Michael Schmidt is an investigative journalist, an anarchist theorist and a radical historian based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He has been an active participant in the international anarchist milieu, including the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front. His major works include ‘Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism (2013, AK Press) and, with Lucien van der Walt, ‘Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism’ (2009, AK Press).

In your recent book, Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism (AK Press, USA, 2013), you argue that anarchists have often failed to draw insights from anarchist movements outside of Western Europe. What lessons does the global history of anarchism have to offer those engaged in struggle today?

The historical record shows that anarchism’s primary mass- organisational strategy, syndicalism, is a remarkably coherent and universalist set of theories and practices, despite the movement’s grappling with a diverse set of circumstances. From the establishment of the first non-white unions in South Africa and the first unions in China, through to the resistance to fascism in Europe and Latin America – the establishment of practical anarchist control of cities and regions, sometimes ephemeral, sometimes longer lived in countries as diverse as Macedonia (1903), Mexico (1911, 1915), Italy (1914, 1920), Portugal (1918), Brazil (1918), Argentina (1919, 1922), arguably Nicaragua (1927-1932), Ukraine (1917-1921), Manchuria (1929-1931), Paraguay (1931), and Spain (1873/4, 1909, 1917, 1932/3, and 1936-1939).

The results of the historically-revealed universalism are vitally important to any holistic understanding of anarchism/syndicalism:

Firstly, that the movement arose in the trade unions of the First International, simultaneously in Mexico, Spain, Uruguay, and Egypt from 1868-1872 (in other words, it arose internationally, on four continents, and was explicitly not the imposition of a European ideology);

Secondly, there is no such thing within the movement as “Third World,” “Global Southern” or “Non-Western” anarchism, that is in any core sense distinct from that in the “Global North”. Rather that they are all of a feather; the movement was infinitely more dominant in most of Latin America than in most of Europe. The movement today is often more similar in strength to the historical movements in Vietnam, Lebanon, India, Mozambique, Nigeria, Costa Rica, and Panama – so to look to these movements as the “centre” of the ideology produces gross distortions.

The lessons for anarchists and syndicalist from “the Rest” for “the West” can actually be summed up by saying that the movement always was and remains coherent because of its engagements with the abuse of power at all levels.

How is anarchism still relevant in the world today? What do anarchist ideas about strategy and tactics have to offer people active in social movements today?

I’d say there are several ways in which anarchism is relevant today:

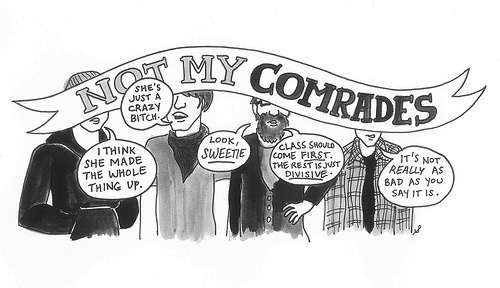

1) It provides the most comprehensive intersectoral critique of not just capital and the state; but all forms of domination and exploitation relating to class, gender, race, colour, ethnicity, creed, ability, sexuality and so forth, implacably confronting grand public enemies such as war-mongering imperialism and intimate ones such as patriarchy. It is not the only ideology to do this, but is certainly the main consistently freethinking socialist approach to such matters.

2) With 15 decades of militant action behind it, it provides a toolkit of tried-and proven tactics for resistance in the direst of circumstances, and, has often risen above those circumstances to decentralise power to the people. These tactics include oppressed class self-management, direct democracy, equality, mutual aid, and a range of methods based in the conception that the means we use to resist determine the nature of our outcomes. The global anti-capitalist movement of today is heavily indebted to anarchist ethics and tactics for its internal democracy, flexibility, and its humanity.

3) Strategically, we see these tactics as rooted in direct democracy, equality, and horizontal confederalism (today called the “network of networks”), in particular in the submission of specific (self-constituted) anarchist organisations to the oversight of their communities, which then engage in collective decision-making that is consultative and responsible to those communities. It was the local District Committees, Cultural Centres, Consumer Co-operatives, Modern Schools, and Prisoner-support Groups during the Spanish Revolution that linked the great CNT union confederation and its Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) allies to the communities they worked within: the militia that fought on the frontlines against fascism, and the unions that produced all social wealth would have been rudderless and anchorless without this crucial social layer to give them grounding and direction. In order to have a social revolution of human scale, we submit our actions to the real live humans of the society that we work within: this is our vision of “socialism”.

In sum, anarchism’s “leaderless resistance” is about the ideas and practices that offer communities tools for achieving their freedom, and not about dominating that resistance. Anarchists ideally are fighting for a free world, not an anarchist world, one in which even conservatives will be freed of their statist, capitalist and social bondage to discover new ways of living in community with the rest of us.

Is it important to advance anarchism explicitly? Or is it enough to engage in social movements whose objectives we support without adopting the anarchist label?

This is primarily a tactical question, because the approaches adopted by anarchists have to be suited to the objective conditions of the oppressed classes in the area in which they are active, and the specific local cultures, histories, even prejudices of those they work alongside. The proper meaning of “anarchist” as a democratic practice – a practical, not utopian, one at that – of the oppressed classes clearly needs to be rehabilitated in Australia and New Zealand. Just as the Bulgarian syndicalists who built unions in the rural areas relied upon ancient peasant traditions of mutual aid to locate syndicalist mutual aid within an approachable framework, so you too must find a good match for anarchism within your cultures. We, for example, have relied heavily on traditional township forms of resistance to explain solidarity, mutual aid, egalitarianism, and self-management. Yet, it is also a strategic question because in my opinion, where you have the bourgeois-democratic freedoms to organise openly and without severe repression, it is important to form an explicitly anarchist organisation in order to act as:

a) a pole around which libertarian socialists, broadly speaking, can orbit and to which they can gravitate organisationally – though it is important to recognise that there can be more than one such pole; and

b) as a lodestar of clear, directly-democratic practice, offering those who seek guidance a vibrant toolkit of time-tested practices with which to defend the autonomy of the oppressed classes from those who would exploit/oppress them.

It is the question of responsibility that compels us to nail our colours to the mast. This is for three reasons:

a) firstly, because we are not terrorists or criminals and we have nothing to be ashamed about that requires hiding, even from our enemies (we should be able to openly defend our democratic credentials before mainstream politicians);

b) secondly, that by forming a formal organisation, people we interact with are made aware that none of us are loose cannons but are subject to the mandates of our organisation (with those mandates being public, fair and explicit); and

c) lastly, but most importantly, that the communities we work within, whether territorial (townships, cities, etc), or communities of interest (unions, queer rights bodies, residents’ associations etc) know that we are responsible to them, that our actions, positions and strategies are consultative, collaborative, responsive and responsible to those they may most immediately affect.

We’ve been eagerly awaiting the release of Counter Power Volume 2, Global Fire: 150 Fighting Years of Revolutionary Anarchism, is there any news on when it will be released? What ground will you be covering that people might not expect?

Global Fire is really a monstrous work: in research and writing for close to 15 years now, it’s really an international organised labour history over 150 years, tracing the organisational and ideological lineages of anarchism/syndicalism in all parts of the world. We have a lot to get right: we need to have a theory, at least, for why the French syndicalist movement turned reformist during World War I, or why the German revolutionary movement as a whole, both Marxist and anarchist, collapsed over 1919-1923, paving the way for the Nazis. These are issues of intense argument among historians, and we have to be able to back up with sound argument our stance in every case, from the well-known, like the Palmer Raids against the IWW in the USA in the wake of World War I, to the fate of syndicalism in Southern Rhodesia in the 1950s, or of the near-seizure of power in Chile by the syndicalists in 1956, and their fate under the red regimes in Cuba, Bulgaria and China, or the white regimes in Chile, South Korea, or Argentina. We need to understand the vectors of the anarchist idea in a holistic, transnational sense, but have often been hampered by the narrowness of national(ist) perspectives. Even within the Anarchist movement, histories have been more anecdotal and partisan than truly balanced and rigorous assessments, and have often been very disarticulated by language differences. With lengthy delays incurred by us trying to make sure that Global Fire is the best (in fact only) holistic international account of the movement. You can be assured that Lucien is working on refining the text, which if published in its current format would weigh in at a whopping 1,000 pages, and that we have a pencilled-in release date for 2015, though perhaps 2016 is more realisable.