San Francisco may be one of America’s most iconic cities that draws thousands of tourists and transplants every year, but there’s one neighborhood in town that virtually everyone prefers to avoid: the Tenderloin. As a freelance writer concerned about this country’s growing socio-economic inequality, however, I decided to head into an area VICE has described as “the most hellish neighborhood in San Francisco” to see what I could learn for myself. The New York Times, for what its worth, refers to the Tenderloin as “ragged, druggy and determinedly dingy.” As I approached the Tenderloin, I asked a man familiar with the area how to reach the neighborhood’s most infamous corner—Turk & Taylor—and he looked at me like I had three heads. “What business you got on Turk & Taylor?,” the man asked, taken aback that a young white man carrying a $2,000 camera would be interested in going there in the first place.

“Photography,” I responded.

As you can see from some of my images, much of what I observed in the Tenderloin is consistent with what you may have heard. First and foremost is the widespread, heart-breaking poverty. Spend just a few minutes in the Tenderloin and you will see people rummaging through trashcans looking for a meal, sleeping on sidewalks hoping for a dream, and smoking from pipes reaching for an escape. There are people with bloodstained jeans milling about, aimlessly mumbling to themselves that they “cannot deal with these fucking extraterrestrials today.” The police questioned a man right in front of me as I walked around; the man sat cross-kneed on the ground handcuffed, and down his chin ran a small trail of blood. At one point, just a few feet from me, I saw for the first time in my life that most devastating of drugs: heroin. The man holding it tied a belt around his arm, quickly scanned his surroundings, and pressed the syringe deep into his vein.

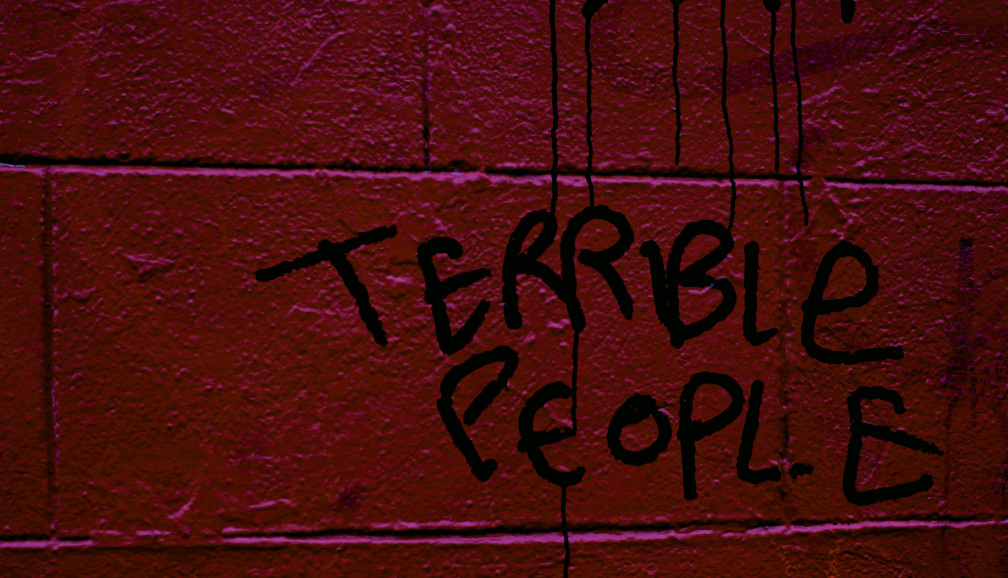

On the other side of all this, however, is a part of the Tenderloin that is bursting with color, life, and hope. Few people seem to talk about this part of the Tenderloin. You’ll see from the images below that the Tenderloin is home to a wide array of intricate graffiti and street art, each more impressive than the next. Nearly every block had a detailed piece to observe, and the artwork covered a wide range of themes, from idealized versions of the neighborhood to devastating portrayals of a life beset by poverty.

I encourage readers to visit the Tenderloin the next time you find yourself in San Francisco. While the neighborhood does have a high crime rate and one should exercise caution, I had absolutely no issues roaming the neighborhood alone for hours—while carrying my camera, iPhone, and computer—during the day. Those seeking to learn more about the Tenderloin should read this article from KQED. I hope you enjoy my photographs, and thank you for reading.

Find me on Twitter @4thEstateWatch.