In this "power-of-sale" type of foreclosure, if the debtor fails to cure the default, or use other lawful means (such as filing for bankruptcy to temporarily stay the foreclosure) to stop the sale, the mortgagee or its representative conduct a public auction in a manner similar to the sheriff's auction. Notably, the lender itself can bid for the property at the auction, and is the only bidder that can make a "credit bid" (a bid based on the outstanding debt itself) while all other bidders must be able to immediately present the auctioneer with cash or a cash equivalent like a cashier's check.

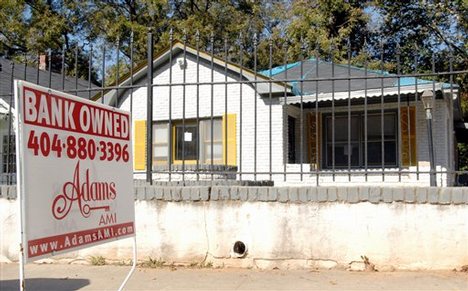

The highest bidder at the auction becomes the owner of the immovable property, free and clear of interest of the former owner, but possibly encumbered by liens superior to the foreclosed mortgage (e.g., a senior mortgage or unpaid property taxes). Further legal action, such as an eviction, may be necessary to obtain possession of the premises if the former occupant fails to voluntarily vacate.

In contrast, in nonjudicial foreclosure states like California, due process has already been judicially determined to be a frivolous defense. The entire point of nonjudicial foreclosure is that there is no state actor (i.e., a court) involved. The constitutional right of due process protects people only from violations of their civil rights by state actors, not private actors. A further rationale is that under the principle of freedom of contract, if debtors wish to enjoy the additional protection of the formalities of judicial foreclosure, it is their burden to find a lender willing to provide a traditional conventional mortgage loan instead of a deed of trust with a power of sale. The difficulty in finding such a lender in nonjudicial foreclosure states is not the state's problem. Courts have also rejected as frivolous the argument that the mere legislative act of authorizing the nonjudicial foreclosure process thereby transforms the process itself into state action.

A debtor may also challenge the validity of the debt in a claim against the bank to stop the foreclosure and sue for damages. In a foreclosure proceeding, the lender also bears the burden of proving they have standing to foreclose.

One note-worthy but legally meaningless court case questions the legality of the foreclosure practice is sometimes cited as proof of various claims regarding lending. In the case First National Bank of Montgomery vs Jerome Daly Jerome Daly claimed that the bank didn't offer a legal form of consideration because the money loaned to him was created upon signing of the loan contract. The myth reports that Daly won, and the result was that he didn't have to repay the loan, and the bank couldn't repossess his property. In fact, the "ruling" (widely referred to as the "Credit River Decision") was ruled a nullity by the courts.

In the case where the remaining mortgage balance is higher than the actual home value the foreclosing party is unlikely to attract auction bids at this price level. A house that went through a foreclosure auction and failed to attract any acceptable bids may remain the property of the owner of the mortgage. That inventory is called REO (real estate owned). In these situations the owner/servicer tries to sell it through standard real estate channels.

Nevertheless, in an illiquid real estate market or following a significant drop in real estate prices, it may happen that the property being foreclosed is sold for less than the remaining balance on the primary mortgage loan, and there may be no insurance to cover the loss. In this case, the court overseeing the foreclosure process may enter a deficiency judgment against the mortgagor. Deficiency judgments can be used to place a lien on the borrower's other property that obligates the mortgagor to repay the difference. It gives lender a legal right to collect the remainder of debt out of mortgagor's other assets (if any).

There are exceptions to this rule, however. If the mortgage is a non-recourse debt (which is often the case with owner-occupied residential mortgages in the U.S.), lender may not go after borrower's assets to recoup his losses. Lender's ability to pursue deficiency judgment may be restricted by state laws. In California and some other states, original mortgages (the ones taken out at the time of purchase) are typically non-recourse loans; however, refinanced loans and home equity lines of credit aren't.

If the lender chooses not to pursue deficiency judgment—or can't because the mortgage is non-recourse—and writes off the loss, the borrower may have to pay income taxes on the unrepaid amount if it can be considered "forgiven debt." However, recent changes in tax laws may change the way these amounts are reported.

Any liens resulting from other loans taken out against the property being foreclosed (second mortgages, HELOCs) are "wiped out" by foreclosure, but the borrower is still obligated to pay those loans off if they are not paid out of the foreclosure auction's proceeds.

* Neighborhood Strategies for Addressing Foreclosure.

* The "First Amended Complaint" filed by the state of California against Countrywide Mortgage for those who had Countrywide mortgages and had been foreclosed, or would be foreclosed or at risk of foreclosure.

* The stipulated judgment against Countrywide and in favor of the state of California for those who had Countrywide mortgages and had been foreclosed, or would be foreclosed or at risk of foreclosure.

Category:Real property law Category:Mortgage Category:Personal financial problems Category:United States housing bubble

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.